Introduction

The Australian Government adapts its defence policies to meet the perceived challenges and threats posed by the country’s geopolitical, geoeconomic, and domestic circumstances. Policymakers are shaped by evolving factors and conditions within the national strategic landscape including the capability, intent, and proximity of perceived threats, the balance of national interests, technology, and domestic priorities. However, five enduring characteristics in Australia’s national strategic context perpetually inform defence policy. Enduring characteristics are factors, conditions and assumptions that have not changed since Federation in 1901 but continue to drive security and defence policy.[1]

This article uses the five enduring characteristics of Australia’s national strategic landscape to consider the similarities between Australia’s modern strategic context to the conditions faced by policymakers and military planners in World War II, particularly in 1942. The year 1942 is important because it represents the only period in Australia’s history where the national security system was operating against a perceived existential military threat.[2] Australian and Allied responses to the threat of Japanese invasion offer a valuable insight into how policymakers and strategists can manage the inherent limitations and opportunities afforded by the five enduring characteristics in the modern context.

An Island Surrounded by Islands

The first enduring characteristic of the national strategic landscape is that Australia is a continent-island, surrounded by non-adversarial archipelagic countries.[3] As the world’s largest island and the sixth largest country, Australia has several defensive advantages.[4] Any potential adversaries wishing to launch an attack or invade the continent require sufficient long-range air, ground, and maritime assets to reach even the sparsely populated northern parts of Australia, let alone the resource-rich areas in the south.[5] Any adversary that attacks or invades the continent must establish a forward presence in the Southwest Pacific archipelago to avoid long and vulnerable lines of supply and communication.[6] Australia is too large and inhospitable for a dismounted ground attack so potential invaders are confined to the limited airfields, roads, and railways that connect Australia’s northern communities.[7]

Geography can also be a disadvantage. Australia is approximately 12,000 kilometres from its closest allies, delaying assistance in the event of an invasion.[8] The coastline is extensive, so an enemy can land a sizable force in an undefended portion of the continent, and the limited interior lines of communication make any ADF counterraid or counter-attack time-consuming and predictable.[9]

In 1942, the US Army chose Australia as its base of operations in the Pacific due to geographic circumstance, rather than a prearranged contingency plan.[10] Australia was large enough to host multiple, dispersed American airfields, close enough to serve as base to project force against Japan’s main axis of advance in the Pacific, but far enough from Japanese-held territories that reinforcements could be sent from the United States without fear of interdiction by Japanese aircraft or shipping.[11]

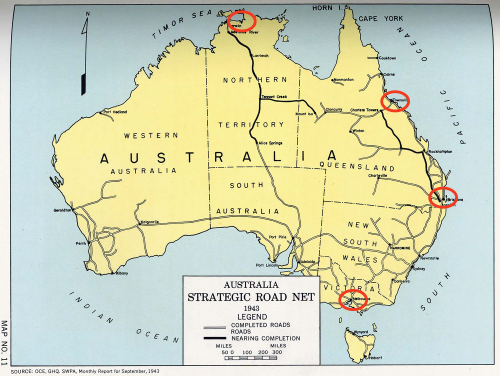

Australia’s geography provided many challenges for American operational planners. The initial build-up of forces was slow because the transit time between the United States and Australia by ship was over two months.[12] The main disembarkation location for US troops arriving in Australia was in Melbourne, however the primary base depot was in Brisbane, the secondary base depot was in Townsville, and the advance depot was in Darwin.[13] Overland transport in 1942 was highly underdeveloped, so movement between these locations was laborious and subject to good weather.[14]

Location of US Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA) Logistic Nodes February 1942.[15]

In the decade leading to World War II, the Australian Government paid little attention to its own geographic limitations and advantages.[16] It did not consider any foreign powers capable of invasion, and the ongoing investment of neutral or friendly European powers in the inner arc of islands to Australia’s north contributed to a broader sense of security.[17] After Germany invaded the Netherlands and France in 1940, Australian politicians became concerned that the Japanese might take advantage of the weakened or exiled governments and seize islands of strategic interest in the Southwest Pacific.[18] To mitigate the threat of a hostile force occupying the islands to Australia’s immediate north, the Australian Government deployed the 8th Division and elements of 6th and 7th Divisions into the archipelago in December 1941 and February 1942.[19]

Australian Army Chief of the General Staff, Lieutenant General Vernon Sturdee, criticis ed the government’s strategy to ‘hold numerous small localities with totally inadequate forces which are progressively overwhelmed by vastly superior forces’.[20] In February 1942, he advocated for the return of all Australian divisions to take advantage of the country’s geographic strengths.[21] Despite Sturdee’s advocacy, the Australian Government remained committed to a forward defence posture, a decision which resulted in over 20,000 Australians being taken as prisoners of war between January and April 1942.[22]

