Introduction

In an era marked by rapid technological advancements and evolving military threats, Australia's defence strategy has increasingly focused on the adoption of new long-range capabilities to safeguard its sovereignty. One critical aspect of this approach is the implementation of a deterrence-by-denial strategy designed to prevent adversaries from projecting power upon Australian territory. Australia has invested heavily in nuclear-powered submarines as the cornerstone capability of the deterrence strategy, but new submarines will not be delivered until the 2030s. Australia is also seeking to enhance deterrence during a period where the Australian Defence Force (ADF) is struggling to meet recruitment targets and is objectively shrinking in terms of manpower.[1] The adoption of uncrewed systems provides an opportunity to promptly increase the lethality and range of Australia’s air domain force projection capability. Moreover, within the air domain, the Defence Strategic Revie (DSR) identified that aircrew shortages for air combat capabilities are insufficient to operate at high tempo, so the adoption of uncrewed systems can mitigate this shortfall and achieve more with the limited aircrew cohort.[2]

Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA), autonomous systems capable of enhancing the operational range and lethality of the ADF, have matured to become a viable force structure option. This essay answers the question of how Australia can best use CCAs to execute its strategy of denial. By adopting CCAs tailored towards countering the launch platforms for air-launched cruise missiles and surface-launched land-attack cruise missiles, Australia can generate affordable mass capable of ‘impactful projection’ with a sovereign production capacity to replace aircraft lost to attrition. These systems offer a cost-effective solution to countering modern threats, particularly as Australia's strategic environment becomes increasingly contested with the rise of China.

This essay argues that cruise missile attacks on northern Australia constitute a credible threat that can be countered by using CCAs to hold the cruise missile launch platforms at risk. Given that cruise missiles can be most readily launched from long-range bombers or surface action groups, the essay will then argue how the attributes of CCAs can best be used to counter these threats. Finally, the essay will argue that for the deterrent effect of CCAs to be credible and provide a means of asymmetric cost exchange, Australia must possess a sovereign CCA design, development and manufacturing capability for the types of CCAs most likely to be subject to attrition in a defensive scenario.

Strategy of denial

Australia has adopted a national defence strategy of deterrence by denial, which requires the pursuit of capabilities that improve the range and lethality of the ADF. These capabilities are critical to the ADF’s ability to credibly hold adversary forces at risk if they seek to project military power against Australian territory and the northern approaches. The National Defence Strategy 2024 (NDS) states that Australia requires an enhanced ‘capacity to deter coercion and to increase the ADF’s capacity for impactful projection’.[3] Impactful projection demands the imposition of costs upon an adversary, at long ranges, to deter aggressive action against Australia.[4] The ADF Theatre Concept, Concept ASPIRE, details how Australia will seek to impose unacceptable costs on an adversary. The concept concedes that an adversary may decide to attack Australia if the cost is low and is outweighed by the benefits. To deter attacks, Concept ASPIRE outlines various ways to impose costs upon an adversary. Cost imposition can be as direct as destroying adversary forces or may include broader costs such as ‘delay, reputational damage, economic penalty or military advantage’.[5] CCAs provide a unique set of attributes from a force design and operational perspective that can enhance Australia’s ability to set the cost exchange ratio in their favour. Specifically, CCAs should contribute to the defence of Australia and the northern approaches with capabilities that impose costs at long ranges.

What is a collaborative combat aircraft?

A CCA is a specific type of autonomous collaborative platform (ACP) that incorporates high levels of autonomy to enable human-machine teaming with crewed aircraft to execute air combat missions. ACPs are, in turn, Uncrewed Air Systems (UAS) that are comprised of uncrewed air vehicles (UAV), ground control stations (GCS) and, in some cases, a command and control system or segment. Given the focus on air combat roles, CCAs are, therefore, part of two overlapping subtypes of UAS: ACPs and uncrewed combat air systems (UCAS). ACPs incorporate high levels of autonomy to conduct airborne missions such as aerial refuelling, ISR or transport and CCAs are the specific type of ACP that conduct air combat missions.[6] The United States Air Force (USAF) differentiates ACPs from current-generation UAVs in that ACPs are intended for use ‘in conjunction with other combat aircraft to perform a wide range of missions in contested operational environments’.[7] However, CCAs also conform to the definition of uncrewed combat air vehicles (UCAV), defined as ‘an unmanned military aircraft of any size which carries and launches a weapon, or which can use on-board technology to direct such a weapon to a target’.[8] So, it follows that CCAs are UCAVs, designed to incorporate high levels of autonomy to carry and launch or support the launch of weapons to execute air combat missions.

Why USE CCAs to counter the cruise missile threat?

