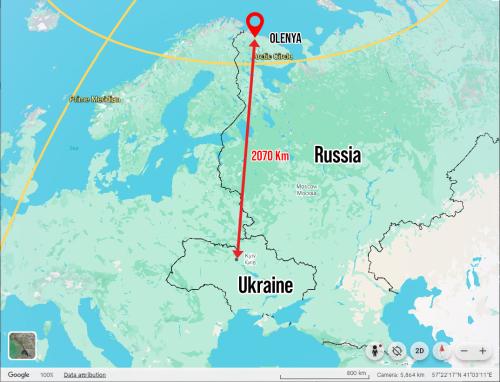

On June 1, Ukraine struck four Russian aviation mainstays, those being Olenya, Ivanovo, Dyangilevo, and Belaya, in a coordinated drone strike.[1] Codenamed Operation Spider Web, the ‘Call of Duty’-styled operation inflicted a crushing blow to Russia’s long-range bomber fleet, including Tu-95MSs and Tu-22M3s, along with A-50 AWACS. These aircraft were used to conduct long-range strikes on Ukraine and were responsible for the bastion defence and second-strike capability. Due to the operation’s vast geographical expanse, the precisely planned strike challenges the long-held notion of Russia’s geographical insulation, particularly in remote sanctuaries like the Arctic region, once thought of as geographically impregnable and far from Ukraine’s long-range capabilities.

Eighteen months before the attack, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) covertly smuggled 150 small drones, 300 explosive payloads, and modular launch systems compartmentalised inside modified cargo trucks. What made the raid unique from legacy operations such as Operation Jaywick and Operation Source was its stealth execution through Russian territory, involving civilian participation. The drones were then transported to various locations near the Russian airbases.[2] On arrival, they were released from the compartments and directed toward their target destinations. To facilitate seamless navigation, drones utilised an open-source software called ArduPilot, enabling them to autonomously follow their destined path.[3] As evident in the footage, the drones emerge from containers, follow a stable flight path, and subsequently lowering themselves to strike the vulnerable areas of the bombers, particularly around the wings and fuselages.[4]

The attack has notable impact for Russia’s military and economic posture in the Arctic region. Regarded as a Cold War missile pathway and a nest for its second-strike capability, the Arctic retains the status of high priority in Russian military calculus.[5] To ensure its perimeter defence, Russia follows the ‘bastion defence’ strategy by concentrating offensive and defensive assets within its Northern military district.[6] The vast geographical depth of the region further reinforces this approach, offering a natural buffer against potential foreign incursions. Olenya airbase constitutes a significant component of the perimeter defence of Russia’s second-strike capability. Being a home to the 40th Composite Aviation Regiment, it houses a significant number of Tu-95MS and Tu-22M3 bombers, capable of conducting long-range strikes around the Arctic and Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) gap.

The Greenland Iceland United Kingdom (GUIK) Gap. Google, Google Maps, and Google Earth are trademarks of Google LLC. This article is not endorsed by or affiliated with Google.

Likewise, the geo-economic significance of the region, estimated globally to contain 30% of the world’s undiscovered natural gas and 13% of its oil, makes the secluded geography an integral part of Russia’s geo-strategic agenda.[7] As outlined in its Arctic strategy 2020-2035, Russia aims to develop the untapped potential of hydrocarbons through the Yamal LNG and Arctic LNG-2 projects. The strategy also pivots on transforming the Northern Sea Route (NSR) into a global shipping artery, elevating the Arctic status as a ‘strategic resource base’.[8] Therefore, the stationing of the offensive and defensive assets in the Arctic tundra not only demonstrates the power projection in the High North, but also to consolidate Russia’s hold on the energy riches lying underneath the thick permafrost.

Russia’s geopolitical thinking in the Arctic tends to avoid foreign military domination, securing the energy infrastructure and strategic nuclear forces stationed at the Kola Peninsula.[9] Traditionally, the Russian military has remained infatuated with legacy battle systems. The development of long-range bombers, intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), nuclear-powered submarines, and even the exotic doomsday torpedoes[10], reflects its intent to preserve its stretched geography. Being caught in the fear of encirclement and foreign invasion, these weapons are viewed as key in protecting Russia’s vast geographical envelope and to avoid a strategic surprise at all costs.

