Introduction

The Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) shares more similarities with the ‘Hero’s Journey’ story structure than military planners would care to admit. Both seek to impose structural constraints on understanding and representing the complex system that constitutes objective reality. Both produce the common output of a single, linear, relatively static narrative. But is such an output appropriate for JMAP? This author thinks not. In short, the output of JMAP should not directly resemble the output of a process used to produce fairytales.

JMAP’s narrative does not adequately represent the complex adaptive systems that are the subject and setting of operational plans. In discussing this issue, this article will explore systems theory, and how the intellectual approach of military design seeks to understand, manage and achieve advantage in the context of complexity. As will be shown, military design is an appropriate methodology for addressing complex systems, and therefore its meaningful inclusion in planning may overcome the narrative shortcomings of JMAP.

Currently, the scope for the implementation of design thinking in JMAP is considerable but entirely optional. Beyond time and experience, the incorporation of design thinking in JMAP is limited only by the discretion of the relevant Commander. But for those willing to confront the challenges of institutional conservatism, a pathway exists within the JMAP framework to depart from its conventionally reductionist approach and instead embrace a design focus that will push planning teams beyond the production of a simple, linear narrative.

There and Back Again: The Hero’s Journey

The Hero’s Journey was first outlined by the comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell in his 1949 work The Hero with a Thousand Faces.[1] Campbell claims the Hero’s Journey represents a universal narrative pattern or structure that is common to all stories across time, culture and language.[2] Broadly, the Hero’s Journey describes a central hero who ventures forth into an unfamiliar situation (departure) to face challenges and succeed in a decisive crisis (initiation), to then return to their familiar world victorious, having changed (return).

While not originally intended as a narrative planning tool, the Hero’s Journey soon attracted interest from writers and filmmakers seeking a practical guide to story creation. In the Hero’s Journey they found ancient mythic narrative structures and archetypes that, if followed and employed, would produce the bedrock of a compelling story with universal appeal. The most prominent of these early adopters was George Lucas, whose discovery of the Hero’s Journey during the planning phase of a story idea would result in the eventual production of the 1977 Star Wars film.[3] In the years that followed, the Hero’s Journey gained popularity in Hollywood, championed by writers and directors like Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Francis Coppola, and George Miller.[4] In 1985, the prevalence of the Hero’s Journey as a narrative planning tool was solidified by a now infamous seven-page memo detailing the process, produced by studio executive Christopher Vogler who would go on to story-doctor the struggling pre-production film The Lion King in 1992. The popular memo would evolve into Vogler’s full-length 1998 instructional planning guide The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers.[5] This guide quickly became ubiquitous in creative writing curricula and became a standard framework for story design in Hollywood.[6] In testament to its enduring influence, the concept has been further developed by industry professionals like Dan Harmon, who used Joseph Campbell’s work to underpin his ‘Story Circle’ construct; a concept distributed to junior writers at Netflix.[7] In practice, the influence of the Hero’s Journey in Hollywood and television has reached levels of high saturation, arguably fully integrated into and synonymous with modern conceptions of three-act structure.

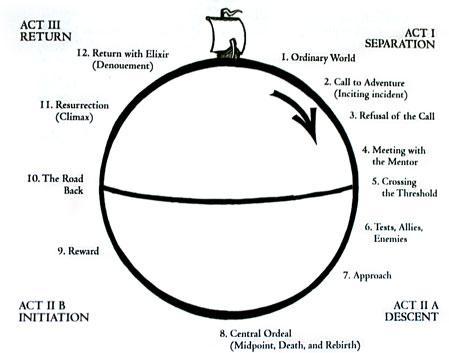

Figure 1. Vogler’s representation of the Hero’s Journey[8]

The Hero’s Journey is composed of a series of structural story episodes, circular in its overall design (Figure 1). These story episodes represent ‘functions’: non-literal significant actions or events that are ‘defined from the point of view of its significance for the course of the action’.[9] These functions are analogous to ‘decisive points’ on the lines of operation in JMAP’s Course of Action (COA) Development, each considered necessary to include in a narrative for the successful achievement of objectives. According to narrative structuralists, the explicit inclusion of these functions in a fictional work will result, at the very least, in a universally recognisable story.

