Introduction

The Australian military’s relatively small size and breadth of operations have always meant that innovation was necessary to apply military violence against an adversary and succeed. The 2020 Defence Strategic Update warns that the Australian Defence Force (ADF) is increasingly faced with a more complex environment as Australia’s potential adversaries and threats are progressively affecting multiple domains simultaneously.[1] The threat sources are becoming broader and hybridised as they emerge from traditional state actors, international non-state groups, and environmental causes.[2] The degradation of the strategic environment requires the ADF increasingly respond through coordinated actions in each domain of air, land, maritime, space and cyber. The ADF must methodically consider force design and operational capability in an ever-increasingly complex strategic environment.

Since the former Defence Secretary, Paul Dibb, successfully argued for a more integrated ADF, capable of joint operations, the conjecture has remained as to the appropriate level of integration.[3] Historically, the Australian military had conducted command, operations, procurement and targeting in a service-specific manner. The introduction of joint operations allowed the new ADF to abolish service level restrictions and adapt to new emerging concepts such as the US’s air-land battle of the late 20th century.[4] For the ADF to maintain relative superiority over potential adversaries, it must consider how to best integrate the effects of each of its domains.

This essay argues that the ADF should primarily consider joint multi-domain systems to create adaptive ‘kill webs’ to succeed in the contemporary environment. This paper evaluates the historical ‘service, platform, and network-driven’ models to discern limitations in the ADF’s ability to generate critical joint systems of Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) to defend and Joint Fires and Effects (JFE) to attack potential adversaries. Using the two examples of IAMD and JFE, this paper analyses the ADF’s capacity against future threats using an evaluation criterion of current need, current state, and desired future state. Firstly, identifying the need for ‘kill webs’ within the contemporary environment. Secondly, the current ADF is evaluated for its use of historical models to create resource efficiency for developing the force to meet contemporary needs. Finally, the complexity of the strategic environment necessitates the evaluation of the adaptation of the system.

Defining the need for ‘kill webs’

The ADF’s ability to apply military effects against current and emerging threats relies on the evaluation of the system to meet the needs of the contemporary environment. In the JFE and IAMD system, the most appropriate is one that can adapt to the threat’s actions and achieve the desired outcome. Therefore, this section will define the historical means to detect threats and deliver effects through service and platform-based ‘kill chains’. Subsequently, this section will define the assessed potential adversary's capability to disrupt the ‘kill chain’. Finally, this section will define and describe ‘kill webs’ as an effective means to combat future threats.

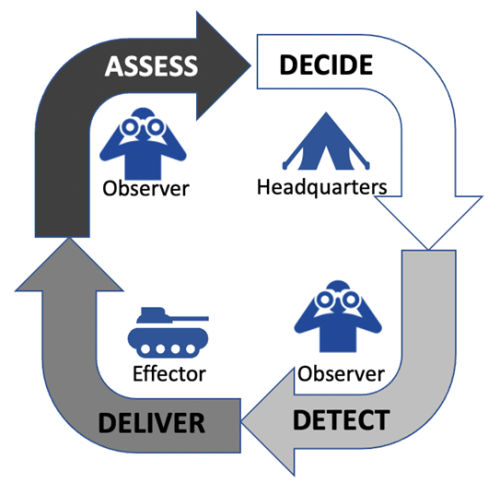

The historical model of ADF system thinking can be described as the ‘kill chain’ model. This type of system is typically a simple and logical service, platform, and network-driven system that can contend with a specific threat. For instance, the Australian Army historically employs and designs artillery systems in the ‘kill chain’ model, see figure 1. Australian artillery is like most ADF targeting systems, with three integral components that enable a simple ‘kill chain’.[5] Firstly, the headquarters decide which targets need to be affected.[6] The observers are dispatched to detect conventional threats such as enemy tanks and then transmit the information over a communications system to a headquarters.[7] The headquarters then decide on delivering an effect that should be executed.[8] Subsequently, the decision and information are transmitted to a firing unit to deliver the effect. Finally, the observer assesses the effects and provides situational awareness to the rest of the system.[9] This simple system has proven to be historically effective, though the linear nature of the system does have vulnerabilities, such as predictability.