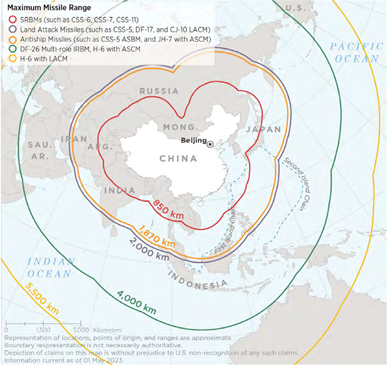

The ADF requires credible defences to avoid being subject to military coercion or attack. China has multiple long-range strike systems capable of engaging targets within the Australian mainland. Historically, Australia’s geography has provided significant advantages in terms of isolation and a large moat or ‘air-sea gap’ that has been central in strategies to defend continental Australia. However, the air-sea gap is no longer enough to ensure the Australian continent remains free from attacks as regional capabilities advance further into the missile age. In support of this assessment, Hellyer argues that fighter aircraft with a 1000 km combat radius may have been sufficient to defend the ‘air-sea gap’ in the 1980s but Australia’s potential adversary now has capabilities that can strike from 3000 km away.[9] More concerningly, the United States (US) Defence Intelligence Agency assesses that China possesses systems capable of attacking 5500 km from their mainland which encapsulates a large portion of northern Australia, as depicted in Figure 1.[10] As China has pursued military parity with the US, the PLA has built a force that includes a low-cost missile force comprised of ballistic and cruise missiles, ‘explicitly designed to keep the US and allied forces at arm’s reach’.[11] Further, China has closely studied US force structure and operational posture and developed plans to counter the US and its allies across the Indo-Pacific. This could see China seeking to degrade US and allied sortie generation by striking theatre airbases and ground support capabilities such as those hosting US bomber forces in northern Australia.[12]

Of the missiles that threaten Australia, defence against ballistic missiles requires attributes not readily incorporated by CCAs with dedicated integrated air and missile defence systems best suited to this task. Ballistic missile flight is doctrinally divided into three phases: boost, midcourse and terminal.[13] Ballistic missile defence systems are designed to counter ballistic missiles in each phase of flight. The boost phase occurs from the point of launch until booster burnout and defence in this stage requires assets to be near the launch site. For missiles launched from mainland China and capable of striking Australia, the boost phase would occur at least 4000 km away. While boost phase counters are being developed for launch from F-35, a boost phase counter would require penetration of China’s formidable anti-access area denial system.[14] Such penetration is not viable for Australia, given the forward posture necessary to engage a missile in the boost phase. The midcourse phase occurs beyond the earth’s atmosphere and is, therefore, beyond the physical capabilities of air-breathing systems such as CCAs. Midcourse defence is typically a task for rocket-powered interceptors such as the SM-3 missile.[15] Finally, the terminal phase commences when the ballistic missile re-enters the atmosphere, which results in a narrow window of opportunity to counter the missile. Terminal phase defence systems are typically exquisitely expensive because of the advanced technologies and precision required to intercept and destroy a small and high-speed target. While Australia does possess limited terminal phase capability with the Air Warfare Destroyer and intercept missiles such as SM-2 and SM-6, further analysis of ballistic missile defence is beyond the scope of this paper.[16] Given the challenges ballistic missile defence poses to airbreathing aircraft such as CCAs, this leaves cruise missiles as the potent and long-range threat that CCA employment can be focussed on.

CCAs provide a means to extend the range and lethality of Australia’s air combat capability to interdict long-range bombers before missile launch. China’s land attack cruise missiles lack the range to attack Australia from Chinese territory and require forward projection by long-range bombers. From the air, China possesses a large fleet of H-6K bombers that are capable of carrying six land attack cruise missiles, which creates a system capable of attacking airfields in the second island chain from mainland China which includes large parts of Australia, as depicted in Figure 1.[17] According to Janes, the H-6 has been displayed armed with two CJ-10K/KD-20 and two KD-63 cruise missiles with the CJ-10K having a reported range of 1,500+ km.[18] Interdicting an H-6 before a missile launch would require a counter-air package to fly more than 1500 km, which exceeds the unrefuelled combat radius of Australia’s crewed fighters.[19] Given the criticality and limited size of Australia’s air-to-air refuelling capability, CCAs could satisfy this range requirement without placing additional burden on the air-to-air refuelling capability. Supporting the notion that CCAs could be used to establish a potent counter-air capability, the Mitchell Institute CCA wargame concluded that CCAs could complement and enhance crewed fighters in the counter-air role, which could include interdiction of H-6 strike packages.[20]

CCAs can embody the range, lethality and survivability to hold adversary surface action groups (SAG) at risk. The US Department of Defense anticipates, ‘in the near-term, the PLAN will have the ability to conduct long-range precision strikes against land targets from its submarine and surface combatants using land-attack cruise missiles, notably enhancing the PRC’s power projection capability’.[21] From the sea, China possesses anti-ship cruise missiles that include land-attack variants. Notably, the YJ-18 series of cruise missiles have been integrated for use on the Renhai-class cruiser and Luyang-III class destroyer with an estimated range of 220-540 km.[22] The Mitchell Institute assess that Chinese SAGs will mitigate their physics-limited radar horizon by integrating KJ-500 Airborne Warning and Control aircraft to detect threats to the SAG. This increased radar coverage would support the use of their HHQ-9 surface-to-air missile out to the maximum range of 250 km, thus complicating attempts to directly engage the SAG as it is effectively a floating integrated air defence system.[23] Successfully striking such a well-defended SAG would require the use of attacking aircraft with sufficient survivability to penetrate the HHQ-9 missile engagement zone or the use of exquisite standoff weapons.