But how does JMAP compare to the Hero’s Journey? What do both planning guides have in common, and how does this provide insight into JMAP’s effectiveness? There are two primary overlapping similarities between the two:

- Both processes are fundamentally concerned with narrative, and the production of a single, linear story; and

- Both seek to impose standardised structural constraints on the complex, dynamic system that constitutes objective reality.

JMAP as Narrative

Much has been written on the fundamentality of narrative to the human way of life, and to the achievement of political and operational objectives. Humans use narrative to structure and make sense of the complexity of reality.[10] According to Charles Tilly, narratives ‘do essential work in social life, cementing people’s commitments to common projects, helping people make sense of what is going on, channelling collective decisions and judgments, spurring people to action they would otherwise be reluctant to pursue’.[11] Strategic narratives are critical in a military strategic-operational context.[12] According to Lawrence Freedman, strategic narratives are ‘designed or nurtured with the intention of structuring the responses of others to developing events’.[13] These narratives are ‘strategic’ because they ‘do not arise spontaneously but are deliberately constructed or reinforced out of the ideas and thoughts that are already current’.[14]

Just as the primary output of the Hero’s Journey is a fictional story, so too is JMAP’s Concept of Operations (CONOP) a strategic narrative. The JMAP plan is a story that defines the relevant actors and relationships (characters), sequences of events (plot), anticipated tensions, conflicts, and environmental elements (setting), and the desired end-state (resolution). Not only that, the JMAP CONOP is a narrative of narratives, including within it the story of Australia’s national identity and strategic culture, as well as the story of Defence’s operational processes and practices, and the biases and assumptions entrenched in Defence’s institutional culture. Even the story produced in JMAP’s COA Development follows the core of the Hero’s Journey:

- Deployment of manpower and capability (departure / setup)

- Force employment (initiation / confrontation)

- Reconstitution (return / resolution).

So too does the JMAP process itself correspond with the stages of the Hero’s Journey. The Ordinary World of the Hero (in this case, the Joint Planning Team (JPT)), is disrupted by the Call to Adventure of the Commander’s Initial Guidance. In Scoping and Framing, the JPT questions the existence of the problem itself, showing reluctance or initial Refusal of the Call before Meeting with the Mentor, in this case the J2 cell, to establish the environmental and problem frames that will allow the Crossing of the First Threshold into the convergent world of Mission Analysis. From there, Tests, Allies, and Enemies will be envisioned and encountered in the production of multiple COAs before the Approach to the Inmost Cave, a ‘dangerous place … where the object of the quest is hidden’.[15] In approaching this cave, the JPT must reflect on the COAs that will be subject to critical scrutiny and war-gamed in The Ordeal of COA Analysis—a cave bearing the bones of many failed COAs. Success in this ordeal will present the Reward of validated COAs, with which the JPT will prepare a final briefing to the Commander on The Road Back to their ordinary world of operational implementation. With the agreement of the Commander on a preferred CONOP, the JPT experiences Resurrection to their ordinary world, emerging out of JMAP to Return with the Elixir of an approved and executable military operational plan.

Overall, JMAP is focussed on the development and production of a compelling, and operationally and strategically sound narrative. The CONOP is a story of operational success, itself a sub-story of Australia’s broader strategic narratives which structure the way Australia sees itself, and the action required to advance its interests.

