Introduction

As described in the Defence Strategic Review, the ADF is facing a strategic environment that is increasingly complex. Potential adversaries are operating across multiple domains within adaptive systems that integrate soft power with traditional military capabilities to achieve a range of objectives. To impose maximum impact on the Operating Environment (OE) across the spectrum of conflict, the ADF needs to plan for adaptive operations across all domains and through all dimensions.[1] The Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) is the ADF’s planning tool used to orchestrate operations across the traditional physical domains of land, maritime, and air. Recently, warfare has seen the introduction of additional domains: Space,[2] the electromagnetic spectrum (EMS), human, information, and cyber.[3] Operations across these expanded domains are termed multi-domain operations (MDOs).

However, operational planning in the ADF has tended toward concurrent single-domain operations focused on domain capabilities rather than integrated operations across domains and dimensions that focus on desired effects.[4] The JMAP and its associated intelligence process, the Joint Intelligence Preparation of the Operating Environment (JIPOE), take a stovepiped approach to friendly force and adversary analysis that is not suited to integrating complex operational effects across multiple domains in space and time. These processes are also iterative and linear, stifling agility. There are other planning frameworks that better integrate effects across domains, from which the ADF can draw lessons.

The Joint Targeting Cycle (JTC) is one such framework. The JTC executes the plans arising from the JMAP and is a complementary planning process. It is used by the ADF to synchronise joint force kinetic and non-kinetic effects[5] for MDOs. In contrast to the JMAP and JIPOE, the JTC and its supporting intelligence process, Target Intelligence, deliberately take a systems view of the OE, the adversary, and joint force capabilities.[6] It is also not linear and includes sub-processes for rapid adaptation to evolving circumstances. It considers the OE as an integrated and adaptive system of systems, within which joint capabilities are an interrelated web that can cause synchronised or convergent effects as required.

This paper will argue that the JMAP and the JIPOE should adopt an adaptive systems approach to MDOs to meet the challenge of a complex and adaptive adversary. It will first define MDOs and then will analyse the JMAP’s approach to operational planning across multiple domains. It will draw comparison with how the JTC enables adaptive effects-centric MDOs through a systems approach as an example process planners can use for inspiration to improve the JMAP.

Adaptive MDOs and effects-centric warfare

MDOs provide the ‘convergence of capabilities across domains, environments and functions in time and spaces’[7] to achieve common objectives against complex targets. This convergence of effects is based on the understanding that no singular domain can operate to full effectiveness without the others.[8] Focusing operational objectives on convergent effects, also known as ‘effects-centric warfare’, promotes planning that considers the desired holistic outcome without being driven by singular domain capabilities. Effects-centric warfare allows the ADF to achieve asymmetric advantage by applying a combination of effects against adversary vulnerabilities, the aggregation of which is greater than the sum of its parts. This requires the ability to manoeuvre concurrent effects seamlessly through all domains.[9]

MDOs are not synonymous with ‘joint’ operations. In the ADF, joint operations typically include the physical domains of land, maritime and air, which are traditionally the remit of the Australian Army, Navy, and Air Force, respectively. This approach does not result in convergent effects across multiple domains; instead, they result in operations within each domain concurrently to achieve multiple objectives that may be mutually supporting, but are not integrated, to achieve maximum effect against the adversary system.