The ‘kill chain's’ limitations are due to the capability of the system’s component parts and the simplicity of the system. For example, the observer only has a limited range of movement and detection, relying primarily on visual detection. Therefore, in a simple ‘kill chain’, the headquarters is limited to a single assessment from one observer method. Furthermore, the headquarters is limited in considering the most appropriate delivery system to employ. Delivery systems, like artillery, can have multiple limitations, such as legal considerations or weapon limitations due to collateral damage concerns because of civilians or friendly troops in the area. In considering the system limitations, it can be deduced that JFE and IAMD targeting conducted through simple ‘kill chains’ limits a commander’s ability to have the desired effect and is vulnerable to an adversary that can exploit the inherent limitations of the detection and delivery components.

The ADF's potential adversaries are becoming increasingly sophisticated in achieving multi-domain effects and avoiding ‘kill chains’. In the last ten years, there have been examples of state and non-state actors that can avoid simple ‘kill chains’ and use other methods to achieve their intentions or deliver their desired effects. For example, the military actions against Islamic State (IS) demonstrated the capacity of adversaries to undermine the simple ‘kill chains’ through a blend of non-state characteristics of dispersion, modularity and autonomy with more conventional fighting force methods.[11] IS fighting forces could remain below the detection threshold through the dispersion of their forces and integration among the civilian population through tactics and procedures such as semi-regular fighting forces and clandestine means such as assassinations, raids and suicide bombing.[12] This tactic defeats visually reliant systems, shown in figure 1, such as observers and unmanned aerial vehicles. The IS forces would then rapidly concentrate on a specific mission, achieve their effect, such as the seizure of terrain and then return to the previous undetectable state.[13] However, the IS relied heavily on communication networks to achieve a rapid concentration.[14] Therefore, for the ADF to create a system that can defeat an adversary such as the IS or state actors, JFE and IAMD systems require the ability to detect early adversary intentions by methods such as space, cyber and the electromagnetic spectrum to inform subsequent visually based detection. Furthermore, to have an increased impact, the ADF's system should seek to simultaneously deliver effects that disrupt the fighting force, the command structure and informational terrain by both lethal and non-lethal methods.

Increasingly state actors such as China and Russia are displaying capabilities and willingness to employ multi-domain integration to undermine western fighting systems. As adversary nations attempt to avoid catastrophic losses, there is a propensity to increase capabilities in the whole of government functions and various military means.[15] This means that China and Russia also seek to disrupt traditional functions by establishing stand-off capabilities such as anti-access and area denial systems, irregular means such as paramilitary forces and multi-domain effects including cyber and space.[16] Chinese overt and subversive military actions in the South China Sea and elsewhere in the Indo-Pacific region prove Australia's need to reconsider its current threats.[17] Therefore the future ADF should consider how it detects and counters future state and non-state threats across all domains.

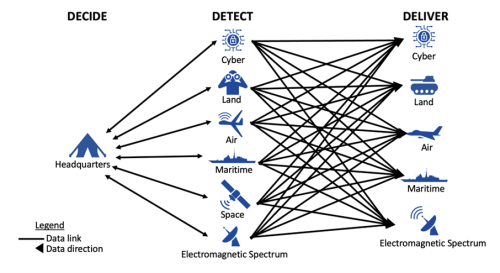

The ‘kill web’ is a solution to the contemporary dilemma of defeating adversaries seeking to undermine historical ‘kill chains’. The term ‘kill web’ is an amalgamation of different domains’ ‘kill chains’ into one system, exponentially increasing the force’s ability to achieve JFE and IAMD.[18] The ‘kill web’ system shown in figure 2 illustrates how a commander has increased detection and delivery options to maintain military superiority over an adversary regardless of their tactics or capabilities. Consequently, the term ‘kill web’ becomes an apt metaphor for a spider’s web; as a target interacts with a strand, the neighbouring strands confirm the interaction, and the target cannot escape the web's ability to respond with effects. However, US Army officer Dennis Wille argues that for a force to create a multi-domain ‘kill web’, consideration must be made to establish guiding principles. Wille offers that a force must conceptually consider its force disposition and posture in an area of operation, the creation of multi-domain formation, and the convergence of layered and cross-domain synergised effects.[19] Therefore, for the ADF to create ‘kill webs', the force depends on function detection, command and delivery nodes, and appropriate procedures and culture to create an adaptive force enabled by mission command to achieve decision superiority over the adversary.

Evaluation of the ADF’s current capacity

In considering the most effective model for force generation of IAMD and JFE, Australia’s requirements should always premise efficient use of its limited resources. As Australia’s domain ability to affect a domain is threatened, there is a natural corresponding response by the ADF as workforces are increased into vulnerable sectors such as cyber and space. Therefore, threats will be increasingly demanding on Australia’s limited resources. This section evaluates the historical ADF service-based model to achieve ‘kill webs’ against Australia’s ability to efficiently use its most finite resources of finance, people, and time.

