This essay was written on 01 October 2023, and is linked to the Joint Operations Planning Module at Australian Command and Staff College

The Chief of Staff (CoS) convenes a wargame, and the organisation’s best planners are involved. Everything goes smoothly, and decisions are made based on what the CoS and more senior planners suggest. Suddenly, the plan catastrophically fails. Why did this happen? How could it have been avoided? What other tools were available that the staff failed to employ?

Introduction

The Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) is the ADF’s primary joint planning and decision-making tool, aiming to provide guidance for planning campaigns and operations.[1] This publication is uniquely Australian, designed for ADF staff and planning functions; however, coalition interoperability requirements determine that it mirrors the planning process of the United Kingdom, the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) joint operational planning doctrine.[2] However, there is a clear observable difference in step four of the JMAP (Course of Action Analysis, or COA-A), which guides the conduct of a wargame. While the UK, US, and NATO operational planning doctrine promote the benefits of red teaming and Alternative Analysis (AltA) techniques to support the achievement of this step, this point is notably absent from the Australian Defence Force Procedures (ADFP) 5.0.1—Joint Military Appreciation Process. According to the ADFP 5.0.1, a wargame aims to expose flaws in the friendly COA when pitched against an adversary COA, with the output as a refined and improved friendly COA.[3] This definition makes sense, and a well-executed wargame will generally facilitate meaningful analysis of selected COAs. However, the critical question remains: could our analysis be stronger?

This paper will argue that the ADFP 5.0.1’s omission of options to enhance planning outcomes through red teaming and AltA techniques is an inherent weakness, stifling opportunities for applied critical thinking and reducing the veracity of COA-A. Part 1 will begin by unpacking the concepts of red teaming and AltA, highlighting their utility alongside wargaming before explaining how and why the US, the UK, and NATO planning doctrine incorporates these techniques within the planning process. Part 2 considers why red teaming and AltA should be promoted within the JMAP. In doing so, this paper will argue that non-linear and applied critical thinking, the ability to challenge organisational thinking, and incorporating red teaming to deal with complexity lead to better results. Part 3 will then provide options for the ADF: recommending that a greater explanation of red teaming and AltA be included as a section within the ADFP 5.0.1, alternatively, by publishing a standalone ADF Red Teaming Handbook. This paper does not suggest that these techniques should replace wargaming. Instead, their utility extends across the entire planning process but with a focus on COA-A outcomes. A wargame is time- and resource-intensive, requiring considerable preparation and placing demands on key planning staff. Red teaming and AltA provide a range of simple techniques to improve decision making and identify key risks. Planning staff always work hard, so how about working smarter?

What is red teaming, who uses it and why?

The concepts of red teaming and AltA, processes by which we critically and independently examine our plans and ideas, remain undervalued within the ADF joint planning doctrine. If formally embraced, as it has been by many of our partners, it would enhance decision making, objective consideration of ‘what ifs’, and improve how we mitigate risks.[4] Often thought of as simply ‘thinking like the enemy’, its contemporary application is much greater. Simple techniques such as ‘assessment of alternative futures’, playing ‘devil’s advocate’ and ‘challenging assumptions’ also aid in hedging against planning staff inexperience.[5] Red teaming and AltA do this by challenging groupthink and commonly accepted solutions by combatting the old axiom ‘this is how it’s always been done’.[6] Furthermore, it is a concept that others have widely embraced, including the National American Space Agency (NASA), the US military, the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), and NATO.[7] Although the ADF has been slow on the uptake, the approaches taken by other military organisations highlight a range of options the ADF could adopt to strengthen the ADFP 5.0.1 and enhance planning outcomes.