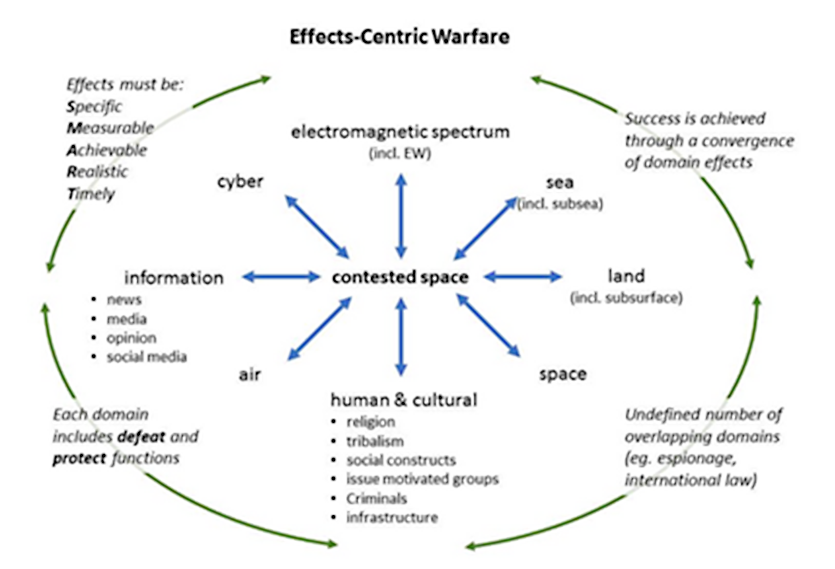

Although there is no consensus among nations on the domains that comprise MDOs, most definitions include at least land, sea, air, cyber, Space, information (sometimes including EMS and Electronic Warfare (EW)), and the human (social/cultural/cognitive) domains. These domains and their relationship to ‘effects’ are represented in Figure 1.[10]

Figure 1. Domains in Effects-Centric Warfare.

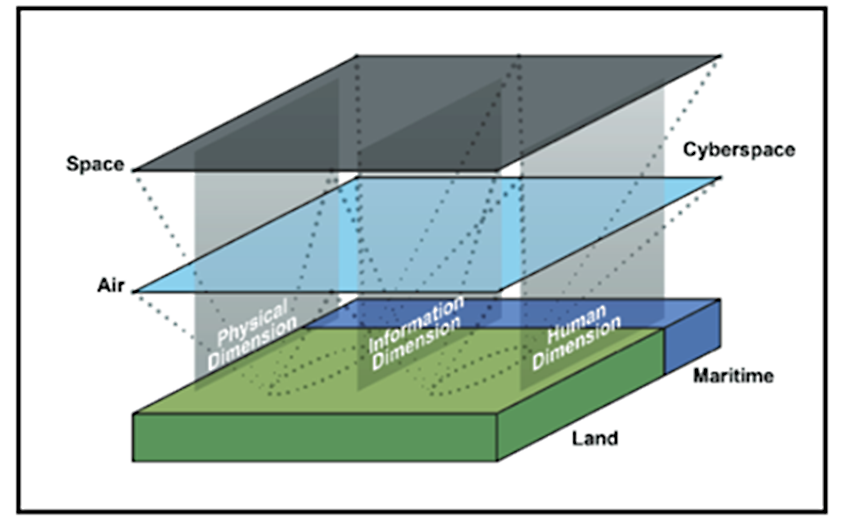

In the United States Army, MDOs are defined across five domains and three dimensions (Figure 2).[11] Manoeuvre and the deployment of effects occur in land, maritime, air, Space and cyber domains across the physical, information and human dimensions.

Figure 2. The Domain and Dimension relationship.

These concepts are consistent with ADF doctrine, which describes domains as ‘overlapping and interrelated physical and non-physical’.[12] In its simplest sense, land effects, such as destruction of an adversary Command and Control (C2) node, may occur from an air, maritime, or land platform in the physical dimension (eg, dropping bombs on a HQ compound). It may also mean that a destructive effect against an adversary C2 node, delivered by an air platform, may be supported by space denial effects in the information dimension (EW) to suppress adversary air defences around that node to enable access. The human dimension may be simultaneously influenced through the cyber domain via messaging to the military population about the abilities of adversary leadership to protect that C2 capability, undermining leadership’s credibility. Concurrently, cyber effects across the information dimension degrading access to critical C2 communications networks could reinforce this messaging. The convergence of these effects across domains and dimensions enables operations and maximises the overall effects on the entire adversary system.

MDOs work well in theory for asymmetric advantage. However, as the ADF may use this approach against a complex and adaptive environment, it must be applied in coordination with a systems approach.[13] Systems thinking recognises that the parts of a system, how they operate and how they will adjust under external stimuli can only be understood within the ‘context of the larger whole’.[14] If one part of the system changes, the rest will also change. In MDOs, where militaries seek to apply convergent effects against the adversary, this may prompt changes across many other interconnected parts of the OE system. To appreciate the potential desired and undesired outcomes resulting from MDOs, and be prepared for possible contingencies, planning and intelligence staff in the Joint Planning Group (JPG)[15] must seek to understand the OE as an adaptive system across all domains and through all dimensions. The current format of the JMAP does not promote this type of thinking.