The ‘service, platform and network’ model does have efficiency in its procurement cycle and consistency in force design. The inherent efficiency is created by military services like the Navy and Army procuring platforms such as ships and vehicles and force designing units based on discrete modernisations to the existing equipment and structures. This paradigm allows for efficient time and force management as the services do not require expensive modifications, slow change management cycles or justification to other services and government. An example is the Royal Australian Navy’s surface combatant fleet which has consisted of similar numbers in the fleet since the end of the Second World War with little rationale or justification.[21] The purpose of the surface combatant fleet is necessary for traditional naval roles such as securing maritime borders, policing illegal activities, and supporting search and rescue. Therefore, replacing the ageing Adelaide Class of ships with Hobart Class destroyers becomes an obvious Navy decision, efficient for the service and ADF.[22] However, the ADF increasingly needs efficiency in its people and money by having elements such as naval vessels to support joint operations and produce joint effects.[23] The 2016 white paper notes that the surface combat fleet has increased pressure to act as a sensor and effector for the joint force.[24] Thus more efficiency can be achieved with the networking and decision-making of traditional systems to support the joint force.

The efficiency of the traditional ‘service, platform and network’ system has the potential to create a situational Service-based bias that produces long-term inefficiency. The ADF’s continued iterative modernisation system allows services to create short-term efficiency based on known domain requirements through simple ‘kill chains’. However, insufficient scrutiny of the collective joint force requirements creates increasingly long-term force structure and procurement inefficiencies as systems require modification after procurement. As an extension of the Hobart Class destroyer example, the asset has proven that it is a highly capable system in its primary role as a fleet combat asset. The modernisation outcomes in the maritime domain are due to new and novel systems, such as the Aegis combat system, that provides a level of automation that enables next-generation linked command, combat, and detection systems more effectively than the Australian Navy has ever employed.[25] The Hobart class is a surface combat vessel with the potential to be a highly effective joint force enabler in both the IAMD and JFE.[26] The Aegis system links the Hobart and future Hunter Class fleet and F35 Joint Strike Fighter, yet legacy joint platforms have to rely on legacy voice and data communications. However, the ADF has yet to bring enabling systems such as the future AIR 6500 Battle Management System, the potential of Aegis is reduced to a discrete yet optimised maritime effect.[27] Therefore, while an opportunity in one service might enhance its domain dominance if the ADF does not consider the joint integration the potential joint force will continue to lack the capacity to achieve ‘kill webs’. If the generational shifts are only created in small elements of the ADF they will be unsuitable for the potential future threats that require sophisticated networking to dominate all domains.

The ADF must create efficiency for the joint force to dominate the multi-domain battle space effectively. The efficiency created by establishing functional 'kill webs’ must consider the enabling elements of communications, command structure and enabling fighting platforms as the driving consideration for the ADF to create functional JFE and IAMD systems. The future procurement of AIR 6500 is a necessary element of IAMD and JFE for detection, decision-making, and delivering the attack with the most appropriate weapon system across the domains.[28] This form of IAMD has yet to be proven by the ADF, though enabled with joint integrated command and control systems, it is possible with the services procuring the support systems in the form of the Army's new ground-based air defence system, Air Force's F35s and Navy's Destroyers. The ADF can avoid shortfalls of the Hobart Class optimisation by future joint design thinking to establish a new procurement and fighting method separate from historical and ineffective ‘service, platform and network’ systems.

Evaluation of the ADF’s future opportunities and limitations

For the ADF to build a capable multi-domain force proficient in generating JFE and IAMD ‘kill webs’, the ADF must consider long-term implications to exploit opportunities and avoid limitations. While optimising the current system is integral to creating a force against the evolving threat, studying future trends allows for better methods to achieve enduring superiority. Therefore, this section considers how the ADF can enhance future systems through cultural and technological initiatives.

