Prologue

This essay was written on 23 September 2022, before the Ukrainian recapture of Kherson in the South in October 2022. It offers a snapshot of the events leading up to that point. An analysis of Russian campaign planning and operations demonstrates how the Clausewitzian trinity of chance, passion and reason continues to hold true and has undermined Vladimir Putin’s military foray into Ukraine.

Introduction

When Russia sent troops across the Ukrainian border in late February 2022 in their “special military operation” few observers thought that the Ukrainian government would last a week given that Russia had a much larger and more powerful military. But eight months later the war continues with more than 13 million Ukrainians displaced, tens of thousands of military and civilian casualties taken on both sides and the disruption of the global distribution of food and fuel. Ukrainian forces, stiffened by significant western military aid, have offered determined resistance. Russia's strategic miscalculations have been aggravated by internal operational problems. Early Russian operational successes and subsequent major reversals demand explanation. This essay will evaluate Russia’s military campaign in the three main phases of the conflict to date: first, the initial offensive to conquer Kyiv; second, the slower, grinding ground war fought from within occupied regions; and, third, the Ukrainian counter-offensive supported by a strong information operations deception campaign.

Central to effective campaign planning is an effective understanding of the arrangement of military operations. This essay will argue that the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine suffered from a poor understanding of the arrangement of military operations leading to inadequate campaign planning and a failure to achieve its political objectives. This essay will highlight the importance of operational art in effective campaign planning and define the three most relevant elements of the arrangement of military operations: main and supporting efforts, sequencing and operational reach. It will then illustrate that in the Russian forces initial push to Kyiv their sequencing and operational reach elements were so poorly planned and insufficient that a relatively small force was able to fight to great effect asymmetrically and bring the advance to a screeching halt. Subsequently, in phase two Russia failed to align its main and supporting efforts with a sound strategic objective. While the Russians demonstrated some capacity for learning and adaptation by better sequencing their operations and extending their operational reach in phase two, this essay demonstrates that Russia’s response to the Ukrainian counteroffensive reveals its persistent resourcing issues as evidenced by more poor sequencing (specifically in the areas of simultaneity and depth). These problems resulted in broad Russian mobilisation and highlight Russia’s overall failure in campaign planning. Russian performance thus far illustrates the importance of a strong understanding of the arrangement of operations in the planning and execution of military campaigns.

Operational art and the arrangement of military operations

Operational art is defined as “the skilful employment of military forces to attain military goals through the design, organisation, sequencing and direction of military actions.”[1] Critically it requires planners to link available resources (means) and military actions (ways) to attain an end state (ends) while considering possible costs (risk).[2] A key component of operational art is the arrangement of military actions, and the way that planners use the arrangements of military action will vary depending upon the complexity of the problem and a range of planning considerations. This was illustrated in the success of the ‘D-day’ Allied landings of World War 2,[3] where suitable resources were built up prior to landings, operations and actions were sequenced across domains, and main and supporting efforts were carefully orchestrated based on known intelligence to achieve best effect.

ADF doctrine highlights eight elements in the arrangement of military operations for campaign planning. In evaluating the effectiveness of the Russian campaign, the most relevant three elements are main and supporting efforts, sequencing and operational reach. Each phase of military action should have an identified main effort: that is, the concentration of forces or means in time and space to bring about a decision.[4] Identifying where and when a main effort ought to be made is critical as it provides focus and achieves a military objective or overall end state. Of equal importance is a force’s supporting efforts, which are the complementary military actions that support the main effort. Identifying supporting efforts similarly allows resources to be prioritised across a campaign. Sequencing refers to the ordering of decisive points into lines of operation and the subsequent ordering of lines of operation into a logical progression in time, space and purpose.[5] Synchronisation, simultaneity and depth, tempo and operational pauses must be considered when sequencing actions. An effective understanding of a force’s operational reach is also central to the successful execution of military operations. Operational reach refers to the distance and duration across which a force element can successfully employ its military capabilities.[6] Together these three key elements in the arrangement of military operations offer a useful lens through which to analyse Russian campaigning in Ukraine.