JMAP and MDOs

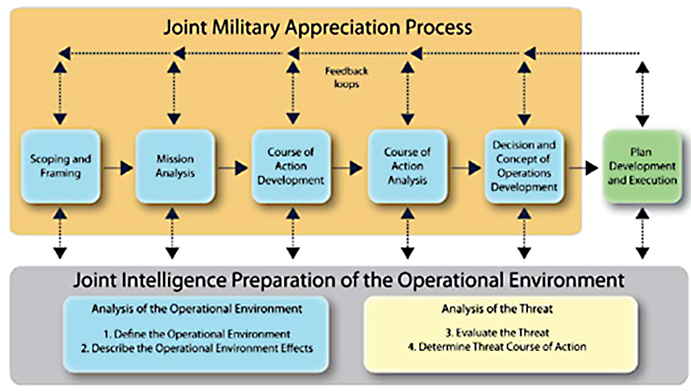

The ADF uses the JMAP as a framework for planning military operations, supported by intelligence via the JIPOE (Figure 3). However, due to its linearity, reductionism, and focus on capabilities over effects, the JMAP does not adequately support an MDO approach.

Figure 3. The JMAP and its relationship with JIPOE.[16]

Although the JMAP is not intended to be dogmatically applied—indeed, the doctrine states at the outset that it is ‘not supposed to be used as a formulaic checklist’[17]—the presence of aide memoirs and the step-by-step nature of the publication leads inexperienced practitioners to use it as such. The framework relies on planners applying the ‘operational art’ to bring creativity and experience to the planning process. This ‘art’ is highly subjective and depends on experienced planners who can appreciate the entirety of the OE, the adversary, and range of friendly force capabilities.[18] Arguably, within the context of a modern military, one would be hard-pressed to find one such individual in the right position at the right time to conduct effective planning for a specific operation, let alone a team. This results in a tendency for planners to approach the doctrine dogmatically as a checklist.[19]

After the first step, Scoping and Framing, the subsequent steps of the JMAP build on each other through an iterative and often reductionist thread of logic, where if a step or output is missed or is based on faulty assumptions, it risks compromising the subsequent outputs.[20] Although the doctrine encourages practitioners to revisit their assumptions periodically to confirm their thread of logic stays true,[21] time constraints and inherent biases, such as retrievability bias and anchoring, make this difficult in practice. Retrievability bias is the tendency for comparable events in the past to be used as predictors of the future, with minimal appreciation of the variability between circumstances. Anchoring is the tendency for a person to resist adjustment to their initial appraisal of a situation despite additional or different information. In combination, these forms of cognitive bias risk the assumption that past events indicate future eventualities and may cause practitioners to resist adjusting their initial ideas over time.[22] In the conduct of the JMAP, unless deliberately acknowledged and countered, these tendencies risk flawed outcomes in complex and adaptive situations.

This linearity and inherence for bias is most prevalent in the Mission Analysis step of the JMAP. For an operation against an adversary military, the JPG will identify adversary and friendly forces’ Centres of Gravity (COG). COG is ‘the prime entity that will either stop the friendly force from achieving its desired end state; or that which the adversary requires to achieve its end state.’[23] It provides a focus for friendly force protection and an aim point against the adversary. The JPG will also determine the friendly force mission objectives as they relate to the Commander’s Guidance from the previous step. Through iterative subsequent steps, these two elements (COG and objectives) become Decisive Points (DPs) that describe desired effects in the battlespace. Subsequent planning steps that eventuate in Task Orders (TASKORD) to Force Elements (FEs) follow directly from these outputs. This approach works well when the defeat of the adversary COG is the desired end-state. However, it doesn’t work well if the defeat of the COG is not the objective[24] or in less-than-warlike operations such as disaster relief, combat against non-traditional threats[25] or combating ‘competition’.[26] This linear thread of logic risks planning outputs if analyses of the COG and objectives are flawed at the outset.

