Introduction

The Australian Defence Force (ADF), like many militaries, takes great pride in its organisational ability to plan both in peacetime, when more deliberate contingency plans can be developed, and in times of crisis when dynamic, but no less thorough, planning is required. In both planning contexts, the ADF primarily relies on the Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP). Since 1999, the JMAP has been the primary framework for Australian military planners to approach operational-level planning in a joint environment.[2] Though it is a useful planning process with merit, contemporary trends in warfare require a sophisticated, agile, and flexible planning process that offers scalable options to decision makers in an increasingly complex environment.[3] This essay posits that elements of the Design Thinking process should be included in the JMAP, namely in the Mission Analysis step and during Course of Action development. Incorporation and integration of these elements would allow ADF planners to grapple with the complex problems that arise during operational-level planning in a modern, accelerated, multi-domain conflict scenario. This essay will first explore the ADF Operational and Strategic level planning approach—the JMAP—and identify the strengths and weaknesses of the approach. It will then compare the JMAP with Design Thinking as a new concept for planners, before concluding.

Joint Military Appreciation Process

The JMAP was introduced into the ADF joint operational planning doctrine in 1999, after first appearing in the Australian Army Land Warfare doctrine in 1992.[4] It was designed to be an enabling framework to ensure a structured planning process for ADF planners. It facilitated a consistent problem-solving approach across the ADF. The doctrine and planning process has evolved as Australia’s relationship with key allies—the United States and the United Kingdom—have shaped Australia’s military processes, education and thinking.[5]

The Process involves six macro steps, each with numerous sub-steps, and is intended to be executed by a multi-disciplinary team of specialists across fields including Human Resources, Intelligence, Operations, Logistics, Future Plans, Communications, Health, and Legal. The JMAP approach is intended to ensure a standard process that is applicable across the three military Services—the Navy, Army and the Air Force. This standardised approach enables a multi-disciplinary group to come together as a unified, integrated planning team and develop a workable plan within resource constraints, which may include time, information deficit and staffing limits. Notably, the ADF is not the sole large organisation investing in integrated multidisciplinary teams—many business industries have also operationalised the concept.[6]

At the single-Service level, in the Australian Army, a version of JMAP is most often taught to tactical-level leaders. The Army introduces the Military Appreciation Process (note the lack of ‘joint’) at the Individual level during initial Officer Training at the Royal Military College – Duntroon, and to Junior Non-Commissioned Officers during the All-Corps Training Continuum. It is taught and assessed throughout the Officer Training Continuum—from the All-Corps Captains Course, All Corps Majors Course to Corps-specific career progression courses. Non-Commissioned Officers are also trained and practised in the Process; however, they are generally involved in the Staff Military Appreciation Process (SMAP) at the brigade-level and below, from the rank of sergeant to warrant officer. The SMAP is generally used for domain-specific problems that require specialist input. The introduction to the JMAP typically occurs at the Divisional level and above, when the other Services are involved. This is the level where the majority of Army officers and senior Army soldiers will be exposed to, and utilise, the JMAP.

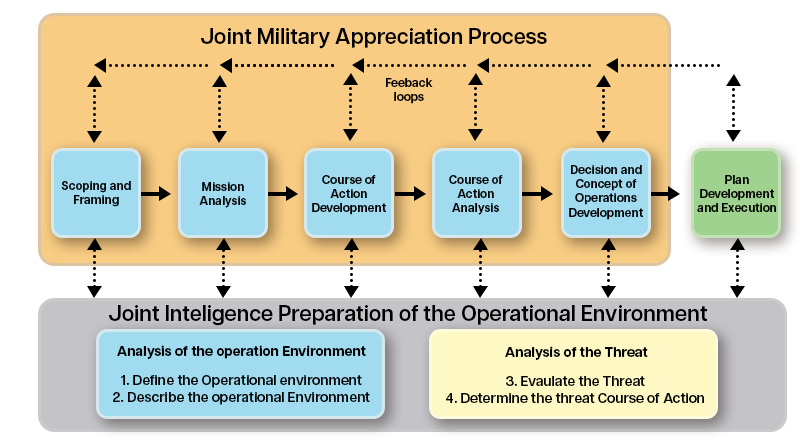

The Joint Operations Planning Course is designed for all three Services to come together to learn how to plan in a joint environment, for joint operations, and is delivered by the ADF Warfare Training Centre.[7] It allows for a full simulation of the process and is aprerequisite for many members posted to Headquarters Joint Operations Command—the ADF’s Operational level planning organisation. The below image outlines the Process steps, and illustrates how the intelligence picture informs all aspects of the approach. It also highlights the linear nature of the Process. However, the Process allows for planners to revert to a previous step if the information or environment changes.