Phase One: the rapid advance to Kyiv

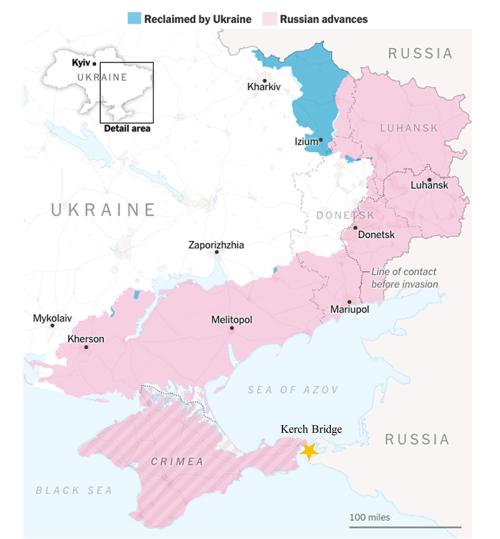

Russia’s failure to capture Kyiv reflected a broader failure of operational planning. Rather than building up an overpowering, synchronised force to achieve their major strategic objective, Russia instead applied military force in ‘battalion-sized penny packets’[7] and neglected both the sequencing of multi-domain efforts and consideration of operational reach. Russia’s offensive soon disintegrated into poorly coordinated efforts by disparate forces suffering from poor command and control. Capitalising on this loss of Russian momentum, Ukraine resisted in both the field and in the information domain. Images of Ukrainian farmers towing Russian AFVs with tractors on social media telegraphed the faltering Russian campaign.[8] Supporting Russian efforts on other fronts—attempting to isolate Ukraine by linking mainland Russia and Crimea[9], employing air and missile attacks against ‘strategic’ targets, and the airborne assault on Kyiv[10] seeking to ‘decapitate’ Ukraine’s leadership—proved fruitless and similarly reflected a lack of joint operational integration and command and control coordination.

Source: The New York Times

Russia’s lack of operational planning resulted in a clear overestimation of its operational reach. Their logistics coordination and resupply planning were centred on the assumption that they would occupy Kyiv within 48 to 72 hours.[11] Instead tanks ran out of fuel and soldiers ran out of food and supplies. Nine weeks of uncoordinated urban warfare obliged the Russians to pull out of Kyiv to reassess and recalibrate their main effort. This failure could have been averted through effective operational planning. While the strength of Ukrainian resistance may have been difficult to predict, supply needs, critical vulnerabilities and risks for convoys should have been understood with sequencing and tempo structured accordingly. Possibly the fall of Baghdad in 2003 to US-led forces may have given Russia false certainty regarding the ease at which a capital city could be taken.[12] Conversely, the difficulties of the US-led forces to clear and secure the city of Fallujah in 2004 demonstrates the power that a small force can wield against a larger opponent in the absence of sufficient joint operational planning when conditions on the battlefield are not adequately shaped, information operations are not considered, and a sufficient force structure is ignored.[13] Reflecting on such historical examples may have proven prudent for Russian operational planning in Ukraine.

In the sequencing for the run to Kyiv, critical joint effects in particular air power were missing from the Russian campaign. The armoured convoys were effectively engaged by low-cost drones.[14] A lack of Russian battlefield awareness on Ukrainian troop movements—evidenced by minimal Ukrainian losses—suggests poor Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR). Russia’s failure to adequately suppress enemy air defence and achieve air superiority, maintain offensive counter air and thus set the necessary conditions to provide ISR and close air support for the armoured convoys, suggests a lack of a coordinated and sequenced Russian plan inclusive of air power. Subsequently, long range cruise missile strikes lacked focus and offered limited strategic benefits. Furthermore, actions in the supporting effort in the southern Kherson oblast were not strong enough to divert Ukrainian resources (including western military aid) away from challenging the Russian main effort in the northern front. The rapid disintegration of the Russian offensive against the relatively small force defending Kyiv shows the importance of linking objectives with available resources in planning.

The ability to execute effective joint operations comes when planning is supported by expertise from all domains. This allows for a proper understanding of strengths and weaknesses to ensure the objectives are realistic, the sequencing of the campaign is achievable and the synchronisation of resources coordinated. Russian endeavours to set the operational tempo across main and supporting efforts appear not to have accounted for the effectiveness of Ukrainian resistance. Therefore the Russian plan lacked the necessary decision points or operational pauses to consolidate and reassess. Unable to take Kyiv, the Russians were forced to change their approach to one that addressed many of their shortfalls. They commenced a slower, grinding approach in service of a new strategic aim: the further occupation of the Donbas region.

Phase Two: grinding barrages in the east

Following the ignominious retreat from Kyiv, the Russian forces needed to reconsider their plan. They began utilising tactics that had become commonplace during their action in Syria.[15] Operating from the Donbas region, Russian forces reverted to an artillery-focused campaign seemingly designed to destroy the will and reap maximum destruction on civilian infrastructure. While the military value of many targets appeared difficult to justify, the information campaigns running at full speed from both sides make the full assessment of Russian intentions of the strikes difficult to determine at this point.[16] This sustained operation marked a shift in Russian tactics, but the strategic intent of this shift remains unclear.