That the output of JMAP is a narrative is not a bad thing—narratives are essential interpretive and explanatory tools. However, particular characteristics of JMAP’s narrative work to its detriment. First, the final output is only a single story. Second, but for the presence of stray branches and sequels, the JMAP narrative is linear. Third, the narrative perspective is from that of the protagonist (the ADF), and therefore only includes detail on what is highlighted by the interests and priorities of the ADF. Fourth, and finally, the JMAP CONOP is a point-in-time story, a generally static entity that will remain constant despite inevitable shifts in the material world. These are characteristics that are also shared by the stories produced from the Hero’s Journey, and are reflective of the structural properties of the planning processes themselves.

For fictional stories, these limiting characteristics are inconsequential, indeed necessary to achieve the broad consumption of a literary work; it does not matter that the story only reflects a point-in-time, protagonist-centred perspective of a narratively represented world. However, through military planning, the ADF seeks to produce a working model of the operational environment that the ADF can use to instigate transformational change. For that endeavour to be successful, the narrative must be a true representation of the actual system the ADF is seeking to influence. As modernity increases the multiplicity and complexity of the relationships, dependencies and consequent tensions in the dynamic systems that constitute operational environments, the ADF’s approach of producing a single, linear, static story of success becomes increasingly inappropriate.

Complex Systems and Narrative Representation

The kinds of systems the ADF seeks to influence are complex adaptive systems that defy Newtonian-styled analytical reductionism and linearity.[16] These systems are defined by the interactions, relationships, and tensions between their constitutive elements.[17] The interconnected components of a complex system are continually attempting to adapt to that system through learning and interaction.[18] This results in a system that is constantly evolving, thereby imposing inescapable unpredictability and the requirement for adaptive interpretation. To understand and achieve advantage in the context of continuous change and complexity, systems theory encourages an approach that treats the system holistically, recognising that influencing a single element is likely to produce changes across the rest of the system.[19] To understand and influence a system of this kind, advocates of systems theory recommend the application of feedback loops and non-linear, non-reductionist interpretive lenses.[20]

In producing a story, the narrator plays the part of a divine interventionist, bending objective reality to their will to produce a compelling story. This is an approach that is necessarily reductionist, breaking problems into manageable components to produce an understandable narrative. JMAP shares this reductionist approach, first in its imposition of a common formulaic analytical methodology, as well as in its oversimplification of the problems of a complex adaptive system.

The centre of gravity (COG) concept is a good example of JMAP’s proclivity for Newtonian reductionism. Clausewitz, its originator, describes the COG as ‘the hub of all power and movement, on which everything depends. That is the point against which all our energies should be directed..[21] In practice, the COG is inevitably found within the force structure of the adversary, leading to the problematic and probably unconscious presumption that there is a necessary causal relationship between targeting the enemy and achieving the desired operational end-state. In the Hero’s Journey, the COG is analogous to the primary means of resolving the central conflict. For example, in Star Wars: A New Hope, the plot-COG is Luke’s capacity to trust in the force, allowing him to fire a precise shot into the core of the Death Star through an external exhaust pipe.

While prevalent as plot devices in fiction, COGs are less effective in the context of complex adaptive systems. In these systems, it is unlikely that the exploitation or removal of one individual component will produce the effect of changing the system so that the original problem is no longer present. Rather, it is just as likely that the action will have unintended and unpredictable effects, or that the system will simply adapt and reconfigure itself to compensate for the loss of an individual component. According to Ben Zweibelson, it is not the case that ‘complex systems only express relationships in centralized hierarchical forms’ of the kind envisioned by a COG analysis.[22] Rather, nature also contains rhizomes, non-hierarchical, non-centralised entities that do not have a unified structure, and in which ‘any element may be connected with any other element..[23] In other words, rhizomes have no centre, representing a property that is both unanticipated by the COG approach, and unable to be influenced by a conventional JMAP methodology.