The 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) suggests that Australia is no longer protected by geography as military modernisation means that potential adversaries can project power across greater ranges in the maritime, land, air, space, and cyber domains.[23] Whilst it is true that modern weapons can strike deep into Australian territory, ‘the application of physical force remains an inherently special business … and distance remains … a decisive factor in the ability to launch and sustain military operations’.[24] Australia’s vulnerability to invasion remains low because even Australia’s greatest strategic rival, China (the People’s Republic of China, or PRC), does not have the resources to launch and sustain a large offensive from the Asian continent.[25] However, with access to military bases in the Southwest Pacific or Southeast Asia, the People’s Liberation Army could challenge control of Australia’s air and sea approaches and build capacity for military operations on the continent.[26]

Population Density and Resource Constraints

The second enduring characteristic of the national strategic landscape is that Australia has asmall population and economy relative to its geographical size. With a population of 3.3 per square kilometre, it is one of the least densely populated countries in the world, followed only by Namibia, Mongolia, and Greenland.[27] From a gross domestic product (GDP) density perspective, Australia was in the bottom third of a 2018 table ranking the world’s countries by GDP per unit of land area. GDP per unit of land area is an important measure of economic prosperity because it considers the inherent value of land and the relative ability of a nation to generate wealth within its territorial boundaries.[28]

Australia had a GDP of US$186,000 per square kilometre, compared to the PRC which had a GDP of $US1,449,000 per square kilometre and the United States with $US2,245,000 per square kilometre.[29] Australia’s low GDP density is attributed to its topography, limited perennial and navigable waterways, and the habitability challenges of northern and central areas.[30] Its limited population and economic capacity affect not only the size and structure of the ADF, but also the nation’s ability to sustain a wartime economy.[31] These challenges affected political and strategic decisions in 1942 and have continued relevance for defence policymakers today.

Australia’s reported population on December 31, 1941, was 7,137,221, equating to a density of less than one person per square kilometre.[32] One of the key challenges facing the Australian Government in 1942 was how best to harness the population to defend the country’s interests. Soon after losing the 1941 election, former Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies stated:

When a war goes to the root of national existence all our conceptions of it have to be reorganised … Many thousands of men must go into the Army, the Navy, the Air Force. Many thousands more must make munitions; build aircraft; manufacture equipment and clothing; grow, prepare, and transport food; take their place in an enormous mechanism which may start with the ploughing of 300 acres of land in the wheat country and end with the distribution of bread to the fighting man in the battle front.[33]

The government introduced legislation in late 1941 requiring all people over the age of 16 to register with the Manpower Priorities Board for potential service in either the military or in an essential civilian industry.[34] The Manpower Directorate, established in January 1942, identified the need for an additional 318,000 people for the military and essential services. However, by August 1942, the Directorate had only filled 105,000 of those positions.[35]

Australia’s labour shortages and limited productive capacity also impacted US military operations and strategy in the region the US and Allies had now designated as the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA). USAFIA Colonel Stephen Chamberlin noted the difficulties of establishing forward operating bases for offensive operations against Japan in a letter dated February 26, 1942:

There is a total absence of labor in Australia. We have pushed and shoved and cried to get labor into the Northern Territory in order to develop Darwin and to improve road and railroad conditions, but all of that energy has been futile … We require thousands and thousands of labor to develop a communication route satisfactorily for any kind of operation in this country.[36]

Upon assuming command of SWPA in March 1942, US Army General Douglas MacArthur campaigned for additional resources and manpower from his senior commanders.[37] Although he was successful in obtaining some US reinforcements for the offensives in northern New Guinea commencing in August 1942, Australian units still comprised the bulk of the ground forces.[38] MacArthur had hoped to complete the New Guinea operation within a matter of weeks, but the campaign was hampered by a determined enemy, competing priorities, harsh conditions, disease, and shortages in manpower, supplies, shipping, aircraft, and weapons.[39]

Australia’s 2024 population of 27 million people is more than 3.7 times larger than the 1942 population.[40] However, the relative size of the population (as a percentage of global population) has grown by less than 0.02 per cent. This means that whilst the Australian Government can potentially mobilise a greater number of people in the event of war, it is also likely to fight a much larger adversary than it did in 1942. For example, the relative size of the Japanese Empire in 1938 was 5.98 per-cent of the global population or 71.9 million people. However, in 2022 the population of China (minus Taiwan) was 17.64 per-cent of the global population, or 1.41 billion people.[41] Australia also has an ageing population, with 17 per cent aged over 65, compared to just over 7 per cent in 1938.[42] Unemployment has dropped from approximately 10 per cent in 1939, to an average of 4 per cent in 2023, reducing the percentage of recruitable labour for defence-related industries.[43]

