Introduction

The Australian Defence Force's principal planning doctrine, Australian Defence Force Procedures (ADFP) 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, requires little refinement. It provides military planners with a foundation to develop integrated campaigning strategies with coalition partners to combat military problems. The current strategic environment will need the ADF to integrate further with coalition partners to plan against an escalating threat within the Indo-Pacific.[1] While ADFP 5.0.1 already aligns with coalition partners' overall planning processes, definitions and sub-steps must be aligned. Military planners also need the freedom to choose planning methodologies to improve force integration and develop plans in line with current circumstances.

This paper will show that ADFP 5.0.1's five foundational steps of the Military Appreciation Process (MAP) already support planning at all levels of war. The five MAP steps align with numerous planning procedures and methodologies with coalition partners (US, UK, UN), historical decision-making processes, civil agencies, project management and design thinking. From the outset, doctrine is the foundational document that enables untrained planners to progress with planning with little understanding of the organisation's mechanisms. The ADF does not intend for doctrine to be prescriptive. Instead, it serves as a statement of the philosophy the military will apply to particular circumstances. Planners then use their collective experiences and cautiously judge how future battlefields might be dealt with to develop a successful plan.[2] Though the Department of Defence in its entirety does not utilise the ADFP 5.0.1 for its dedicated planning process, this paper will demonstrate that the MAP is fit for military planners and only requires slight improvements to be a central repository for all ADF planning.

This paper will first understand the current ADF planning doctrine and procedures across the spectrum of war. This essay's analysis will then demonstrate how the five steps align with US, UK, and UN, historical decision-making processes, civil agencies, and project management planning procedures and methodologies. The analysis will show how design thinking aligns with the ADF MAP. Finally, it will highlight issues and propose solutions to the current ADF MAP doctrine to strengthen the ADF planning doctrine. This paper will recommend that the ADF only refine its planning procedures to centralise and consolidate doctrine internally and externally and create planning 'toolbags' for each macro step of the MAP. Doing so will enable ADF planners to respond better and plan against threats in our strategic environment.

Australian Planning Doctrine

The MAP is a planning and decision-making tool valuable for commanders and their staff to create a desirable course of action in response to a situation across the spectrum of operations. It is an iterative and cyclical approach led by any command level to develop an operational or tactical plan.[3] It is essential to consider the levels of war when examining military organisational planning and the challenges they face. Most military planning occurs between the levels of war, through understanding and distilling higher commanders' intent and plans to what is appropriate for a subordinate force to execute their assigned tasks. In this way, military organisations can create successful strategies and ensure their operations are aligned and ultimately successful.

The military strategic level concentrates on ‘link[ing] military instrument[s] of national power to a whole-of-government approach to national security’, focused on developing and coordinating high-level plans to achieve ‘an end-state favourable to the national interest’.[4] The ADF does not have a distinct planning doctrine for this level but ultimately does planning in a joint or interagency environment.[5] Therefore, the Joint MAP (JMAP), or at least its components, are often used to develop suitable plans and orders for subordinate units.[6] ADF Headquarters and Joint Operations Command focus on this area to create an operational theatre strategy.

The Staff MAP (SMAP) distils the Joint orders within a single Service headquarters environment. It creates an operational to tactical strategy to execute the tasks across all the Battlespace Operating Systems (BOS).[7] [8] The operational level concentrates on planning and implementing tasks from a Divisional Headquarters to a Battlegroup Headquarters. A staff, acting upon the commander's guidance and leadership, undertakes planning to design diverse actions on the battlefield, with a particular emphasis on coordination and synchronisation. At this point, each BOS planner analyses the scenario, with the support of their individual and separate BOS planning doctrine, to support each step of the MAP.[9] The SMAP ultimately achieves the commander's intent on the battlefield.

The tactical level focuses on the battles, engagements, and activities of tactical units or task forces that carry out specific missions. At the tactical level, it is imperative to plan and execute promptly. The ADF supports tactical commanders with the Individual MAP (IMAP) for Pre-H hour planning and the Combat MAP (CMAP) for Post-H hour planning.[10] The IMAP and CMAP, although based on the five steps of the MAP, are a near-rational approach to the current set of tactical circumstances and are used as a quick reference guide to counteract an opposing force's actions. As such, the IMAP and CMAP are essential tools to ensure the successful execution of tactical objectives.