The Joint Military Appreciation Process (ADDP 5.0) Figure 1.1[8]

Philosophical Underpinnings for the Planning Process

Philosophically, planning and shared imagination have always been a strength of humankind. Harari argues that a human’s ability to cooperate at a greater scale and complexity than other creatures is what separates us from animals.[9] For humans to be able to cooperate with complete strangers (allies, other members of a military, religious groups etc), we need a set of ‘common myths that exist only in people’s collective imagination’.[10] It is a great source of strength for militaries to be able to unite behind a common identity—collective belonging to an organisation. This strength is an opportunity in the Planning process; it aids with future planning endeavours. Whilst some animals have demonstrated an ability to plan beyond short-term needs, such as stalking behaviour and associative learning,[11] researchers are yet to see evidence of human levels of cognition, or the ability to cooperate at the scale and dynamism of humans.[12] Human cooperation at scale is a critical capability for military leadership and in planning. Smelser defines myths as ‘a belief or concept that embodies a visionary ideal’[13]. One of the most important aspects of a plan is for those developing and executing the plan to be able to collectively share the imagination, and be able to communicate with sufficient detail to enable timely implementation and execution. It also demands great imagination and problem-solving abilities to comprehend not only the challenges of one's actions at a great scale but also the reactions and counter-actions of other stakeholders within the operating environment.

JMAP shortcoming 1: linear nature

Planning practitioners commonly cite that the key downfall of the JMAP is its linear nature—the requirement that each step is to be done in succession, progressing only after the step before is completed. As planners progress through each JMAP step, they must carry assumptions forward that may or may not be proven as fact. When incorrect assumptions are used, or if information from the earlier steps of the planning process change—such as the essential tasks or critical intelligence about the adversary—then the Process often requires preceding steps to be completely redone. This results in inefficiency with duplicative efforts, and potentially increased risk due to compressed planning time. Planning doctrine even outlines the JMAP’s linear is a flaw and offers that, ‘if required by the circumstances, it may need to be applied in a less rigid fashion, with steps repeated, re-ordered or omitted’.[14] Despite this doctrinal warning, the process of adapting the process or omitting steps is typically not taught to planning practitioners.

The JMAP’s linear nature can be slow to adapt when new variables are included. As John Boyd identified in his experience in the Korean War as a fighter pilot, the ability to Observe, Orientate, Decide and Act in a loop (‘OODA Loop’) faster and more accurately than an adversary can be the defining factor of victory.[15] Boyd later developed his OODA Loop findings into a military strategy approach. This approach is premised on agility and how complex adaptive systems can have a disproportionate effect on a larger, more technically advanced but linear-thinking adversary. A contemporary example of the OODA Loop planning approach was the battle between the United States Joint Special Operations Command (along with Coalition partners) against Al-Qaeda insurgents in Iraq 2003. US General Stanley McChrystal wrote of his experience in breaking the conventional, hierarchical thinking within the special forces against a more complex and adaptive force in his book Team of Teams.[16] General McChrystal’s approach required delegation of authority to subordinates, increased information sharing and rapid interaction with the complex adaptive system (Al-Qaeda) in order to test assumptions about how it would react, and how it could be shaped, in order to be defeated. The current format of the JMAP is evidently not agile or iterative enough for application in these settings.

