Let the War (Games) Begin!

Two gaming enthusiasts roll the dice at the Australian Command and Staff College to demonstrate how wargames can be a creative engagement and learning tool that enhances the learning experience.

In 2021, we both posted to the Australian War College as Directing Staff on the Australian Command and Staff Course (ACSC). We knew each other from our time together as course members in 2014 and we both shared a love of wargaming. While our journey to get wargaming implemented as part of the curriculum is motivated by a desire to enjoy our favourite hobby in work time, there is also a wealth of useful information that highlights the relevance of Wargames as an Educational Tool.

As the Australian Defence College is exploring the use of games as part of Joint Professional Military Education (JPME), this article aims to contribute to the discussion about how the Australian Defence Force can deliberately incorporate games throughout all levels of JPME. For us the advantages of wargames for JPME are clear. Wargames are inherently engaging as they are adversarial in a high-immersion, safe-to-fail environment. The participants make decisions and deal with the consequences during the game. Participants can attempt, as Clausewitz would say, ‘to compel our enemy to do our will’. As an experiential learning technique, it is highly salient to the JPME Continuum’s 70:20:10 model.[1] So, let us take you on our journey.

Part 1 - Plan 1919 and ACSC’s Operations 1 Module

Our first stop on the journey was selecting Plan 1919: Fuller's Plan to End the Great War to complement the learning from the Australian National University’s Operations 1 Module. This module was initially focused on the First World War and this game was selected to try to educate course members on the problems that commanders faced in the First World War. Plan 1919 is a commercially available board game between two opponents. The game allows players to explore the 'what if' scenario if the 1918 Armistice had not been signed. The Entente attempts to enact noted British Army strategist JFC Fuller's plan for 1919 offensives. One participant plays as the Entente, winning if they can take Germany's strategically important cities. The other participant plays as Germany, and wins if they can hold off the Entente for 20 game turns. The rules simulate the historical conditions and reward the use of the tactical innovations of the time, such as air support, massing tanks and the use of combined arms warfare.

Generally, we had 10-12 players split between two boards (four teams of three players) and we played after the curriculum had finished for the day. There were a host of good lessons and context that were gained from the game as a result of choosing a wargame linked directly to the Operations 1 Module. The game provided a number of reflective insights into areas such as WWI tactics, resources and avenues of advance. As one course member wrote, [Plan 1919]‘caters more to people who 'learn by doing’, who do not necessarily relate well to the university style of learning’.

In terms of the game itself, the rules are relatively light (and therefore accessible to new players). These players still need some pre-reading to understand how the rules reward and constrain each side. At the same time, the game takes hours to play out. Even with preparation work beforehand, the conduct of the activity generally takes around four hours.

Part 2 - Mrs Thatcher’s War and ACSC’s Operations 2 Module

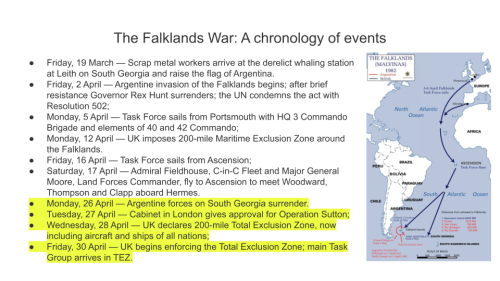

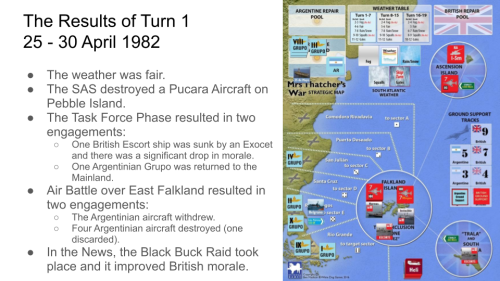

Our second stop on the journey was selecting Mrs Thatcher's War to complement the Operations 2 Module. This module covers a series of post-Second World War conflicts including the Falkland Islands War. This board game was selected to try to add context to a syndicate discussion, which was part of the module.