Additionally, adversary and friendly force COGs exist within complex and adaptive systems. Once affected, the system changes to accommodate the degradation of what was previously the COG or shifts to protect the COG if the desired effect is not achieved. Over the life of the operation, the system will adapt so that the COG identified in the early steps of the planning process may no longer be a COG at later stages of the operation. The linear process of the JMAP induces an assumption that the COG identified at the start of planning will remain extant throughout, not considering the adaptability of the adversary as a complex system.[27]

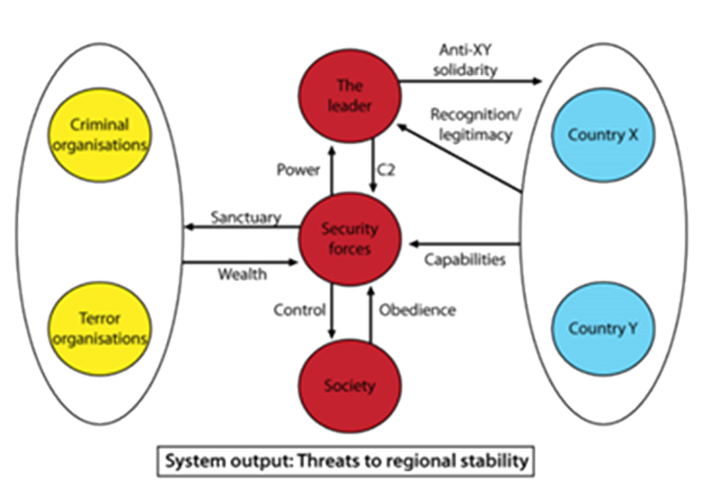

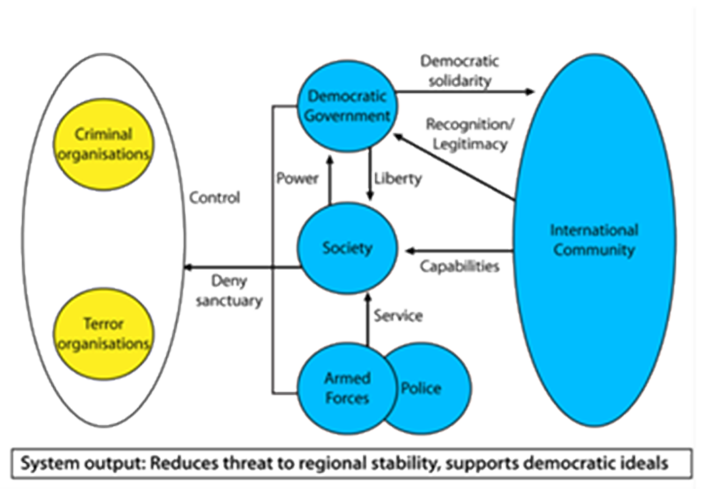

The planning doctrine acknowledges this complexity, stating ‘It is … understood that contemporary military operations are also interactively complex’ and that planners should seek to understand actors and relationships within a ‘complex adaptive system’.[28] However, despite this identification, the steps of the JMAP are linear and iterative. Within the ‘Framing’ sub-step of the first step of the JMAP, the OE is characterised in fixed terms as both an observed and a desired system (Figures 4 and 5).[29]

Figure 4. Actor relationships within the observed system (example).

Figure 5. Actor relationships within the desired system (example).

These models characterise the OE as it exists during planning and identify the interrelationships between stakeholders within the OE. Planners then characterise the desired OE so the JPG can identify the conditions for movement from the observed state to the desired state. These conditions help identify objectives and lead directly to DPs and Lines of Operation (LoO). However, this depiction of the OE in a fixed state does not account for the fluidity of complex adaptive systems. It assumes that affecting the relationships between elements of a system will cause the desired change. The doctrine does not guide practitioners to identify system interdependencies, redundancies, or resiliency, and does not direct practitioners to identify the consequences of these effects on the elements within the system over time. Therefore, subsequent actions throughout the operation may assume that the system remains largely unchanged.[30]