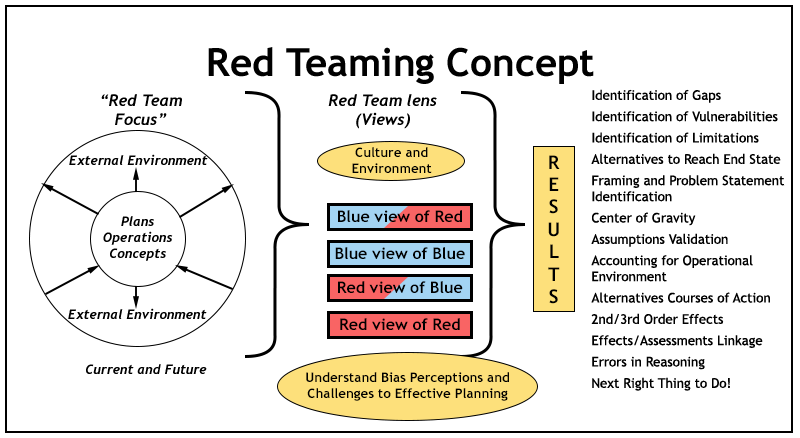

Figure 1 – The US Military Red Teaming Concept.[8]

US Doctrinal Approach

Throughout the operations planning process, the US military places a high premium on applied critical thinking skills, and red teaming uses structured tools and techniques to assist in this approach. The US Army Red Team Handbook defines red teaming as an “adaptable approach to thinking and planning that is altered to suit the situation.”[9] Furthermore, red teaming uses structured techniques to help us ask better questions, challenge assumptions, expose flaws we might otherwise have missed, and develop alternatives we might not have known existed.[10] Aligned with this definition, applied critical thinking is the deliberate application of these tools and techniques to review our plans by ‘asking better questions’.[11] The US military uses the Military Decision-Making Process (MDMP), a process closely aligned with the JMAP.[12] Notably, US doctrine highlights that red teaming techniques have broad applicability across the entire span of operational planning. By contrast, the ADF Philosophical Doctrine (ADFP-5 Planning ed 1) does refer to red teaming in its explanation of COA-A, albeit in a single statement. It states that COA-A ‘may also employ a range of tools and methods known as red team methodologies’.[13] However, it goes no further. Through footnotes, it refers the reader to the US Army Red Team Handbook.[14] This contrast highlights that although the MDMP and JMAP involve similar steps, the US doctrine takes a more flexible approach to its application of the planning process by using additional tools or techniques to enhance planning outcomes.

UK/NATO Doctrinal Approach

The UK planning doctrine, recently aligned to that of NATO doctrine, provides another example of how the ADF could promote red teaming and AltA within our planning doctrine.[15] By proactively encouraging red teaming and AltA techniques, UK doctrine incorporates a broader, more flexible approach to wargaming than the ADFP 5.0.1. Like the US approach, the UK does this through their separate but closely linked Wargaming Handbook and Red Teaming Handbook.[16] The Wargaming Handbook points out that no single, commonly accepted definition of wargaming exists and that better results are achieved using a definition more closely aligned to red teaming.[17] Moreover, the UK Wargaming Handbook outlines the limitations of wargaming, stating that wargames are only as good as the participants and are not sufficiently predictive. It further highlights that red teaming is a closely associated technique that does not replace wargaming. These flexible and adaptable critical thinking techniques allow the end user (usually the commander) to make better-informed decisions.[18] Finally, wargaming must be considered a recognised red teaming tool, not the other way around. While red teams often support war games, neither is less critical, and the conduct of wargaming alongside select red teaming techniques should be considered an opportunity to mitigate the inherent weaknesses of both approaches. These important distinctions are not mentioned within the ADF planning doctrine, not even within the ADFP 5.0.1, where it would be most beneficial. The NATO Alternative Analysis Handbook

In contrast with the US and the UK doctrine, NATO has developed a similar approach to red teaming called AltA, and while the techniques are the same, the definition differs slightly. NATO doctrine defines AltA as ‘the deliberate application of independent, critical thought and alternative perspective to improve decision making’.[19] The key differences between this definition and the definition offered by red teaming are as follows. Firstly, ‘independent’ refers to a condition free from control or influence by others in matters of thinking and belief.[20] This point is important because setting staff aside to work independently of groupthink and bias remains critical during COA-A. Secondly, the ‘alternative perspective’ provides the frame of reference. An alternative perspective comes from looking at facts, problems or situations through a different mindset, belief or value structure.[21] The NATO AltA Handbook reinforces that an alternative perspective allows planners to observe and thus manage ingrained bias. However, this is not the approach taken within ADFP 5.0.1, which focuses exclusively on the conduct of the wargame where ‘rules’ are established, suggesting participants maintain impartiality.[22] This approach highlights that ADFP 5.0.1 demonstrates a reactive rather than proactive approach to managing biases. In contrast, the NATO approach aims to actively manage bias through techniques that enable independent, alternate perspectives, citing clear explanations and examples of how staff can use alternative techniques to strengthen wargaming outcomes. While red teaming and AltA are similar, the ADFP 5.0.1 considers neither in supporting the planning process.