CCAs provide a means to complement Australia’s crewed fighters to effectively counter China’s potent cruise missile capabilities. Whether from the air or the sea, China possesses credible systems capable of projecting force upon Australia. However, autonomous and attritable systems like CCAs could form the basis of an operational approach to counter these threats. The counter should focus towards attacking the launch platforms, denying missile launches to efficiently and effectively defend against cruise missiles, i.e. attacking the archer and not the arrow. Long-range CCAs with sensing and offensive weapons could be used to hold Chinese bombers and surface ships at risk, denying them options to conduct long-range strikes on Australia. The Mitchell Institute has conducted several studies and wargames investigating the roles and types of CCAs that would be of greatest utility in countering China’s forces. In the 2022 study on penetrating strike capabilities, one of the priority vignettes was a maritime strike against a Chinese surface action group, concluding that CCAs have great potential in this role.[24] These studies and wargames demonstrate that CCAs significantly enhance the survivability and lethality of crewed fighters and will be central to countering China’s offensive capabilities.

HOW CAN Collaborative combat aircraft Best Counter the cruise missile threat?

Australia can counter the cruise missile threat by exploiting the unique attributes of CCAs to establish a long-range deterrent that can hold adversary launch platforms at risk. The primary difference between a crewed aircraft and a CCA is the removal of the human pilot from the aircraft and replacement with an advanced autonomy system, thus providing design and operational employment opportunities not available with crewed aircraft. Removing the pilot allows the platform to be intentionally lost to attrition or even operated as an expendable asset for high-risk missions. Adopting CCAs can also alleviate the ethical concerns associated with sending humans into highly contested environments. Removing humans then allows CCAs to be designed for shorter service life than crewed platforms, which can bring efficiencies and cost reductions, both in design and operations. Further, not having a pilot onboard also means the weight associated with cockpits and other human life-support systems can be used to enhance aspects of the design that contribute to mission effectiveness, such as increased range or payload capacity. Lastly, the removal of human crew allows retention of higher risk during development and flight test phases that can result in reduced program costs and increased speed of introduction to service.

Affordable attrition

Australia should adopt CCAs capable of penetrating the missile engagement zones of adversary surface action groups and bomber strike packages to hold them at risk. CCAs can be designed to have ‘enough range and survivability to ensure they will reach their weapon launch points’.[25] The RAF has characterised the spectrum of survivability for CCAs by breaking it into three tiers. Tier one platforms are expendable with a life-cycle of one or very few missions, tier two platforms are attritable, expected to survive the mission, but losses are acceptable, and tier 3 are survivable where the platforms are of high strategic value, and the loss would impact combat effectiveness.[26] By designing CCAs to be attritable systems, they can deliver less sophisticated weapons closer to a target or mitigate situations where the adversary possesses a missile range overmatch, which affords them a tactical sanctuary with a first shot advantage. The US Air Force has closely studied these trade-offs in survivability, weapon cost and sophistication when comparing penetrating systems versus standoff systems. Their studies concluded that sufficiently survivable penetrating systems are more cost-effective in long conflicts as the cost of exquisite weapons can quickly outweigh platform costs.[27] By adopting a CCA that is sufficiently survivable to penetrate adversary defences at a cost point considered attritable, Australia can affordably increase the strategic depth of the air combat capability and enhance the deterrence effect it provides.

Australia should embrace CCAs that can be affordably designed to optimise their characteristics for denying cruise missile launch platforms. Aircraft can be designed with high levels of survivability against specified threats, with the survivability coming from a variety of technologies, including low observability and self-protection measures such as flares, decoys and electronic attack systems. The team of experts assembled for the Mitchell Institutes 2024 CCA wargame advocated for the development of a CCA fleet that balances unit cost against attributes such as ‘size, low observability, range, [and] mission systems.[28] Survivability can be a significant cost driver for aircraft but is required to mitigate the risk to human life for crewed platforms and the risk to platform loss. However, CCAs present options to deliberately design systems with just enough survivability to complete the mission, which can be accompanied by a willingness to accept attrition of the platform as the price of mission success. Conversely, the ever-present temptation to increase the capability by adding design features above the minimum required to complete the mission must be resisted to ensure the cost advantage of CCAs is not diminished. Exploiting these design dimensions presents Australia with ways to utilise CCAs to hold adversary long-range strike systems at risk.

Adopting CCAs allows operational commanders to decouple the risk to force and the risk to the mission, which can reduce barriers to counter-attacking highly defended targets, thus increasing the credibility of deterrence. Traditionally, operational employment of crewed aircraft in contested environments presented commanders with a high risk to force, i.e. loss of human life and high risk to mission, i.e. mission failure due to not delivering weapons and achieving the intended military effect.[29] By removing humans from the aircraft, these two risks can be considered separately, which opens up new opportunities, but it also presents potentially new ethical dilemmas. If the risk to human life can be affordably reduced through the use of CCAs for high-risk missions, then the dilemma arises as to whether it remains ethical to expose humans to this risk if there are alternate options.[30] Given the societal aversion to combat casualties in Western nations, an adversary could seek to exploit this to coerce through the threat of force. By designing CCAs to be attritable, commanders can accept high risk to the mission while mitigating risk to force, which in turn increases the credibility of the deterrence effect Australia’s military is intended to create.