The JMAP is also supported by inputs from the friendly force components, primarily in the ‘Framing’ phase of the first step. In this phase, the friendly force analyses the initial capabilities available to the Joint Force.[31] Because the Joint Force will comprise contributions from each of the Services—Navy, Army and Air Force—it is natural for planners to define the friendly force contribution by Service rather than by the effect required.[32] This approach is reinforced in the second step, Mission Analysis, as the doctrine leads practitioners to define friendly force capabilities in terms of ‘Force Element’ (FE), which is a ‘component of a unit, a unit, or association of units having common objectives and activities’,[33] often within the same service. Friendly force contributions are defined by the capabilities they provide, not by the effect they will generate. At this early stage in the process, considering the friendly force contribution in terms fixed by Service confirms a cognitive framework that prioritises separate domain effects by available capability rather than the most applicable integrated MDO effects for operational objective success.

JMAP and the JIPOE

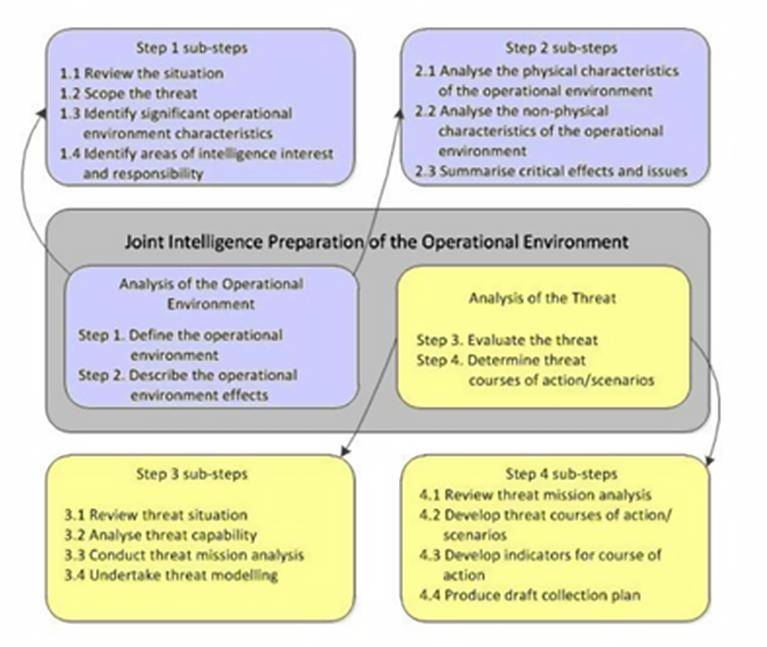

The JIPOE, intelligence input to planning, reinforces the JMAP’s linear and stovepiped perspective. The JIPOE is both a compilation of structured analytic techniques and a component of the planning process and consists of four steps (Figure 6). It provides estimative intelligence regarding the OE and should provide adequate situational awareness, so planners can approach the OE from a systems perspective.[34]

Figure 6. The JIPOE.[35]

However, the JIPOE neither views the adversary as a system nor acknowledges the complex and adaptive properties of the broader environmental system in which the adversary resides. The first step is entirely devoted to analysis of the OE. In the doctrine, analysts divide the threat Order of Battle (ORBAT) into domains for analysis—air, land, maritime, space, human, and information (including cyber and EMS). Dividing the threat into domain-specific capabilities early in the intelligence process cognitively biases both intelligence analysts and planners to consider the effects these capabilities generate in stovepiped terms.

In the third step, the JIPOE analyses the threat capabilities and capacity to affect Joint Force operations.[36] As steps one and two have already divided the threat into domain specific ORBAT, it is natural for step three to continue along this thread of logic, not only analysing each domain’s ability to affect the friendly force but also considering the possible vulnerabilities of each singular domain to friendly force capabilities. This approach to analysing the threat risks overlooking interdependent and adaptive complexities within the OE and risks biasing practitioners into matching domain capabilities in a stovepiped manner rather than conducting convergent MDOs.