Most contemporary military operations are complex, dynamic and multi-dimensional, particularly against an adaptive adversary. Although military operations have historically rarely been simple, they are becoming more and more complex and high tempo with the technological advantages of interconnectivity, through the internet and affordable smartphones, leading to information saturation[17] through the cyber domain and, more recently, space domain. The speed of warfare has increased over the last few decades, recognised by the Australian Army through ‘accelerated warfare’ under the former Chief of Army, Lieutenant General Rick Burr, AO, DSC, MVO.[18]

Accelerated warfare is centred on the reality that the pace of change in the operating environment is faster than it has ever been, and may well be slower than future war scenarios. This concept illuminates the need for an agile and rapid decision-making process in order to enable decision superiority over an adversary:

Accelerated Warfare as a description of ‘how we respond’ means owning the speed of initiative to outpace, out-manoeuvre and out-think conventional and unconventional threats. It requires excellence in the art and science of decision making as well as deep thinking about Army’s role in understanding, shaping and influencing the environment.[19]

Planning is also becoming increasingly difficult due to increasing urbanisation. The United Nations claims that more than half of the world’s population lives in urbanised environments and this number is on the rise.[20] For militaries, the trend has led to denser and more complex operating environments, particularly for land and air forces. This environment introduces significant threat variables into planning. When entering a complex environment with a significant threat variable, it can make accurate force structure, logistics and health planning problematic. John Spencer also argues that urban environments carry high risk in managing civilian casualties in an opaque, densely populated environment. It can also be extremely costly post-conflict to make safe and rebuild cities that have been scarred by urban warfare.[21] Baghdad and Mosul in Iraq are two examples of cities that have experienced fierce urban environment fighting over the last two decades. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has also identified that conflicts are becoming more protracted. ‘The average length of time the ICRC has been present in the countries hosting its ten largest operations is more than 36 years’.[22] These contemporary trends in warfare require a sophisticated, agile, sufficiently rigorous and flexible planning process that can offer scalable options to meet the needs of Australia’s government of the day.

JMAP shortcoming 2: Centre of Gravity concept

Another contentious part of the existing ADF JMAP doctrine is the Centre of Gravity (COG) analysis, conducted in the Mission Analysis step (step 2). This analysis applies to both the own force and the adversary, and can be applied to any other stakeholders that the planning team determine are appropriate. This is a subjective area of planning. Zweibelson argues this concept is based on a Newtonian concept that Clausewitz developed (later published after his death as On War) which reflected a time of warfare that was fought in only two domains—the land and the sea.[23]

In Clausewitz’s time of war, battles were fought in more limited ways than modern warfare. Arguably, modern warfare spans over five domains at a more accelerated and complex rate than in Clausewitz’s writings. The COG concept, at its core, is an analogy taken from the then-contemporary scientific understanding of physics and mathematics which more closely relate to complicated systems. The premise is that, taking an action in one domain to target a critical vulnerability can subsequently lead to operational success. It is based on Manoeuvre Warfare theory, which advocates for most efficiently targeting the adversary’s weakest point with your greatest strength, which will have the most significant impact on an adversary’s motivation to fight. This deduces that an adversary will fight for one centrally important reason, and discounts the view that an adversary could be motivated for multiple reasons, of equal importance. What this concept fails to account for is complex adaptive systems, including those of advanced states. These advanced states are almost certainly able to recognise their own weaknesses, and seek to vigorously protect and/or build multiple levels of redundancy into a ‘characteristic, capability, or locality from which a force derives its freedom of action, physical strength, or will to fight’.[24] Whilst there is a science to warfare, it underestimates the human dimension of decision making and dismisses concepts such as Strategic Empathy. Strategic Empathy demands a deeper understanding of what motivates a state, and requires an understanding of how geography, history and politics intersect to influence the state.[25] As Zilincik asserts, it is also contrary to the popular but oversimplified view from Thucydides—that nations are motivated to go to war out of fear, honour or interest.[26]

Design Thinking – an alternative to JMAP

Design Thinking is both 'an analytical and creative process that engages a person in opportunities to experiment, create and prototype models, gather feedback, and redesign’.[27] Its theoretical foundations come from a variety of disciplines; engineering, social sciences, and design.[28] Though often discussed in engineering circles,[29] it is also used in the business world, highlighting its utility across a spectrum of settings. Design Thinking enables creative and bespoke solutions to complex problems that are non-linear and that are not possible to solve through a linear code or described by a basic flow chart. This element is what sets apart Design Thinking from the JMAP.

