Introduction

Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1—Joint Military Appreciation Process[1] (JMAP) provides guidance for the planning of operations and campaigns within the broader doctrine framework. Other fundamental doctrines within the framework include the philosophical doctrine of Planning[2], Campaigns and Operations,[3] and Land Warfare Doctrine 5.1.4—The Military Appreciation Process.[4] This framework provides practitioners with crucial theory, underpinning knowledge, and guidance for the detailed planning process. Similarly, a project architecture has been established by the US Program Management Institute (PMI), providing standards for portfolio management, program management and project management as well as supporting guides such as risk management.[5] This framework of documents provides the required guidance to conduct planning at the required level within the project architecture.

This essay will compare the Australian military planning process with the Project Management Institute planning process to identify the applicability of the JMAP for planning operations and campaigns. This essay will demonstrate that the JMAP provides a good foundation for planning operations only; however, through its reductionist approach, it misses opportunities in planning and is not suited to campaigns. This essay will do this by first examining the levels of planning in the two frameworks, aligning campaigns with portfolios and operations with programs. Secondly, it will examine how the two systems align with complex problems through the Cynefin Framework. Finally, it will consider the applicability of the process within the broader planning framework and the applicability of the JMAP to Defence. This will demonstrate that the JMAP provides a structured planning process for operations, limited by its inability to handle the complexity involved in the problems.

Levels of Planning

Program and portfolio management have individual planning standards and associated guides targeted at their specific level of planning. The project management architecture is considered across levels from portfolio to program to project to product. These varying levels allow planning to stay at a level relevant to the input and output while enabling planning at the higher and lower levels. A program is defined as ‘related projects, subsidiary programs, and program activities managed in a coordinated manner to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually’.[6] A portfolio is defined as ‘Projects, programs, subsidiary portfolios, and operations managed as a group to achieve strategic objectives’.[7] Program management focuses on organisational level challenges and is predominantly based on organisational theories, focused on achieving outcomes.[8] Portfolio management links strategic objectives to programs and projects, utilising strategy theory as the basis.[9] These fundamental differences identified between portfolios and programs create a difference in how to plan most effectively and the planning level of detail. The program and portfolio management standards contain similar language; however, the standards are different to align with the desired output type. The required skills for undertaking program and portfolio management are separate as the different outputs drive different abilities within the personnel.[10] Similar to portfolio and program management, military planning and the military planning appreciation process are conducted at different levels.

The JMAP is for planning campaigns and operations despite the different characteristics.[11] The JMAP, along with the Military Appreciation Process, the Individual Military Appreciation Process and the Combat Military Appreciation Process, are Australian military planning processes. [12] These processes have a similar flow of steps with similar language; however, they are adapted to the specific level of planning required. These three additional planning processes are for the tactical level, while the JMAP guides the operational level planning across operations and campaigns. These different levels of planning and adaption of the planning process align with the approach taken through the project architecture. Within the JMAP doctrine, an operation is defined as:

A campaign is defined as:

Based on these two definitions, there is a significant similarity between an operation and a campaign. The primary difference is moving from a group of tactical actions to a group of military operations, changing the size and scale of the force. In particular, unlike program and portfolio management, both end states can be linked to a strategic objective. These definitions align more closely with a portfolio in the project architecture due to the strategic objective. The introduction chapter for the JMAP highlights that the planning process must be used differently for a campaign than an operation. However, there is no further articulation of the differences between these two processes throughout the planning process.[14] Additionally, the doctrine describes the initial commander's guidance that will be received, which has already turned the strategic objective into an end state and does not fully align with the definition of campaign and operation. In more recent doctrine, the definition of an operation has changed.