Why should red teaming be incorporated into the ADF Planning Doctrine?

Promoting critical and non-linear thinking

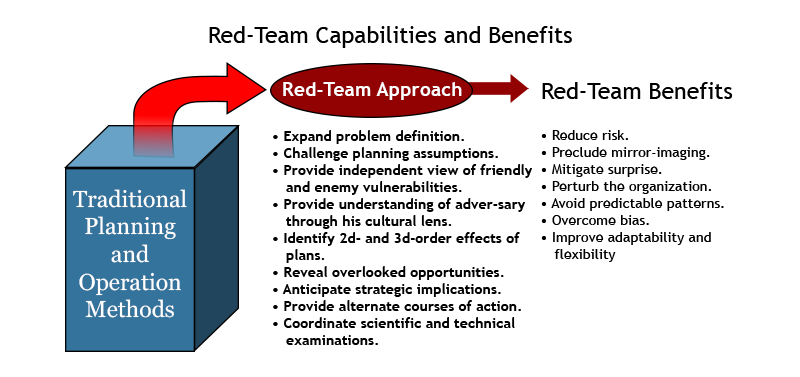

As the operating environment becomes more complex due to factors including new technology, grey zone operations and a tendency towards asymmetric warfare, there remain three sound reasons why the ADF should proactively promote red teaming and AltA during operational planning.[23] The first reason is that these techniques actively promote critical and non-linear thinking. Since its inception, linear thinking has underpinned the basic conceptualisation of the application of military power for the ADF.[24] The ADFP 5.0.1 acknowledges this, highlighting that although the world is ‘non-linear, fluid and complex’,[25] linear thinking is inevitable owing to the requirement to start somewhere, finish somewhere and progress in a broadly structured fashion.[26] Because of the JMAPs’ linearity, COAs are only as good as when the initial scoping and framing step was conducted, right back at step one. Therefore, an inherent weakness of the JMAP is that COAs brought forward to wargaming in step four may not be adequately suited to changes occurring since planning was initiated.[27] Red teaming can address these shortfalls through structured tools and techniques that offset the linear process and facilitate applied critical thinking. In practice, these techniques help planners identify biases, additional assumptions, and instances of cognitive autopilot. The outcome is that analysing group perceptions and interpretations leads to better decisions.[28] Finally, red teaming allows us to explore alternatives, revealing unseen options that could enhance our freedom of manoeuvre.

Figure 2 – Capabilities and Benefits of Red Teaming.[29]

In accepting that the JMAP is inherently linear, planning staff must also address this limitation at the grassroots level, where ADF members begin training on the JMAP. JMAP proponents often respond to this criticism by suggesting that the JMAP is only linear for beginners.[30] The ADFP 5.0.1, however, omits this disclaimer, and aiming for linearity is insufficient for three reasons. Firstly, marginal benefits gained by beginners for adhering to a strictly linear step-by-step checklist undermine the flexibility of how the JMAP should be applied. For this reason alone, why not educate beginners on the utility of red teaming and AltA techniques when learning the JMAP for the first time? Secondly, teaching fledging planners to aim for linearity is to teach them poorly, especially if this is not the doctrine’s intent.[31] It is often incorrectly assumed that beginners become experts when moving from the tactical to the operational level as complexity and outputs increase. This view could not be further from the truth. Commander-imposed deadlines often mean these ‘experts’ revert to the step-by-step process without considering other available tools, and planners are unlikely to visit red teaming techniques unless prompted to do so. Thirdly and most importantly, nothing precludes the use of additional checklists, handbooks or aide memoirs.[32] The ADF should not have to revert to foreign doctrine while learning our own. The ADFP 5.0.1 could be improved by including a section that promotes red teaming and AltA techniques or vectoring the planner onto a readily accessible ADF-commissioned handbook.