Continental Depth

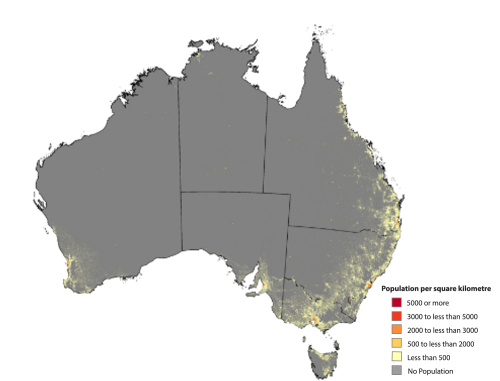

The third enduring characteristic of Australia’s strategic landscape is that the nation’s population, manufacturing capacity, and critical infrastructure are concentrated in the southeast corner of the country.[44] This disposition provides Australia with strategic depth because key resources ‘are very hard to reach for combat aircraft operating even from bases in the inner arc of islands, let alone from the home bases of major powers’.[45] Despite the advantages of depth, the population expects the ADF to defend the whole continent, and the tyranny of distance increases the government’s basing, infrastructure development, force projection, and sustainment costs.[46]

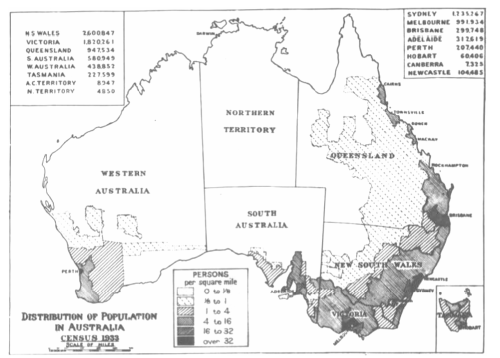

The illustration below shows population distribution, based on the 1933 census, with most population centres on the coastal fringes and agricultural areas in the southeast corner.[47] The historical factors contributing to this clustered development include rainfall variability, the location of artesian basins and perennial waterways, the location of minerals, oil, and coal, and the arability of the land.[48] Both Australian and American World War II strategists developed plans in 1942 that considered the abandonment of northern and central areas to focus on the defence of the southeast corner of the country.

Distribution of Population in Australia Census 1933.[49]

The first plan was developed by the Australian Commander-in-Chief Home Forces, Major General Iven Mackay, on February 4, 1942.[50] At the time, the 6th and 7th Divisions were returning by sea from the Middle East and the first large contingent of US forces had yet to arrive in Australia. The only forces available to defend the continent were poorly equipped and trained militia divisions, an armoured division with few tanks, and support units from the AIF.[51] Mackay’s plan acknowledged that there were insufficient resources to defend the whole continent and recommended a concentration of military units to defend the most important economic and population centres between Melbourne and Brisbane.[52] He noted that dispersing the limited available resources for the defence of Australia would lead to defeat in detail, and that ‘it may be necessary to submit to the occupation of certain areas of Australia by the enemy should local resistance be overcome’[53] The arrival of additional US forces and the return of the AIF Divisions later in February altered the strategic situation, so the plan was never implemented.[54]

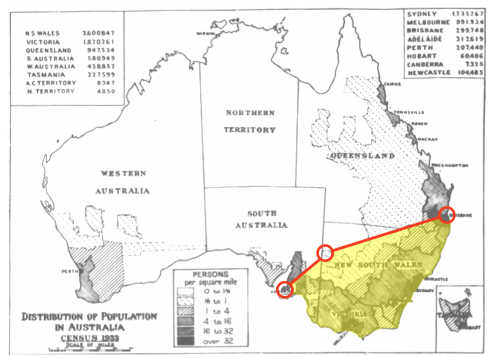

The second plan was developed by the Operations Section of General Headquarters SWPA on October 31, 1942. Throughout late October, MacArthur was worried that if Admiral Nimitz’s Guadalcanal campaign failed, Japanese forces would renew their efforts to establish a military base in South Papua for an eventual strike in Australia.[55] The Petersburg Plan was ‘an outline plan for the redistribution of Allied Forces, SWPA, in [the] event of Japanese success in the Solomon Islands’.[56] The aim of the plan was to protect the vital military areas of the continent south and east of a line linking Brisbane-Broken Hill-Adelaide to ensure Australia could continue to serve ‘as a base for offensive operations against Japan’.[57] The plan describes a conditions-based, phased withdrawal of Allied forces from New Guinea to the main population centres in Australia based on shipping availability and projected enemy actions.[58] Allied success on Guadalcanal in early 1943 meant that the plan was never executed, however the SWPA staff were poised to implement a defence-in-depth posture if the strategic conditions had required it.[59]