A single planning process does not suitably cover the difference in input and output expected by a campaign and operation. According to the recently released Australian Philosophical doctrine Campaigns and Operations, an operation is defined as:

The definition of a campaign has remained unchanged. This change in definition has created a further delineation between campaigns and operations based on the difference in input and required output. Based on these definitions, there is a clear difference between operations and campaigns. Of note, campaigns aim to achieve a strategic objective, whereas operations aim to achieve directed outcomes. This change retains alignment between a campaign and a portfolio; however, it now aligns an operation with a program in the project architecture. The guidance at each level will change due to the complexity and span of the required end state from the operation or campaign. The scoping and framing components of the planning process will differ significantly. Based on these definitions, a campaign and an operation have different purposes they are trying to achieve, utilising different force sizes. As is seen through the difference in planning processes between portfolio management and program management, the focus of the planning process aligns with the end state and a different planning process is applied to achieve a strategic objective versus an outcome. The Military Appreciation Process has different levels of planning; with the updated Campaign definition, this should now also include a tailored process for campaign planning. The JMAP applies to the complex problem solving required for an operation.

Complex Problems

The JMAP has turned planning for a complex problem into a linear process more aligned with a complicated process. The Cynefin Framework presents four types of systems to classify the different relationships within a system.[16] The framework divides systems based on the relationship, known or unknown. Simple and complicated are on the known side, where relationships within the system are known and can be defined. Complex and chaotic systems comprise many interacting agents, resulting in difficult to define relationships on the unknown side. This framework provides a baseline to understand the type of problem and, therefore, an appropriate way to solve it. Problems requiring solving through operational level plans will sit within the complex to the chaotic realm.[17] These plans involve human behaviour, which is inherently complex and has influences beyond the planner's control that will lead to continual changes. The visual representation of the JMAP is a diagram with boxes representing the steps positioned left to right. Although arrows indicate the feedback loop expected to occur when undertaking the process, the numbering of the steps and sequential presentation of the information portray a linear process.[18] This diagram enables individuals new to the process to understand the critical components of the process quickly. However, it creates an immediate perception of a linear process. The conduct of military operations, and therefore its planning, is neither linear nor static.[19] Through this consideration of a linear process, individuals will miss the true complexities in military operations and are less likely to regularly review earlier stages in the process to ensure ongoing validity. These potential shortcomings of the JMAP are identified in the introduction chapter of the doctrine.[20] This linear process is very different to the planning process per the PMI’s Program Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK).

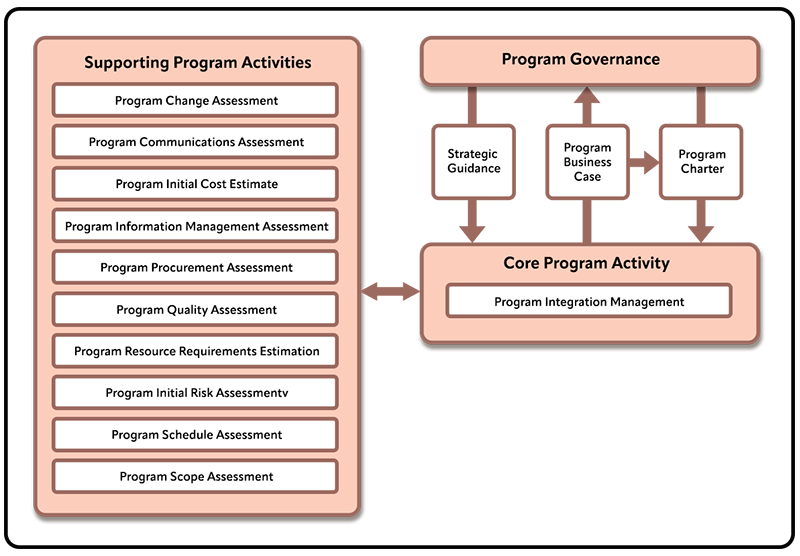

The PMBOK keeps the complete system in consideration throughout the document. A program has three key phases and five performance domains. The five performance domains of Strategy Alignment, Benefits Management, Stakeholder Engagement, Governance and Life Cycle Management are the core of the PMBOK Standard.[21] The phases are sequential in timing from start to finish. However, the performance domains are consistent across all phases to allow constant management throughout the program. Within a program, the three phases are program definition, program delivery and program closure. These are captured under the Lifecycle Management Performance domain.[22] Each of these phases has underpinning activities. The program definition phase will be compared to the JMAP as the comparable phase. This phase has two key sections: program formulation and program planning. For each phase, the representation of the identified activities is as per the below example for the formulation activities.