Challenge the organisation’s thinking

The second reason for ADF doctrine to promote red teaming and AltA is that it allows planners to challenge the organisation’s thinking. To allow planning to progress, planners often make assumptions where gaps in knowledge or understanding exist.[33] Assumptions are information accepted as truth in the absence of fact, and they come in two forms. Explicit assumptions are those clearly stated. Conversely, implicit assumptions usually include statements such as ‘experience has shown,’ ‘generally’ and ‘typically’.[34] However, a phenomenon often occurs here called ‘retrievability bias’, where the ‘frequency of similar events in our past reinforces preconceived notions of comparable situations occurring in the future’.[35] Red teaming offsets this ingrained organisational thinking by challenging preconceived ideas or assumptions when everyone is thinking similarly. Most importantly, assumptions contribute to the planner’s model of reality. While the ADFP 5.0.1 refers to ‘assumptions’ 62 times, it focuses on their ‘identification’ and ‘listing’ rather than assessing their validity and how they may/may not impact the operational environment or the plan as it evolves.[36]

The UK Red Teaming Handbook offers a simple technique to assist: the assumptions check. The technique is intuitive and contains only four steps.[37] Step 1: write a short narrative of the situation or problem (which will likely contain assumptions). Step 2: analyse the narrative and determine which are explicit (clearly started). Step 3: highlight those that are implicit, and Step 4: ask two questions for each of those highlighted: Is this assumption still valid? Moreover, how does this change the plan if it is invalid?[38] This technique can be conducted at every step of the JMAP and takes little time to complete. An inherent weakness of the ADFP 5.0.1 is its focus on identification and listing rather than validating and assessing the impact of assumptions. As the operational environment evolves during planning, this technique ensures that assumptions based on past experience remain applicable to the current situation or problem.

Dealing with complexity

The third reason ADF doctrine should promote red teaming and AltA during planning is that it assists with processing and reducing complexity. Planning staff often face complicated tasks, and complexity increases as we move from the tactical to the operational level of planning. In many instances, not only is the solution to a problem but the problem itself and its surrounding context uncertain.[39] Moreover, planning staff often lack experience, and the posting cycle within the ADF means that people generally move into new roles after 1-2 years. This cycle limits the ability of individuals and teams to become experts in the process. To combat these challenges, red teaming and AltA techniques provide an initial starting point for a task or complex problem, exploring the context through different techniques and generating ideas to tackle the problem.[40] Behavioural psychologist Dietrich Doerner supports the argument that experience is essential.[41] In 1996, studying how people interact with complex problems, Doerner discovered that ‘experience’ was the most critical variable in distinguishing performance in simulations involving complexity.[42] Therefore, in place of experience, red teaming techniques support planners in generating better outcomes for complex problems, particularly when incorporated early in the planning process. The contemporary operating environment presents planners with increasing complexity, and expanding the ADF planning doctrine to include red teaming and AltA techniques is a proven way to address this.[43] While opening the aperture may be daunting for some, planners should not avoid using additional techniques to challenge solutions, actively explore them and highlight opportunities we otherwise did not know existed.

Options available for the ADF

Two options exist for the ADF to incorporate red teaming and AltA techniques into the JMAP doctrine. The first is by including a section within ADFP 5.0.1 Chapter One – Joint Planning. This section would provide an overview and clear explanation of red teaming and AltA as tools and techniques to enhance the joint planning process and, more importantly, where to find them within foreign doctrine. Stating this upfront would provide a foundation for its use in subsequent steps, emphasising its utility in offsetting inherent weaknesses of the JMAP with its deliberately structured and inherently linear progression. The UK has adopted this approach, with Chapter 3 of the AJP-5 including a page on how red teaming can assist with ‘challenging the orthodoxy’ of groupthink and bias before referring the reader to the UK Red Teaming Handbook.[44] Furthermore, an enhancement to this option would be explicitly referencing additional analysis tools such as ‘premortem’ and ‘devil’s advocate’ during step four, COA-A. While notably absent from the ADFP 5.0.1, the UK and US planning doctrine reiterates the utility of such techniques during COA-A before redirecting planners to their respective national handbooks.[45]