Creating a culture for multi-domain integration is a socio-technical enterprise due to the complex relationship of people, service structures, enabling technology and existing processes. JFE and IAMD ‘kill webs’ reframes how the ADF employs and structures the force to achieve the full effect in the future. One possible option is the British Ministry of Defence's proposal for an optimal method to enable the future force through education and a revision of existing force components.[29] This proposal does not abolish service expertise, as domain excellence is still required. Instead, the integration requires the standardisation of the forces’ command processes, a drive for delegation of authorities to achieve mission command, and adaptive operational teaming.[30] This proposal could see traditional military hierarchical structures flattened in preference for agile functional commands such as joint IAMD commands. The cost of the British proposal is that it is likely an expensive undertaking in time and money, with substantial risk if the ADF were to adopt an experimental force structure. However, to gain a military advantage over potential adversaries, the ADF must empower leaders to create change and innovation within the force. Through this method, the ADF creates a command, teaming and learning culture that is adaptive to the environment.

Education is critical for developing rapid non-linear solutions to create adaptive and effective multi-domain ‘kill webs’. The ADF must maximise human potential through the way that it instructs and trains its individuals. The US Army defines this need as a critical force implication to foster trust in the force necessary to operate in a chaotic and ambiguous environment as an adversary undermines existing ‘kill chains’ or adapts to ‘kill webs’.[31] The ADF must familiarise individuals with multi-domain capabilities while equipping them with intellectual resilience to operate in complex situations. Continuous review of instructional institutions, exercising, and feedback processes will better integrate cross-domain thinking and design.

The future of the multi-domain ‘kill web’ will be the continuing enhancement of links and nodes. A mathematics study shows that adaptive ‘kill webs’ are possible and can be optimised through complex design methods of nodal linkages. The system shown in figure 2 demonstrates the complexity of the multi-domain ‘kill web’ due to the amount of data necessary for the web to be successful.[32] However, the limitation of the experiment was it assumed the capacity of personnel in the command nodes to receive the volume of information, process the data and understand the information to make rational decisions.[33] The recommendation was to consider artificial intelligence to create faster and more dependably rational decisions.[34] While the proposed integration of artificial intelligence into command and control systems could optimise ADF ‘kill webs’, there are weaknesses within the current system that would need to be adapted.[35] The ADF must become increasingly familiar and confident with enabling emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and advanced computing. This would allow the force to continue to grow with the possibilities of its personnel and systems.

Conclusion

This essay has argued that adaptive and technologically enabled threat actors have degraded the strategic environment; the ADF must consider how it creates multi-domain forces that can build ‘kill webs’ to combat its adversaries effectively. By evaluating the strategic operating environment, the paper has shown that the adversary easily undermines the traditional service and capability-based ‘kill chains’. The ‘kill web’ methodology increases the potential of each service and capability-based ‘kill chain’ to have a more significant cumulative effect on the mission. The ADF will always need to balance its flexibility to combat state and non-state threats against using limited resources. Therefore, the ADF will need to inform services to ensure the joint system takes primacy to use its time, people and money most efficiently.

The ADF must consider the future force it aims to achieve and set the conditions through leadership and educational development. The historical methods for force design, integration and capability procurement were efficient for their original purpose yet were shown to have limitations in the future operating environment. By creating a culture and structure for change and critical thought, the ADF can maximise its workforce for multi-domain integration. This change requires a concerted effort from the ADF to achieve talent management and empower its leaders to embrace the intellectual challenge of creating functional multi-domain systems. The failure to do so will likely cause individuals and organisations to fall back into traditional service, capability and system models that create efficient ‘kill chains’ but will degrade the overall force opportunities.

The multi-domain ‘kill web’ is not an answer in itself but a frame of thinking the ADF can use in the future. The ADF can ensure that its forces are not solely reliant on technological advancements to defeat an adversary but produces a resilient force that harnesses the talent of its people. Continual refinement through learning, adaptation, exercising and technology adoption will aid in achieving the overall potential of the system.

Disclaimer

This essay was written for the War College. Minor corrections for spelling, punctuation and grammar have been applied to enhance the readability of the essay, however, it is presented fundamentally unchanged from how it was submitted in 2022.

Australia, The Parliament of the Commonwealth of. Australian Defence Review. ACT, Australia: Commonwealth Government Printing Office, 1972.

Basan, Thomas. "Time for a New Approach to War? A Case for Adopting the Kill Chain Concept." The Cove (2019).

Centre, Army Knowledge. "Chapter 1: Deployment - an Overview." In Lwp-Ca (Os) 5-3-1 Gun Deployment and Routine, edited by Australian Army, 2018.

Defence, Department of. 2020 Defence Strategic Update. https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2020-defence-strategic-update: Australian Government, 2020.

———. Defence White Paper. Canberra: Australian Government, 2016.