Separate from complex problems, 'complicated problems’ can be described as a sequence where the relationship between parts and dependencies are measurable and predictable.[30] A modern car is an example of a complicated system. It includes a sophisticated engine, a fuel management system, a cooling system, advanced electronic engine management, a transmission, and other components that operate together to achieve a capability. When a car breaks down, it is able to be diagnosed in a timely manner by a trained and qualified technician. In a Military Planning context, complicated problems are often distilled to the tactical level to be solved with specific actions. In the land domain, it may include clearing an enemy from a hill in order to secure key terrain that dominates a geographic area and gives a marked advantage to the military force. In a humanitarian and disaster relief mission, an example may include clearing main roads to enable aid agencies to reach telecommunications and water infrastructure in order to restore these essential services to facilitate community recovery. However, this is not to say that humanitarian and disaster relief missions cannot become complex—the existence of compounding external influences, such as political misalignment, resource constraints or destabilising security forces that seek to benefit from the unavailability of essential services, create a complex problem. It serves to highlight the value-adding that alternative planning processes, such as Design Thinking, can offer over traditional linear processes. Design Thinking offers a more flexible planning approach that is better suited to dynamic and complex problems, which is the problem set the ADF and its allies are almost certain to face in future conflict scenarios.[31]

Strengths of Design Thinking

Design Thinking and Design Thinking Behaviour have two key characteristics that could be integrated into the JMAP. Firstly, it offers a human-centric way to frame problems,[32] allowing continual consideration of how what is being created or planned will respond to human needs, which offsets the shortcomings of the COG focus of the JMAP. It enables more opportunities to develop creative options for how a problem can be solved, maximising flexibility for decision makers and reducing the likelihood of acting in a manner that is predictable and targetable by an adversary. Secondly, its focus on continual evaluation and adjustment enables more frequent contact with a complex adaptive system, and therefore enables a quicker OODA Loop.[33] The increased tempo of operational planning increases the probability of successful outcomes but affords more opportunities to interact and assess the impact of interactions on the adversary. With these interactions, more can be known about an adversary, and when combined with Strategic Empathy, pattern breaks can be identified. As Shore argues, pattern breaks ‘… can involve sudden spikes in violence, sharp reversal of policy, unexpected alternations to relations, or any substantial disruption from the norm’.[34] When pattern breaks are found, they can provide insightful clues as to what is driving an adversary to act, and can be critical in the Orient phase of the OODA Loop approach.[35] These are strengths that could assist in mitigating the downfalls of the existing JMAP’s linear, and arguably reductionist, approach.

Conclusion

It is clear that future complex and multidimensional warfare scenarios will demand a high level of agility and adaptability from the ADF that is beyond what has been required in recent warfare settings. The world is becoming increasingly complex, and the ADF may not have the luxury of entering a ‘war of choice’ as global geo-strategic competition increases.

This means an enhanced ADF planning approach is required, one that integrates elements of Design Thinking and Design Thinking Behaviour into the JMAP, particularly the Mission Analysis and Course of Action steps. This essay has explored the JMAP approach and compared it to Design Thinking. It discussed two key criticisms of the JMAP—the linear nature of the planning process, and the reductionist nature of the COG concept. It argued that a more adaptive, creative and rapid planning approach is required in order to maximise the opportunities to interact with a complex adaptive system, such as through the OODA Loop. It underscored the importance of learning from these interactions through a Strategic Empathy lens. Critically, military planners must provide flexible, scalable and adaptable options to the Australian government to ensure that military actions are aligned with political will. This is the most important aspect of integrated operational planning. It is, as Sun Tzu asserts, ‘strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat’.[36]

‘41 Great Military Leader Quotes Any Manager Can Learn From’, July 27, 2022. https://getlighthouse.com/blog/military-leader-quotes-manager-learn/.

Australian Army. ‘Accelerated Warfare’ | Australian Army Research Centre (AARC). Accessed October 24, 2023. https://researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/other/accelerated-warfare

Bogan, Mark E. ‘Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World’. The Army Lawyer 2015, no. 12 (December 2015): 39–43.

