Introduction

This essay will show that Australia’s current Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) doctrine has limited applicability toDefence by arguing that the method by which Courses of Action (COA) are created throughout the Mission Analysis (MA) and COA-Development (COA-D) steps of the process limits creative thinking. Limitations on creative thinking in the creation of COAs are of direct relevance to the JMAP’s applicability as the Australian Defence Force (ADF) shifts focus towards an integrated, multi-domain approach to warfare, campaigns and operations.[1] The term ‘COA creation’ will be used in this paper to encompass all activities within the MA and COA-D Steps of the JMAP. The label ‘ADFP 5.0.1’ will be used to refer to the current JMAP doctrine to avoid confusion with the process itself.[2] The paper assumes that the reader has either familiarity with the JMAP or access to ADFP 5.0.1.

The idea that Australian military planning processes limit creative thinking is a common criticism and has been discussed by Walker and Jackson.[3] Restrictions on creative thinking is also a complaint from Zweibelson of Western military planning processes in general and the US planning processes in particular.[4] The US has sought to promote and implement design thinking in response.[5] The original aspect of this paper is that the cause of limiting creative thinking will be ascribed to the way in which COAs are created in Edition 2 AL3 of ADDP 5.0.1 as opposed to the JMAP as a whole or military planning processes in general.

Argument will be based on consideration of the current process for development of COAs. The only example used will be the fictional example scenario within ADDP 5.0.1 due to the lack of publicly available analysis of the JMAP’s use in real scenarios. Logical analysis will show that the existing method of creating COAs leaves a planning team with limited scope for creativity in a multi-domain and/or integrated context. This is due to an inherent rigidity in the JMAP created by switching from a top-down to bottom-up methodology during MA and delaying the consideration of integrated, multi-domain solutions for achieving the desired end state. The way in which COAs are created in ADDP 5.0.1 will be compared to the approach used by the Australian Border Force (ABF) and the creation of the Work Breakdown Structure from the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) Guide.

An amendment to ADDP 5.0.1 to solve the argued deficiency and therefore increase applicability in integrated, multi-domain scenarios will be discussed at the end of the paper and the possible disadvantage acknowledged. This option would require only minor amendments to the ordering and presentation of information within ADDP 5.0.1 and the provision of two different versions of the MA and COA-D steps. This approach would enable the JMAP to maintain a similar form and process to present to minimise the need to retrain Australian military planners.

This paper does come with several limitations. The idea for the argument originated from experiences in Joint Exercise (JEX) periods One and Two during the Australian Command and Staff Course with no prior experience with the JMAP or planning at the operational level. The scenarios in both those periods were in training environments, non-conflict, focused on events in the land domain and which had limited need to consider adversary action. The JMAP showed satisfactory applicability in those circumstances which suggests that it may have more utility and applicability in scenarios focused to a single domain (like recent Middle East operations) or ones that come with clear political or practical limits on the number and type of forces available (such as humanitarian assistance or other peacetime activities). Another limitation is that there is a lack of academic commentary and practitioner’s analysis to support the argument. This is assessed to be because linking the restriction of creative thinking to the COA creation process in Edition 2 appears to be a new argument within the public fora.

COA and the JMAP

ADDP 5.0.1 defines a course of action as ‘a possible plan that would achieve an objective or the desired end state’.[6] The process of COA creation begins in the early sub-steps of MA. The first part of the process is identifying the adversary’s Centre of Gravity (COG) and the constituent Critical Factors (CF).[7] The validity and interpretation of COG as a basis for military planning is hotly discussed in academia and amongst practitioners and will not be debated here. Meyer provides an excellent comparison of the prominent interpretations of the concept.[8] Such a concept also has primacy within the US, UK and NATO processes.[9] The debate is recognised within ADDP 5.0.1 and strong justification is provided for retaining the concept.[10]

The objectives of a campaign or operation are then created with reference to the desired end state determined in the first step of the JMAP, Scoping and Framing (S+F).[11] This process is deconstructive and is the planning team’s best representation of how to achieve the end state. To this stage the process has followed a logical top-down approach to planning, although based on a concept that attracts much debate. The methodology then switches to bottom-up. Planning teams next create a list of Decisive Points (DP) from consideration of the enemy’s CFs, our own CFs needing protection, or the list of essential tasks generated in previous sub-steps of MA.[12] A DP is:

‘A significant operational milestone that exists in time and space or the information domain which constitutes a key event, essential task, critical factor or function that, when executed or affected, allows a commander to gain a marked advantage, or contributes to achieving success.’[13]

The DPs are then sequenced to create a Line of Operation (LOO) associated with an objective. Each objective usually translates to at least one LOO but it is possible to have multiple objectives within one LOO.[14] Creation of DPs in this generic manner and their ordering to construct a LOO in support of objectives illustrates the shift to a bottom-up approach rather than continuing to work down by methodically decomposing the objectives into LOOs with directly related DPs. The outcome of the process to this point is a design schematic that is considered by the Commander for approval. The JMAP then moves to the COA-D step informed by the Commander’s thematic guidance on the development of COAs from the design schematic.

The label ‘COA-Development’ is somewhat misleading as the only development that occurs is assigning differing force composition and resources to each DP to achieve distinction between COAs.[15] The overall direction of the to-be developed COA has already been set. This is the inherent rigidity within the process. It might be noticed that all planning to this point has occurred without reference to how the capabilities of the five warfighting domains or non-military aspects of national power can be used and combined to achieve or influence the desired end state. In fact, ‘Exploitation of Domains’ is only a four-line paragraph in a chapter of 18 pages.[16] On face value it is logical to delay consideration of domains and capabilities until this point to ensure flexibility, but not if the reader considers the fundamental characteristics and differences between the domains from which these capabilities may belong.[17]

A good illustration is the example scenario used within the JMAP. Consideration of a maritime approach during COA-D results in six DPs being removed and one added to a LOO that only had 17 DPs to start with.[18] This suggests that either a maritime option was not suited to that LOO or that the DPs were conceived with thinking that had an amount of subconscious bias to one domain. Given that the other two COAs investigated land domain options and required no addition or deletion of DP, the latter appears likely. Creation, culling or adjustment of DPs during COA-D to match the capability domain may seem like a simple solution, but ADDP 5.0.1 discourages this to ‘maintain the integrity of the original design LOO’.[19] In the current JMAP, the underlying default mindset when developing COAs appears to be ‘how could units and capabilities be used to best achieve this effect’ rather than ‘what effects can the various domain capability options best provide and how might those be combined to achieve the desired end state?’ Earlier consideration of integrated, multi-domain capabilities to achieve the identified objectives may have produced better options. A continuation of the top-down methodology would have then ensured that the generated LOOs and DPs were relevant.

Other Planning Methodologies

A methodical process is still needed to create effective and well considered plans due to the complexity of military situations but this should not constrain the creative thought of planners by delaying the proposition of COAs. Development of COAs is an item which occurs relatively early in other planning processes. Major General Chris Field of the Australian Army and a former Commander Forces Command recognises it as an early step in his summation of Western military planning processes.[20] For the ABF, it’s the second step.[21] The creation of a Work Breakdown Structure within the PMBOK Guide doesn’t operate in terms of COAs like military planning but it does require early identification of the way in which a project will be subdivided and organised into its constituent parts.

ABF Operational Planning Framework

The ABF’s Operational Planning Framework implies a top-down planning methodology where COAs are proposed and developed early in the process. The ABF may seem like an organisation with an operating context of low variability compared to the ADF but this is not the case. The ABF operates in the land and maritime domains and must integrate with national and international organisations and agencies in their management of Australia’s borders and customs.[22] The ABF have a functionally similar definition of a COA to the ADF, ie courses of action frame how the directed result may be achieved’.[23] The ADF’s is ‘a possible plan that would achieve an objective or a desired end state’.[24] ‘Analyse’ is their first step and is very similar to the JMAP’s Scoping and Framing with several identical aspects and terminology. One major difference, however, is that one of the outputs from the step is to ‘propose viable, distinguishable, acceptable courses of action for further development by the planning staff in the Develop phase. These should be in broad outline only (e.g., a brief description of each course of action)’.[25] As shown, ADDP 5.0.1 doesn’t do this until the end of Step Three – COA-D. ‘Develop’ is the second step where the agreed COAs are developed in detail, including the capabilities required.[26] The way the COAs are detailed is not stipulated and no template is provided or referenced. The process implies that COAs for the ABF are concepts from which a plan is developed, whereas in the JMAP a COA is the result of plan development. Compared to JMAP, the ABF’s process has the benefit of allowing planners to consider possible solutions before producing detailed plans rather than compiling detailed documentary outputs from which a rigid design schematic emerges. The disadvantage relative to JMAP is that key aspects of the problem may be overlooked or considered in insufficient detail due to the apparent lack of detailed framing and analysis prior. A systematic and logical approach to detailing each COA can prove effective in mitigating that potential risk.

Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) Guide

The Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) as described in the PMBOK Guide is analogous to JMAP’s design schematic in that it ‘represents all product and project work’.[27] Its creation is also comparable, representing a combination of the MA and COA-D steps. Creating the WBS is described as ‘a hierarchical decomposition of the total scope of work to be carried out by the project team to accomplish the project objectives and create the required deliverables’.[28] The key word in this description is ‘decomposition’, which is a top-down process and is described as ‘a technique used for dividing and subdividing the project scope and project deliverables into smaller, more manageable parts’.[29] The strength of the top-down approach is that all subcomponents logically combine and link to the next higher level, the ‘100% rule’.[30] As shown from the JMAP example scenario, this is not always the case in the JMAP when DPs are created without consideration of the domains and capabilities that might be used.

Many methods can be used for creating the WBS structure depending on the situation. These structural distinctions are used to decompose the project into separate areas of work, comparable to objectives and LOOs. Such distinctions could be the phases of the project life cycle, the project’s major deliverables or incorporating elements developed by outside organisations such as contractors.[31] A bottom-up approach is also listed as providing a method to ‘group subcomponents’.[32] The distinction in relation to JMAP is worth considering. If DPs are likened to subcomponents in a bottom-up approach, the JMAP seeks to identify all subcomponents at the outset and then arrange them to work upwards towards the identified objectives. The use of a bottom-up approach in PMBOK seems to only have utility if some subcomponents are obvious at the outset but the way they contribute to the overall project is not.

A possible solution

The current method of creating COAs could be described as a thematic approach due to the Commander providing thematic guidance at the end of MA for COA-D. An alternative planning process in line with the arguments of this paper might be called an agnostic approach. In this method, the Commander would not provide thematic guidance to the team at any stage. The intent would be to explicitly require the team to brainstorm and present broad COAs, like the ABF, at the end of MA based on consideration of how multi-domain capabilities could be integrated to achieve victory. After approval by the Commander, each broad COA can then be successively decomposed, like the creation of the WBS in project management, into LOOs and then DPs before becoming detailed COAs. This approach would increase JMAP’s applicability by enabling creative thinking about integrated multi-domain options without radically altering the processes within the JMAP or compromising its other documentary outputs or inherent thoroughness.

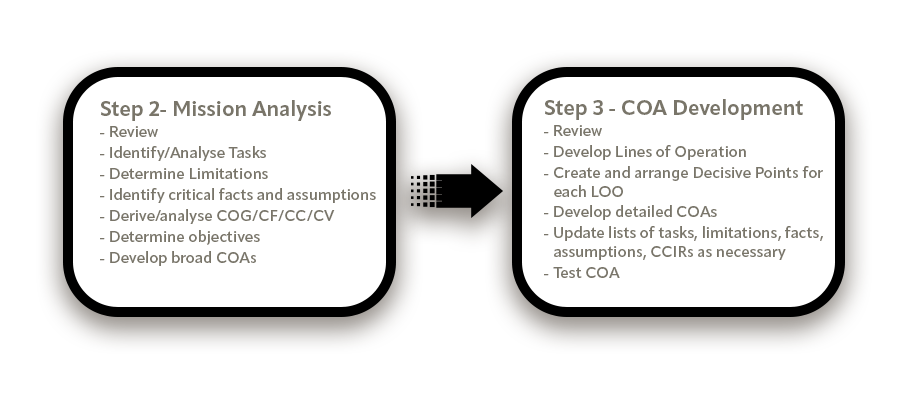

Achieving this would require several changes to ADDP 5.0.1 but could be achieved with minimal disruption to the workforce’s understanding. The first would be to reorder the presentation of the information within doctrine. The underlying concepts of operational planning would be explained first and would precede an explanation of each JMAP step. The function of each step would be described but without reference to the individual sub-steps. Secondly, the conduct and function of each sub-step would be described without reference to a particular step. Finally, the Thematic and Agnostic approaches would be presented diagrammatically to show how the sub-steps are grouped within each step. Steps 1, 4 and 5 would likely be identical to present in both approaches with the exception that the Commander would need to state, at the end of S+F, their direction for the Thematic or Agnostic approach thereafter. The MA and COA-D steps within the Agnostic approach could be presented as per Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Agnostic approach to JMAP Steps Two and Three