Petersburg Plan Vital Area of Military Concentration.[60]

The disposition of Australia’s population and industry today resembles that of the pre-World War II era. Despite the risks posed by the modern strike ranges of potential adversaries, the ADF does not prioritise defence of the southeast corner of the continent.[61] The 2023 DSR instead recommends ‘a key line of forward deployment for the ADF [that] stretches across Australia’s northern maritime approaches’, but acknowledges the ‘need for depth in force posture’ through a network of bases from Adelaide to Brisbane.[62] It also encourages investment in northern air bases and fuel facilities, south to north roads, maritime, air, and rail distribution networks.[63]

Distribution of Population in Australia Census 2021.[64]

Prioritising northern bases is consistent with Australia’s strategic culture, in that policymakers have always looked to defend the continent as an island first.[65] Depth has typically meant deploying expeditionary ground forces to the Southwest Pacific or Southeast Asia, or denying passage of potential adversaries across the sea-air gap to Australia’s north.[66] As the DSR demonstrates, like their 1930s predecessors, modern policymakers and strategists are not focused on defending population centres and resources in a land campaign in the southeast corner of Australia.[67]

Maritime Trade and Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs)

The fourth enduring characteristic of the national strategic landscape is that policymakers and the public consider maintenance of Australia’s SLOCs to its trade and ally partners as being critical to national security.[68] Secure trade routes are vital for economic prosperity, and politicians acknowledge that ‘even limited attacks on merchant ships trading with Australia could generate economic uncertainty, upward pressure on insurance rates and demands for maritime protection’.[69] Secure SLOCs also ensure the interconnectedness of the country with its security partners, enabling the two-way transfer of equipment, supplies, and personnel.[70] Due to the extended supply routes between Australia and its historical alliance partners, politicians and military personnel, both in World War II and in the modern context, must consider the risks of maritime interdiction in their strategic planning.[71]

Exports accounted for 35.6 per cent of Australia’s net production in the three years before the start of the World War II.[72] Farm products were the highest traded goods, with wool ‘providing about half the value of farm exports and about 40 per cent of the total value of exports’.[73] However, by 1942, due to the security situation in the Mediterranean and Atlantic Oceans, and a lack of global shipping, Australia found most of its overseas markets threatened and, in some cases, completely inaccessible.[74] In order to maintain the war effort and provide for the civilian population, the Australian Government diversified the economy, put strict measures in place to control primary production, introduced price caps, and increased domestic manufacturing.[75] These measures enabled Australia to successfully fund its wartime economy despite significant reductions in trade.[76]

Although sea trade was not vital for Australia’s economic wellbeing in 1942, SLOC security remained a key component of the nation’s defence strategy. One of Japan’s objectives in 1942 was to prevent Australia from becoming a base for future Allied offensive operations in the Western Pacific by isolating it from the United States.[77] In response, Allied political and military leaders developed a defensive strategy to protect SLOCs between the east coast of Australia and the west coast of the United States.[78] This link provided SWPA commanders with the ability to leverage American industrial capacity and manpower to build up logistics and improve the combat ratios for offensive operations against the Japanese in the second half of 1942.[79]

The 2023 DSR identifies the disruption of SLOCs as a potential threat to national security due to the country’s reliance on trade.[80] In September 2023, Australia’s exports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP was 24.9 per cent.[81] The resources sector accounted for 61.5 percent of exports, the rural sector accounted for 11.1 per cent of exports and approximately 99 per cent (by weight) of Australian trade was carried by sea.[82] As an island positioned at the intersection of the Indian, Pacific, and Antarctic Oceans, Australia is vulnerable to any conflict that disrupts or imposes additional costs on maritime transportation.[83]

The Junior Partner

The final enduring characteristic of the national strategic landscape is that Australia considers itself an important but junior partner in its most important bilateral security agreement.[84] Before Japan entered World War II, the senior ally in this security arrangement was Great Britain.[85] However, due to the military circumstances of late 1941, Australian Prime Minister John Curtin found it necessary to seek security elsewhere, stating, ‘without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom’.[86] The alliance between Australia and the United States has enjoyed longstanding bipartisan support in both countries since its inception, although its relevance and importance has fluctuated over time.[87] The evolution of Australia’s relationships with Great Britain and the United States in WWII has had a lasting impact on strategic culture.[88]