The four MAPs—JMAP, SMAP, IMAP and CMAP—employ the same five steps:

- Preliminary Analysis & Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace

- Mission Analysis

- Course of Action Development

- Course of Action Analysis

- Decision & Execution

As the level of war reduces, planners or commanders require less guidance within the sub-steps, allowing for better focus and more time for reconnaissance and rapid execution. Ultimately, the four MAPs provide a streamlined approach to mission planning, allowing commanders to make informed decisions and execute plans quickly. ADF commanders and planners will apply these steps to understand the current scenario regardless of the environment.

Comparisons of Military, Training and Civil Planning Processes

When militaries operate unilaterally or multilaterally, or form coalitions with other government agencies or non-government organisations, planning and execution must be inherently linked and synchronised. Even though the armed forces of many Western countries and agencies utilise different planning processes by name, they are all intrinsically linked in their macro process and design. These steps include framing a problem, examining a mission, developing, analysing, and comparing actions, selecting the best course of action, and producing a plan or order. We must synchronise partnered coalitions or agencies to ensure the entire force can work together to achieve the same goal. The following table demonstrates that ADFP 5.0.1's fundamental steps are aligned externally with other militaries, government agencies or non-government organisations, and internally for training and subordinate planning.

| Organisation | Appreciation or Decision Making Process | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADF Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) | 1. Scoping and Framing | 2. Mission Analysis | 3. Course of Action - Development | 4. Course of Action - Analysis | 5. Decision & Execution |

| ADF Systems of Australian Defence Learning (SADL) | 1. Analyse | 2. Design | 3. Develop | 4. Implement/Evaluate | |

| Army Staff Military Appreciation Process (SMAP) | 1. Preliminary Analysis | 2. Mission Analysis | 3. Course of Action - Development | 4. Course of Action - Analysis | 5. Decision & Execution |

| Army Individual MAP/Combat MAP | 1. Mission Analysis | 2. Enemy/Threat Analysis | 3. Terrain Analysis | 4. Develop and Execute | |

| Boyd's OODA Loop | 1. Observe | 2. Orientate | 3. Decide | 4. Act | |

| Army ASDA Cycle | 1. Act | 2. Sense | 3. Decide | 4. Adapt | |

| Civilian Project Management | 1. Initiate | 2. Define | 3. Design | 4. Development | 5. Implement & Close |

| Australian National Emergency Management Agency - Crisis Appreciation and Strategic Planning (CASP) | 1. Define the Environment | 2. Mission Analysis | 3. Developing Courses of Action | 4. Execution | |

| Canadian Forces Operational Planning Process (OPP) | 1. Initiate | 2. Orientation | 3. Course of Action - Development | 4. Plan Development | 5. Plan Review |

| NATO Comprehensive Operational Planning Process (COPP) | 1. Indicators & Warnings | 2. Assessment | 3. Response Options Development | 4. Planning | 5. Execution 6. Transition |

| UK Joint Operations Planning (JOP) | 1. Initiation | 2. Mission Analysis | 3. Courses of Action - Development | 4. Courses of Action - Analysis 5. Courses of action validation and comparison | 6. Commander’s decision 7. Plan Development |

| US Army Military Decision-Making Process (MDMP) | 1. Receipt of Mission | 2. Mission Analysis | 3. COA Development | 4. COA Analysis 5. COA Compare | 6. COA Approve & Orders |

| US Joint Operation Planning Process (JOPP) | 1. Planning Initiation | 2. Mission Analysis | 3. Course of Action - Development | 4. Course of Action - Analysis 5. Wargaming, COA Comparison | 6. COA Approval 7. Plan or Order Development |

| US Marine Corps Planning Process (MCPP) | 1. Problem Framing | 2. Course of Action - Development | 3. COA wargame 4. COA comparison and decision | 5. Orders development 6. Transition | |

Even though the above table shows that each organisation's underlying appreciation or decision-making process is aligned, this is the only layer they unite. The reason for this is the different approaches each nation takes in dissecting the scenario or information presented. When we compare the JMAP to the United Kingdom's and inherently NATO's same-level Allied Joint Publication-5 (JOP), we can see that both Mission Analysis sub-steps vary. The JMAP involves nine sub-steps compared to five of the UK JOP.[12] Though the steps figuratively cover the same content, the Australian doctrine is more prescriptive in its methodology. It uses a Philosophical Centre of Gravity analysis from military theorist Carl von Clausewitz. The philosophical approach aligns more with the United States Joint Publication 5-0 - Joint Planning (JOPP), using the same philosophical manoeuvrist approaches to focus the limited military resources on targeting or protecting the 'will to fight.’'[13] We can see the separation and over-prescriptive nature of the Australian doctrine in the remaining sub-steps of COA-Development—ADF’s three versus UK’s two; COA-Analysis: ADF’s two versus UK’s one; and Decision and Execution: ADF’s three versus UK’s one. We must understand the various planning approaches of each nation so that we can coordinate military strategy and operational planning when coalitions form, even if the overall planning process is the same.