Exploiting CCA attributes to bolster deterrence

Australia can adopt CCAs to complement the existing crewed fighter capability and enhance the overall resilience of the air combat capability, but it will require new approaches. CCAs afford new opportunities by creatively exploiting their unique system attributes. However, this will require a departure from traditional crewed aircraft thinking and processes. The Mitchell Institute identified that exploiting these opportunities will require the adopting Air Force to ‘aggressively pursue novel, and in some cases, untested approaches to UAV engineering, production, operations, and sustainment’.[31] As an example, while CCAs can be designed to conduct specific air combat missions, an overarching aspect of the US Air Force approach is to distribute mission functions across a family of systems to ‘amplify combat effectiveness’.[32] Distributing capabilities across CCAs rather than concentrating them on a small number of exquisite platforms increases the resilience of the force and presents the adversary with a far more complex defensive dilemma.[33] This approach allows for designs to be optimised, which can enhance performance while reducing costs associated with ‘jack-of-all-trade’ aircraft like the F-35, which Allen et al. argue is costly, complicated and unwieldy.[34]

The opportunity to adopt novel approaches to technical airworthiness risk must be exploited to field CCAs in a strategically relevant time frame to mitigate a shortfall in deterrence credibility until nuclear-powered submarines arrive. The removal of humans affords opportunities for new approaches to technical risk, which can reduce development times and enhance capability outcomes. A prime example is partitioning air vehicle control software from mission autonomy software to avoid costly regression testing during upgrades. Air vehicle control software will still be subject to military airworthiness certification to achieve an agreed level of safety, which is time consuming and resource-intensive, as are changes to systems with an extant certification. To exploit the potential of CCA mission autonomy and expedite software development, an alternate approach must be taken to enable rapid software development and fielding that is not subjected to conventional airworthiness processes.[35] The USAF appears to be harnessing this opportunity by running separate air vehicle and autonomy software competitions for the first tranche of CCA.[36] Australia should take this approach to CCA development and adopt US autonomy software architecture as an example of the technical integration sought by Concept APEX.[37] This would allow US-developed autonomy software to be incorporated into Australian-designed and manufactured air vehicles, thus assuring sovereign air vehicle supply while benefiting from US software development expertise, interoperability and economy of scale.

Fully exploiting the capability advantage of CCAs requires the ability to rapidly field enhancements in technology, which requires revised approaches to flight testing. Testing consumes significant time during the aircraft development phase, and the use of traditional crewed aircraft approaches will hinder the ability to rapidly deploy CCAs in operationally relevant time frames.[38] Accepting higher risks during flight testing to accelerate the development and introduction to service is critical, given the reduction in strategic warning time. This is particularly relevant for testing mission autonomy software. Instead of applying crewed aircraft standards, the approach that separates air vehicle control from mission autonomy should be used.

Logistics and basing considerations for enhanced deterrence

CCAs would have a stronger deterrent effect if positioned at various locations across northern Australia to defend against cruise missile launch platforms more effectively. Two important considerations for Australia’s adoption of CCAs are basing and force protection. Given the advantages of CCAs in combat, it is reasonable to expect they would be targeted in enemy attacks. Mitchell Institute wargames identified that protecting CCAs from attack and providing adequate supply across dispersed operating locations to maintain sortie generation are unsolved concerns.[39] These issues should be prioritised for analysis and assessment as Australia develops and refines CCA operating concepts. Distributing CCAs across a network of bases, such as Australia’s northern bases, could complicate the adversary's ability to ‘find, fix, and attack’ the capability on the ground where they are most vulnerable.[40] This dispersal could raise the costs of an adversary attack, thus contributing to the deterrent effect.

Australia can best use CCAs to enhance the range of lethal force projection without placing additional demand on already over-subscribed air-to-air refuelling capacity. Australia has a relatively small fleet of air-to-air refuelling aircraft, and the recent Integrated Investment Program did not allocate funds to procuring additional tankers.[41] Given the existing criticality of tankers for the operation of crewed aircraft, CCAs must possess sufficient unrefuelled combat radius to hold cruise missile launch platforms at risk beyond their missile launch point. Fielding CCAs, which require air-to-air refuelling to deliver operationally meaningful force projection from Australian bases, would degrade rather than enhance air combat capability. The weight reduction afforded by removing cockpits and associated systems from CCA designs should be prioritised towards increasing range and combat radius so they can mitigate the range limitations of Australia’s crewed fighters and the dependency on air-to-air refuelling.

Sovereign capability enhances deterrence credibility

A sovereign capability to manufacture CCAs enhances self-sufficiency and reduces the risk of being unable to replenish aircraft from allies during conflicts. Developing attritable capabilities requires consideration of the underpinning logistics approach to ensure an appropriate cost-to-risk ratio for their use and a means of replenishing operational units when aircraft are damaged. The UK Ministry of Defence acknowledges this consideration in their Autonomous Collaborative Platform Strategy, accepting that aircraft may be lost when operated in hostile environments. The UK strategy states CCAs ‘should be acquired with an expectation that stocks may need to be rapidly replenished and capabilities re-evaluated once use begins’.[42] This need can be met by slowly manufacturing CCAs during peacetime and stockpiling them for use, as is currently done with Australia’s guided weapons or alternately having access to a manufacturing capability (sovereign or allied) with scalable capacity to replace damaged aircraft during conflict. However, it must be noted that any conflict in which Australia commits CCAs to missions with a high risk of attrition is likely to also involve the US. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that US production capacity will be prioritised towards meeting US needs, as was Australia’s experience in WWII. The USAF is preparing for a conflict that is likely to see high levels of attrition, not seen since WWII, and their senior leaders acknowledge that developing the industrial capacity to meet that demand will be challenging, given contemporary budget pressures.[43] Therefore, Australia must be self-sufficient in terms of replenishing CCAs lost to attrition, which requires a sovereign manufacturing capability.