The Australian Government realised how vulnerable it was as the junior partner in its security agreement with Great Britain when Singapore fell to the Japanese Imperial Forces on February 15, 1942.[89] Curtin considered Britain’s failure ‘to defend Singapore to the utmost’ as ‘an inexcusable betrayal’.[90] Soon after the fall of Singapore, British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, diverted Australian forces returning from the Middle East towards Burma for the defence of Rangoon.[91] The Allies surrender in Singapore and the diversion of Australian forces to Burma are evidence of a divergence of interests between Australia and Great Britain in early 1942. These two examples underscore the reality facing Australian politicians—they could no longer rely on Britain’s defence capabilities and Australia would need to look to a different nation for support.[92] Fortunately for Curtin, the divergence of national interests between Australia and Great Britain coincided with the convergence of national interests between Australia and the United States.[93]

Australia’s uneven partnership with America began in March 1942, when the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff appointed MacArthur as the Supreme Commander of the SWPA.[94] The Australian Prime Minister agreed to subordinate all Australian forces to MacArthur in a directive stating, ‘at the request of a sovereign State you are being placed in Supreme Command of its Navy, Army and Air Force, so that with those of your own great nation, they may be welded into a homogenous force’.[95] According to historian David Horner, “’this was a substantial abrogation of Australian sovereignty’, but necessary given the threat, political circumstances, and limitations of the Australian military.[96]

Although the Pacific theatre was not the priority for the Allies in 1942, the United States employed enough military force in the SWPA to secure and defend Australia during this critical period.[97] The United States also established important logistic and intelligence hubs in Australia to facilitate and support joint operations.[98] US aircraft operating from Australian airfields were able to establish regional air superiority, and the presence of American naval forces, including aircraft carriers, helped secure sea lanes and prevent Japanese landings in Papua.[99] Some authors have suggested that it was never US intent to establish a longstanding alliance with Australia in 1942, and that the temporal relationship was a matter of military convenience.[100] Whether accurate or not, modern discourse widely accepts that the US military was instrumental in protecting Australia and celebrates 1942 as the year the United States became the pillar of Australian security.[101]

The 2023 DSR reaffirms the significance of the United States-Australia alliance as being ‘central to Australia’s security and strategy’.[102] It also acknowledges that America ‘is no longer the unipolar leader of the Indo-Pacific’ and that Australia needs to ‘develop capabilities to unilaterally deter any state from offensive military action against Australian forces or territory’.[103] The ANZUS Treaty does not guarantee an American military response in the event Australia is attacked or invaded and there is no specific or detailed coordination between the two countries for such an eventuality.[104] Furthermore, the events of 1942 continue to serve as a reminder to policymakers that the capability and willingness of allies to provide support to Australia are contingent on their own strategic priorities and obligations.[105]

Conclusion

Australian and Allied responses to the threat of Japanese invasion in World War II offer insights for managing the inherent limitations and opportunities afforded by the five enduring characteristics of the national strategic landscape. World War II planners had to consider the nation’s expansive geography, critical SLOCs, demographic limitations, manufacturing capacity, partner’s priorities, and the concentration of critical infrastructure in the southeast corner of the country in the development of their strategies. Ultimately, Allied forces were able to defend Australia in 1942, but only with considerable supplementation by US resources. Although much has changed since World War II, enduring characteristics remain relevant and worthy of consideration in the contemporary context.

1 Paul Dibb, “The Return of Geography,” in New Directions in Strategic Thinking 2.0: ANU Strategic and Defence Studies Centre’s Golden Anniversary Conference Proceedings, ed. Russell W. Glenn (Canberra, Australia: ANU Press, 2018), 91, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv47wfph.14; Michael Evans, The Tyranny of Dissonance: Australia’s Strategic Culture and Way of War, 1901–2005, Land Warfare Studies Centre Working Paper 306 (Duntroon, Australia: Land Warfare Studies Centre, 2005, 25–39; David J. Kilcullen, “Australian Statecraft: The Challenge of Aligning Policy with Strategic Culture,” Security Challenges 3, no. 4 (2007): 47–49; Tim Marshall, The Power of Geography: Ten Maps that Reveal the Future of the World (London, UK: Elliot and Thompson), xiv–xv.