Internally to the ADF, each MAP subordinate step is also inherently dissimilar, with unalike outputs required at different stages. Some argue that the subordinate SMAP at the operational-tactical level is more prescriptive due to the thickness of the doctrine, with ADFP’s having 228 pages versus LWD’s 304 pages. Comparing the JMAP to the SMAP can cause an Army planner to get lost, become confused, and feel frustrated due to each MAP step's different inputs and outputs. For example, Joint planners issue a Warning Order to subordinates after Step 1: Scoping and Framing, with little to no appreciation of the force, mission objectives and tasks. As opposed to at the end of Step 2: Mission Analysis within the SMAP when those critical elements are known. Again, the MAP is overly simplified at the tactical level, however, for good reason. IMAP and CMAP analyse limited information to focus on the speed of planning for rapid execution, allowing junior commanders to maintain or seize the initiative.

Ultimately, the ADF doctrine is more authoritarian than other nations' military planning doctrine, the 5-Phase Project Management Guide, and the Department of Home Affairs' Crisis Appreciation and Strategic Planning (CASP) Guidebook.[14] So why is doctrine, both externally at the joint level and internally between the levels of war, different within each sub-step? In the first instance, it comes from the history of each military and the amount of time they have tried, tested and invested in its relevance to the current strategic environment. As Michael Evans suggests, to remain relevant, ‘the ADF must embrace a number of reforms; these reforms include adopting a functional approach to operational concept development, improving joint doctrine, developing comprehensive campaign planning and introducing significant reforms into the joint professional military education system’.[15] Within the ADF, Services train their members from the tactical to the strategic levels. The junior commanders and planners commence their MAP journey by learning the most prescriptive doctrine and, through time and experience, require less rigid steps as they elevate through the levels of war. As Christopher Tuck concludes in understanding the challenges of joint warfare, ‘joint warfare requires a strong understanding of the distinctive attributes of each Service and domain and how these can be integrated towards a common purpose’.[16] Therefore, Service planners transfer the knowledge of Service planning into the joint planning environment.

Even though ADF MAP doctrine is more prescriptive in its subordinate steps, the overall planning processes are the same regardless of the level of war or partnered organisations. By aligning planning methodologies within the force and across organisations, the ADF can ‘deepen its engagement and collaboration with partners’[17] to be prepared for ‘the prospect of [a] major conflict in the region’. This alignment enables ADF planners to embed themselves easily within a coalition or joint headquarters and remain relevant in planning.

Design thinking

The ADF MAP and Design Thinking are intrinsically synchronised. Some argue that both are fundamentally different. The MAP is a highly linear process that does not support adaptation or complex problem solving for all situations.[18] Conversely, design thinking is multidisciplinary and allows ADF planners to address, manage and overcome complex problems to remain relevant and ahead of an adversary decision-making cycle.[19] This paper would argue that both are fundamental requirements of contemporary operations. Regardless of the type of problem, both problem-solving methods are essential to help ADF planners find the best solution.