In both the Hero’s Journey and in JMAP, planners are worldmaking, building representations of objective reality that will be used to base a narrative. For JMAP, in not building a planning process around the requirements of complex adaptive systems, the represented world is a façade, a reductionist recreation devoid of the detailed interactions and relationships that define the real world. Just as stories benefit from a rich exposition of the world in which the narrative occurs, so too does an operational plan benefit from the identification, characterisation and representation of the dynamic system in which it will be applied. Without critical consideration of a system’s relationships, tensions, and emergent behaviours, JMAP does not produce a workable model of the operational environment and therefore does not allow a reliably effective means to transform the system to the planner’s desired end-state.

The problems associated with complex adaptive systems are increasingly recognised by military institutions.[24] In what follows, this article will argue that greater incorporation of design thinking in JMAP will enhance planning in the context of complexity, and therefore provide a pathway to resolving the narrative shortcomings of JMAP.

Design Thinking and Operational Narratives

Design thinking is an iterative, human-centred approach to problem-solving.[25] The process seeks to achieve innovation through the critical deconstruction of both the relevant problems themselves, as well as the analytic lenses through which we view the world. In doing so, design thinking aims to minimise the influence of the pre-existing biases, assumptions and beliefs of those undertaking the design process. In the last two decades, design thinking has become central to corporate innovation, and has significantly influenced military planning processes.[26]

The military design movement originated in Israel in the 1990s, materialising in what is still the most extreme and disruptive iteration of military design yet recorded: Systemic Operational Design (SOD). According to Ben Zweibelson, ‘SOD was designed not to enhance existing strategy, operational planning, or further the existing institutionalized war paradigm. SOD existed to deconstruct, challenge, destroy, and replace it’.[27] Traditional military decision-making processes were challenged by SOD’s introduction of concepts from postmodern philosophy and its focus on framing, disassembling and rebuilding the planners’ legacy systems.[28] In SOD, military planners create new and innovative ‘cognitive frames’ that allow the conceptualisation and representation of a complex system.[29] As Beaulieu-Brossard notes, the objective of SOD was to ‘deconstruct all assumptions, and to design the problem, metaphorically, and literally through mapping the system of the rival..[30]

SOD does not start with a pre-defined problem. Rather, the task of problem definition itself is the most critical step in the whole process. Nor is there a defined end-point to the planning process—feedback loops ensure that framing and reframing continue indefinitely, reflecting changes in the operational and strategic environment. Finally, the output of SOD is not a single, linear plan; rather, the output is the holistic representation of a complex adaptive system—a working model that identifies both the relationships and tensions between elements in the system, as well as how that system adapts and changes in response to particular actions or operations.[31] In this way, the operational commander has multiple possible narratives at their disposal, allowing them to test, modify, and switch between multiple plans.

Due to its disruptive nature and intellectual obtuseness, SOD was cast aside by theIsrael Defense Forces in the mid-2000s (although it is currently experiencing a resurgence).[32] However, the process was still highly influential abroad, and in the early 2010s military design thinking crept into both US and Australian doctrine.

While a far cry from SOD, JMAP includes a significant and well-integrated element of design thinking. Most prominently, the Scoping and Framing step of JMAP emphasises the importance of both defining the right problem, and constructing a workable model of the system of operations.[33] Less explicitly, JMAP also introduces design-influenced guidance and modifications to traditional military planning constructs. For example, while COG analysis is still a mandatory element of JMAP, the doctrine on COG is full of warnings and caveats, providing that ‘deducing and analysing the adversary COG has tended to become elevated above the need to define the true nature of the problem’.[34] In this way, while the doctrine retains the centrality of COG to military planning, it also acknowledges that it is an imperfect ontology that should be used more for broader operational understanding than for its practical value in achieving mission objectives.

According to proponents of military design, JMAP’s treatment of design is terminally simplified, and overshadowed by the linear, inflexible elements of the broader process.[35] However, JMAP is not totally rigid or constraining in its approach to design; doctrine provides a large degree of scope for extending and centralising design thinking in the military planning process. But the allowance for design in JMAP is optional, and how far that path is followed is entirely up to the relevant Commander.