Mrs Thatcher's War is a solitaire game based on the Falkland Islands War, which puts the player in the role of the British Task Force Commander, trying to balance strategic and tactical considerations while commanding an amphibious operation. Board Game Geek has written an excellent review of the game. This time, we had both the physical version and the 'virtual' version hosted on a digital tabletop application called Vassal. Vassal is a game engine for building and playing online adaptations of board games and card games. This allows the game to be played interactively on a smart board in front of our syndicates.

The syndicate discussion (1 hour and 30 minutes) started with a chronology of the ‘real events’ and what had happened in the game. The game had been played by the two of us as directing staff over a number of turns so that the maritime task group was ready to recapture the Falkland Islands to maximise the learning benefit. These products are displayed below.

The syndicate was divided into the task group commander, a land commander, the carrier air wing commander and amphibious task group commander. This enabled a debate about what was the main effort by turn and how to resource it. The problem facing the task group commander was a lack of aircraft. Once again, the results for the course members were excellent. In addition, there was sufficient ‘fog and friction’ built into the game so that it was hard to pre-determine the results of the group’s allocation. This game enabled the ability to think critically about this problem and reflect on the decisions of Admiral Sir John ‘Sandy’ Woodward, who commanded the task force. There were lessons about war that were wider than this specific conflict too. As one course member wrote, ‘the game really highlighted the impact of unpredictable factors (such as weather, combat losses, government actions) and the impact this had on decision making. While the game was specific, this outcome was relevant to a lot of the wars discussed…’.

Part 3 - ACSC’s Perry Group Elective

Our third stop on the journey was with the Perry Group. This is a voluntary elective for ACSC course members, and its objectives are:

- Hone a more forward-thinking mindset, using science fiction, that can be applied to futures-oriented institutional tasks.

- Provide the opportunity to research, and develop a ‘useful fiction’ article on, future Australian Defence Force capability outside of the normal Australian War College continuum for the Chief of Defence Force.

- To excite students and reinforce their personal love of learning about the profession of arms.

There were four teams of seven course members, paired with a sponsor from the ADF to answer the following questions:

- What should be Defence’s strategy for the utilisation of the space domain in 2040?

- What should be Defence’s strategy for the utilisation of the information and cyber domain in 2040?

- What challenges and opportunities does AI and automation present for Defence out to 2040?

- By 2040, what security risks will climate change present to future Defence operations and business, and how should we plan for them

To ensure the articles developed by the four teams were ‘useful fiction’, we initially envisaged using the ‘Matrix’ wargame method to support exploring answers to the four questions above. We were familiar with Tom Mouat’s ‘Practical Advice on Matrix Games (Version 13). The key strengths of the Matrix Wargame method for the Perry Group are:

- The chances of success/failure are determined by the strength of the teams' arguments.

- It is suited to complex issues.

- The game generates a credible narrative that should support the development of useful fiction.

By the time we came to the wargaming section of the elective, the four teams’ articles were sufficiently developed so that it was difficult to tailor a wargaming scenario to the specific narratives that the teams had created. Instead we chose to ‘Red Team’ the articles using the excellent Red teaming: a guide to the use of this decision-making tool in defence, developed by the Ministry of Defence Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre (DCDC). This was still useful to the teams. As one course member wrote: ‘Wargaming was a good way to test ideas. It might be worthwhile moving that a bit earlier in the program, with the expectation that stories would still be in quite the draft state, to test ideas and assumptions early on’. The main lesson from this stop on the journey was the need to run the wargaming session earlier in the elective before the teams had developed their stories. Games we could have considered based on the questions were:

- Information Warfighter Exercise wargame developed by RAND.