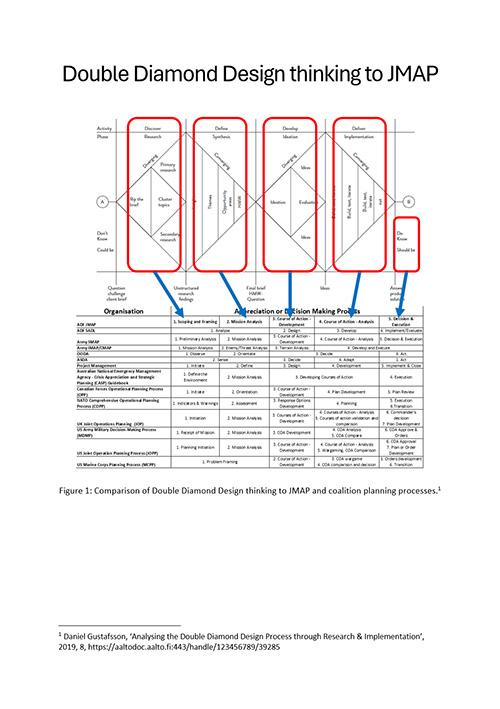

Design thinking is not new to military planning. Over the past two decades, military planners have been tackling new and complex problems with a new frame of thinking in their linear planning processes. In the mid-2000s, the US military became interested in Systemic Operational Design after a British Design Council simplified design thinking into a 'Double Diamond' model.[20] The Double Diamond model, in the below figure, exemplifies design thinking's central idea of divergent and convergent thinking to a four-step process of ‘discover, define, develop and deliver’ to generate innovative and adaptive solutions.[21] Using design thinking, US military planners adopted outside-the-box plans in conducting Counter-Insurgency Operations in the Middle East.[22] Design thinking also reduces plan development time by providing a holistic problem-solving approach, enabling planners to learn and correct mistakes rapidly through planning.

Figure 1: Comparison of Double Diamond Design thinking to JMAP and coalition planning processes.[23]

The ADF is not exempt from the need to innovate and address complex problems. As Post, Walker and other authors contemplate, the MAP is overly prescriptive and 'does not support adaptation or complex problem solving’, pushing the ADF to consider and renovate its planning processes.[24] From the immediate demonstration of the figure above, doctrine writers do not need to make a fundamental shift in the MAP to adopt other planning methods. The processes already align at the macro level. Internally, each planning process slightly diverges. However, the MAP sub-steps still follow divergent and convergent thinking methods. An example of this is in Step Three: COA-D, which is a divergent thinking approach that has the sub-steps of 'develop detailed courses of action', which infers divergent thinking to generate possible solutions, and then the following sub-step of 'test courses of action' implies convergent thinking, in analysing and assessing those COAs.[25] Nevertheless, the ADF will encourage discussion within the arms profession to remain innovative so planners can adapt and solve complex issues.

JMAP Problems – Solutions

Internally Centralise and consolidate. Australian doctrine consistently tells planners to task-organise to be tailored and efficient with the resources; by doing so, planners can streamline and orientate quicker to solving problems. However, with so many areas the ADF plans for, why has the ADF not centralised and consolidated all planning doctrine? The ADF Doctrine Library is supposed to be the single repository of doctrinal knowledge within Defence. Recently, under CDF's direction, doctrine is trying to be unified under one hierarchy and repository: One Defence, One Doctrine.[26] However, within the ADF, Navy, Army and Air Force Doctrine Libraries, there are still too many MAPs. There are different planning doctrines for each level of war and BOS areas.[27] However, the Australian Navy and Air Force may or may not have their doctrine correct, as there are no tactical or operational planning procedures. Within the Air Application Doctrine Library there is a placeholder for ADF-A(A)-5; however, its status is in draft with no release date. Within Navy Publications, the N5 series is a set of strategic policies surrounding international engagements. The absence of planning doctrine can suggest that the ADFP 5.0.1 is the only procedural planning doctrine they are introduced to, which already centralises, consolidates and aligns joint planning across ADF.

Recommendation One. The ADF should continue to centralise and consolidate all planning doctrine under 'One Defence – One Doctrine' policies to integrate force planning fully. Centralising and consolidating means reducing each level of war MAP and BOS planning doctrine to the essential planning considerations against the five steps of the MAP within two overarching documents: Australian Defence Force - Philosophical - 5 Planning and ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process. Specific BOS or Service planning doctrine should complement the capstone documents without duplication.

Externally Centralise and consolidate. With each military's planning processes so closely aligned, there is an opportunity to centralise and consolidate planning doctrine. Similarly, although it technically is only a cover page to the UK doctrine, NATO has a centralised planning doctrine. Australia and other militaries inherently have their own 'flavour' of planning and definitions. When it comes to collaboration, definitions and different sub-steps are what hinder integration or slow planning. The ADF has and will continually review its planning processes and doctrine to remain relevant for the contemporary environment. ADF planning teams have adopted other nations' methodologies to use a non-linear, iterative approach to understand the battlespace, challenge assumptions, redefine problems, and create innovative solutions. Doctrine writers released the Joint Doctrine Note 1-16 - Operation Assessment in 2016, incorporating Operational design and management into ADF planning procedures.[28] Coalition planning documents provide most of these additional planning tools. For example, the Mission success criteria, Measures of performance and effectiveness have been taken from US Joint Publication 5-0 and US Army Field Manual 5-0.[29]

Recommendation Two. The ADF should support a review of all coalition planning processes and definitions to centralise and consolidate doctrine into the same macro planning steps and glossary. Centralising and consolidating will enable greater integration of the forces when it comes to planning and execution of military operations.