Christian, KM. ‘Cerebellum: Associative Learning’. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience, edited by George F. Koob, Michel Le Moal, and Richard F. Thompson, 242–48. Oxford: Academic Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-045396-5.00131-7

Clarke, Rachel Ivy. Design Thinking. Library Futures 4. Chicago: ALA Neal-Schuman, 2020.

Collins, Dominic, and Eamonn Treacy. ‘The Path towards Integrated Operations’. Tracking the Trends, 2021, 52–59.

Commonwealth of Australia. ‘Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process’, Edition 2. Directorate Publishing, Library and Information Services Joint Doctrine Directorate, August 2019.

Department of Defence. Australian Defence Force Warfare Training Centre. Website. Australian Government - Defence. Accessed October 29, 2023. https://www.defence.gov.au/education-training/education-providers/australian-defence-force-warfare-training-centre

Evans, Michael. ‘Forward From The Past: The Development Of Australian Army Doctrine, 1972-Present’ | Australian Army Research Centre (AARC). Accessed October 24, 2023. https://researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/land-warfare-studies-centre/forward-past-development-australian-army-doctrine-1972-present

Feickert, Andrew. ‘Defense Primer: Army Multi-Domain Operations (MDO)’. Congressional Research Service, November 2022. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/IF11409.pdf

Foster, Mary K. ‘Design Thinking: A Creative Approach to Problem Solving’. Management Teaching Review 6, no. 2 (June 2021): 123–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/2379298119871468

Harari, Yuval N. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. First US edition. New York: Harper, 2015.

Horbyk, Roman. ‘“The War Phone”: Mobile Communication on the Frontline in Eastern Ukraine’. Digital War 3, no. 1 (December 1, 2022): 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42984-022-00049-2

International Committee of the Red Cross. ‘Report: Protracted Conflict and Humanitarian Action’. September 6, 2016. https://www.icrc.org/en/document/protracted-conflict-and-humanitarian-action

Jackson, Aaron P. ‘Center of Gravity Analysis “Down Under”: The Australian Defence Force’s New Approach’. National Defense University Press. Accessed October 24, 2023. https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/1038829/center-of-gravity-analysis-down-under-the-australian-defence-forces-new-approach/

Kinni, Theodore. ‘The Critical Difference Between Complex and Complicated’. MIT Sloan Management Review, June 21, 2017. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-critical-difference-between-complex-and-complicated/

Krause, Michael. ‘Clausewitz and Centres of Gravity: Turning the Esoteric Into Practical Outcomes’. The Cove. Accessed October 28, 2023. https://cove.army.gov.au/article/clausewitz-and-centres-gravity-turning-esoteric-practical-outcomes

Kurtz, Cynthia F, and David J Snowden. ‘The New Dynamics of Strategy: Sense-Making in a Complex and Complicated World’. IBM Systems Journal 42, no. 3 (2003): 462.

Lind, Johan. ‘What Can Associative Learning Do for Planning?’ Royal Society Open Science 5, no. 11 (November 28, 2018): 180778. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.180778

Livieratos, Cole. ‘From Complicated to Complex: The Changing Context of War’. Modern War Institute, June 14, 2022. https://mwi.westpoint.edu/from-complicated-to-complex-the-changing-context-of-war/

McChrystal, Stanley A, Tantum Collins, David Silverman, and Chris Fussell. Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. New York, New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2015.

Mind Tools. ‘OODA Loops - Understanding the Decision Cycle’. Accessed October 24, 2023. https://www.mindtools.com/a3ldgz1/ooda-loops

Nations, United. ‘Addressing the Sustainable Urbanization Challenge’. United Nations. United Nations, June 2012. https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/addressing-sustainable-urbanization-challenge

Post, Ryan. ‘The Joint Military Appreciation Process: The Good, The Bad and Some Alternatives’. The Forge, 2022. https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2022/joint-military-appreciation-process-good-bad-and-some-alternatives

Razzouk, Rim, and Valerie Shute. ‘What Is Design Thinking and Why Is It Important?’ Review of Educational Research 82, no. 3 (September 2012): 330–48. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312457429

Shore, Zachary. A Sense of the Enemy: The High Stakes History of Reading Your Rival’s Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Smelser, Neil J. ‘Collective Myths and Fantasies’. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 11, no. 1 (1983): 1–15.