Here is where an underappreciated but critical step in the JMAP process should be highlighted: the Commander’s Initial Guidance. It is at this stage where the Commander can either give the green light for design thinking, or bar that road by defining the problem themselves upfront, thereby imposing the familiar structural constraints of the traditional JMAP process. In making this decision, the Commander confronts the full force of institutional bias, culture and conservatism, pressured implicitly by a well-entrenched system of which the Commander themself is a product. Institutional culture is a formidable barrier to emphasising an approach of strong military design, and yet the structure of JMAP still invites that approach to be taken.

With the level of design-inclusion at the discretion of the Commander in their initial guidance, here—to use the terminology of the Hero’s Journey—there is truly a Call to Adventure. In this case, the Call to Adventure is one that invites a Commander to deviate from the structural bounds of JMAP, to cast away the determinative shackles of military process to embrace an expansive mode of problem-solving. In accepting this call, the Commander edges the military planning process closer to an end-result that de-emphasises the production of a single, linear narrative. Rather, the Commander prioritises a holistic perspective of the complex system in question, and encourages the formulation of multiple, contending narratives that are continually updated and implemented depending on how the model of the complex system reacts to operational action. The scope for this approach is possible within the framework of JMAP, but requires proactive and risk-tolerant action to accomplish.

Conclusion

The comparison of the Hero’s Journey with JMAP yields a simple but significant insight: the primary output of JMAP should not directly resemble the primary output of the Hero’s Journey. The Hero’s Journey produces a work of fiction in which the plot, characters, setting and resolution are not a true representation of the real world, but rather a figment of the arbitrary preferences and objectives of the author. Not only this, but the configuration and character of the story itself is determined by the structure and requirements of the ontology used to create it.

The JMAP CONOP, unfortunately, shares these characteristics; itself a single, linear, relatively static strategic narrative, representative of the biases, assumptions and beliefs built into the reductionist ontology that defines the JMAP process. According to systems theory, this approach is not sufficient to capture the dynamism of the complex adaptive systems that characterise the ADF’s operational environments. Rather, the ADF requires an approach that is capable of defining the interconnected relationships, dependencies, and tensions between the individual components of a system.

Advocates of design thinking claim that its incorporation into military planning is the primary means to achieve a comprehensive, high-fidelity representation of the operational environment. JMAP’s adoption of design principles and methodologies is significant but entirely optional. However, for those Commanders willing to accept design’s Call to Adventure, there lies a path that goes beyond the production of a single, bias-ridden operational narrative. For a Commander considering this path there stands before them a plethora of challenges, all born from the conservative risk intolerance that defines Defence’s planning culture. But there is a valuable boon that lies at the end of this design journey, readily obtainable within the framework of JMAP for any hero courageous enough to accept its call.

Bazin, Aaron. ‘Complex Adaptive Operations on the Battlefield of the Future’. Modern War Institute, February 28, 2017.https://mwi.westpoint.edu/complex-adaptive-operations-battlefield-future/

Beaulieu-Brossard, Philippe. ‘Systemic Operational Design or How I Began to Worry about the Dual Use of Critical Concepts’. 2015.

Blas, Nick. ‘Beyond Storytelling: Strategic Narratives in Military Strategy’. Æther: A Journal of Strategic Airpower & Spacepower 2, no. 1 (2023): 46–57.

Bruner, Jerome. ‘The Narrative Construction of Reality’. Critical Inquiry 18, no. 1 (1991): 1–21.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New World Library, 1949.

Carr, Sean D, Amy Halliday, Andrew C King, Jeanne Liedtka, and Thomas Lockwood. ‘The Influence of Design Thinking in Business: Some Preliminary Observations’. Design Management Review 21, no. 3 (2010): 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7169.2010.00080.x

Clausewitz, Carl von. On War. Translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. Princeton University Press, 1984.