Create planning 'Toolbags' for each Macro Step. The ADFP 5.0.1 is highly prescriptive in how planners must progress within each step and sub-steps. This paper shows that the engrained methods within each planning step do not matter as divergent and convergent design thinking occurs. The military planner needs the freedom to choose different planning methodologies within each macro step. This 'toolbag' needs to be a range of processes across the other organisations' planning to enable the greatest flexibility and application to a greater degree of circumstances. Doing so would support Walker's 'Alternate model' for planning to ‘accommodate input from a diverse range of models and methods that planners may see fit to employ from time to time’.[30] Overall, if the planner conducts the macro steps, they will find a suitable solution.

Recommendation Three. The ADF inserts an upfront disclaimer within the ADFP 5.0.1 to support planners' understanding of 'Modifying the military appreciation process—to be as detailed as time, resources, experience, and the situation permit’.[31] To demonstrate that the planning process is not intended to be prescriptive and give a choice to the planner, we should follow what the US Army Field Manual 5-0 commences with. [32]

Recommendation Four. The ADF should bolster the available planning methodology sub-steps within each macro step of the MAP. The ADFP 5.0.1 should centralise numerous coalition planning sub-methodologies to allow military planners to choose their planning process pathway. This 'toolbag' of planning tools would enable planners to apply the most straightforward planning approach to reach the desired outcome quickly.

Conclusion

The ADF continually reviews its planning doctrine to remain relevant. By using non-linear, iterative planning methods, ADF planning teams can understand battlespaces, challenge assumptions, redefine problems, and develop innovative solutions. The ADF has incorporated design thinking ideas into its planning doctrine, as it promises innovation by supplementing existing mental models and focusing on complex problems from a different perspective. The ADFP 5.0.1 provides military planners with a foundation to create integrated campaigning strategies with coalition partners to combat military issues. Planners must understand that doctrine does not prescribe a solution to planning but provides insights on approaching solutions. Planners need to abbreviate the steps of the MAP to fit time-constrained circumstances to produce a satisfactory plan.[33]

The initial objective of this paper was to comprehend the existing ADF planning doctrine and procedures throughout the range of warfare. Subsequently, it showed alignment with the US, UK, and UN, historical decision-making processes, civil agencies, and project management planning procedures and methodologies. Furthermore, it has assessed how design thinking is already in sync with the ADF MAP. This paper has proposed that the ADF only needs to refine its assortment of planning procedures to centrally and comprehensively consolidate doctrine and establish planning 'toolbags' for every Macro Step of the MAP. By doing so, ADF planners will be better equipped to respond and strategise effectively against threats in our strategic environment.

Simply put, it doesn't matter what planning process organisations use; they all follow a recurring trend of divergent and convergent thinking to generate effective solutions to complex contemporary problems. What matters is that the diverse planning team follows the same process to harmonise the team to work together.

‘Allied Joint Publication-5: Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations, Edition A Version 2’. UK Ministry of Defence (MOD), May 2019.

‘Australian Defence Force Procedures (ADFP) 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, Edition 2’. Commonwealth of Australia, 2019.

‘Australian Defence Force‑Capstone‑0 Foundations of Australian Military Doctrine, Edition 4’. Commonwealth of Australia, 2021.

‘Australian Defence Force-Philosophical-7 Learning, Edition 3’. Commonwealth of Australia, 2021.

Butler, Dwayne, Angelena Bohman, Lisa Colabella, Julia Thompson, Michael Shurkin, Stephan Seabrook, Rebecca Jensen, and Christina Burnett. Comprehensive Analysis of Strategic Force Generation Challenges in the Australian Army. RAND Corporation, 2018. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2382.

‘Canadian Army Command and Staff College The Operational Planning Process: OPP Handbook, CACSC-PUB-500’. Canadian Army Command and Staff College, April 2018. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/dnd-mdn/army/lineofsight/files/articlefiles/en/CACSC-PUB-500-2018.pdf.

‘Crisis Appreciation and Strategic Planning (CASP) Guidebook’. Department of Home Affairs, n.d.

