Introduction

Clausewitz defines the concept of the centre of gravity (COG) as ‘the hub of all power and movement, on which everything depends. That is the point against which all our energies should be directed’.[1] Military planners across the Western world have recognised the importance of this concept, capturing it in military planning doctrine. Australia is no exception and first incorporated COG as a concept in 1998, and more recently, detailing the criticality of the centre of gravity within the Australian Defence Force Procedure 5.0.1 – Joint Military Appreciation Process (herein referred to as JMAP). Joseph Strange, a professor of strategic studies, and Colonel Richard Iron, British Army, define the centre of gravity as

‘the primary entity that possesses the inherent capability to achieve an objective or the desired end state’, which the JMAP has adopted.[2] Despite the recognised importance of the centre of gravity, the JMAP nests the derivation and analysis of the centres of gravity within the broader process of Mission Analysis.[3] The implication is that the importance of the centre of gravity, as a sub-step, is obscured in favour of conducting the superior processes within the JMAP. The enemy's centre of gravity and that of friendly forces are separated by process[4], adding further planning complexity. In an increasingly complex multi-domain environment, the Australian Defence Force must afford the centre-of-gravity analysis an appropriate level of intellectual rigour in order that the military appreciation process realises tangible objectives.

This essay will briefly describe the centre-of-gravity construct and its placement in the JMAP context. The comparative applications of the centre of gravity of other military planning processes will be considered and used as a basis to improve the ADF’s construct within the JMAP. The essay will then argue that centre-of-gravity analysis and development would benefit significantly from being elevated to a primary step in the JMAP process, cognitively reinforcing its importance in designing a concept of operations. The essay will then argue that the centre-of-gravity construct provided in the JMAP is hierarchical and struggles to grapple with the increasingly complex nature of modern warfare. This essay will consider how the centre-of-gravity process might benefit from a system-of-systems approach empowered through advanced technologies and artificial intelligence (AI), delivering a complex adaptive system. This essay will then argue that embedded critical and design thinking will enhance the analysis and development of the ADF’s centres of gravity and avoid a checklist approach to operational planning. Modern warfare is becoming increasingly complex, and Australian doctrine must provide a centre-of-gravity process that is deeply considered, non-linear and adaptable to emerging conditions. As such, the essay will argue that the JMAP risks driving a linear checklist approach to the centre-of-gravity analysis, delivering a campaign plan that is ‘mechanistic, reductionist and inadequate for an increasingly complex battlespace and array of missions’.[5]

Defining the centre of gravity in a JMAP context

The JMAP’s definition of a centre of gravity relies on Dr Joseph L. Strange and Colonel Richard Iron’s interpretation of Clausewitz’s description of the centre-of-gravity concept. Strange and Iron argue that centres of gravity are not limited to physical characteristics, capabilities, or locations, nor is a centre of gravity a single ‘hub of all power and movement’.[6] Instead, they provide a nuanced approach of ‘dynamic and powerful physical and moral agents of action or influence with certain qualities and capabilities that derive their benefit from a given location or terrain’.[7]