Australia must establish a viable means of replenishing damaged CCAs to ensure the deterrence effect they generate is credible. The RAF recognise that CCAs ‘must be affordable and of regenerative mass to present a credible force capable of continued operations despite attrition’.[44] While stockpiling is a viable source of replenishment, it has two key drawbacks, the first is that a stockpile is finite and expensive to establish, and a determined adversary could simply seek to exhaust a nation’s stockpile in a war of economic attrition. Secondly, stockpiling implies that aircraft would require a fixed hardware configuration that would lose its competitive advantage over time and inhibit exploitation of advances in manufacturing, computing and sensing technologies. The alternative to stockpiling is to invest in scalable manufacturing capacity that operates at a minimum viable level during peacetime with provisions to dramatically expand manufacturing in conflict.[45] A scalable CCA production capability with the capacity to surge in wartime to support tolerance for operational attrition that allows the full exploitation of attritional or expendable systems.[46] However, the operational attrition of CCAs must be balanced against the capacity to replenish operational units as high attrition may be viable in a short conflict but become intolerably expensive in a long conflict.[47] Investing in a scalable CCA manufacturing capability is the most suitable means of ensuring the risk of platform attrition is operationally tolerable.

Affordable mass and cost asymmetry

CCAs provide Australia with a means of obtaining affordable mass to create asymmetric cost imposition that is not viable using crewed platforms. CCAs provide the opportunity to establish asymmetric cost imposition on an adversary, raising the costs above the benefits of aggression. At a time when a large portion of the Australian Defence Force capability budget has been assigned to maritime capabilities, most notably the nuclear-powered submarine program under AUKUS pillar one, CCAs provide an opportunity for Australia to substantially increase the lethality of the air combat program. Given the expense of crewed aircraft and challenges associated with recruiting, training and retaining aircrew, CCAs ‘could help offset serious force structure shortfalls’.[48] For Australia to successfully deter a much more powerful adversary, credible and affordable capabilities are required to shift the ‘cost exchange ratio’ in favour of Australia.[49] USAF Lt General Steven Kwast summed up the cost imposition discussion by asserting, ‘when there’s a $10 problem, … you [try to] solve that problem for 10 cents and you force your competition to solve it for a thousand bucks’.[50] Using several CCAs to destroy a formation of bombers or a guided missile destroyer is exactly the cost asymmetry Australia requires for effective deterrence by denial.

CCAs provide a pathway to establish combat mass at an affordable price point compared to crewed aircraft. The removal of humans relieves the designers of the ‘engineering and cost disadvantages of accommodating flesh-and-bone pilots who need life support, flight controls, displays, and escape systems’.[51] The reduced price of CCAs will come from the adoption of new manufacturing technologies and opportunities arising from removing human crew, which includes paired back design standards and reduced service life. CCAs can be designed for significantly lower service life and flight cycles, which are significant cost drivers for crewed aircraft.[52] US Air Force research indicates that CCAs may be procured for $1200 USD per pound as compared to crewed fighters, which cost $4000-$6000 USD per pound (20-30 percent of crewed aircraft cost).[53] In contrast, the Australian Government has publicly stated that the target cost of the MQ-28A Ghost Bat CCA is around 10 per cent of a crewed fighter.[54] However, at Senate Estimates on 14 February 2024, AVM Graham Edwards declared that Defence was procuring eight Block 1 Ghost Bats and three Block 2 variants for a total cost of $1 billion, with a capability demonstration scheduled to commence in 2025.[55] 11 aircraft for $1 billion is hardly affordable mass, but this cost data is better interpreted as the cost associated with re-establishing a sovereign aircraft design and manufacturing capability. As more countries progress their CCA programs into production, clearer cost data will become available, but requirements creep, and the desire to build multirole, exquisite CCAs versus focussed and affordable CCAs must be resisted to ensure affordable mass remains achievable.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Australia requires a suite of capabilities that can integrate to generate a credible deterrent effect by raising the cost for an adversary to project military force against Australia. These capabilities must possess enough lethality to influence an adversary's decision, so they conclude that the benefits of attacking Australia do not outweigh the costs. If deterrence fails, these capabilities must be proven and credible to shift from deterrence to response in defence of Australia. In the missile age, Australia’s geographic remoteness and the much-lauded ‘air-sea gap’ no longer provide a sanctuary from attack. Regionally, China possesses an extensive array of ballistic and cruise missiles that constitute a viable means of striking Australia, using systems that originate in mainland China. Given that defence against ballistic missiles presents significant challenges to air-breathing aircraft, Australia's air combat capability must focus on the threat posed by cruise missiles. Augmenting Australia’s crewed fighters with CCAs provides an affordable means to enhance range, lethality and survivability. Using CCAs with the right attributes, CCAs can be used to hold cruise missile launch platforms at risk. Further, CCAs offer Australia a way to swiftly enhance its military deterrence, especially in contrast to long-gestation programs like the nuclear-powered submarine, which will not bolster deterrence until the 2030s.