Department of Defence. ‘Defence Strategic Review 2023’. Commonwealth of Australia, 2023.

‘Doctrine | The Forge’. Accessed 25 October 2023. https://theforge.defence.gov.au/doctrine.

Evans, Michael. ‘Centre of Gravity Analysis in Joint Military Planning and Design: Implications and Recommendations for the Australian Defence Force’. Security Challenges 8, no. 2 (2012): 81–106.https://www.jstor.org/stable/26468953.

———. ‘The Closing of the Australian Military Mind: The ADF and Operational Art’. Security Challenges 4, no. 2 (2008): 105–31.https://www.jstor.org/stable/26459144.

Field, Chris. ‘Five Ideas: On Planning’. The Cove, 22 November 2018. https://cove.army.gov.au/article/five-ideas-planning.

Gustafsson, Daniel. ‘Analysing the Double Diamond Design Process through Research & Implementation’, 2019. https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi:443/handle/123456789/39285.

Jackson, Aaron P. ‘Center of Gravity Analysis “Down Under”: The Australian Defence Force’s New Approach’. National Defense University Press Joint Forces Quarterly, no. 84 (2017): 81–85. https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/1038829/center-of-gravity-analysis-down-under-the-australian-defence-forces-new-approach/.

Jackson, Aaron P., Brandon Pincombe, Alex Ryan, Nick Kempt, Ashley Stephens, Nikoleta Tomecko, Darryn J. Reid, et al. ‘Design Thinking: Applications for the Australian Defence Force’. Joint Studies Paper Series No. 3, 2019.

‘Joint Doctrine Note 1-16 - Operation Assessment’. Commonwealth of Australia, 2016.

‘Joint Warfare Publication 5-00 - Joint Operations Planning’. UK Ministry of Defence (MOD), March 2004.

Kelly, Justin, and Mike Brennan. ‘OODA versus ASDA: Metaphors at War’. Australian Army Journal 6, no. 3 (2009): 39–51.

Kochanowska, Magda, Weronika Rochacka Gagliardi, and with reference to Jonathan Ball. ‘The Double Diamond Model: In Pursuit of Simplicity and Flexibility’. In Perspectives on Design II: Research, Education and Practice, edited by Daniel Raposo, João Neves, and José Silva, 19–32. Springer Series in Design and Innovation. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79879-6_2.

‘Land Warfare Doctrine 5-1-4: The Military Appreciation Process’. Commonwealth of Australia, 2015.

‘Marine Corps Warfighting Publication (MCWP) 5-10 - Marine Corps Planning Process’, 10 August 2020.

‘Military Decision Making Process Handbook’. US Center for Army Lessons Learned, March 2015. https://usacac.army.mil/sites/default/files/publications/15-06_0.pdf.

Post, Ryan. ‘The Joint Military Appreciation Process: The Good, The Bad and Some Alternatives’. The Forge, 2022. https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2022/joint-military-appreciation-process-good-bad-and-some-alternatives.

Stanczak, John, Peyton Talbott, and Ben Zweibelson. ‘Designing at the Cutting Edge of Battle: The 75th Ranger Regiment’s Project Galahad’. Special Operations Journal 7, no. 1 (2 January 2021): 1–16.https://doi.org/10.1080/23296151.2021.1905224.

The Cove. ‘Introduction to the Military Appreciation Process (MAP)’. Accessed 19 October 2023. https://cove.army.gov.au/article/introduction-military-appreciation-process-map.

Tuck, Christopher. Understanding Land Warfare. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2022. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003096252.

UK MoD. ‘Allied Joint Publication-5 Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations, Edition A, Version 2’. NATO Standardization Office, May 2019.

‘US Army Field Manual 5-0 - Planning and Orders Production’. US Department of the Army, May 2022.

US Joint Chiefs of Staff. ‘Joint Publication 5-0 - Joint Planning’. US Department of Defense, 1 December 2020.

Walker, David. ‘Refining the Military Appreciation Process for Adaptive Campaigning’. Australian Army Journal 8, no. 2 (2011): 85–100.

Weiss, Joseph W., and Robert K. Wysocki. 5-Phase Project Management: A Practical Planning & Implementation Guide. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1992.

1 Department of Defence, ‘Defence Strategic Review 2023’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 2023), 23–24.

2 ‘Australian Defence Force‑Capstone‑0 Foundations of Australian Military Doctrine, Edition 4’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 2021).