During this period the main effort remained the attacks in the east, with supporting operations in the south. The southern campaign would have greater influence on Russia’s longer-term success and international standing. The operational purpose of the southern campaign was to establish a continuous land bridge between Russia and the Crimean Peninsula.[17] Continuing this to the west would then deny the Black Sea to Ukraine, strangling its ability to export (primarily grain and wheat),[18] which, in turn, would further damage Ukraine’s economy and deplete world food stocks. Operations in the east focused on destruction of civilian infrastructure, keeping Ukrainian forces busy countering the artillery and crushing the Ukrainian people’s will. By not focusing on the strategically significant southern campaign, the Russian attack against Mariupol[19] became a protracted siege, extending the timeline of this supporting effort. The importance of resourcing and application of operational art was clearly lost on the Russian forces whose efforts to terrorise civilians appeared motivated by a desire for vengeance rather than rational military appreciation.

Source: The New York Times

But sequencing through the second phase illustrated the Russians were coming to grips with their military situation. While the order of actions was still not well coordinated, particularly across multi-domain strike, the simultaneity and depth seemed more considered. The volume and range of artillery barrage in the east were proving difficult for Ukraine to counter,[20] and the effectiveness of Ukraine’s low-cost, asymmetric capabilities —so successful in first phase—seemed to wane. With strategic aims more carefully tied to available resources, Russian forces suffered from fewer logistical issues than in phase one.

As the belligerents of World War 1 learned, an industrialised war with high demand on artillery soon stretches ordinance supply.[21] For Russia in 2022, the supply of ordinance to the artillery batteries remains problematic. But the impact of such constraints on Russia’s operational reach has been reduced by containing artillery-focused tactics to the eastern front. In doing so, Russia has successfully reduced the distance for resupply, allowing for simpler and more robust overland logistics—a far cry from the overreach that generated spectacular failure in phase one. At the same time, the delivery of western weapons systems to Ukraine, primarily HIMARS[22], to counter the artillery at longer range has had a tangible impact on the momentum and tempo of this main effort.

Phase Three: Ukraine counteroffensive

Phases one and two demonstrated that the allocation of limited resources between a main and supporting effort must be coordinated as part of the broader operational planning. Following the fall of Mariupol in the south, the objective of controlling Ukrainian port access and maintaining a land bridge had been achieved. Russia strengthened its forces in the south in response to an anticipated Ukrainian counteroffensive.[23] Indications of a Ukrainian strike to the south was designed to cover a counteroffensive in the east, which was launched in September 2022[24] and quickly recaptured territory, meeting relatively light resistance from demoralised Russian troops. Russia's vulnerability to the Ukrainian deception operation emphasises the importance of adequate ISR in enabling planners to balance resources between main and supporting efforts.

The Ukrainian counteroffensive created operational problems for Russia regarding simultaneity and depth. Russia needed to reinforce the eastern front while not drawing too heavily from its forces in the south—the clearest strategic territory. This required the public call for mobilisation, conscripting an initial 30,0000 untrained personnel into military service. Russia’s ability to conduct simultaneous operations was tested and its failure shows the importance in operational planning of setting objectives, tempo and goals that are within one's capabilities and resources. By synchronising efforts more deliberately, particularly across domains, the effects of available capabilities and resources can be maximised. Following a likely Ukrainian strike activity on a key bridge in the Crimean region of the south,[25] Russia has targeted civilians in Kyiv with air and missile strikes. Bombarding civilians has rarely constituted a path to victory.[26]

Source: The New York Times

Operational reach must be clearly understood when planning military campaigns. Of equal importance is understanding enemy operational reach and subsequently selecting targets to reduce it. In the third phase, the resupply of Russian forces in the south was assured by the land bridge of the occupied territories but also enabled by road access through the Crimean Peninsula. The impact on Russian operational reach from the attack on the Kerch Bridge is likely significant. Protecting one’s main supply routes must be a key campaign planning consideration at all levels. Without secure supply, operational reach is critically compromised and goals must be reassessed.