CCAs possess unique attributes which afford adopting Air Forces opportunities to create lethal systems capable of shifting the cost exchange ratio in their favour. The versatility, autonomy, and affordability of CCAs provide the ADF with a valuable tool for enhancing long-range strike capabilities and countering threats from technologically advanced adversaries. Moreover, CCAs have the potential to impose significant operational costs on aggressors while reducing the risk to human life, which supports Australia's broader deterrence strategy. Given that CCAs can be most effective if considered attritable when being used to penetrate adversary defences, a credible CCA capability must be accompanied by a means of replenishing destroyed aircraft. In the case of Australia, developing a sovereign capability for design and manufacturing that can operate at a minimum viable capacity during peacetime and scale up production for war will be a costly but strategically valuable investment. Overall, CCAs not only enhance Australia’s military resilience but also contribute to a broader, more cost-effective defence posture in the face of evolving regional challenges.

Aiello, Vincent, and Mike Benitez. “The Perfect Wingman.” Fighter Pilot Podcast. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://podcasts.apple.com/au/podcast/fighter-pilot-podcast/id1330534712?i=1000648776430.

Allen, Gregory C, and Isaac Goldston. “The Department Of Defense’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft Program,” August 2024.

Benitez, Mike. “Anduril & General Atomics CCAs.” The Merge. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/the--merge/episodes/E39--Anduril--General-Atomics-CCAs-e2lesms.

Centre for Strategic and International Studies. “Standard Missile-3 (SM-3).” Missile Threat. Accessed October 5, 2024. https://missilethreat.csis.org/defsys/sm-3/.

Commonwealth of Australia. ADF Concept ASPIRE - The Australian Defence Force’s Theatre Concept, Edition 2. Department of Defence, 2023.

———. “APEX: Australian Defence Force Capstone Concept - Integrated Campaigning for Deterrence, Edition 2.” Department of Defence, January 11, 2024.

———. “F-35A Lightning II.” Air Force, November 8, 2023. https://www.airforce.gov.au/aircraft/f-35a-lightning-ii.

———. “F/A-18F Super Hornet.” Air Force, February 17, 2023. https://www.airforce.gov.au/aircraft/18f-super-hornet.

———. “Integrated Investment Program.” Department of Defence, April 17, 2024. https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defence-strategy-2024-integrated-investment-program.

———. “National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 | About | Defence.” Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Defence. Accessed February 17, 2024. https://www.defence.gov.au/about/reviews-inquiries/defence-strategic-review.

———. “National Defence Strategy.” Department of Defence, April 2024.

Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, Senate, AVM Graham Edwards, 2024. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/estimate/27711/toc_pdf/Foreign%20Affairs,%20Defence%20and%20Trade%20Legislation%20Committee_2024_02_14_Official.pdf;fileType="application%2Fpdf."

Dowse, Andrew, Marigold Black, John P. Godges, Caleb Lucas, and Christopher A. Mouton. Australia’s Sovereign Capability in Military Weapons. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2023. https://doi.org/10.7249/PEA2131-1.

Graham, Euan. “Royal Australian Navy Tests the Swiss Army Knife of Missiles.” The Strategist, August 20, 2024. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/royal-australian-navy-tests-the-swiss-army-knife-of-missiles/.

Gunzinger, Col Mark A., Maj Gen Lawrence A. Stutzriem, and Bill Sweetman. “The Need for Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare.” The Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, February 2024. https://www.mitchellaerospacepower.org/app/uploads/2024/02/The-Need-For-CCAs-for-Disruptive-Air-Warfare-FULL-FINAL.pdf.

Hellyer, Marcus. “‘Impactful Projection’: A Porcupine with Very Long Quills.” The Strategist, November 18, 2022. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/impactful-projection-a-porcupine-with-very-long-quills/.

Hellyer, Marcus, and Andrew Nicholls. “‘Impactful Projection’: Long-Range Strike Options for Australia.” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, December 2022. https://ad-aspi.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/2022-12/Impactful%20projection.pdf?VersionId="cvFyjDys7.R5_ZSjRURXZDgSgqpilQ9e."

Hlad, Jennifer. “Imposing Costs on the Enemy.” Air & Space Forces Magazine, May 30, 2017. https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/imposing-costs-on-the-enemy/.

Janes. “CJ-20 (K/AKD-20,CJ-10K/KD-20).” In Weapons: Air Launched. Janes, 2023. https://customer.janes.com/display/JALWA092-JALW. NB Account required for access.

Lee, Caitlin, and Col Mark A Gunzinger. “The Next Frontier: UAVs for Great Power Conflict - Part 1: Penetrating Strike.” The Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, December 2022. https://www.mitchellaerospacepower.org/the-next-frontier-uavs-for-great-power-conflict-part-1-penetrating-strike/.

Missile Threat. “YJ-18.” Accessed September 17, 2024. https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/yj-18/.

Ochmanek, David A. Determining the Military Capabilities Most Needed to Counter China and Russia: A Strategy-Driven Approach. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022. https://doi.org/10.7249/PEA1984-1.

Pope, Charles. “CSAF Outlines Strategic Approach for Air Force Success.” Air Force, August 31, 2020. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2331282/csaf-outlines-strategic-approach-for-air-force-success/.

“Radio Interview, ABC.” Defence Ministers, February 9, 2024. https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/transcripts/2024-02-09/radio-interview-abc.