Spencer, John. ‘The Eight Rules of Urban Warfare and Why We Must Work to Change Them.’ Modern War Institute, January 12, 2021. https://mwi.westpoint.edu/the-eight-rules-of-urban-warfare-and-why-we-must-work-to-change-them/

Tomasello, Michael, Malinda Carpenter, Josep Call, Tanya Behne, and Henrike Moll. ‘Understanding and Sharing Intentions: The Origins of Cultural Cognition’. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 28, no. 5 (October 2005): 675–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X05000129

Tomasello, Michael, Alicia P. Melis, Claudio Tennie, Emily Wyman, and Esther Herrmann. ‘Two Key Steps in the Evolution of Human Cooperation: The Interdependence Hypothesis’. Current Anthropology 53, no. 6 (December 2012): 673–92. https://doi.org/10.1086/668207

Tzu, Sun. ‘Sun Tzu: Strategy without Tactics Is the Slowest Route to Victory. Tactics without Strategy Is the Noise before Defeat’. CTOvision.com. Accessed October 29, 2023. https://ctovision.com/quotes/sun-tzu-strategy-without-tactics-is-the-slowest-route-to-victory-tactics-without-strategy-is-the-noise-before-defeat/

United States Department of the Army. ‘Field Manual 100-5: Operations’. US Army Publishing Directorate, 1986. https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll9/id/893/

Understanding the Military Design Movement: War, Change and Innovation. Routledge Studies in Conflict, Security and Technology. London; New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2023.

Vowell, JB, and Craig Evans. ‘Operationalizing Strategic Empathy: Best Practices from Inside the First Island Chain’. The Strategy Bridge, November 16, 2022. https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2022/11/16/operationalizing-strategic-empathy

Zilincik, Samuel. ‘Why the “Fear, Honour and Interest” Trinity Harms Our Understanding of War’. The RUSI Journal 166, no. 2 (July 14, 2021): 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2021.1939771

Zweibelson, Ben. ‘Gravity-Free Decision-Making: Avoiding Clausewitz’s Strategic Pull’, Australian Army Research Papers; no. 8, December 2015.

1 ‘41 Great Military Leader Quotes Any Manager Can Learn From’, July 27, 2022, https://getlighthouse.com/blog/military-leader-quotes-manager-learn/.

2 Michael Evans, ‘Forward From The Past: The Development Of Australian Army Doctrine, 1972-Present’ | Australian Army Research Centre (AARC), accessed October 24, 2023, https://researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/land-warfare-studies-centre/forward-past-development-australian-army-doctrine-1972-present.

3 Cole Livieratos, ‘From Complicated to Complex: The Changing Context of War’, Modern War Institute, June 14, 2022, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/from-complicated-to-complex-the-changing-context-of-war/.

4 Evans, ‘Forward From The Past: The Development Of Australian Army Doctrine, 1972-Present’ | Australian Army Research Centre (AARC).

5 Aaron P. Jackson, ‘Center of Gravity Analysis “Down Under”: The Australian Defence Force’s New Approach’, National Defense University Press, accessed October 24, 2023, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/1038829/center-of-gravity-analysis-down-under-the-australian-defence-forces-new-approach/.

6 Dominic Collins and Eamonn Treacy, ‘The Path towards Integrated Operations’, Tracking the Trends, 2021, 52–59.

7 Department of Defence, ‘Australian Defence Force Warfare Training Centre’, Website, Australian Government - Defence, accessed October 29, 2023, https://www.defence.gov.au/education-training/education-providers/australian-defence-force-warfare-training-centre.

8 Commonwealth of Australia, Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, Edition 2 (Directorate Publishing, Library and Information Services Joint Doctrine Directorate, August 2019).

9 Yuval N Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, First US edition (New York: Harper, 2015).

10 Harari.

11 KM Christian, ‘Cerebellum: Associative Learning’, in Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience, ed. George F. Koob, Michel Le Moal, and Richard F Thompson (Oxford: Academic Press, 2010), 242–48,https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-045396-5.00131-7.