3 ‘Land Warfare Doctrine 5-1-4: The Military Appreciation Process’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 2015), 35.

4 Dwayne Butler et al., Comprehensive Analysis of Strategic Force Generation Challenges in the Australian Army (RAND Corporation, 2018), 13, https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2382.

5 Ryan Post, ‘The Joint Military Appreciation Process: The Good, The Bad and Some Alternatives’, The Forge, 2022, https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2022/joint-military-appreciation-process-good-bad-and-some-alternatives.

6 ‘Australian Defence Force Procedures (ADFP) 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, Edition 2’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 2019).

7 Battlespace Operating System (BOS) is defined as: ‘The combination of personnel, collective training, major systems, supplies, facilities, and command and management organised, supported and employed to perform a designated function as part of a whole.’

8 ‘Land Warfare Doctrine 5-1-4: The Military Appreciation Process’, 21.

9 BOS planning doctrine is as follows:

• Manoeuvre = LWD 5-1-4 The Military Appreciation Process, 3 July 2015

• Fire Support = LWP-CA (OS) 5-3-3 Joint Fires and Effects - Planning, Execution and Targeting (Land) 28 October 2010, AL2, 11 December 2018

• Information Operations = LWP-G 3-2-1 Operations Security, 28 May 2021

• Intelligence, Surveillance & Reconnaissance = LWP-INT 2-1-8 Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace, 30 November 2016

• Mobility and Survivability = LWP-CA (ENGR) 1-2-1 Engineer Operations in Support of Formation Tactics, 3 September 2019

• Air Defence = LWP-CA (GBAD) 6-3-2 Air Ground Operations, yet to be published

• Command & Control = LWP-G 0-5-1 Staff Officers Guide 7 March 2017 and DN 1-2010 Commanders' Guide to Operational Analysis, 9 June 2010

• Combat Service Support = LWP-CSS 4-0-1 Combat Service Support in the Theatre: Interim, 15 December 2015

10 ‘Introduction to the Military Appreciation Process (MAP)’, The Cove, accessed 19 October 2023, https://cove.army.gov.au/article/introduction-military-appreciation-process-map

11 ‘Australian Defence Force Procedures (ADFP) 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, Edition 2’; ‘Australian Defence Force-Philosophical-7 Learning, Edition 3’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 2021); ‘Land Warfare Doctrine 5-1-4: The Military Appreciation Process’; ‘Introduction to the Military Appreciation Process (MAP)’; Justin Kelly and Mike Brennan, ‘OODA versus ASDA: Metaphors at War’, Australian Army Journal 6, no. 3 (2009): 39–51; Joseph W. Weiss and Robert K. Wysocki, 5-Phase Project Management: A Practical Planning & Implementation Guide (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1992); ‘Canadian Army Command and Staff College The Operational Planning Process: OPP Handbook, CACSC-PUB-500’ (Canadian Army Command and Staff College, April 2018), https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/dnd-mdn/army/lineofsight/files/articlefiles/en/CACSC-PUB-500-2018.pdf; UK MoD, ‘Allied Joint Publication-5 Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations, Edition A, Version 2’ (NATO Standardization Office, May 2019); ‘Joint Warfare Publication 5-00 - Joint Operations Planning’ (UK Ministry of Defence (MOD), March 2004); ‘Military Decision Making Process Handbook’ (US Center for Army Lessons Learned, March 2015),https://usacac.army.mil/sites/default/files/publications/15-06_0.pdf; US Joint Chiefs of Staff, ‘Joint Publication 5-0 - Joint Planning’ (US Department of Defense, 1 December 2020); ‘Marine Corps Warfighting Publication (MCWP) 5-10 - Marine Corps Planning Process’, 10 August 2020; ‘Crisis Appreciation and Strategic Planning (CASP) Guidebook’ (Department of Home Affairs, n.d.).

12 ‘Australian Defence Force Procedures (ADFP) 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, Edition 2’, 3–1; ‘Allied Joint Publication-5: Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations, Edition A Version 2’ (UK Ministry of Defence (MOD), May 2019), 4–7.

13 US Joint Chiefs of Staff, ‘Joint Publication 5-0 - Joint Planning’, 178–85.

14 Weiss and Wysocki, 5-Phase Project Management: A Practical Planning & Implementation Guide; ‘Crisis Appreciation and Strategic Planning (CASP) Guidebook’.