- Sweeping Satellites developed by Mark Flanagan & Ian Robinson

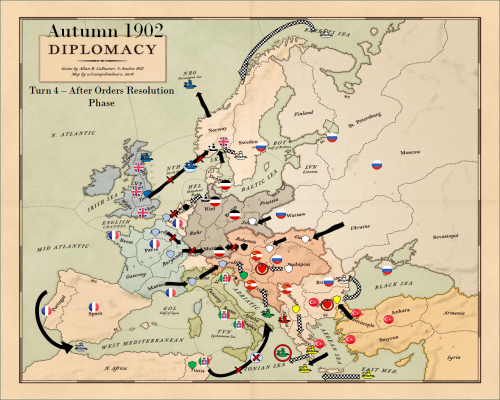

Part 4 - Diplomacy

Our fourth stop on the wargaming journey was the introduction of the game Diplomacy. The aim was to find a game to complement the Australian Defence and Security Policy module. Diplomacy would have been equally relevant to the strategy of the operations module as it is set in 1901. Playing as one of Europe’s great powers, a player’s goal is to achieve hegemony. Through a combination of conquest, alliances and diplomacy, players compete to control key supply centres. The first power to control 18 of the 34 supply centres wins.

The players consisted of ACSC course members and staff, who were free to discuss plans and strategies. Alliances and deals were made openly and in secret. Following a period of diplomacy, each nation submitted orders for their units. Orders were simultaneously revealed via a PowerPoint slide embedded in an email (by this stage we were in the ACT COVID-19 lockdown that commenced in August 2021), and armies and fleets were moved. While alliances and agreements are needed to succeed, in the end the national interest will trump relationships. The inaugural stab-in-the-back trophy was awarded to the French players in 2021. This is not a good game for earlier in a course, as it can cause some loss of cohesion and trust between players. It was important as the Ottoman Empire player that I put my figurative fez on while engaging with course members acting as the representatives of the Tsar.

Part 5 - The Alternative Joint Capability Tour

The final stop on the journey was an opportunity to formally introduce wargaming to the ACSC curriculum once it looked like some components of the Joint Capability Tour (JCT) would be cancelled due to COVID travel restrictions. The JCT involved a week in the ACSC calendar dedicated to visiting frontline units, elements of the national support base and defence industry. At first, we had a manageable 24 players when the Sydney component of the tour was cancelled. Later we appeared to be on the brink of catastrophic success when all tours were cancelled and we needed to develop a wargaming program for 192 course members. In the end, the Canberra lockdown forced us to trial virtual wargaming. There were two games that supported virtual delivery and each was played over a four-hour period. The first game was Fleet Marine Force.

Fleet Marine Force (FMF) is a high-tactical educational wargame pitting a US Marine Corps multi-domain task force against the People’s Liberation Army in the Indo-Pacific in the 2025 timeframe. This game provided a valuable introduction to the near future operational environment, and technologies in all-domain warfare including cyber and space effects. The players were afforded a valuable opportunity to practice joint planning. The session was facilitated by Adjunct Professor Sebastian Bae, from the Georgetown University Wargaming Society and Non-Resident Fellow at the Krulak Centre. Each team was mentored by a member of the ACSC directing staff. Gameplay platform used was Steam and the teams communicated with each other and the facilitator using the communications platform Discord.

FMF is a good platform for practising the mission analysis process, but models a level of war below the operational level of ACSC’s JPME outcomes. It does, however, provide some insight into capabilities in all five domains and is therefore very useful for course members without a great deal of joint warfighting exposure. It is also future focused, providing some links to the ACSC Capability module. It would be easy to modify the content to model Australian capabilities from the Integrated Investment Program and add Australian-focused scenarios in our immediate region.