Conclusion

Effective campaign planning requires a strong understanding of operational art to ensure mission success. By understanding operational art, a planner can effectively translate the strategic intent into operational and tactical actions through sound campaign design. Underpinning this is the arrangement of military operations, which assists planners in ensuring that military activities are suitably ordered to enable efficient progress towards achieving the end state by determining the tempo of activities in time, space and purpose.[27] Failure to consider the arrangement of military operations can result in a failure to achieve the strategic objective as demonstrated by Russia’s military efforts in Ukraine in 2022. Learning from the mistakes of others is far cheaper than risking one’s own blood and treasure to relearn them yourself. Therefore, it remains pertinent for military planners to reflect on the valuable lessons learnt from previous conflicts to strategically plan for contemporary military operations.

Epilogue

As argued by Clausewitz, an effective understanding of war needs to account for three key elements: passion (people), chance (military) and reason (government).[28] This analysis of Russia’s campaign planning highlights its failure to adequately consider these elements, undermining Vladimir Putin’s military foray into Ukraine. Russia underestimated the passion of the Ukrainian population, as evidenced by Ukraine’s effective resistance to date, notably as a much smaller and asymmetric force. Russia failed to consider the element of chance, as illustrated by the effective asymmetric impact of Ukrainian tactics against Russian forces and the strong Western support for Ukraine regarding Russian economic sanctions. Likewise, Putin’s government seems disinclined to rationally bind the Russia’s war effort to clear political aim. It is worth considering if this lack of reason is due to Russia’s autocratic system of government as opposed to the balanced debate inherent within a democracy like Ukraine. It is clear that chance, passion and reason remain relevant considerations in modern conflicts. Military planners must consider these elements and ensure they do not underestimate the powerful role the population, the government and the military can play. As the Indo-Pacific will probably become more contested and dangerous in future, Australia must reflect on lessons learnt from the 2022 Russia-Ukraine war and, similar to Ukraine, seek to identify ways to gain an asymmetric advantage over the adversary as a smaller but still capable force.

Disclaimer

This essay was written for the War College. Minor corrections for spelling, punctuation and grammar have been applied to enhance the readability of the essay, however, it is presented fundamentally unchanged from how it was submitted in 2022.

Why is the Kerch Bridge important?, Deutsche Welle, https://www.dw.com/en/why-is-the-kerch-bridge-important-for-russia-and-ukraine/a-63379613.

Ambrose, Stephen E. D-Day: June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War Ii. Simon and Schuster, 2013.

Australian Defence Force. Planning: 5 Series. 1 ed. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021.

Bērziņš, Jānis. "The Theory and Practice of New Generation Warfare: The Case of Ukraine and Syria." The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 33, no. 3 (2020): 355-80.

Boot, Max. "The New American Way of War." Foreign Affairs (2003): 41-58.

Clausewitz, Carl von, Michael Howard, and Peter Paret. On War. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1976.

Dibb, Paul. "China Will Be Watching and Learning from Russia’s Poor Performance in Ukraine." (3 May 2022). https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/china-will-be-watching-and-learning-from-russias-poor-performance-in-ukraine/.

Freedman, Lawrence. "Why War Fails: Russia's Invasion of Ukraine and the Limits of Military Power." Foreign Aff. 101 (2022): 10.

Hubertus Day, Clara Frezal & Marcel Adenauer "The Impacts and Policy Implications of Russia’s Aggression against Ukraine on Agricultural Markets." (5 Aug 2022). https://www.oecd.org/ukraine-hub/policy-responses/the-impacts-and-policy-implications-of-russia-s-aggression-against-ukraine-on-agricultural-markets-0030a4cd/.

Isobel Koshiw, Lorenzo Tondo & Artem Mazhulin. "Ukraine’s Southern Offensive ‘Was Designed to Trick Russia’." (10 Sep 2022). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/sep/10/ukraines-publicised-southern-offensive-was-disinformation-campaign.

Karmanau, Yuras. "Ukraine’s Port of Mariupol Holding out against All Odds." (16 April 2022). https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-kyiv-business-europe-moscow-f5b814ca711f0679cf362016cd46cd47.

Knott, Eleanor. "Existential Nationalism: Russia's War against Ukraine." Nations and Nationalism (2022).

Kuzio, Taras. "Imperial Nationalism as the Driver Behind Russia's Invasion of Ukraine." Nations and Nationalism (2022).

Lawrence, Tony. "The Early Air War." (2022).

McWilliams, Timothy S, and Nicholas J Schlosser. Us Marines in Battle: Fallujah, November-December 2004. History Division, United States Marine Corps, 2014.

Nations, United. "Russian Attacks on Civilian Targets in Ukraine Could Be a War Crime: Un Rights Office." (11 March 2022). https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/03/1113782.

Pape, Robert A. Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War. Cornell University Press, 1996.