15 Michael Evans, ‘The Closing of the Australian Military Mind: The ADF and Operational Art’, Security Challenges 4, no. 2 (2008): 105, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26459144

16 Christopher Tuck, Understanding Land Warfare, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2022), 25, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003096252

17 Department of Defence, ‘Defence Strategic Review 2023’, 18-23.

18 David Walker, ‘Refining the Military Appreciation Process for Adaptive Campaigning’, Australian Army Journal 8, no. 2 (2011): 85–100; Post, ‘The Joint Military Appreciation Process: The Good, The Bad and Some Alternatives’.

19 Aaron P. Jackson et al., ‘Design Thinking: Applications for the Australian Defence Force’, Joint Studies Paper Series No. 3, 2019, 2.

20 Magda Kochanowska, Weronika Rochacka Gagliardi, and with reference to Jonathan Ball, ‘The Double Diamond Model: In Pursuit of Simplicity and Flexibility’, in Perspectives on Design II: Research, Education and Practice, ed. Daniel Raposo, João Neves, and José Silva, Springer Series in Design and Innovation (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022), 20, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79879-6_2

21 Kochanowska, Gagliardi, and with reference to Jonathan Ball, 25.

22 John Stanczak, Peyton Talbott, and Ben Zweibelson, ‘Designing at the Cutting Edge of Battle: The 75th Ranger Regiment’s Project Galahad’, Special Operations Journal 7, no. 1 (2 January 2021): 4, https://doi.org/10.1080/23296151.2021.1905224

23 Daniel Gustafsson, ‘Analysing the Double Diamond Design Process through Research & Implementation’, 2019, 8, https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi:443/handle/123456789/39285

24 Post, ‘The Joint Military Appreciation Process: The Good, The Bad and Some Alternatives’; Walker, ‘Refining the Military Appreciation Process for Adaptive Campaigning’; Aaron P. Jackson, ‘Center of Gravity Analysis “Down Under”: The Australian Defence Force’s New Approach’, National Defense University Press Joint Forces Quarterly, no. 84 (2017): 81–85, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/1038829/center-of-gravity-analysis-down-under-the-australian-defence-forces-new-approach/; Chris Field, ‘Five Ideas: On Planning’, The Cove, 22 November 2018, https://cove.army.gov.au/article/five-ideas-planning; Michael Evans, ‘Centre of Gravity Analysis in Joint Military Planning and Design: Implications and Recommendations for the Australian Defence Force’, Security Challenges 8, no. 2 (2012): 81–106, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26468953

25 ‘Australian Defence Force Procedures (ADFP) 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, Edition 2’, 152.

26 ‘Doctrine | The Forge’, accessed 25 October 2023,https://theforge.defence.gov.au/doctrine.

27 BOS planning doctrine is as follows:

• Manoeuvre = LWD 5-1-4 The Military Appreciation Process, 3 July 2015

• Fire Support = LWP-CA (OS) 5-3-3 Joint Fires and Effects - Planning, Execution and Targeting (Land) 28 October 2010, AL2, 11 December 2018

• Information Operations = LWP-G 3-2-1 Operations Security, 28 May 2021

• Intelligence, Surveillance & Reconnaissance = LWP-INT 2-1-8 Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace, 30 November 2016

• Mobility and Survivability = LWP-CA (ENGR) 1-2-1 Engineer Operations in Support of Formation Tactics, 3 September 2019

• Air Defence = LWP-CA (GBAD) 6-3-2 Air Ground Operations, yet to be published

• Command & Control = LWP-G 0-5-1 Staff Officers Guide 7 March 2017 and DN 1-2010 Commanders' Guide to Operational Analysis 9 June 2010

• Combat Service Support = LWP-CSS 4-0-1 Combat Service Support in the Theatre: Interim, 15 December 2015

28 ‘Joint Doctrine Note 1-16 - Operation Assessment’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 2016).

29 US Joint Chiefs of Staff, ‘Joint Publication 5-0 - Joint Planning’; ‘US Army Field Manual 5-0 - Planning and Orders Production’ (US Department of the Army, May 2022).

30 Walker, ‘Refining the Military Appreciation Process for Adaptive Campaigning’, 91.

31 ‘US Army Field Manual 5-0 - Planning and Orders Production’, 90.

32 ‘US Army Field Manual 5-0 - Planning and Orders Production’, 90.

33 ‘US Army Field Manual 5-0 - Planning and Orders Production’, 90.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.