JTCs and MDOs

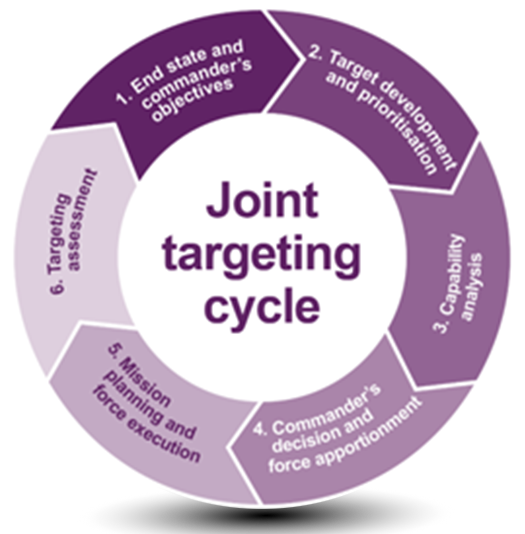

By contrast, targeting as a function in the ADF is considered within a ‘Full Spectrum’ planning framework operationalised by the JTC. This framework is designed to ‘integrate cyber, [S]pace, electronic warfare, information activities and strategic communications’ to meet the demands of a complex OE. It is used at the operational level to ensure the application of effects against adversary systems is efficient, lawful, and integrated. Because it considers the OE as a system at the outset and takes an effects-centric view of both friendly force and adversary capabilities, it offers a better framework for approaching complex and adaptive MDO. It consists of six steps (Figure 7).[37]

Figure 7. The Joint Targeting Cycle.

Like the JMAP, the JTC analyses the Commander’s Guidance and objectives in step one. The JTC’s first subsequent planning step (Target Development) is intelligence analysis of the OE system through the Target Intelligence process. In contrast to the JMAP,[38] no other planning commences until the intelligence process has provided an overarching view of the adversary system.

Target Development begins with Target Systems Analysis (TSA). This process is an all-source[39] intelligence activity that breaks the adversary system into its components and relationships. It identifies adaptive mechanisms and redundancies that allow the system to respond to external pressures within these relationships. From this systems-level view, analysts identify targetable entities that will provide maximum effect against the target system. Notably, Target Development is domain- and capability-agnostic—it considers all targetable entities across the range of domains and dimensions for vulnerability to effect, regardless of available capabilities at the time.[40] This means that the effects that are identified by analysts for action against the adversary are considered holistically within the framework of effects-centric warfare and MDOs, not in terms of domain or service.

The design of the JTC ensures this capability agnostic systems view is carried through the subsequent steps. Step three, Capabilities Analysis, considers the target vulnerabilities and effects identified within step two alongside capabilities available to the Joint Force. Analysts assess these capabilities for their combined abilities to achieve the desired impact on the adversary system. Only after this are the targets and objectives assigned to applicable FE, apportioning assets in a convergent way to achieve desired effects. These effects are specifically aimed at the target’s vulnerabilities to achieve results against the holistic adversary system. Critically, within this step is the explicit requirement for an ‘outcomes estimate’, where practitioners predict the range of outcomes the selected effects may have on the adversary system and OE. This estimate includes estimated recuperation and adaptation measures and intended and unintended consequences of the effect.[41] This process ensures that the efficacy of each target is evaluated within the context of the adversary system, ensuring the right effects are deployed against the right parts of the system. Most importantly, this step occurs before the Commander decides on the appropriate course of action for assigned FE, forcing practitioners to revisit their biases, address their assumptions, and ensure the plan is suitable for the circumstances at the time.

Conclusion

Although the JMAP includes many reminders to revisit assumptions and to consider the OE holistically, it does not address the complexity of the current OE or an adaptive adversary through MDOs. Instead, JMAP is doctrinally linear and promotes stovepiped application of service-based platforms to meet domain-specific operations. The doctrine will likely be followed dogmatically by practitioners given the level of experience and the amount of time ordinarily available to planning, limiting the ability of planners to bring together a convergence of effects to multiply the overall effect on the adversary system. The iterative nature of the doctrine also promotes retrievability bias and anchoring, which can prevent the challenging of assumptions, particularly as planning progresses and the assessments and decisions made early in an operation need to change. This approach is particularly risky if the adversary is not analysed within the framework of systems thinking, enabling the identification of adaptation and redundancy elements that may mitigate the success of effects brought against it.