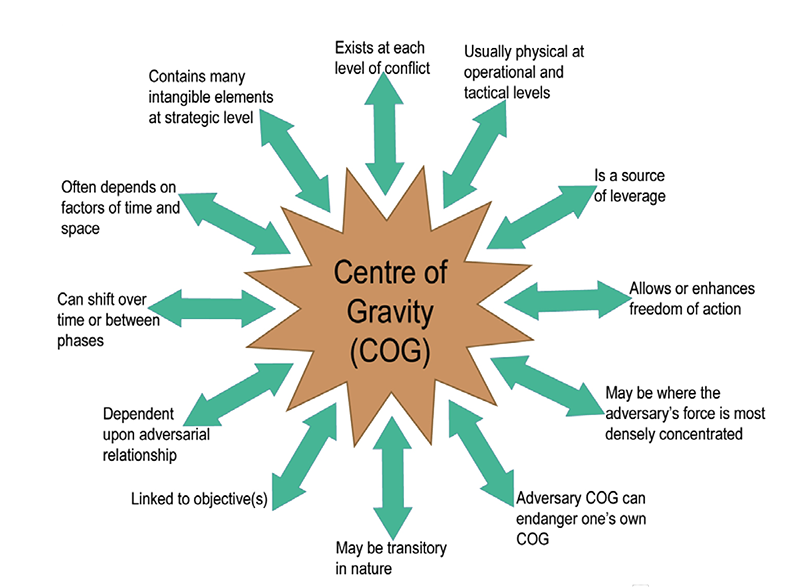

The JMAP offers that Strange and Iron’s centre-of-gravity construct is a helpful analytical tool for planners to ‘identify friendly and adversary sources of strength and vulnerability [and] must continually be studied and refined … due to the dynamic and fluid nature of interactions in the operational environment’.[8] The JMAP provides characteristics likely to be attributed to a centre of gravity, reproduced below in Figure 1. The centre-of-gravity construct is the sum of its constituent parts labelled as critical factors. These critical factors are comprised of critical capabilities (CC), critical requirements (CR), and critical vulnerabilities (CV) and are represented as a hierarchical framework to support analysis.[9] This essay will discuss the details and interrelationship of these critical factors.

Figure 1 – Characteristics of a centre of gravity[10]

The centre of gravity as a planning tool: A brief comparison

Clausewitz’s proposition of the centre of gravity has been interpreted in several ways for Western military operational design and planning. The United States Joint Chiefs of Staff Joint and Coalition Warfighting Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design prioritises the centre of gravity above other concepts in planning in a system-of-systems networked approach, noting, ‘One of the most important tasks … during operational design is the identification of friendly and enemy COGs [centre of gravities] early in planning [to] focus the operational approach’.[11] This essay will argue that the JMAP would most benefit from the approach provided in the Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design.

Enhancing the centre of gravity as a complex adaptive system through a system-of-systems approach, advanced technologies, and artificial intelligence

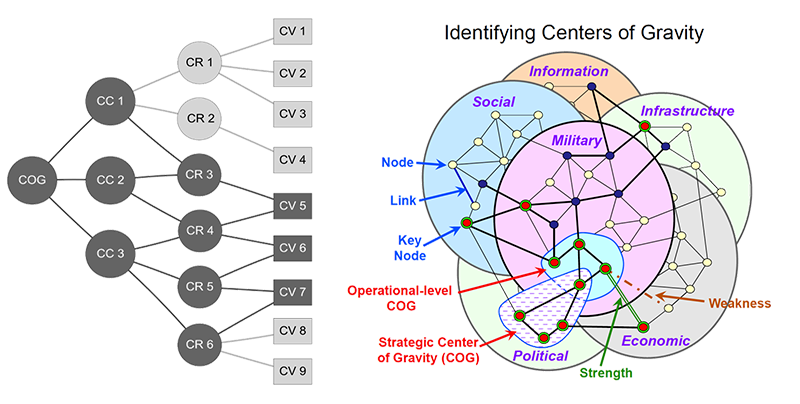

A simplistic representation as a sub-step within the JMAP process obscures the complexity of centres of gravity as an adaptive system. Comparing the ADF’s doctrinal example to that of the US Joint Staff and Coalition Warfighting Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design, provided in Figure 2, reveals a simplistic model of visually representing the breakdown of the critical capabilities (CC), critical requirements (CR) and critical vulnerabilities (CV). The JMAP model represents a linear logic path from the vulnerability to a given centre of gravity. Whilst the JMAP representation provides some appreciation that a critical requirement has multiple critical vulnerabilities, it cannot adequately depict where those critical vulnerabilities might exist for multiple centres of gravity.

JMAP U.S. Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design

Figure 2 – Centre of gravity identification comparison[12]

Additionally, as a manual mapping process, the construct relies entirely on a planner having the time and foresight to estimate how changes in a dynamic environment may have impacted critical factors. The JMAP notes conducting a review cycle as required; however, this is targeted at the primary step of Mission Analysis and its nine sub-steps. Elevating the centre-of-gravity assessment to a primary step would attract commensurate investment of time and, by extension, advanced approaches in modelling.