12 Johan Lind, ‘What Can Associative Learning Do for Planning?’, Royal Society Open Science 5, no. 11 (November 28, 2018): 180778,https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.180778.

13 Neil J Smelser, ‘Collective Myths and Fantasies’, Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 11, no. 1 (1983): 1–15.

14 Commonwealth of Australia, Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, Edition 2. Pg 15.

15 Mind Tools, ‘OODA Loops - Understanding the Decision Cycle’, accessed October 24, 2023,https://www.mindtools.com/a3ldgz1/ooda-loops.

16 Stanley A McChrystal et al, Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World (New York, New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2015).

17 Roman Horbyk, ‘“The War Phone”: Mobile Communication on the Frontline in Eastern Ukraine’, Digital War 3, no. 1 (December 1, 2022): 9–24, https://doi.org/10.1057/s42984-022-00049-2.

18 ‘Accelerated Warfare’ | Australian Army Research Centre (AARC), accessed October 24, 2023, https://researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/other/accelerated-warfare.

19 ‘Accelerated Warfare’ | Australian Army Research Centre (AARC).

20 United Nations, ‘Addressing the Sustainable Urbanization Challenge’,(United Nations, June 2012), https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/addressing-sustainable-urbanization-challenge.

21 John Spencer, ‘The Eight Rules of Urban Warfare and Why We Must Work to Change Them’, Modern War Institute, January 12, 2021, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/the-eight-rules-of-urban-warfare-and-why-we-must-work-to-change-them/.

22 International Committee of the Red Cross, ‘Report: Protracted Conflict and Humanitarian Action’, Report, September 6, 2016, https://www.icrc.org/en/document/protracted-conflict-and-humanitarian-action.

23 Ben Zweibelson, ‘Gravity-Free Decision-Making: Avoiding Clausewitz’s Strategic Pull’, Australian Army Research Papers; no. 8, December 2015.

24 United States Department of the Army, Field Manual 100-5: Operations, US Army Publishing Directorate, 1986, https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll9/id/893/.

25 JB Vowell and Craig Evans, ‘Operationalizing Strategic Empathy: Best Practices from Inside the First Island Chain’, The Strategy Bridge, November 16, 2022, https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2022/11/16/operationalizing-strategic-empathy.

26 Samuel Zilincik, ‘Why the “Fear, Honour and Interest” Trinity Harms Our Understanding of War’, The RUSI Journal 166, no. 2 (July 14, 2021): 10–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2021.1939771.

27 Rim Razzouk and Valerie Shute, ‘What Is Design Thinking and Why Is It Important?’, Review of Educational Research 82, no. 3 (September 2012): 330–48, https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312457429.

28 Mary K. Foster, ‘Design Thinking: A Creative Approach to Problem Solving’, Management Teaching Review 6, no. 2 (June 2021): 123–40, https://doi.org/10.1177/2379298119871468.

29 Razzouk and Shute, ‘What Is Design Thinking and Why Is It Important?’ Pg 331.

30 Theodore Kinni, ‘The Critical Difference Between Complex and Complicated’, MIT Sloan Management Review, June 21, 2017, https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-critical-difference-between-complex-and-complicated/.

31 Andrew Feickert, ‘Defense Primer: Army Multi-Domain Operations (MDO)’, Congressional Research Service, November 2022, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/IF11409.pdf.

32 Foster, ‘Design Thinking’.

33 Mind Tools, ‘OODA Loops - Understanding the Decision Cycle’.

34 Zachary Shore, A Sense of the Enemy: The High Stakes History of Reading Your Rival’s Mind (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

35 Mind Tools, ‘OODA Loops - Understanding the Decision Cycle’.”

36 ‘Sun Tzu: Strategy without Tactics Is the Slowest Route to Victory. Tactics without Strategy Is the Noise before Defeat’, CTOvision.com, accessed October 29, 2023, https://ctovision.com/quotes/sun-tzu-strategy-without-tactics-is-the-slowest-route-to-victory-tactics-without-strategy-is-the-noise-before-defeat/.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.