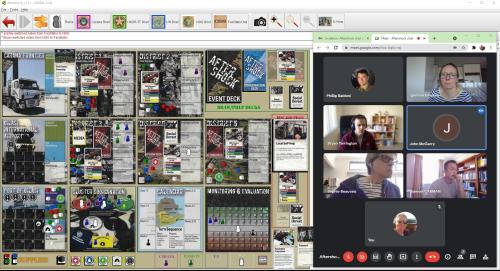

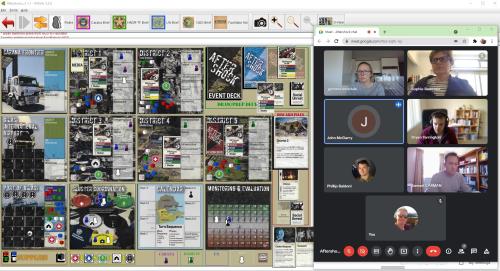

The second virtual game was Aftershock: A Game of Humanitarian Crisis. This game was specifically designed for professional education about humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) operations. It explores the emergency and early recovery phase of a complex humanitarian crisis in a fictional country. Players take the role of a HADR taskforce, UN agencies, host nation, and non-government organisations. The JPME outcomes included the exploration of inter-agency cooperation and the strengths of different agencies during different periods of a crisis. The two parallel games were facilitated by Director of Wargaming and the Strategic Policy Division, Mr Darren Huxley, and Air Vice-Marshal (retd) John McGarry. They were both part of the well-established group of experienced and credible proponents in the Department of Defence who were eager to assist in any application of wargaming relevant to ACSC (educational, analytical, wargaming for experimentation, wargaming for force design etc). Gameplay platform was Vassal and we used the communications platform Google Meet, as it was the main collaboration tool on ACSC.

Aftershock provides good insight into the complexities of humanitarian operations and the United Nations. Playing it with participants from other government agencies or NGOs (potentially aligned with Joint Exercise 3 within the Joint Operation module) would provide an excellent platform for course members to have quality contextualised and innovative interaction with those partners.

An ‘upscaled’ version developed for Defence Strategic Studies Course (Paradissio) could provide a better vehicle for learning about inter-agency operations at the operational and strategic levels. At the same time, Paradissio adds a layer of complexity and requires more time to teach and play. The ADF owns the intellectual property rights to Paradissio, giving the opportunity to amend the rules and product to suit the ACSC JPME outcomes.

Overall, we both learnt two useful lessons about facilitating wargames virtually. The first concerned testing and rehearsals. The literature on educational wargaming generally emphasises that training of facilitators and rehearsals are key to success. When using virtual platforms, this was even more important. We also ‘stress-tested’ the applications using real-time conditions such as the maximum number of players. This revealed some issues with platforms that were not envisaged when they were tested by a single player, for example. These virtual rehearsals should replicate the conduct of the game as closely as possible.

The second lesson was the importance of a ‘comms check’. This routine activity in a military context proved useful to prepare for gaming. The literature on educational wargaming virtually highlights that it requires more time to set up and conduct a wargame than an in-person activity. This was certainly the case for the FMF and Aftershock sessions we facilitated. The use of a pre-game session with participants to ensure connectivity and familiarity with the platforms was vital. Participants were given written instructions prior to the events, with confirmation conducted via a virtual session before the games. These measures proved vital to ensure that the time allocated to the wargame was used most effectively for learning rather than addressing technical issues. Ensuring participants and facilitators were prepared also allowed assistant facilitators to concentrate on helping participants who signed up on the day of the event.

Conclusion

The key lessons we identified during our wargaming journey within the Australian Command and Staff Course can be summarised into the following key points:

The journey for us both has been extremely rewarding. We have demonstrated that wargaming complements the ACSC curriculum and is aligned to the JPME outcomes. We are now connected to a well-established group of experienced and credible ADF and international wargaming proponents. We have also introduced about 20 per cent of the ACSC 2021 course members to the benefits of wargaming.

- Playing wargames directly supports JPME at ACSC.

- Choose wargames that complement the academic program to provide richer engagement with the academic material.

- Implement wargames early in the course.

- Allow the course members an opportunity to ‘play’ before the formal sessions.

- Use experienced facilitators to help maximise the educational value of the game.

- ‘Stress test’ the wargame in the environment in which it will be played.

We have learnt a lot more about the wargames Plan 1919, Mrs Thatcher’s War, the Matrix method, Diplomacy, FMF and Aftershock. Of the greatest importance, we have conducted our favourite hobby in work time while introducing others to the value of wargaming as an experiential learning method that complements traditional classroom lecture and seminar work. We hope that our work forms the start of the War College’s continuing journey for using wargaming in its education and training programs.

Phil Baldoni remains as part of the Directing Staff in 2022 and with the support of the Director of ACSC he intends to integrate wargaming more fully into the ACSC program with a game to complement each module. Mark Mankowski is off to Headquarters 1 Division, where he intends to take FMF with him to help his team to explore the evolving character of war.

[1] 70% experience, 20% exposure, 10% education. See the JPME Handbook.

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.