The intelligence input to the JMAP, the JIPOE, also reinforces this view. It also analyses the adversary in domain-specific terms then considers the adversary vulnerabilities against comparable domain-specific friendly force capabilities. This input to the JMAP only serves to reinforce stovepiped allocation of FE, further restricting the convergence of effects across domains.

In contrast, the JTC is designed from its earliest planning stage to view the adversary as a system and as part of a broader environment system. Intelligence input to the JTC is fully integrated within the process and leads an assessment of the adversary’s system. This process codifies identification of vulnerabilities without consideration for domain, only in terms of the effects the target system is vulnerable to. This assessment is then further developed by analysis of friendly force capabilities that can achieve these effects in a convergent manner. Critically, including an ‘outcomes estimate’ before a Commander’s decision and issuing of orders forces planners to reconsider their biases and the validity of their plan to achieve the desired objectives.

The JMAP and the JIPOE could learn from the established practice of the JTC. Given that all three processes are owned and operated by the ADF, translating these concepts between doctrinal publications and processes should be relatively straightforward.

Department of Defence. Integrated Campaigning. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2022.

Department of Defence. ADF-I-3 Targeting. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023.

Department of Defence. ADF-P -2 Intelligence Ed 4. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021.

Department of Defence. ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021.

Department of Defence. ADF-P-5 – Planning. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021.

Department of Defence. ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process. Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, 2019.

Department of Defence. Defence Strategic Review. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023.

Griggs, Ray. ‘Building the Integrated Force’, The Strategist. June 07, 2017. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/building-integrated-joint-force/

Hlavizna, Petr and Vasicek, Radovan. The Role of Joint Intelligence Preparation of the Operating Environment in Support of Future Military Operations, S&T. STO-MP-IST-190: 2014, 3-1 – 3-8.

Jackson, Aaron P. Centre of Gravity Analysis “Down Under”: The Australian Defence Force’s New Approach. The Forge JFQ 84, 2017. 81-85.

https://theforge.defence.gov.au/sites/default/files/adfwtc02_aaron_jackson_-_c_of_g_analysis_down_under.pdf

Manolache, Ionela Catalina. ‘The Role of Multi-Domain Operations in Modern War’. Revista Acedemiei Fortelor Terestre, Vol. 28, Issue 3, 2023. 163-170. DOI: 10.2478.

Mella, Piero. Systems Thinking: Intelligence in Action. Italy: Springer Milano, 2012. DOI 10.1007/978-88-470-2565-3_1.

Pembroke, Paul. Synchronising Multidomain Operations Using the Breach Mindset, The Cove. 2019. https://cove.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/synchronising_multi_domain_operations_using_the_breach_mindset.pdf.

Post, Ryan. The Joint Military Appreciation Process: The Good, the Bad, and Some Alternatives, The Forge. 2022. https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2022/joint-military-appreciation-process-good-bad-and-some-alternatives

Scott, Trent. The Lost Operational Art: Invigorating Campaigning into the Australian Defence Force, Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre. 2011.

Selman, Jason. Effects-Centric Warfare: Across the spectrum of conflict, The Cove. June 24, 2019. https://cove.army.gov.au/article/effects-centric-warfare-across-spectrum-conflict

Tinker, Leigh. Flexibility is the Key to Tackling Contemporary Political Warfare, The Forge, 2021. https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2021/flexibility-key-tackling-contemporary-political-warfare

United States Department of the Army. FM 3-0 Operations. Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2022. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN36290-FM_3-0-000-WEB-2.pdf

Williams, Blair S. ‘Heuristics and Biases in Military Decision Making’, Military Review 90, no. 5, September 09, 2010. 58-70. Heuristics and Biases in Military Decision Making (army.mil)

1 Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review, (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023): 3-6, 71.

2 This paper will use a capital ‘S’ to delineate between the ‘Space’ domain, meaning the near vacuum that exists between planets and stars, and the term ‘space’, meaning the physical third dimension in which all things exist and move.

3 Department of Defence, ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations, (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021), 27-28.