Figure 1. Program Formulation Phase Activity Interaction[23]

Each of the supporting activities links to a performance domain that is often outside the Lifecycle Management domain. This representation of the activities keeps the program governance and strategic direction at the centre of all activities. Additionally, there are no arrows to show a flow of information through the different activities. Instead, analysis of all activities occurs through an integration mechanism to support the end state. A brief description of each activity provides a baseline, including what it is and why it is vital in a program. However, there is no description of how to achieve the activity, a far less prescriptive approach than the JMAP. This relies on the staff to determine how the various elements will be achieved based on the specific program they are delivering. This relies on a higher level of skills and knowledge for the individuals conducting the tasks. This process is, therefore, more suited to skilled staff with the skills and knowledge to apply the framework to the problem. However, the Program Management Standard is easier to tailor than the JMAP.

The JMAP is difficult to tailor to the specific planning situation. The Standard for Program Management allows for the conceivable range of complexities in a program.[24] It focuses on key performance domains that span the duration of the program and does not simply focus on the planning phase. The planning phase activities link to the range of performance domains. It also allows tailoring of the theory to the complexity of the analysed system. The JMAP provides a list of inputs, the required sub-steps and a list of outputs for the applicable step at the beginning of each chapter. Additionally, further detailed explanations for each sub-step provide the prescriptive process.[25] When conducting military planning in a time-constrained environment, this process provides an easy understanding and clear order for the planning. Due to the presence of a checklist, practitioners will focus on achieving all items on the checklist. This reduces the ability of the practitioner to adapt the process to the time available and specific situation, as doing so will mean they will miss elements of the checklist. Additionally, the connection to the strategic guidance can be lost in the later stages of the process as this is not specified within the checklist regularly. PMBOK provides a basis for program planning to support complex systems. Alternatively, the JMAP is a simple linear process requiring limited knowledge of the system to suit a broad range of military staff. However, due to the specificity of the doctrine, it can be more difficult to tailor the JMAP to the time and situation and across the different types of operations.

Fit within the system

The JMAP identifies operational risk management and operational assessment as essential elements of the planning process. The doctrine identifies that the JMAP is both a decision support and risk identification tool.[26] This highlights the importance of understanding the presence and criticality of risks throughout the planning and execution phases. Despite the remainder of the process being highly prescriptive by step, these elements are described in more detail in the introduction than during the prescriptive step detail. The JMAP identifies the difference between operational design and the arrangement of operations within the process.[27] Operational design is the basis of the JMAP steps one and two. The arrangement of operations is the basis for steps three, four, and five. The arrangement of operations has eight specific elements; however, of these elements, only risk and assessment should be considered from the commencement of planning in steps one and two.[28] Although important throughout the process, neither risk nor assessment is represented on the process diagram. The assignment of risk and assessment to the arrangement of operations constrains their consideration in the early phases. The program management standard provides the detail around risk and assessment by considering uncertainty and measurement mainly within the strategy alignment and benefits management performance domains. Due to the importance of risk, there is also a standalone standard for managing risk in portfolios, programs and projects.[29] Both processes apply a similar approach to risk and assessment, where they have been described and considered in elements across the planning cycle. This is consistent with how the program management standard approaches planning with the performance domains; however, it is unique in the JMAP. Risk and assessment are critical from planning through to execution; however, by being incorporated differently in the JMAP, they can be undervalued.

The JMAP is a defined part of the planning process conducted for an operation. The Australian Planning Philosophical doctrine provides the broader planning context and underlining theory used to develop the Military Appreciation Processes across the use spectrum.[30] This means individuals undertaking the JMAP should be cognisant of additional doctrine to harness the value of the process. The project management architecture has divided its standards by level, where the inputs and outputs feed into the respective superior and subordinate level planning documents.[31] By keeping the broader context in a single document for each level, it is easier for users to remain aware of the full scope of the processes required. The end of the JMAP is at the decision and concept of operations development, with the plan development and execution considered outside the process. The Philosophical planning document expands on this changeover from planning staff to operational staff.[32] However, this change relies on detailed planning outside this process. For this to be successful, clear articulation of the risks identified and proposed assessment metrics is essential. These elements are not in the description of the handover in the planning doctrine and have limited guidance in the JMAP. Where program management is a single document, the JMAP is a part of the broader planning process at the level. As such, planners need to be aware of the other planning doctrine. In particular, the documentation of the plan, including risk and assessment metrics, to maintain alignment with strategic guidance is essential for success.