The JMAP’s current approach to modelling the relationship of critical factors risks a myopic view of any given centre of gravity. It overlooks the interconnectedness of critical factors amongst multiple centres. As ADF planners execute the JMAP, there is potential that a common thread between critical vulnerabilities within divergent centres of gravity is not identified.[13] This essay has demonstrated how Strange and Iron’s definition of the centre of gravity in the JMAP is hierarchically structured in a tree format that captures direct relationships.[14] The implication is that the JMAP cannot capture the indirect relationships between multiple centres of gravity. The JMAP would be significantly enhanced by adapting the centre-of-gravity construct to a system-of-systems network approach to better adapt to environmental complexity. Major Robert Umstead and Lieutenant Colonel David R Denhard have proposed a method to achieve a networked view of centres of gravity through the prism of effects-based operations.[15] Umstead and Denhard argue that ‘in a network structure, capabilities, requirements and other qualities contribute to the influence of each [network] node, and the node with the greatest influence becomes the centre of gravity’.[16] Through a system-of-systems approach, ADF planners can better understand which centres of gravity are the pressure points in any operational plan. The networked approach empowers ADF planners to test and understand how critical factors influence and impact the identified centre-of-gravity nodes. Again, this essay has reinforced the suitability of its proposition that the centre of gravity should be a primary step in the JMAP.

The ADF’s centre-of-gravity process would benefit from an investment in advanced technologies and AI models centred on the JMAP that genuinely provides a complex adaptive system. That ADF planners still rely on spreadsheet software and whiteboards is endemic to an unsophisticated approach to operational planning and the JMAP. As early as 2002, George Mason University and the US Army War College were exploring the creation of an AI system synergised with military strategy research to support centre-of-gravity analysis. Their experimentation significantly improved the centre-of-gravity analysis, with the system learning and adapting from previous inputs. It delivered a model that gave subsequent users highly reasoned centre-of-gravity candidates for consideration.[17] Over the following two decades, computing technologies and AI have achieved enormous improvements, automating many processes that would have previously relied on a ‘human in the loop’, as the JMAP still does.[18] A software-based JMAP, integrated into broader operational planning inputs and Defence databases, would allow for a highly sophisticated planning tool to cater for a fluid and complex environment and handle increasing data feeds. A condition change in any critical factor could be identified by AI that could then detail the relevant impact on a centre-of-gravity network and provide recommendations to operational planners. Suddenly, a linear centre-of-gravity approach becomes highly dynamic, providing relevant and timely inputs into the operational mission and a cognitive competitive edge in the battlespace. Acknowledging the primacy of the centre of gravity in the JMAP could generate the required evidentiary basis for a business case and the required investment.

Overcoming a linear approach through critical and design thinking

Unlike the US Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design, the JMAP affords no relative priority to each step during the training process, and the relative position of the centre of gravity could drive unintended behaviours. Positioning the centre of gravity as one of nine sub-steps within Mission Analysis could unintentionally drive a suboptimal application of intellect and rigour to its analysis. Dr Andrew Jackson, an Australian joint operations planning specialist involved in the second edition’s development, notes that the JMAP is designed with inherent doctrinal flexibility, rendering the centre of gravity’s position a moot point. Jackson argues it is up to the commander and staff ‘regarding the relevant position of the centre-of-gravity analysis within the JMAP’.[19] The inverse consideration is that ADF staff and planners unfamiliar with the JMAP process risk not placing a commensurate amount of intellect or design thinking on the centre-of-gravity analysis. Professor Michael Evans, a Fellow of the Australian Defence College, has previously noted the limitations of the ADF’s joint professional military education, specifically in operational art and, this essay argues by extension, the JMAP.[20] Moreover, whilst Evans’ recommendation for the development of operational cognition within the Australian Defence College has largely been implemented, highly effective centre-of-gravity analysis requires frequent application of the JMAP, which only a portion of students will achieve in their subsequent military.