Afterwards, the conceptual and cognitive differences between the two methods would need to be presented for the reader’s awareness to avoid the Agnostic approach becoming the Thematic approach, but with initial direction to propose broad COAs at the end of MA. ADDP 5.0.1 currently does an excellent job of highlighting to the reader that the process is circular, not linear, and that creative thinking is necessary throughout. This would still be applicable and would need retention. Other aspects like continuously reviewing the operational situation for changes and ensuring continued alignment with the desired end state should also remain.

A disadvantage of this proposal would be a possible lack of detail and understanding of the situation prior to COA-D. This presents a risk of wasting time and effort developing COAs that are not well aligned to the problem. Addressing this perceived deficiency was a stated aim of Edition 2 and is why the MA step in ADDP 5.0.1 is significantly larger than the previous edition.[33] This risk may, however, be an unavoidable part of a planning process that has satisfactory applicability in multi-domain, integrated scenarios. The culture, experience and professionalism of the planning team and the oversight of the Commander and key planners may be the appropriate mitigation measure.

Conclusion

This essay has argued that creative thinking is restricted in the current JMAP and that this is a result of the way in which Courses of Action are created through the Mission Analysis and COA-Development steps of the process. It has also argued that this means that the JMAP is poorly suited to considering integrated, multi-domain options and that it therefore has low applicability to the ADF given the current direction on integrated, multi-domain approaches to warfare, campaigns and operations.

It has been shown that MA produces a rigid, generic design schematic for military operations that constrains the ability of planning teams to integrate multi-domain capabilities to create distinguishable COAs when assignment of forces is considered in COA-D. This was ascribed to a combination of switching between top-down and bottom-up methodologies and delaying the consideration of multi-domain options until COA-D. Review of the example scenario within ADDP 5.0.1 showed that this resulted in a design schematic with Decisive Points that were not suited to a particular domain and required substantial adjustment because the characteristics of the various domains, and the opportunities that multi-domain capabilities presented, had not been considered earlier in the process.

The JMAP was compared to the Operational Planning Framework of the Australian Border Force and the process of creating a Work Breakdown Structure from the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) Guide. Both use top-down methods and consider possible solutions much earlier in the process compared to the JMAP. The ABF’s approach proposes broad COAs during the first planning step which are subsequently developed into detailed options. The PMBOK’s approach was shown to be comparable to COA creation, despite contextual differences, and used a thorough process whereby the approach to a project is decided at the outset and the entire work scope is then identified through logical decomposition into successive levels.

Finally, an amendment proposal to JMAP was provided to rectify the issues identified and enable more creativity when planning. It was proposed that Commanders, early in the process, direct that their planning staff follow either the current process or a modified process whereby the sub-steps of MA and COA-D are different. The current process was labelled ‘thematic’ and the new ‘agnostic’. The Agnostic approach would require planners to devise and propose broad COAs during MA which could then be considered by the Commander for development in COA-D. The necessary changes to the presentation of information within ADDP 5.0.1 was also discussed as well as a possible disadvantage to this proposal. Such a change would reduce the rigidity of the JMAP and increase its applicability to Defence by enabling creative consideration of integrating multi-domain capabilities to achieve operational end states.

Australia, Commonwealth of. ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations. Canberra, Australia: Lessons and Doctrine Directorate, 2021.

Australia, Commonwealth of. ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process. Canberra, Australia: Directorate Publishing, Library and Information Service, 2019.

Force, Australian Border. Operational Planning Framework: Australian Government, 2022.

Defence, Department of. Integrated Campaigning. Canberra, Australia: Department of Defence, 2022.

Defence, UK Ministry of and NATO. Allied Joint Publication - 5 Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations. United Kingdom: Ministry of Defence, 2021.