Rupprecht, Andreas, and Dominguez, Gabriel. “PLAAF’S New H-6N Bomber Seen Carrying Large Missile.” Defence Weekly, October 19, 2020. https://customer.janes.com/Janes/Display/FG_3772109-JDW. NB Account required for access.

Shoebridge, Michael. “As Defence’s Core Functions Fail, What’s the Plan for Change?” Strategic Analysis Australia, November 30, 2023. https://strategicanalysis.org/as-defences-core-functions-fail-whats-the-plan-for-change/.

Tirpak, John. “Experts: CCA Drones Could Cost Less Than $1,200 per Pound.” Air & Space Forces Magazine, September 27, 2024. https://www.airandspaceforces.com/experts-cca-drones-cost-use-maintenance/.

United Kingdom Ministry of Defence. “Royal Air Force Autonomous Collaborative Platform Strategy.” Ministry of Defence, 27 Mar 24. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/66019fa8f1d3a0666832acfc/RAF_Autonomous_Collaborative_Platform_Strategy.pdf.

United States Department of Defense. “Military and Security Development Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023 - Annual Report to Congress.” Accessed September 17, 2024. https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

———. “The 2019 Missile Defense Review - Executive Summary.” Office of the Secretary of Defense. Accessed October 2, 2024. https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Interactive/2018/11-2019-Missile-Defense-Review/The%202019%20MDR_Executive%20Summary.pdf.

———. “The Ballistic Missile Defense System.” United States Department of Defense. Accessed October 2, 2024. https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Interactive/2018/11-2019-Missile-Defense-Review/MDR-BMDS-Factsheet-UPDATED.pdf.

Wills, Colin. Unmanned Combat Air Systems in Future Warfare: Gaining Control of the Air. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

1 Michael Shoebridge, “As Defence’s Core Functions Fail, What’s the Plan for Change?,” Strategic Analysis Australia, November 30, 2023, https://strategicanalysis.org/as-defences-core-functions-fail-whats-the-plan-for-change/.

2 Commonwealth of Australia, “National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 | About | Defence” (Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Defence), 61, accessed February 17, 2024, https://www.defence.gov.au/about/reviews-inquiries/defence-strategic-review.

3 Commonwealth of Australia, “National Defence Strategy” (Department of Defence, April 2024), 37.

4 Marcus Hellyer, “‘Impactful Projection’: A Porcupine with Very Long Quills,” The Strategist, November 18, 2022, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/impactful-projection-a-porcupine-with-very-long-quills/.

5 Commonwealth of Australia, ADF Concept ASPIRE - The Australian Defence Force’s Theatre Concept, Edition 2 (Department of Defence, 2023), 10.

6 Mike Benitez, “Anduril & General Atomics CCAs,” The Merge, accessed September 18, 2024, https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/the--merge/episodes/E39--Anduril--General-Atomics-CCAs-e2lesms.

7 Caitlin Lee and Col Mark A Gunzinger, “The Next Frontier: UAVs for Great Power Conflict - Part 1: Penetrating Strike” (The Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, December 2022), 3, https://www.mitchellaerospacepower.org/the-next-frontier-uavs-for-great-power-conflict-part-1-penetrating-strike/.

8 Colin Wills, Unmanned Combat Air Systems in Future Warfare: Gaining Control of the Air (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 2.

9 Hellyer, “‘Impactful Projection.’”

10 United States Department of Defense, “Military and Security Development Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023 - Annual Report to Congress,” 69, accessed September 17, 2024, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

11 David A. Ochmanek, Determining the Military Capabilities Most Needed to Counter China and Russia: A Strategy-Driven Approach (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022), 6, https://doi.org/10.7249/PEA1984-1.

12 Col Mark A. Gunzinger, Maj Gen Lawrence A. Stutzriem, and Bill Sweetman, “The Need for Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare” (The Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, February 2024), 15, https://www.mitchellaerospacepower.org/app/uploads/2024/02/The-Need-For-CCAs-for-Disruptive-Air-Warfare-FULL-FINAL.pdf.

13 United States Department of Defense, “The Ballistic Missile Defense System” (United States Department of Defense), accessed October 2, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Interactive/2018/11-2019-Missile-Defense-Review/MDR-BMDS-Factsheet-UPDATED.pdf.

14 United States Department of Defense, “The 2019 Missile Defense Review - Executive Summary” (Office of the Secretary of Defense), XIII, accessed October 2, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Interactive/2018/11-2019-Missile-Defense-Review/The%202019%20MDR_Executive%20Summary.pdf.

15 Centre for Strategic and International Studies, “Standard Missile-3 (SM-3),” Missile Threat, accessed October 5, 2024, https://missilethreat.csis.org/defsys/sm-3/.

16 Euan Graham, “Royal Australian Navy Tests the Swiss Army Knife of Missiles,” The Strategist, August 20, 2024, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/royal-australian-navy-tests-the-swiss-army-knife-of-missiles/.

17 United States Department of Defense, “Military and Security Development Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023 - Annual Report to Congress,” 63.

18 Janes, “CJ-20 (K/AKD-20,CJ-10K/KD-20),” in Weapons: Air Launched (Janes, 2023), https://customer.janes.com/display/JALWA092-JALW; Andreas Rupprecht and Dominguez, Gabriel, “PLAAF’S New H-6N Bomber Seen Carrying Large Missile,” Defence Weekly, October 19, 2020, https://customer.janes.com/Janes/Display/FG_3772109-JDW. NB The Jane's website requires an account to access content.