2 David Horner, “Australia in 1942: A Pivotal Year,” in Australia 1942: In the Shadow War, ed. Peter J. Dean (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

3 Dibb, “The Return of Geography,” 91; Scott Morrison, “Australia and the Pacific: A New Chapter” (Speech, Townsville, Australia, November 8, 2018), https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-41938 ; Hugh White, How to Defend Australia (Carlton, Australia: La Trobe University Press, 2019), 99.

4 Marshall, The Power of Geography, 4–6.

5 White, How to Defend Australia, 33.

6 Paul Dibb, “The Importance of the Inner Arc to Australian Defence Policy and Planning,” Security Challenges 8, no. 4 (Summer 2012): 30; Department of Defence, Australian Defence (Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Printing Service, 1976), 6, https://www.defence.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-08/wpaper1976.pdf.

7 Marshall, The Power of Geography, 4–6.

8 White, How to Defend Australia, 49–50.

9 White, How to Defend Australia, 115.

10 The Canberra Times, “Leader’s Pledge to Australia,” March 27, 1942; Peter J. Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition: US and Australian Military Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, 1942–1945 (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2018), 21–28, 369–370.

11 Lida Mayo, United States Army in World War 2, The Technical Services, The Ordnance Department, On Beachhead and Battlefront (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1991), 34–41, https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/beachhd_btlefrnt/; John Robertson and John McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945: A Documentary History (St Lucia, Australia: University of Queensland Press, 1985), 277-296.

12 Charles R. Shrader, United States Army Logistics, 1775-1992: An Anthology (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1997), 43.

13 Mayo, On Beachhead and Battlefront, 39.

14 Stephen Chamberlin to Brehon Somervell, letter, February 26, 1942, record group 36, box 1, from Papers of General Stephen J. Chamberlin, MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA; Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millet, A War to be Won: Fighting the Second World War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 200.

15 Created by author using map from Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, World War II Maps, University of Texas, accessed January 25, 2024, https://maps.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/engineers_v1_1947/australia_road_net_1943.jpg

16 Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945, 139–152, 256.

17 Hugh White, ‘Strategic Interests in Australian Defence Policy: Some Historical and Methodological Reflections,’ Security Challenges 4, no. 2 (Winter 2008), 74, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26459142

18 Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945, 170–177.

19 Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition, 35; Gavin Long, The Six Years War: A Concise History of Australia in the 1939-45 War (Canberra, Australia: The Australian War Memorial and the Australian Government Publishing Service, 1973), 128–129.

20 Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945, 228.

21 Vernon Sturdee, paper by the Chief of the General Staff on Future Employment of A.I.F., February 15, 1942, in Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945, 229.

22 Horner, ‘Australia in 1942: A Pivotal Year,’ 15–17; Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945, 209–212.

23 Department of Defence, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 (Canberra, ACT: Government of Australia, 2023), 24, https://www.defence.gov.au/about/reviews-inquiries/defence-strategic-review

24 White, ‘Strategic Interests in Australian Defence Policy,’ 72.

25 Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith, Deterrence through Denial: A Strategy for an Era of Reduced Warning Time (Barton, Australia: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2021), 5, 23.

26 Dibb and Brabin-Smith, Deterrence through Denial, 6.

27 World Bank, ‘Population Density,’ accessed November 7, 2023, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.DNST?most_recent_value_desc=false

28 John L. Gallup, Jeffrey D. Sachs, and Andrew D. Mellinger, ‘Geography and Economic Development,’ International Regional Science Review 22, no. 2 (August 1999): 180–182, https://web.archive.org/web/20070609153540/http://www.earthinstitute.columbia.edu/about/director/documents/irsr0899.pdf

29 Ritij Jain, ‘How Efficient Are Economies at Using Their Land – GDP Per Unit Land Area,’ R., July 30, 2018, https://ritijjain.com/2018/07/30/gdp-per-unit-land-area.html

30 Marshall, Power of Geography, 7–9.

31 White, How to Defend Australia, 40.

32 Cairns Post, ‘Australian Population Over Seven Million,’ June 18, 1942, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/42348641

33 Robert G. Menzies, ‘1942–The Australian Economy During War,’ in Australia’s Economy in its International Context, ed. Kym Fisher (Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide Press, 2009), 505, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.20851/j.ctt1sq5w73.28

34 Kate Darian-Smith, ‘The Home Front and the American Presence in 1942,’ in Australia 1942: In the Shadow of War, ed. Peter J. Dean (Port Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 74; Long, The Six Years War, 216.

35 Long, The Six Years War, 216–217.

36 Stephen Chamberlin to Breon Somervell, letter, February 26, 1942, record group 36, box 1, from Papers of General Stephen J. Chamberlin (MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA).