However, this strategic disposition is challenged by the rise of drone warfare. Despite a robust Anti-access/Area-denial (A2/AD) environment around the Arctic bases, the successful execution of Operation Spider Web provides a glimpse into future warfare where cheap and hi-tech solutions can target anything, anytime and anywhere. It also reflects meticulous fusion of Ukrainian military strike capabilities and intelligence to facilitate seamless integration in executing the operation deep into Russia’s strongholds. Moreover, the operation’s success across a vast geographical magnitude unmasks vulnerabilities in Russia’s rear defences. The targeted bombers, notably Tu-95s and Tu-22s, constitute a critical leg of Russia’s nuclear triad that are no longer in production and have no instant replacement. This would be comparable to the US losing a bunch of B-52 and B-2 bombers in a similar assault.

Operation Spider Web stands as a stark testament to how modern drone warfare is eroding Russia’s age-old reliance on strategic depth and harsh geography for security. Once shielded by vast tundras and frigid expanses, the Arctic bastion has proven vulnerable to small, cheap, and highly adaptable unmanned systems that slip through radar gaps and strike at the very core of Russia’s second-strike capabilities.

In this new era, the belief that distance and climate alone can protect critical assets is being shattered by the precision and reach of drones. Just as the Mongol horsemen once blitzed the steppes, Ukraine’s drones now pierce the Arctic veil, exposing the fragile underbelly of Russia’s long-held defence doctrines. The question now is not if, but how quickly, Russia can adapt to defend a geography that no longer guarantees safety from eyes and explosives in the sky.

Russia’s traditional confidence in its vast strategic depth has been shaken by Ukraine’s ability to launch asymmetric attacks deep inside its borders, despite its sheer size and remoteness. For Australia, long reliant on its geographic isolation as a natural shield, this should raise serious questions. What lessons should we draw about our own vulnerability and how we think about distance-as-defence?

We want to hear your thoughts—share your perspective on whether Australia’s ‘tyranny of distance’ is still an asset, or a dangerous illusion in an age of long-range and unconventional threats. Add your voice in the comments below!

1 Laura Gozzi and BBC Verify, “How Ukraine carried out daring ‘Spider Web’ attack on Russian bombers,” BBC, June 2, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cq69qnvj6nlo

2 Katreyna Bondar, “How Ukraine’s “Operation Spider Web” Redefines Asymmetric Warfare,” CSIS, June 2, 2025,https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-ukraines-spider-web-operation-redefines-asymmetric-warfare

3 Katja Bego “Ukraine’s Operation Spider’s Web is a game-changer for modern drone warfare. NATO should pay attention,” Chatham House, June 6, 2025, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2025/06/ukraines-operation-spiders-web-game-changer-modern-drone-warfare-nato-should-pay-attention

4 The Kyiv Independent, “New footage from Ukraine’s Operation Spiderweb hitting Russian bombers,” Youtube video, June 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8JjC_119WUA

5 Shaheer Ahmad and Mohammad Ali Zafar, “Russia’s Reimagined Arctic in the Age of Geopolitical Competition,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, (March 2022): 1-24, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Mar/08/2002952492/-1/-1/1/JIPA%20-%20AHMAD%20&%20ZAFAR%20-%20MAR%2022.PDF

6 Mathieu Boulegue, “Russia’s Military Posture in the Arctic: Managing Hard Power in a ‘Low Tension’ Environment,” Chatham House, October 15, 2024, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2019/06/russias-military-posture-arctic/2-perimeter-control-around-bastion

7 U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Arctic oil and natural gas resources,” January 20, 2012, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=4650

8 President of Russia, “Changes to Basic Principles of State Policy in the Arctic until 2035,” February 21, 2023, http://en.kremlin.ru/acts/news/70570

9 Michael B. Petersen and Rebecca Pincus, “Arctic Militarization and Russian Military Theory,” Orbis 65, no. 3 (2021): 490-512, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2021.06.011

10 Silky Kaur, “One nuclear-armed Poseidon torpedo could decimate a coastal city. Russia wants 30 of them,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, June 14, 2023, https://thebulletin.org/2023/06/one-nuclear-armed-poseidon-torpedo-could-decimate-a-coastal-city-russia-wants-30-of-them/

Defence Mastery

Ukraine's Drones Pierce Russia’s Arctic Bastion © 2025 by . This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.