Davis, Paul K. ‘Strategic Planning Amidst Massive Uncertainty in Complex Adaptive Systems: The Case of Defense Planning’. In Unifying Themes in Complex Systems, edited by Ali A Minai and Bar-Yam Yaneer, 201–14. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2006.

‘Episode 507: Dan Harmon LIVE’. Duncan Trusell Family Hour, June 8, 2022. https://www.duncantrussell.com/episodes/2022/6/8/dan-harmon-live

Freedman, Lawrence. The Transformation of Strategic Affairs. Routledge, 2017.

Kimbell, Lucy. ‘Rethinking Design Thinking: Part I’. Design and Culture 3, no. 3 (November 1, 2011): 285–306.https://doi.org/10.2752/175470811X13071166525216.

Krippendorff, Klaus. ‘Systems Theory’. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008.https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecs130

MacKenzie, Ian. ‘Narratology and Thematics’. MFS Modern Fiction Studies 33, no. 3 (1987): 535–44.

Morrison, Bradley J, Daniel Goldsmith, and Michael Siegel. ‘Dynamic Complexity in Military Planning: A Role for System Dynamics’. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society, 2008.

Prokhorov, Artem. ‘The Hero’s Journey and Three Types of Metaphor in Pixar Animation’. Metaphor and Symbol 36, no. 4 (October 2, 2021): 229–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2021.1919490

Propp, Vladimir. ‘Morphology of the Folktale: Second Edition.’ In Morphology of the Folktale. University of Texas Press, 1928.https://doi.org/10.7560/783911

Przybyło, Łukasz. ‘Systemic Operational Design – a Study in Failed Concept’. Security and Defence Quarterly 42, no. 2 (June 30, 2023): 35–54.https://doi.org/10.35467/sdq/163292

Sorrells, William T, Glen R Downing, Paul J Blakesley, David W Pendall, Jason K Walk, and Richard D Wallwork. ‘Systemic Operational Design: An Introduction’. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: US School of Advanced Military Studies, 2005.https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA479311

Tilly, Charles. Stories, Identities, and Political Change. Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.

Turner, John R and Rose M Baker. ‘Complexity Theory: An Overview with Potential Applications for the Social Sciences’. Systems 7, no. 1 (March 2019): 4–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems7010004.

Vogler, Christopher. ‘Joseph Campbell Goes to the Movies: The Influence of the Hero’s Journey in Film Narrative’. Journal of Genius and Eminence 2, no. 2 (2017): 9–23.

———. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. Michael Wiese Productions, 2007.

Williams, Clive. ‘The Hero’s Journey: A Mudmap for Change’. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 59, no. 4 (July 1, 2019): 522–39.https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167817705499

Zweibelson, Ben. Beyond the Pale. Air University Press, 2023.

———. ‘Rhizomes: In Paradox to “Centers of Gravity” and Centralized Hierarchies in War’. The Archipelago of Design (blog), December 16, 2021. https://aodnetwork.ca/rhizomes-in-paradox-to-centers-of-gravity-and-centralized-hierarchies-in-war/

———. Understanding the Military Design Movement: War, Change and Innovation. Taylor & Francis, 2023.

1 Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (New World Library, 1949).

2 Clive Williams, ‘The Hero’s Journey: A Mudmap for Change’, Journal of Humanistic Psychology 59, no. 4 (July 1, 2019): 523.

3 Christopher Vogler, ‘Joseph Campbell Goes to the Movies: The Influence of the Hero’s Journey in Film Narrative’, Journal of Genius and Eminence 2, no. 2 (2017): 11.

4 Vogler, Hero’s Journey in Film Narrative, 16.

5 Christopher Vogler, The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers (Michael Wiese Productions, 2007).

6 Artem Prokhorov, ‘The Hero’s Journey and Three Types of Metaphor in Pixar Animation’, Metaphor and Symbol 36, no. 4 (October 2, 2021): 232.