37 Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition, 111–112.

38 Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition, 112, 114–117.

39 Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition, 111, 157–162, 195–196, 229, 291, 301–304.

40 Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Population Clock,’ accessed January 24, 2024, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/population-clock-pyramid

41 Statista, ‘Estimated Pre-Second World War Populations of Selected Allied and Axis Countries and their Territories in 1938,’ accessed November 13, 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1333819/pre-wwii-populations/; World Bank, ‘Population, Total,’ accessed November 13, 2023, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL

42 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Demographic Profile,’ accessed January 23, 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australians/contents/demographic-profile; Australian Bureau of Statistics, Census 1938 (Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Printing Service, 1938), 341, https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/free.nsf/0/67D0590CE4E9A7DACA257AF30010D8C2/$File/13010_1938%20section%2013.pdf

43 Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Labour Force,’ accessed January 23, 2023, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia/latest-release; Menzies, ‘1942–The Australian Economy During War,’ 518.

44 David Brewster, ‘Building Australia’s Unified Regional Strategy Through the Indo-Pacific Concept,’ in Indo-Pacific Strategies: Navigating Geopolitics at the Dawn of a New Age, eds. Brendon J. Cannon and Kei Hakata (Abingdon, United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis, 2021), 51; Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review 2023, 75.

45 White, How to Defend Australia, 119.

46 Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review 2023, 75; White, How to Defend Australia, 116.

47 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Census of the Commonwealth of Australia (Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth Government Printer, 1933), 329, https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/free.nsf/0/67D0590CE4E9A7DACA257AF30010D8C2/$File/13010_1938%20section%2013.pdf

48 Department of Post-War Construction, ‘Development of Australia,’ Map G8961.G2 194, National Archives of Australia Trove, accessed January 25, 2024, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-234332601/view

49 ABS, Census of the Commonwealth of Australia, 329.

50 Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945, 260.

51 Long, The Six Years War, 171–172.

52 Long, The Six Years War, 173; Iven Mackay to Francis Forde, memorandum, ‘Defence of Australia,’ February 4, 1942, in Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945, 260–261.

53 Mackay, ‘Defence of Australia,’ 262.

54 Long, The Six Years War, 174.

55 Anthony Arnold, ‘A Slim Barrier: The Defence of Mainland Australia 1939-1945’ (PhD diss., University of New South Wales, 2013), 166, http://hdl.handle.net/1959.4/53041233; Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition, 145.

56 David Larr, Petersburg Plan: Redistribution of Allied Forces SWPA in Event of Japanese Success in the Solomon Islands, October 31, 1942, records from General Headquarters Southwest Pacific Area (United States Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA).

57 Larr, Petersburg Plan.

58 David Larr to Stephen Chamberlin, original secret memo, Petersburg Plan, October 31, 1942, historical records index card H223, records from General Headquarters Southwest Pacific Area (MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA).

59 Arnold, ‘A Slim Barrier,’ 234.

60 Created by author using map from ABS, Census of the Commonwealth of Australia, 329.

61 White, How to Defend Australia, 116.

62 Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review 2023, 75.

63 Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review 2023, 7, 19, 58, 60, 65, 75–76.

64 Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Regional Population–Interactive Maps,’ accessed January 11, 2024, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/latest-release.

65 Albert Palazzo, Resetting the Australian Army, Australian Army Occasional Paper No. 16 (Canberra, Australia: Australian Army Research Centre, 2023), 4; White, How to Defend Australia, 116.

66 White, How to Defend Australia, 116–119.

67 Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review 2023, 58–63.

68 Kilcullen, ‘Australian Statecraft,’ 50; Michael O’Connor, ‘Trade and National Security,’ Australian Army Journal 2, no. 1 (2004): 21–26; White, How to Defend Australia, 130.

69 O’Connor, ‘Trade and National Security,’ 23.

70 Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review 2023, 25.

71 Joanne Wallis, ‘The Pacific Islands: an “Arc of Opportunity”,’ Submission 2, Inquiry into Australia’s Defence Relationships with Pacific Island Nations, Canberra, Australia, 2020, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/PacificIslandnations/Submissions; White, How to Defend Australia, 110–115

72 James P. Belshaw, ‘Markets for Australian Exports,’ Far Eastern Survey 14, no. 5 (1945): 58.

73 Belshaw, ‘Markets for Australian Exports,’ 58.

74 Long, The Six Years War, 220; Menzies, ‘1942–The Australian Economy During War,’ 506.

75 Long, The Six Years War, 220–222; Menzies, ‘1942–The Australian Economy During War,’ 507.

76 Long, The Six Years War, 474–475.

77 Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (New York, NY: Random House, 1990), 18–24; Long, The Six Years War, 193; John Prados, Islands of Destiny: The Solomons Campaign and the Eclipse of the Rising Sun (New York, NY: NAL Caliber, 2013), 5.