Saluschev, Sergey. "Annexation of Crimea: Causes, Analysis and Global Implications." Global Societies Journal 2 (2014).

Snyder, Timothy, Yulia Kazdobina, Olexander Scherba, Luke Cooper, and Mary Kaldor. "Is a Peace Deal Possible with Putin? On the Problems of Peacemaking in the Russian War on Ukraine." (2022).

Strachan, Hew. "Shells Crisis of 1915." International Encyclopaedia of the First World War (2016).

Torulagha, Priye S. "The Russo-Ukrainian War: It Is Time for a Negotiated Settlement to Avoid Military Quagmire and a Possible 3rd World War."

"Ukrainian Counter-Offensive in North-East Inflicts a Defeat on Moscow." (10 Sep 2022). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/sep/10/ukrainian-forces-kupiansk-advances-north-east-russia-izyum.

1 Australian Defence Force, Planning: 5 Series, 1 ed. (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021), 14.

2 Australian Defence Force, Planning: 5 Series, 3.

3 Stephen E Ambrose, D-Day: June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II (Simon and Schuster, 2013).

4 Australian Defence Force, Planning: 5 Series, 62.

5 Australian Defence Force, Planning: 5 Series, 16.

6 Australian Defence Force, Planning: 5 Series, 15.

7 Paul Dibb, "China will be watching and learning from Russia’s poor performance in Ukraine," (3 May 2022). https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/china-will-be-watching-and-learning-from-russias-poor-performance-in-ukraine/.

8 Eleanor Knott, "Existential nationalism: Russia's war against Ukraine," Nations and Nationalism (2022).

9 Taras Kuzio, "Imperial nationalism as the driver behind Russia's invasion of Ukraine," Nations and Nationalism (2022).

10 Tony Lawrence, "The Early Air War," (2022): 2.

11 Dibb, China will be watching

12 Max Boot, "The new American way of war," Foreign Affairs (2003): 44.

13 Timothy S McWilliams and Nicholas J Schlosser, US Marines in Battle: Fallujah, November-December 2004 (History Division, United States Marine Corps, 2014), 67.

14 Lawrence Freedman, "Why War Fails: Russia's Invasion of Ukraine and the Limits of Military Power," Foreign Aff. 101 (2022): 20.

15 Jānis Bērziņš, "The theory and practice of new generation warfare: The case of Ukraine and Syria," The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 33, no. 3 (2020).

16 United Nations, "Russian attacks on civilian targets in Ukraine could be a war crime: UN rights office," (11 March 2022). https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/03/1113782.

17 Sergey Saluschev, "Annexation of Crimea: Causes, analysis and global implications," Global Societies Journal 2 (2014).

18 Clara Frezal & Marcel Adenauer Hubertus Day, "The impacts and policy implications of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine on agricultural markets," (5 Aug 2022). https://www.oecd.org/ukraine-hub/policy-responses/the-impacts-and-policy-implications-of-russia-s-aggression-against-ukraine-on-agricultural-markets-0030a4cd/.

19 Yuras Karmanau, "Ukraine’s port of Mariupol holding out against all odds," (16 April 2022).https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-kyiv-business-europe-moscow-f5b814ca711f0679cf362016cd46cd47.

20 Priye S Torulagha, "The Russo-Ukrainian War: It is Time for a Negotiated Settlement to Avoid Military Quagmire and a Possible 3rd World War."

21 Hew Strachan, "Shells Crisis of 1915," International Encyclopaedia of the First World War (2016): 1.

22 Timothy Snyder et al., "Is a peace deal possible with Putin? On the problems of peacemaking in the Russian war on Ukraine," (2022): 10.

23 Lorenzo Tondo & Artem Mazhulin Isobel Koshiw, "Ukraine’s southern offensive ‘was designed to trick Russia’," (10 Sep 2022). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/sep/10/ukraines-publicised-southern-offensive-was-disinformation-campaign.

24 "Ukrainian counter-offensive in north-east inflicts a defeat on Moscow," (10 Sep 2022). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/sep/10/ukrainian-forces-kupiansk-advances-north-east-russia-izyum.

25 Why is the Kerch Bridge important?, Deutsche Welle, https://www.dw.com/en/why-is-the-kerch-bridge-important-for-russia-and-ukraine/a-63379613.

26 Robert A Pape, Bombing to win: Air power and coercion in war (Cornell University Press, 1996).

27 Australian Defence Force, Planning: 5 Series, 14.

28 Carl von Clausewitz, Michael Howard, and Peter Paret, On war (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1976), 89.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.