19 Commonwealth of Australia, “F-35A Lightning II” (Air Force, November 8, 2023), https://www.airforce.gov.au/aircraft/f-35a-lightning-ii; Commonwealth of Australia, “F/A-18F Super Hornet” (Air Force, February 17, 2023), https://www.airforce.gov.au/aircraft/18f-super-hornet.

20 Gunzinger, Stutzriem, and Sweetman, “The Need for Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare,” 23–30.

21 United States Department of Defense, “Military and Security Development Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023 - Annual Report to Congress,” 52.

22 “YJ-18,” Missile Threat, accessed September 17, 2024, https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/yj-18/.

23 Gunzinger, Stutzriem, and Sweetman, “The Need for Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare,” 29.

24 Lee and Gunzinger, “The Next Frontier: UAVs for Great Power Conflict - Part 1: Penetrating Strike,” 10.

25 Gunzinger, Stutzriem, and Sweetman, “The Need for Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare,” 7.

26 United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, “Royal Air Force Autonomous Collaborative Platform Strategy” (Ministry of Defence, 27 Mar 24), 5, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/66019fa8f1d3a0666832acfc/RAF_Autonomous_Collaborative_Platform_Strategy.pdf.

27 Marcus Hellyer and Andrew Nicholls, “‘Impactful Projection’: Long-Range Strike Options for Australia” (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, December 2022), 38–42, https://ad-aspi.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/2022-12/Impactful%20projection.pdf?VersionId="cvFyjDys7.R5_ZSjRURXZDgSgqpilQ9e."

28 Gunzinger, Stutzriem, and Sweetman, “The Need for Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare,” 6.

29 Vincent Aiello and Mike Benitez, “The Perfect Wingman,” Fighter Pilot Podcast, accessed September 18, 2024, https://podcasts.apple.com/au/podcast/fighter-pilot-podcast/id1330534712?i=1000648776430.

30 Lee and Gunzinger, “The Next Frontier: UAVs for Great Power Conflict - Part 1: Penetrating Strike,” 15.

31 Lee and Gunzinger, 8.

32 Gunzinger, Stutzriem, and Sweetman, “The Need for Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare,” 1.

33 Lee and Gunzinger, “The Next Frontier: UAVs for Great Power Conflict - Part 1: Penetrating Strike,” 16.

34 Gregory C Allen and Isaac Goldston, “The Department Of Defense’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft Program,” August 2024, 2.

35 Allen and Goldston, 9.

36 Benitez, “Anduril & General Atomics CCAs.”

37 Commonwealth of Australia, “APEX: Australian Defence Force Capstone Concept - Integrated Campaigning for Deterrence, Edition 2” (Department of Defence, January 11, 2024), 22.

38 Lee and Gunzinger, “The Next Frontier: UAVs for Great Power Conflict - Part 1: Penetrating Strike,” 24.

39 Gunzinger, Stutzriem, and Sweetman, “The Need for Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare,” 33.

40 Gunzinger, Stutzriem, and Sweetman, 7.

41 Hellyer and Nicholls, “‘Impactful Projection’: Long-Range Strike Options for Australia,” 15; Commonwealth of Australia, “Integrated Investment Program” (Department of Defence, April 17, 2024), https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defence-strategy-2024-integrated-investment-program.

42 United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, “Royal Air Force Autonomous Collaborative Platform Strategy,” 9.

43 Charles Pope, “CSAF Outlines Strategic Approach for Air Force Success,” Air Force, August 31, 2020, https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2331282/csaf-outlines-strategic-approach-for-air-force-success/.

44 United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, “Royal Air Force Autonomous Collaborative Platform Strategy,” 4.

45 Andrew Dowse et al., Australia’s Sovereign Capability in Military Weapons (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2023), 8, https://doi.org/10.7249/PEA2131-1.

46 Lee and Gunzinger, “The Next Frontier: UAVs for Great Power Conflict - Part 1: Penetrating Strike,” 4.

47 Lee and Gunzinger, 27.

48 Lee and Gunzinger, 10.

49 Lee and Gunzinger, 11.

50 Jennifer Hlad, “Imposing Costs on the Enemy,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, May 30, 2017, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/imposing-costs-on-the-enemy/.

51 Allen and Goldston, “The Department Of Defense’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft Program,” 2.

52 Gunzinger, Stutzriem, and Sweetman, “The Need for Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare,” 23.

53 John Tirpak, “Experts: CCA Drones Could Cost Less Than $1,200 per Pound,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, September 27, 2024, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/experts-cca-drones-cost-use-maintenance/.

54 “Radio Interview, ABC” (Defence Ministers, February 9, 2024), https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/transcripts/2024-02-09/radio-interview-abc.

55 Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, Senate, AVM Graham Edwards, 2024, https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/estimate/27711/toc_pdf/Foreign%20Affairs,%20Defence%20and%20Trade%20Legislation%20Committee_2024_02_14_Official.pdf;fileType="application%2Fpdf."

Defence Mastery

Social Mastery

How can Australia best use collaborative combat aircraft to execute its strategy of denial? © 2024 by . This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.