———. "Joint Air Battle Management System." Defence Projects (2022). https://www.defence.gov.au/project/joint-air-battle-management-system.

Dibb, Paul. Review of Defence’s Capabilities. ACT, Australia: Australia Government Publishing Service, 1986.

Directorate, Joint Doctrine. Addp 3.1 Joint Fires and Effects. Operations Series. 4 ed., 2020.

Garn, Alex R. "Multi-Domain Operations: The Army’s Future Operating Concept for Great Power Competition." School of Advanced Military Studies, US Army Command and General Staff College (2019).

Grey, Jeffrey. A Military History of Australia. Third ed. USA: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Hashim, Ahmed S. "The Islamic State’s Way of War in Iraq and Syria: From Its Origins to the Post Caliphate Era." Perspectives on Terrorism 13, no. 1 (2019).

Headquarters, Department of the Army. "Chapter 2: The Targeting Methodology." In Fm 3-60, the Army Targeting Process. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2010.

Isaac Lewellen, James Patrick and Larry Jennings. "From Sensor to Shooter Faster." Army Acquisition, Logistic and Technology (AL&T) Magazine Summer (2019).

Johnston, Patrick Ryan and Patrick B. "After the Battle for Mosul, Get Ready for the Islamic State to Go Underground." War on the Rocks (2016). https://warontherocks.com/2016/10/after-the-battle-for-mosul-get-ready-for-the-islamic-state-to-go-underground/.

Keck, Zachary. "Would You Like an F-35 with Your Aegis?". The Diplomat (2014).

Killcullen, David. The Dragons and the Snakes: How the Rest Learned to Fight the West. Victoria: Scribe Publications, 2020.

Leben, William. Defence Review Needs to Consider Advanced Command-and-Control Capabilities for the Adf. The Strategist. Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2022.

Luyao Wang, Libin Chen, Zhiwei Yang, Minghao Li, Kewei Yang and Mengjun Li. "A Prospect-Theory-Based Operation Loop Decision-Making Method for Kill Web." Mathematics 10 (2022).

Oelrich, Stephen Biddle and Ivan. "Future Warfare in the Western Pacific: Chinese Antiaccess/Area Denial, U.S.Airsea Battle, and Command of the Commons in East Asia." International Security 41, no. 1 (2016).

Office, Australian National Audit. "Project Data Summary Sheet: 2019-20 Major Project Report Sea 4000 Phase 3 Air Warfare Destroyer ". Auditor-General Report No.19 2020–21 (2020).

Palazzo, Albert. "Multi-Domain Battle: Meeting the Cultural Challenge." The Strategy Bridge (2017). https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2017/11/14/multi-domain-battle-meeting-the-cultural-challenge.

Romjue, John. "The Evolution of the Airland Battle Concept." Air University Review May-June (1984).

The Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre. Joint Concept Note 1/20: Multi-Domain Integration. www.gov.uk/mod/dcdc, 2020.

TRADOC, US. Tradoc Pamphlet 525-3-1: The Us Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028, 2018.

Wille, Dennis. "A Summary of Multi-Domain Operations." In The Army and Multi-Domain Operations:: Moving Beyond Airland Battle. Washington DC: New America, 2019.

1 Department of Defence, 2020 Defence Strategic Update, 11-17 (https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2020-defence-strategic-update: Australian Government, 2020).

2 Defence, Short 2020 Defence Strategic Update, 11-17.

3 Paul Dibb, Review of Defence’s Capabilities, 1-4 (ACT, Australia: Australia Government Publishing Service, 1986).

4 John Romjue, "The Evolution of the AirLand Battle Concept," Air University Review May-June (1984): 4-15.

5 Basan describes kill chains as an optimal method for domain systems to execute processes efficiently. The article describes multiple separate domains that can establish kill chains. Thomas Basan, "Time for a New Approach to War? A Case for Adopting the Kill Chain Concept," The Cove (2019).

6 Army Knowledge Centre, "Chapter 1: Deployment - An Overview," in LWP-CA (OS) 5-3-1 Gun Deployment and Routine, ed. Australian Army (2018), Section 1-4.

7 Centre, "Chapter 1: Deployment - An Overview," Section 1-4.

8 Centre, "Chapter 1: Deployment - An Overview," Section 1-4.

9 Centre, "Chapter 1: Deployment - An Overview," Section 1-4.

10 Joint fires and effects doctrine Department of the Army Headquarters, "Chapter 2: The Targeting Methodology," in FM 3-60, the Army Targeting Process (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2010), 2-1 - 2-19.