The current centre-of-gravity analysis and development process within the JMAP risks a lack of critical thinking by focusing on product development. The JMAP’s guidance on critical thinking is limited to a few paragraphs, whereas the US Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design commits an entire chapter. A critical thinking model is provided within Chapter 5, as is guidance on ‘bringing adequate order to complex problems to facilitate subsequent detailed planning’, including the centre-of-gravity analysis.[21] Not only should the JMAP provide more profound guidance on critical thinking, similar to the US Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design, but it should also improve on that comparative planning process by including sub-steps that guide a level of critical thinking. Social sciences author Albert Rutherford defines critical thinking as ‘an attempt to dig deeper … by asking good questions, examining words [and] being sensitive to the context words are written in’.[22] The JMAP notes that a centre of gravity contains many intangible elements at the strategic level, which can require planners to introduce a level of assumption on how and where an adversary may target an operation’s centre of gravity. These assumptions lead to further tension in the Mission Analysis process, with a later sub-step requiring the identification of critical facts and assumptions. Planners can engage in critical thinking to develop a sophisticated analysis of the complex problem of centre-of-gravity analysis that avoids incorrect facts or false assumptions being carried through to decision points, tasks, and task orders. Critical thinking transforms the centre-of-gravity analysis from mechanistic reductionism to a genuinely complex and adaptive system-of-systems that contributes to an effective operational plan.

The continued utility of the centre-of-gravity analysis has been questioned, with fears that an entrenched doctrinal approach and organisational norms have limited the level of cognitive investment by planners. This has led to calls for the centre of gravity to be discarded as a planning tool as it hampers deep thinking and experimentation.[23] Design thinking is just one alternative that has been offered. As a concept, design thinking struggles with a single definition that caters to the diversity of ideas and methods under its label. Design thinking seeks to ‘connect and integrate useful knowledge from the arts and sciences alike, but in ways that are suited to the problems and purposes of the present’.[24] This essay argues that discarding the centre of gravity from the JMAP risks losing the required uniformity to support a system-of-systems approach. Applying design thinking could benefit the centre-of-gravity analysis and development process. As a sub-step in centre-of-gravity analysis, the addition of design thinking could assist in disrupting the JMAP’s current static behaviours through an epistemological frame as proposed by Dr Ben Zweibelson, Director of Design Programs for the United States Joint Special Operations University.[25] Zweibelson contends that the current joint planning processes are ill-equipped for complex systems, such as the complex operational environments the ADF may face. Zweibelson, a strong proponent of an alternate design approach to military planning, suggests alternate analysis methods such as ‘triple loop thinking’.[26] Triple-loop thinking seeks to overcome a linear and systematic approach to a given planning process. Zweibelson’s approach to design thinking is just one of many that centre-of-gravity analysis may benefit from. Horst Rittel, a design theorist, developed the ‘wicked problem’, a concept that the JMAP could adopt.[27] Buchanan has drawn on Rittel’s properties of wicked problems[28] to note that there are no definitive conditions or limits to design problems such as the centre-of-gravity analysis.[29] Together, these approaches are ways to overcome an entrenched doctrinal approach to achieve creative and highly developed centres of gravity.

The application of critical and design thinking to the centre-of-gravity analysis and development is currently challenged by the JMAP’s linear centre-of-gravity process and simplistic examples. The JMAP’s hypothetical example of a centre of gravity is highly reductive. In describing a motorised infantry brigade as a centre of gravity, that being the ‘primary entity that possesses the inherent capability to achieve an objective of the desired end state’, the critical vulnerabilities cover vehicles, petroleum, munitions, command and control systems, aircraft, airfields, and airfield defence systems. The danger in this doctrinal hypothetical example is that an inexperienced planner can infer that all elements of the joint force can be considered a critical vulnerability for any given centre of gravity. It eliminates any need for critical or design thinking. Furthermore, the centre-of-gravity process can inadvertently label all joint force elements as a priority. When everything is a priority, nothing is a priority.[30]

Conclusion

The centre of gravity is a crucial aspect of the JMAP and needs to be a primary step. Dietrich Dörner, an emeritus professor for general and theoretical psychology, provides an interesting analogy that helpfully describes how the JMAP can be incredibly powerful when underwritten by a system-of-systems approach to the centre of gravity in an advanced technology environment. Gone is the ‘steamroller with which one can flatten all problems in the same way’, replaced with an ADF planner with the ‘adroitness of a puppeteer, who at one time holds many strings in his hands and who is able to adapt his movements to the given circumstances in the most sophisticated ways’.[31]

The ADF, and the nation more broadly, find themselves in a highly complex and uncertain security environment. A misstep or miscalculation in centre-of-gravity development, as part of Mission Analysis, can have grave ramifications for the ADF’s operational success. The centre of gravity can be improved by leveraging the comparative planning processes of the US Joint Staff Joint and Coalition Warfighting Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design. Centre-of-gravity analysis should become a primary step in the JMAP before Mission Analysis, strengthened by embedded design thinking principles and powered by advanced technologies and artificial intelligence. Through this approach, the ADF could realise a highly integrated system-of-systems appreciation of threat and own-force centres of gravity. A failure to recognise and invest in the primacy of the centre of gravity will likely result in the JMAP remaining a time-consuming and highly linear process that cannot react quickly enough to maintain operational planning superiority.