The second option available to the ADF builds on option one but with the creation of an ‘ADF Red Teaming Handbook’. As the author experienced during wargaming serials of the Joint Operations Planning module at the Australian Command and Staff College, the requirement to leverage foreign planning doctrine to supplement the ADF doctrine presented a unique oddity that was hardly intuitive. Creating an ADF Red Teaming Handbook would be straightforward, modelled on one of the foreign variants discussed or taking the best elements from each. In addition to the option for inclusion within ADF doctrine, red teaming as a concept, its utility, and some of the more commonly applicable techniques should be taught to beginners learning the JMAP for the first time. Techniques including ‘premortem analysis’, Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis, and ‘devil’s advocate’ are simple to teach, intuitive to learn and promote critical thinking in a non-linear fashion.[46] These skills are equally important for beginners as they are for more experienced planners at the operational level. After all, despite what we know about human behavioural psychology, decision making remains a natural and often intuitive process with no definable process,[47] and red teaming complements the JMAP by offsetting the formulaic approach inherent within the steps.

Conclusion

The above analysis highlights that by contrast with the UK, US and NATO planning doctrine, red teaming and AltA remain severely undervalued by the ADF. The concept of red teaming and its associated techniques have long been embraced by many highly successful organisations, all of whom deal with planning in complexity. While subtly different in their approach, the US, UK and NATO publications highlight the complementary utility of red teaming and AltA alongside the traditional, linear, step-by-step military planning process. As shown above, three core reasons underpin this. Red teaming actively promotes critical and non-linear thinking, an inherent and accepted limitation of the JMAP. For this reason alone and particularly relevant for the inexperienced planner, red teaming techniques should be taught alongside the JMAP at the grassroots level. Secondly, red teaming allows us to challenge the organisation’s thinking. By combatting ‘retrievability bias’—a natural phenomenon by which planners often rely on previous experience to deal with new and novel problems—red teaming allows planners to ask better questions and assess the validity and impact of assumptions.

Thirdly and most importantly, red teaming helps to deal with complexity. With contemporary trends in warfare resulting in a more complex operating environment, red teaming and AltA offset planning staff inexperience by providing an initial starting point or alternate lens to break down the problem. Lastly, the ADF is lagging behind its partners and allies; two options exist to correct this. The first is an amendment to the ADFP 5.0.1 to include a red teaming section within Chapter 1 – Joint Planning. In addition, Chapter 4 (COA-A) could offer red teaming techniques alongside examples to enhance this option. The second option is to develop a standalone ADF Red Teaming Handbook, the approach taken by the US, UK and NATO. The ADF planning mentality must continue to evolve as war is a complex, ever-changing system. Joint planners increasingly require techniques such as red teaming to challenge solutions, explore different outcomes, highlight opportunities and reduce operational risk.

‘Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations.’ 2019, accessed July, 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/971390/20210310-AJP_5_with_UK_elem_final_web.pdf.

ADF. Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1: Plans Series: Joint Military Appreciation Process. Canberra: Directorate of Information, Graphics and eResources, Lessons and Doctrine Directorate, 2019.

United States Army. ADP 5-0: The Operations Process, 2019.

Ministry of Defence (MoD). AJP-5 Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations, 2019.

———. Wargaming Handbook, 2017.

Cancian, Matthew. ‘Red Team: How to Succeed by Thinking Like the Enemy.’ 2017, 127. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgao&AN=edsgcl.491086352&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Constantinianu, Silviu. ‘Red Team - Critical Thinking Main Tool in the Operations Planning Process.’ Article. Romanian Military Thinking, no. 1 (01// 2020): 122-35. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=tsh&AN=141836953&site=eds-live&custid=s3330841.

Dietrich, Doerner. ‘The Logic of Failure: Recognising and Avoiding Error in Complex Situations. English translation. Metropolitan Books (1996).

Dietrich, Doerner. Metropolitan Books, and Henry Holt. ‘The Logic of Failure: Why Things Go Wrong and What We Can Do to Make Them Right.’ FACILITATION: AResearch & APPLICATIONS (2001): 86.