4 Paul Pembroke, Synchronising Multidomain Operations Using the Breach Mindset, The Cove, 2019, https://cove.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/synchronising_multi_domain_operations_using_the_breach_mindset.pdf, 2.

5 ‘Kinetic’ refers to capabilities that use “forces of dynamic motion/energy to achieve an effect.” The term ‘effects’ refers to the application of something to create change across the range of domains, including cyber, space, cognitive (affecting decision-making), information, and kinetic (Department of Defence, ADF-I-3 - Targeting, (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023): 101).

6 Department of Defence, ADF-I-3 - Targeting, 28.

7 Petr Hlavizna and Radovan Vasicek, The role of Joint Intelligence Preparation of the Operating Environment in Support of Future Military Operations, S&T, STO-MP-IST-190:2014, 3-5.

8 Ionela Catalina Manolache, “The Role of Multi-Domain Operations in Modern War”, Revista Acedemiei Fortelor Terestre, Vol. 28, Issue 3, 2023, 166, DOI: 10.2478.

9 Department of Defence, Integrated Campaigning, (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2022): 20.

10 Jason Selman, Effects-Centric Warfare: Across the spectrum of conflict, The Cove, June 24, 2019, https://cove.army.gov.au/article/effects-centric-warfare-across-spectrum-conflict.

11 United States Department of the Army, FM 3-0 Operations, (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 2022): x, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN36290-FM_3-0-000-WEB-2.pdf.

12 Department of Defence, ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations, 27.

13 Ryan Post, The Joint Military Appreciation Process: The Good, the Bad, and Some Alternatives, The Forge, 2022,https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2022/joint-military-appreciation-process-good-bad-and-some-alternatives.

14 Piero Mella, Systems Thinking: Intelligence in Action, (Italy: Springer Milano, 2012): 1, DOI 10.1007/978-88-470-2565-3_1.

15 The Joint Planning Group is responsible for planning military operations, usually chaired by the planning staff and is typically attended by key representatives from all stakeholders across the ADF and other government agencies (Department of Defence, ADF-P-5 – Planning, (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021): 113).

16 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021): 1-2.

17 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 1-2.

18 Leigh Tinker, Flexibility is the Key to Tackling Contemporary Political Warfare, The Forge, 2021, https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2021/flexibility-key-tackling-contemporary-political-warfare.

19 Trent Scott, The Lost Operational Art: Invigorating Campaigning into the Australian Defence Force, (Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre, 2011): 34, 102.

20 Trent Scott, The Lost Operational Art, 41.

21 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 2-20.

22 Blair S. Williams, "Heuristics and Biases in Military Decision Making," Military Review 90, no. 5, September 09, 2010, 60, 66, Heuristics and Biases in Military Decision Making (army.mil).

23 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 3-6.

24 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 3-22.

25 Such as terrorist networks, insurgencies, or in stabilisation operations.

26 Aaron P. Jackson, Centre of Gravity Analysis “Down Under”: The Australian Defence Force’s New Approach, The Forge JFQ 84, 2017, 83, https://theforge.defence.gov.au/sites/default/files/adfwtc02_aaron_jackson_-_c_of_g_analysis_down_under.pdf.

27 Post, The Joint Military Appreciation Process.

28 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 2-11 – 2-12.

29 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 2-14 – 2-15.

30 Trent Scott, The Lost Operational Art, 24.

31 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 2A-1.

32 Ray Griggs, “Building the Integrated Force”, The Strategist, June 07, 2017, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/building-integrated-joint-force/.

33 Department of Defence, ADF-P-5 – Planning, 129.

34 Department of Defence, ADF-P -2 Intelligence Ed 4, (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021): 40.

35 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 1A-6.

36 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 1A-4 - 1A-6.

37 Department of Defence, ADF-I-3 – Targeting, 23-25.

38 Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process, 1-6.

39 Defined as “Intelligence products…and activities that incorporate all sources of information, including…human intelligence, signals intelligence, geospatial intelligence and open-source data, in the production of intelligence.” (Department of Defence, ADF-P-2 – Intelligence Ed. 4, (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021): 55.)

40 Department of Defence, ADF-I-3 – Targeting, 28-29.

41 Department of Defence, ADF-I-3 – Targeting, 33.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.