The context in which a planning process is implemented drives the value. The program management standard and associated guidance suit a range of environments and contexts. There has been further research into how this standard applies to different contexts.[33] This demonstrates that the standard requires adaptation to the environment and specific tasks. The JMAP has been adapted for use by Australian military professionals using heuristics as a core theory.[34] The value of the process leverages the gained experience and knowledge in the organisation before engaging in the planning process. The JMAP provides an adequate planning solution that suitable, experienced military professionals can easily understand. However, those involved in the plan, from giving guidance through to executing, need to understand the constraints of the process and understand where it fits organisationally to ensure it remains aligned to the required outcome and risks do not escalate. The similarities between the program management standard and the JMAP show the validity of overlaying civilian planning processes in the military context. Due to the value gained by implementing program and portfolio management practices, there is ongoing academic research into the subjects to further improve processes.[35] As research continues into elements of the project management architecture, the learnings and theories should continue to be considered to update the JMAP.

Conclusion

To make the process accessible and usable by a range of military professionals, the JMAP has lost some of the versatility demonstrated by the Program Management Standard. However, so long as practitioners understand these constraints, the process is suitable for Defence for the planning of operations. The planning process provides a suitable framework to work through complicated problems in a structured and ordered manner to develop a plan. However, this does risk losing the complexity in the planning. Handing the plan over for further detailed planning and execution increases this risk. The planning process is not suitable for campaign planning due to its restricted ability to translate a strategic objective into a plan and assess success against the strategic objective. The research and development activities undertaken towards improving civilian planning processes, such as program management and portfolio management, will continue to improve the value of the JMAP for operations and campaigns, respectively.

Artto, Karlos, Miia Martinsuo, Hans Georg Gemünden, and Jarkko Murtoaro. ‘Foundations of Program Management: A Bibliometric View’. International Journal of Project Management 27, no. 1 (January 1, 2009): 1–18.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.10.007.

Australian Army. LWD 5.1.4 The Military Appreciation Process. Department of Defence, 2015.

Clegg, Stewart, Catherine P Killen, Christopher Biesenthal, and Shankar Sankaran. ‘Practices, Projects and Portfolios: Current Research Trends and New Directions’. International Journal of Project Management 36, no. 5 (July 1, 2018): 762–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2018.03.008.

Department of Defence. ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. 2nd ed. Canberra, AUSTRALIA: Department of Defence, 2019.

———. ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations. Canberra, AUSTRALIA, 2021.

———. ADF-P-5 Planning. 1st ed. Canberra, AUSTRALIA, 2022.

Miterev, Maxim, Mats Engwall, and Anna Jerbrant. ‘Exploring Program Management Competences for Various Program Types’. International Journal of Project Management 34, no. 3 (April 1, 2016): 545–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.07.006.

Pellegrinelli, Sergio, Ruth Murray-Webster, and Neil Turner. ‘Facilitating Organizational Ambidexterity through the Complementary Use of Projects and Programs’. International Journal of Project Management 33, no. 1 (January 2015): 153–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.04.008.

Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge and The Standard for Project Management. 7th ed. Pennsylvania, USA: Project Management Institute, 2021.

———. The Standard for Portfolio Management. 4th ed. Pennsylvania, USA: Project Management Institute, 2017.

———. The Standard for Program Management. 4th ed. Pennsylvania, USA: Project Management Institute, 2017.

———. The Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects. 1st ed. Pennsylvania, USA: Project Management Institute, 2019.