Fontenot, Gregory. ‘Seeing Red: Creating a Red-Team Capability for the Blue Force.’ Article. Military Review 85, no. 5 (09//Sep/Oct2005 2005): 4-8. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=tsh&AN=19663156&site=eds-live&custid=s3330841.

Australian Defence Force. ADF Philosophical Doctrine: Planning, 2022.

Hoffman, Bryce G. Red Teaming: Transform Your Business by Thinking Like the Enemy. Hachette UK, 2017.

Jackson, Aaron P. ‘A Tale of Two Designs: Developing the Australian Defence Force’s Latest Iteration of Its Joint Operations Planning Doctrine.’ Journal of Military and Strategic Studies 17, no. 4 (2017).

Lauder, Matthew. ‘Red Dawn: The Emergence of a Red Teaming Capability in the Canadian Forces.’ Canadian Army Journal 12, no. 2 (2009): 25-36.

Longbine, David F. ‘Red Teaming: Past and Present.’ School of Advanced Military Studies, Army Command and General Staff College (2008).

Maher, Andrew. ‘Strategic Planners: A Response to Operational Complexity.’ [In English]. Journal Article. Australian Army Journal 13, no. 1 (2016): 81-100. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.663648981528906.

MoD, UK. The Red Teaming Handbook, 2021.

NATO. ‘The NATO Alternative Analysis Handbook.’ 2017. https://www.act.nato.int/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/alta-handbook.pdf.

Post, Ryan. ‘The Joint Military Appreciation Process: The Good, the Bad and Some Alternatives.’ The Forge (2022). https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2022/joint-military-appreciation-process-good-bad-and-some-alternatives.

Rose, Nick. ‘Thinking Red for the Australian Army.’ Land Power Forum (2014). http://www.army.gov.au/Our-future/Blog/2014/September/Thinking-Red-for-the-Australian-Army.

Scott, SM. ‘The ADF Needs Non-Linearity in Contemporary Planning.’ The Forge, 2022. https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2022/adf-needs-non-linearity-contemporary-planning.

TRADOC G-2, US Army. The Red Team Handbook: The Army’s Guide to Making Better Decisions: University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies.

Trammell, Aaron. ‘Red Team: How to Succeed by Thinking Like the Enemy.’ Political Psychology 40, no. 4 (08/01/2019): 905-09. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edswss&AN=000475645100015&site=eds-live&scope=site.

University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies. Red Team Handbook. 2011. https://newandimproved.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/ufmcs_red_team_handbook_apr2011.pdf.

Walker, David L. ‘Refining the Military Appreciation Process for Adaptive Campaigning.’ Australian Army Journal 8, no. No 2 (2011). https://researchcentre.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/aaj_2011_2.pdf.

Williams, Blair S. ‘Heuristics and Biases in Military Decision Making.’ Article. Military Review 90, no. 5 (09//Sep/Oct2010 2010): 40-52. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=tsh&AN=55382589&site=eds-live&custid=s3330841.

Zweibelson, Ben. ‘An Awkward Tango: Pairing Traditional Military Planning to Design and Why It Currently Fails to Work.’ Article. Journal of Military & Strategic Studies 16, no. 1 (03// 2015): 11-41. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=tsh&AN=101794119&site=eds-live&custid=s3330841.

1 ADF, Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1: Plans Series: Joint Military Appreciation Process, (Canberra: Directorate of Information, Graphics and eResources, Lessons and Doctrine Directorate, 2019). p iii

2 Umang Nautiyal, "The Frameworks Are Fine, They Just Need a Reboot," The Forge (2021)https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2021/frameworks-are-fine-they-just-need-reboot

3 ADF. Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1: Plans Series: Joint Military Appreciation Process. 5-3

4 Nick Rose, "Thinking Red for the Australian Army," Land Power Forum (2014), http://www.army.gov.au/Our-future/Blog/2014/September/Thinking-Red-for-the-Australian-Army.