7 Duncan Trussell & Dan Harmon, ‘Episode 507: Dan Harmon LIVE’, Duncan Trusell Family Hour, June 8, 2022, https://www.duncantrussell.com/episodes/2022/6/8/dan-harmon-live https://www.duncantrussell.com/episodes/2022/6/8/dan-harmon-live

8 Vogler, Mythic Structure, 9.

9 Vladimir Propp, ‘Morphology of the Folktale: Second Edition’, in Morphology of the Folktale (University of Texas Press, 1928), 21. Quoted in Ian MacKenzie, ‘Narratology and Thematics’, MFS Modern Fiction Studies 33, no. 3 (1987): 536.

10 Jerome Bruner, ‘The Narrative Construction of Reality’, Critical Inquiry 18, no. 1 (1991): 4-5.

11 Charles Tilly, Stories, Identities, and Political Change (Rowman & Littlefield, 2002), 25.

12 Nick Blas, ‘Beyond Storytelling: Strategic Narratives in Military Strategy’, Æther: A Journal of Strategic Airpower & Spacepower 2, no. 1 (2023): 46.

13 Lawrence Freedman, The Transformation of Strategic Affairs (Routledge, 2017), 30.

14 Freedman, Transformation, 30.

15 Vogler

16 Paul K. Davis, ‘Strategic Planning Amidst Massive Uncertainty in Complex Adaptive Systems: The Case of Defense Planning’, in Unifying Themes in Complex Systems, ed. Ali A. Minai and Bar-Yam Yaneer (Springer, 2006), 204.

17 Klaus Krippendorff, ‘Systems Theory’, in The International Encyclopedia of Communication (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008), 2.

18 John R. Turner and Rose M. Baker, ‘Complexity Theory: An Overview with Potential Applications for the Social Sciences’, Systems 7, no. 1 (March 2019): 15.

19 Krippendorff, Systems Theory, 2.

20 Ben Zweibelson, Beyond the Pale (Air University Press, 2023), 31-41; Morrison, Goldsmith, and Siegel, ‘Dynamic Complexity in Military Planning: A Role for System Dynamics’. Proceedings of the 26th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society (2008): 5.

21 Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton University Press, 1984), 595.

22 Ben Zweibelson, ‘Rhizomes: In Paradox to ‘Centers of Gravity’ and Centralized Hierarchies in War’, The Archipelago of Design (blog), December 16, 2021, https://aodnetwork.ca/rhizomes-in-paradox-to-centers-of-gravity-and-centralized-hierarchies-in-war/.

23 Zweibelson, Rhizomes.

24 Aaron Bazin, ‘Complex Adaptive Operations on the Battlefield of the Future’, Modern War Institute, February 28, 2017, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/complex-adaptive-operations-battlefield-future/

25 Lucy Kimbell, ‘Rethinking Design Thinking: Part I’, Design and Culture 3, no. 3 (November 1, 2011): 287.

26 Sean D. Carr et al., ‘The Influence of Design Thinking in Business: Some Preliminary Observations’, Design Management Review 21, no. 3 (2010): 58; Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 2-3

27 Ben Zweibelson, Understanding the Military Design Movement: War, Change and Innovation (Taylor & Francis, 2023), 117.

28 William T. Sorrells et al., ‘Systemic Operational Design: An Introduction’. (Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: US School of Advanced Military Studies, 2005), i.

29 Sorrells, SOD: An Introduction, 19.

30 Philippe Beaulieu-Brossard, ‘Systemic Operational Design or How I Began to Worry about the Dual Use of Critical Concepts’, (2015): 6. Quoted in Zweibelson, Design Movement, 134.

31 Sorrells, SOD: An Introduction, 33-4.

32 Łukasz Przybyło, ‘Systemic Operational Design – a Study in Failed Concept’, Security and Defence Quarterly 42, no. 2 (June 30, 2023): 35.

33 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 2-3.

34 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 3-6.

35 Zweibelson, Military Design Movement, 140.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.