Buchanan, Richard. ‘Wicked Problems in Design Thinking’. In Design Issues, 5-21, 1992.

———. ‘Wicked Problems in Design Thinking’. [In English]. Design Issues 8 (1992): 5-21. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511637.

Clausewitz, Carl Von. On War. Edited and Translated by Howard, Michael & Paret, Peter. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976.

Department of Defence. ADFP 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia, 2019.

Dörner, D. ‘The Logic of Failure’. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 327, no. 1241 (1990): 463-73. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1990.0089

Evans, Michael. ‘The Closing of the Australian Military Mind: The ADF and Operational Art’. Security Challenges 4, 2, no. Winter 2008 (2008): 105-31.

Jackson, Aaron P. ‘Center of Gravity Analysis “Down Under”: The Australian Defence Force's New Approach’. Joint Force Quarterly, no. 84 (2017): 81.

Joint Chiefs of Staff. “Depicting the Operational Environment’. Chap. 4 In Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design. Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2011.

———. ‘Understanding the Operational Environment and the Problem’. Chap. 5 In Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design. Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2011.

Martin, Karen. The Outstanding Organization: Generate Business Results by Eliminating Chaos and Building the Foundation for Everyday Excellence. McGraw-Hill, 2012. https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/the-outstanding-organization/9780071782371/ch01.html

Paparone, Christopher R, & William J Davis Jr. ‘Exploring Outside the Tropics of Clausewitz: Our Slavish Anchoring to an Archaic Metaphor’. In Addressing the Fog of Cog: Perspectives on the Center of Gravity in US Military Doctrine, ed Celestino Perez Jr, Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2012.

Park, Dave. ‘Operational Art at the Tactical Level: A Methodology for Center of Gravity Analysis and Identifying Decisive Points for Brigades and Below’. Article. Infantry 101, no. 4 (November 2012): 39-42.

Rittel, Horst WJ., On the Planning Crisis: Systems Analysis of the ‘First and Second Generations’. Institute of Urban & Regional Development, University of California, 1972.

Rittel, Horst WJ & Melvin M Webber. ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning’. Policy Sciences 4 (1973): 155-69.

Rutherford, Albert. Models for Critical Thinking: A Fundamental Guide for Effective Decision Making, Deep Analysis, Intelligent Reasoning, and Independent Thinking. Sydney, NSW: Amazon Publishing Services, 2018.

Scott, Trent. The Lost Operational Art: Invigorating Campaigning into the Australian Defence Force. Land Warfare Studies Centre (Duntroon: 2010).

Strange, Joseph L, and Richard Iron. ‘Center of Gravity: What Clausewitz Really Meant’. Article. JFQ: Joint Force Quarterly, no. 35 (2004): 20-27.

Tecuci, Gheorghe, Mihai Boicu, Dorin Marcu, Bogdan Stanescu, Cristina Boicu, & Jerome Comello. ‘Training and Using Disciple Agents: A Case Study in the Military Center of Gravity Analysis Domain’. 2002, 51.

Umstead, Robert & David R. Denhard. ‘Viewing the Center of Gravity through the Prism of Effects-Based Operations’. Article. Military Review 86, no. 5 (2006): 90-95.

Zweibelson, Ben. ‘Designing Further Afield in Canada and Australia’. In Understanding the Military Design Movement: War Change and Innovation. New York, NY: Routledge, 2023.

———. Triple Loop Learning: Moving Beyond the Pale of the Institutional Limits. Archipelago (2022). https://aodnetwork.ca/triple-loop-learning-moving-beyond-the-pale-of-the-institutional-limits/

1. Carl Von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael and Paret Howard, Peter (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 595.

2. Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, 3-6 (Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia, 2019).

3. Mission analysis is the second step in the JMAP and is the most substantial in terms of the breadth of issues considered and scope and detail out output generated.

4. The threat centre of gravity is assessed in the Joint Intelligence Preparation of the Operational Environment, which is an external process, generally conducted by Intelligence personnel, that provides as an input into the JMAP.

5. Trent Scott, The Lost Operational Art: Invigorating Campaigning into the Australian Defence Force, Land Warfare Studies Centre (Duntroon, 2010), 102.

6. Clausewitz, On War, 595.

7. Joseph L. Strange and Richard Iron, ‘Center of Gravity: What Clausewitz Really Meant’, Article, JFQ: Joint Force Quarterly, no. 35 (2004).

8. Department of Defence, Short ADFP 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, 3-8.

9. Department of Defence, Short ADFP 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, 3-10.

10. Department of Defence, Short ADFP 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, 3-9.

11. Joint Chiefs of Staff, ‘Depicting the operational environment’, in Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2011).

12. Department of Defence, Short ADFP 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, 3-13; Joint Chiefs of Staff, ‘Depicting the operational environment’, IV-5.

13. Dave Park, ‘Operational art at the tactical level: A methodology for center of gravity analysis and identifying decisive points for brigades and below’, Article, Infantry 101, no. 4 (November 2012): 41.

14. Department of Defence, Short ADFP 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, 3-13.

15. The ADF does not subscribe to ‘Effects Based (Approach to) Operations’ and uses the term ‘effect’ in a broad, generic sense. Notwithstanding, the principles could be applied to the JMAP.

16. Robert Umstead and David R. Denhard, ‘Viewing the Center of Gravity through the Prism of Effects-Based Operations’, Article, Military Review 86, no. 5 (2006): 92.

17. Gheorghe Tecuci et al, ‘Training and using DISCIPLE agents: a case study in the military center of gravity analysis domain’, 2002, 66.

18. ‘Human in the loop; refers to a process that inherently requires human interaction to provide input to complete the loop.

19. Aaron P. Jackson, ‘Center of gravity analysis “down under”: the Australian Defence Force's new approach’, Joint Force Quarterly, no. 84 (2017): 84.

20. Michael Evans, ‘The Closing of the Australian Military Mind: The ADF and Operational Art’, Security Challenges 4, 2, no. Winter 2008 (2008): 129.

21. Joint Chiefs of Staff, ‘Understanding the operational environment and the problem’.

22. Albert Rutherford, Models for critical thinking: A fundamental guide for effective decision making, deep analysis, intelligent reasoning, and independent thinking (Sydney, NSW: Amazon Publishing Services, 2018), 13.

23. Christopher R. Paparone and William J. Davis Jr, ‘Exploring outside the tropics of Clausewitz: Our slavish anchoring to an archaic metaphor’, in Addressing the fog of COG: Perspectives on the center of gravity in US military doctrine, ed Celestino Perez Jr (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2012).

24. Richard Buchanan, ‘Wicked Problems in Design Thinking’, Design Issues 8 (1992): 5-6, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1990.0089.

25. Ben Zweibelson, ‘Designing further afield in Canada and Australia’, in Understanding the military design movement: War change and innovation (New York, NY: Routledge, 2023), 306.

26. Ben Zweibelson, Triple loop learning: Moving beyond the pale of the institutional limits, Archipelago (2022),https://aodnetwork.ca/triple-loop-learning-moving-beyond-the-pale-of-the-institutional-limits/

27. Horst WJ Rittel and Melvin M Webber, ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning’, Policy Sciences 4 (1973).

28. Horst WJ Rittel, On the Planning Crisis: Systems Analysis of the ‘First and Second Generations’, (Institute of Urban & Regional Development, University of California, 1972), 392-3.

29. Richard Buchanan, ‘Wicked Problems in Design Thinking’, in Design Issues (1992), 16.

30. Karen Martin, The outstanding organization: generate business results by eliminating chaos and building the foundation for everyday excellence (McGraw-Hill, 2012), https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/the-outstanding-organization/9780071782371/ch01.html

31. Dietrich Dörner, ‘The logic of failure’, Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 327, no. 1241 (1990): 24, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1990.0089

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.