Smith, CR. Design and Planning of Campaigns and Operations in the Twenty-First Century. Study Paper / Land Warfare Studies Centre 320. Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre, 2011.

Snowden, David. ‘Complex Acts of Knowing: Paradox and Descriptive Self‐awareness’. Journal of Knowledge Management 6, no. 2 (January 1, 2002): 100–111.https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270210424639.

Zweibelson, Ben. ‘One Piece at a Time: Why Linear Planning and Institutionalisms Promote Military Campaign Failures’. Defence Studies 15, no. 4 (December 2015): 360–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2015.1113667.

1 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process, 2nd ed. (Canberra, AUSTRALIA: Department of Defence, 2019).

2 Department of Defence, ADF-P-5 Planning, 1st ed. (Canberra, AUSTRALIA, 2022).

3 Department of Defence, ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations (Canberra, AUSTRALIA, 2021).

4 Australian Army, LWD 5.1.4 The Military Appreciation Process (Department of Defence, 2015).

5 Project Management Institute, The Standard for Portfolio Management, 4th ed. (Pennsylvania, USA: Project Management Institute, 2017); Project Management Institute, The Standard for Program Management, 4th ed. (Pennsylvania, USA: Project Management Institute, 2017); Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge and The Standard for Project Management, 7th ed. (Pennsylvania, USA: Project Management Institute, 2021); Project Management Institute, The Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects, 1st ed. (Pennsylvania, USA: Project Management Institute, 2019).

6 Project Management Institute, The Standard for Program Management, 3.

7 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge and The Standard for Project Management, 4.

8 Karlos Artto et al., ‘Foundations of Program Management: A Bibliometric View’, International Journal of Project Management 27, no. 1 (January 1, 2009): 10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.10.007.

9 Artto et al., 10.

10 Maxim Miterev, Mats Engwall, and Anna Jerbrant, ‘Exploring Program Management Competences for Various Program Types’, International Journal of Project Management 34, no. 3 (April 1, 2016): 545–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.07.006.

11 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process, 1–1.

12 Australian Army, LWD 5.1.4 The Military Appreciation Process.

13 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process, ii, vii.

14 Department of Defence, 1–7.

15 Department of Defence, ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations, 4.

16 David Snowden, ‘Complex Acts of Knowing: Paradox and Descriptive Self‐awareness’, Journal of Knowledge Management 6, no. 2 (January 1, 2002): 105, https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270210424639.

17 Ben Zweibelson, ‘One Piece at a Time: Why Linear Planning and Institutionalisms Promote Military Campaign Failures’, Defence Studies 15, no. 4 (December 2015): 366,https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2015.1113667.

18 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process, fig. 1.1.

19 CR Smith, Design and Planning of Campaigns and Operations in the Twenty-First Century, Study Paper / Land Warfare Studies Centre 320 (Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre, 2011), 9.

20 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process, 1–9.

21 Project Management Institute, The Standard for Program Management, 25.

22 Project Management Institute, chap. 7.

23 Project Management Institute, tbls. 8–1.

24 Sergio Pellegrinelli, Ruth Murray-Webster, and Neil Turner, ‘Facilitating Organizational Ambidexterity through the Complementary Use of Projects and Programs’, International Journal of Project Management 33, no. 1 (January 2015): 154,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.04.008.

25 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process.

26 Department of Defence, 1C – 15.

27 Department of Defence, 1-4–5.

28 Department of Defence, 1–5.

29 Project Management Institute, The Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects.

30 Department of Defence, ADF-P-5 Planning.

31 Project Management Institute, The Standard for Portfolio Management; Project Management Institute, The Standard for Program Management; Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge and The Standard for Project Management.

32 Department of Defence, ADF-P-5 Planning, 84.

33 Miterev, Engwall, and Jerbrant, ‘Exploring Program Management Competences for Various Program Types’, 547.

34 Department of Defence, ADF-P-5 Planning, 11.

35 Stewart Clegg et al., ‘Practices, Projects and Portfolios: Current Research Trends and New Directions’, International Journal of Project Management 36, no. 5 (July 1, 2018): 762–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2018.03.008.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.