Field, Major General Chris. ‘Five Ideas: On Planning’. The Cove, Australian Army, accessed October 23, 2023, https://cove.army.gov.au/article/five-ideas-planning

Institute, Project Management. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge. Sixth ed. Newton Square, Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, 2017. https://eds.s.ebscohost.com/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzE1OTUzMjFfX0FO0?sid=37830749-e04a-4923-8601-396104328a22@redis&vid=0&format=EK&rid=10

Jackson, Dr Aaron P. ‘Three Simple Ways to Make the Military Appreciation Process More Creative’. The Cove, Australian Army, accessed October 16, 2023. https://cove.army.gov.au/article/three-simple-ways-make-military-appreciation-process-more-creative

Meyer, Eystein L. ‘The Centre of Gravity Concept: Contemporary Theories, Comparison, and Implications’. Defence Studies 22, no. 3 (2022/07/03 2022): 327-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2022.2030715

Staff, Joint Chiefs of. Joint Publication 5-0 Joint Planning. United States: Joint Force Development, 2020.

Walker, Captain David L. ‘Refining the Military Appreciation Process for Adaptive Campaigning’. Australian Army Journal 3 (2011): 85-100. https://researchcentre.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/aaj_2011_2.pdf

Zweibelson, Ben. ‘Seven Design Theory Considerations’. Military review 92 (2012): 80-89. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20121231_art013.pdf

1 Department of Defence, Integrated Campaigning (Canberra, Australia: Department of Defence, 2022), 8-9.

2 The current version is ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process Edition 2 AL 3. Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process Edition 2 AL 3 (Canberra, Australia: Directorate Publishing, Library and Information Service, 2019).

3 Captain David L Walker, ‘Refining the Military Appreciation Process for Adaptive Campaigning’, Australian Army Journal 3 (2011): 85-100, https://researchcentre.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/aaj_2011_2.pdf;

Dr Aaron P. Jackson, ‘Three Simple Ways to Make the Military Appreciation Process More Creative’, The Cove, Australian Army, 2023, https://cove.army.gov.au/article/three-simple-ways-make-military-appreciation-process-more-creative

4 Ben Zweibelson, ‘Seven Design Theory Considerations’, Military Review 92 (2012): 82,https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20121231_art013.pdf

5 Captain David L Walker, ‘Refining the Military Appreciation Process for Adaptive Campaigning’, 96.

6 Commonwealth of Australia, Glossary, ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process Edition 2 AL 3 (Canberra, Australia: Directorate Publishing, Library and Information Service, 2019), iii.

7 Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1, 3–6 - 3–14.

8 Eystein L Meyer, ‘The Centre of Gravity Concept: Contemporary Theories, Comparison, and Implications’. Defence Studies 22, no. 3 (March 2022): 327-53, https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2022.2030715

9 Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 5-0 Joint Planning (United States: Joint Force Development, 2020), III-37; UK Ministry of Defence and NATO, Allied Joint Publication - 5 Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations (United Kingdom: Ministry of Defence, 2021), 3–9.

10 Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1, 3–7.

11 Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1, 3–21.

12 Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1, 3–37.

13 Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1, 3–33.

14 Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1, 3–21.

15 Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1, 4–6.

16 Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1, 4–10.

17 Commonwealth of Australia, ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations (Canberra, Australia: Lessons and Doctrine Directorate, 2021), 27-31.

18 Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1, 4–16.

19 Commonwealth of Australia, ADFP 5.0.1, 4–6.

20 Major General Chris Field, ‘Five Ideas: On Planning’, The Cove, Australian Army, 2018, accessed October 23, 2023, https://cove.army.gov.au/article/five-ideas-planning.

21 Australian Border Force, Operational Planning Framework (Australian Government, 2022), 16.

22 Australian Border Force, Operational Planning Framework, 2.

23 Australian Border Force, Operational Planning Framework, 16.

24 Commonwealth of Australia, Glossary, ADFP 5.0.1, iii.

25 Australian Border Force, Operational Planning Framework, 15.

26 Australian Border Force, Operational Planning Framework, 16.

27 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge. Sixth ed (Newton Square, Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, 2017), https://eds.s.ebscohost.com/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzE1OTUzMjFfX0FO0?sid=37830749-e04a-4923-8601-396104328a22@redis&;vid=0&format=EK&rid=10, 161

28 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 157.

29 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 158.

30 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 161.

31 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 159.

32 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 159.

33 Commonwealth of Australia, Preface ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process Edition 2 AL 3 (Canberra, Australia: Directorate Publishing, Library and Information Service, 2019), iv.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.