78 Prados, Islands of Destiny, 43–44; Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition, 102.

79 Mayo, On Beachhead and Battlefront, 44–61.

80 Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review 2023, 37; O’Connor, ‘Trade and National Security,’ 22.

81 Reserve Bank of Australia, ‘Snapshot Comparisons September 2022–September 2023,’ accessed January 19, 2024, https://www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/digital-interactives/snapshot-comparison/.

82 Australian Naval Institute and the University of New South Wales, Protecting Australian Maritime Trade 2022 (Report, Australian Naval Institute and the University of New South Wales Australia, Canberra, Australia, 2022), 6, https://navalinstitute.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Protecting-Australian-Maritime-Trade-Report-2022-Final-version.pdf; Reserve Bank of Australia, ‘Snapshot Comparisons September 2022–September 2023.’

83 Brewster, ‘Building Australia’s Unified Regional Strategy,’ 52–55.

84 Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review 2023, 45.

85 Kilcullen, ‘Australian Statecraft,’ 52.

86 John Curtin, ‘The Task Ahead,’ The Herald, December 27, 1941, https://john.curtin.edu.au/pmportal/text/00468.html

87 Adam Triggs and Peter Drysdale, ‘Complex Trade-offs: Economic Openness and Security in Australia,’ in Navigating Prosperity and Security in East Asia, ed. Shiro Armstrong, Tom Westland, and Adam Triggs (Canberra, Australia: ANU Press, 2023), 59; US Department of State, ‘U.S. Relations with Australia,’ accessed January 21, 2024, https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-australia/

88 Brewster, ‘Building Australia’s Unified Regional Strategy,’ 43–46; White, ‘Strategic Interests in Australian Defence Policy,’ 68.

89 Kilcullen, ‘Australian Statecraft,’ 54.

90 British War Cabinet, Points on the Discussion Regarding Fall of Singapore, February 16, 1942, in Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945, 211.

91 Arnold, ‘A Slim Barrier,’ 166; Winston Churchill to John Curtin, Cablegram 342, February 22, 1942, in Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945, 237; John Curtin to Winston Churchill, Cablegram 139, February 23, 1942, in Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945, 238.

92 Honae Cuffe, The Genesis of a Policy: Defining and Defending Australia’s National Interest in the Asia-Pacific, 1921–57 (Canberra, Australia: ANU Press, 2021), 111–112; Horner, ‘Australia in 1942: A Pivotal Year,’ 27; Ross McMullin, ‘Dangers and Problems Unprecedented and Unpredictable: The Curtin Government’s Response to the Threat,’ in Australia 1942: In the Shadow of War, ed. Peter J. Dean (Port Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 93–95; Albert Palazzo, ‘The Overlooked Mission: Australia and Home Defence,’ in Australia 1942: In the Shadow of War, ed. Peter J. Dean (Port Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 62.

93 Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition, 369; Long, The Six Years War, 177–178; Maurice Matloff and Edwin Marion Snell, Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare, 1941-1942, no. 1 (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1953), 131.

94 Long, The Six Years War, 181.

95 John Curtin to Douglas MacArthur, ‘The Directive of the Commander-in-Chief,’ April 15, 1942, in Robertson and McCarthy, Australian War Strategy 1939-1945,299.

96 Horner, ‘Australia in 1942: A Pivotal Year,’ 25.

97 Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millet, A War to be Won: Fighting the Second World War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 199.

98 Mayo, On Beachhead and Battlefront, 44–85; Prados, Islands of Destiny, 238–240.

99 Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition, 195–196, 200; Murray and Millett, A War to be Won, 206–207.

100 Cuffe, The Genesis of a Policy, 109–123; Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition, 137; Peter Edwards, Permanent Friends? Historical Reflections on the Australian-American Alliance (Double Bay, Australia: Lowy Institute for International Policy, 2005), 9–14, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/58867/2005-12-13.pdf

101 Edwards, Permanent Friends? Historical Reflections, 11.

102 Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review 2023, 18.

103 Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review 2023, 17, 37.

104 Stephan Frühling, ‘Is ANZUS Really an Alliance? Aligning the US and Australia,’ Survival 60, no. 5 (2018): 199–218; Triggs and Drysdale, ‘Complex Trade-offs,’ 58.

105 White, ‘Strategic Interests in Australian Defence Policy,’ 78.

Defence Mastery

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.