11 David Killcullen, The Dragons And The Snakes: How The Rest Learned To Fight The West (Victoria: Scribe Publications, 2020), 82-83, 94-95.

12 Ahmed S. Hashim, "The Islamic State’s Way of War in Iraq and Syria: From its Origins to the Post Caliphate Era," Perspectives on Terrorism 13, no. 1 (2019): 22-31.

13 Patrick Ryan and Patrick B. Johnston, "After the Battle for Mosul, Get Ready for the Islamic State to go Underground," War on the Rocks (2016), https://warontherocks.com/2016/10/after-the-battle-for-mosul-get-ready-for-the-islamic-state-to-go-underground/; Hashim, "The Islamic State’s Way of War in Iraq and Syria: From its Origins to the Post Caliphate Era," 22-31.

14 Kilcullen describes this as the principles of hiding in electronic plain sight and the use of technology and connectivity hacking. Killcullen, The Dragons And The Snakes: How The Rest Learned To Fight The West, 82-83.

15 Alex R. Garn, "Multi-Domain Operations: The Army’s Future Operating Concept for Great Power Competition," School of Advanced Military Studies, US Army Command and General Staff College (2019): 18-20.

16 Garn, "Multi-Domain Operations: The Army’s Future Operating Concept for Great Power Competition," 18-20.

17 Stephen Biddle and Ivan Oelrich, "Future Warfare in the Western Pacific: Chinese Antiaccess/Area Denial, U.S.AirSea Battle, and Command of the Commons in East Asia," International Security 41, no. 1 (2016): 7-14.

18 James Patrick and Larry Jennings Isaac Lewellen, "From Sensor to Shooter Faster," Army Acquisition, Logistic and Technology (AL&T) Magazine Summer (2019): 106-10.

19 Dennis Wille, "A Summary of Multi-Domain Operations," in The Army and Multi-Domain Operations:: Moving Beyond AirLand Battle (Washington DC: New America, 2019), 9-12.

20 Joint Doctrine Directorate, ADDP 3.1 Joint Fires and Effects, 4 ed., Operations Series, (2020), Chap 3 3-1 - 3-10.

21 Jeffrey Grey, A Military History of Australia, Third ed. (USA: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 208-09, 30, 65; The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Australian Defence Review, 22 (ACT, Australia: Commonwealth Government Printing Office, 1972); Dibb, Short Review of Defence’s Capabilities, vi, 8.

22 Department of Defence, Defence White Paper, 89-93 (Canberra: Australian Government, 2016).

23 Defence, Short Defence White Paper, 89-93.

24 Defence, Short Defence White Paper, 89-90.

25 Australian National Audit Office, "Project Data Summary Sheet: 2019-20 Major Project Report SEA 4000 Phase 3 Air Warfare Destroyer " Auditor-General Report No.19 2020–21 (2020): 141-50.

26 Office, "Project Data Summary Sheet: 2019-20 Major Project Report SEA 4000 Phase 3 Air Warfare Destroyer ".

27 Zachary Keck, "Would You Like an F-35 With Your Aegis?," The Diplomat (2014).

28 Department of Defence, "Joint Air Battle Management System," Defence Projects (2022), https://www.defence.gov.au/project/joint-air-battle-management-system; William Leben, Defence review needs to consider advanced command-and-control capabilities for the ADF, The Strategist, (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2022).

29 Concepts and Doctrine Centre The Development, Joint Concept Note 1/20: Multi-Domain Integration, 53-70 (www.gov.uk/mod/dcdc 2020).

30 Albert Palazzo, "Multi-Domain Battle: Meeting the Cultural Challenge," The Strategy Bridge (2017),https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2017/11/14/multi-domain-battle-meeting-the-cultural-challenge.

31 US TRADOC, TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1: The US Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028, x, 19 (2018).

32 Libin Chen Luyao Wang, Zhiwei Yang, Minghao Li, Kewei Yang and Mengjun Li, "A Prospect-Theory-Based Operation Loop Decision-Making Method for Kill Web," Mathematics 10 (2022).

33 Luyao Wang, "A Prospect-Theory-Based Operation Loop Decision-Making Method for Kill Web."

34 Luyao Wang, "A Prospect-Theory-Based Operation Loop Decision-Making Method for Kill Web."

35 Leben, Defence review needs to consider advanced command-and-control capabilities for the ADF.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.