5 UK MOD, The Red Teaming Handbook, (2021).

6 Rose, "Thinking Red for the Australian Army."

7 Rose, "Thinking Red for the Australian Army."

8 University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies. Red Team Handbook. 2011. https://newandimproved.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/ufmcs_red_team_handbook_apr2011.pdf . p 9

9 US Army TRADOC G-2, The Red Team Handbook: The Army's guide to making better decisions, (University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies). p 3

10 TRADOC G-2, Short The Red Team Handbook: The Army's guide to making better decisions. p 3

11 TRADOC G-2, Short The Red Team Handbook: The Army's guide to making better decisions. p 44

12 Army, US. ADP 5-0: The Operations Process, 2019.

13 Australian Defence Force, ADF Philosophical Doctrine: Planning, (2022). p 78

14 Force, Short ADF Philosophical Doctrine: Planning. p 63

15 "Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations," 2019, accessed July, 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/971390/20210310-AJP_5_with_UK_elem_final_web.pdf. p vii

16 Ministry of Defence, Wargaming Handbook, (2017).

MOD, Short. The Red Teaming Handbook.

17 Defence, Short. Wargaming Handbook. p 5

18 Defence, Short. Wargaming Handbook. p 13-14

19 NATO, "The NATO Alternative Analysis Handbook," (2017). https://www.act.nato.int/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/alta-handbook.pdf. p 3

20 NATO, "The NATO Alternative Analysis Handbook." p 3

21 NATO, "The NATO Alternative Analysis Handbook." p 3-4

22 ADF, Short. Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1: Plans Series: Joint Military Appreciation Process. p 4-9

23 David F Longbine, "Red teaming: past and present," School of Advanced Military Studies, Army Command and General Staff College (2008). p iii

24 SM Scott, "The ADF needs non-linearity in contemporary planning" (The Forge, 2022). https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2022/adf-needs-non-linearity-contemporary-planning.

25 ADF, Short Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1: Plans Series: Joint Military Appreciation Process. p 1-9

26 ADF, Short Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1: Plans Series: Joint Military Appreciation Process. p 1-9

27 Ryan Post, "The Joint Military Appreciation Process: The Good, The Bad and Some Alternatives," The Forge (2022), https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2022/joint-military-appreciation-process-good-bad-and-some-alternatives.

28 TRADOC G-2, Short The Red Team Handbook: The Army's guide to making better decisions. p 49

29 Gregory Fontenot, "Seeing Red: Creating a Red-Team Capability for the Blue Force," Article, Military Review 85, no. 5 (09//Sep/Oct2005 2005), https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=tsh&AN=19663156&site=eds-live&custid=s3330841. p 5

30 David L Walker, "Refining the Military Appreciation Process for adaptive campaigning," Australian Army Journal 8, no. no 2 (2011), https://researchcentre.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/aaj_2011_2.pdf. p 87

31 Walker, "Refining the Military Appreciation Process for adaptive campaigning."p 88

32 Walker, "Refining the Military Appreciation Process for adaptive campaigning."p 88-89

33 Longbine, "Red teaming: past and present."p 8

34 MOD, Short The Red Teaming Handbook. p 41

35 Blair S. Williams, "Heuristics and Biases in Military Decision Making," Article, Military Review 90, no. 5 (09//Sep/Oct2010 2010), https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=tsh&AN=55382589&site=eds-live&custid=s3330841. p 42

36 ADF, Short Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1: Plans Series: Joint Military Appreciation Process.

37 MOD, Short. The Red Teaming Handbook. p 40

38 MOD, Short. The Red Teaming Handbook. p 41

39 NATO, "The NATO Alternative Analysis Handbook." p 4

40 NATO, "The NATO Alternative Analysis Handbook." p4-5

41 Doerner Dietrich, "The logic of failure: Recognizing and avoiding error in complex situations," English translation. Metropolitan Books (1996). p 7

42 Dietrich, "The logic of failure: Recognizing and avoiding error in complex situations." p 7

43 Andrew Maher, "Strategic planners: A response to operational complexity," Journal Article, Australian Army Journal 13, no. 1 (2016), https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.663648981528906.. p 90

44 Ministry of Defence, AJP-5 Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations, (2019). p 3-18

45 US Army, ADP 5-0: The Operations Process, (2019). p 1-15

46 MOD, Short The Red Teaming Handbook. pp 49-50, 86-87, and

TRADOC G-2, Short The Red Team Handbook: The Army's guide to making better decisions. p 196-197

47 Walker, "Refining the Military Appreciation Process for adaptive campaigning. p 88-90

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.