Two Soldiers, the Great War, and Breadalbane, New South Wales

In a field not far from the village of Breadalbane in New South Wales lies the old graveyard of the Chisholm Memorial Church of St Silas. It is a forlorn place. The gravestones are worn. Some of them are indecipherable. A sargasso of weed surrounds the dated plinths and the youngest is now nearly ninety years old. The old markers stand crooked or lie as clumps of broken marble. Their foundations have been undermined or sunk or shifted with time. Forgotten and overgrown, the clay soil is dominated by unkempt tussocks of Kangaroo and Snow grass.[2] This is a cemetery that tells a story of Australia, and the generations of 19th century names speak to the endeavours of intrepid colonial settlers. The two columns supporting the long disused gates to the graveyard remember two local men, Lindsay Murray and Percy Ings, who fell in the Battle of Fromelles on the same day in 1916. That both were commemorated in this way is testament to how keenly their loss was felt in this tiny hamlet nearly 12,000 miles away. Equally, it speaks to a story of a different and often forgotten time and place in Australian history from where the story resonates still. The monuments are representative of Australia’s connection to the world. A hemisphere from where they now lie, these men are worthy of commemoration.

In 1914, Breadalbane was a small though well-established farming community nestled in the upper reaches of the Lachlan Valley. There were several churches, a store, and a hotel refurbished in 1913, and which remained in service until 1998.[3] Although a long way from France, the Great War would soon catch up with Breadalbane. After Gallipoli, the depleted Anzac divisions were sent to Egypt to recuperate prior to deploying to the Western Front. There, the decision was made to double the size of the force. In addition to the First and Second Divisions, Australia would raise the Fourth and Fifth Divisions. Another division, the Third, was raised in Australia and went to England directly. Numbers were no problem. The successful enlistment campaigns of 1915 generated thousands of new recruits, and these men—the ‘Fair Dinkums’—arrived in Egypt at the same time as those returning from Gallipoli. The Official History recorded that the process of creating the new divisions was straight forward.[4] ‘Sixteen new battalions were required, and it happened that the original force employed had included exactly sixteen’.[5] Accordingly, the sixteen veteran battalions were split. Half the men were posted to form the nucleus of the new units, and they were trained in the British pattern.

The British Army of the Great War was a coalition of national elements with shared values and culture. This extended to military training. The Infantry Training Manual of 1914, used across the Empire, was the standardised curriculum until well into 1916.[6] Indeed, Imperial standardisation was central to Australian practice during the war.[7] Empire infantry used the innovative 1908 pattern cotton webbing set, designed to distribute the weight of equipment evenly.[8] Rifles, grenades, bayonets, and all sundry equipment was standardised.[9] All Empire troops wore the flat Brodie steel helmet. Any soldier from any of the Empire’s divisions could ostensibly be taken from his own formation and effectively placed in another from anywhere else. [10] This is no small accomplishment when one considers the size of the force and how the Australians integrated seamlessly into the construct. Lindsay Murray and Percy Ings are indicative of the 1916 expansion of the AIF.

Lindsay Bertram Murray was a 22-year-old NSW railwayman when he enlisted on 30 July 1915. Murray signed his attestation papers in the nearby township of Goulburn and his next of kin was listed as Mrs Arabella Murray of Mountain Ash farm via Breadalbane.[11] He was the eldest of ten children born to Arabella and Thomas Murray, though his father had passed after an illness on 27 December 1914. Murray senior was buried in the cemetery at Breadalbane where his son was later commemorated.[12] Lindsay Murray was educated at Breadalbane Public School.[13] His papers indicate he was 5’6” tall. He weighed 148lbs and had brown hair, blue eyes, and a fair complexion.[14] A studio portrait of Murray is held by the Australian War Memorial, and it shows a young man wearing an Australian slouch hat staring into the distance.[15] Reaching out across the longue durée, there is something of the devil-may-care attitude in Murray’s expression. It may well personify the egalitarian digger of Charles Bean’s Anzac legend. Murray was allocated the service number 3555 and initially posted to the 11th reinforcements for the 4th Infantry Battalion of the First Australian Division. He departed Australian waters on HMAT A17 Port Lincoln on 13 October 1915. In Egypt he was reallocated to A Company of the 53rd Australian Infantry Battalion on 16 February 1916. Murray’s battalion and parent formations were the 14th Infantry Brigade and Fifth Australian Division. It trained for the next four months in Egypt. Lindsay Murray’s 53rd Battalion would have been his ‘home’.

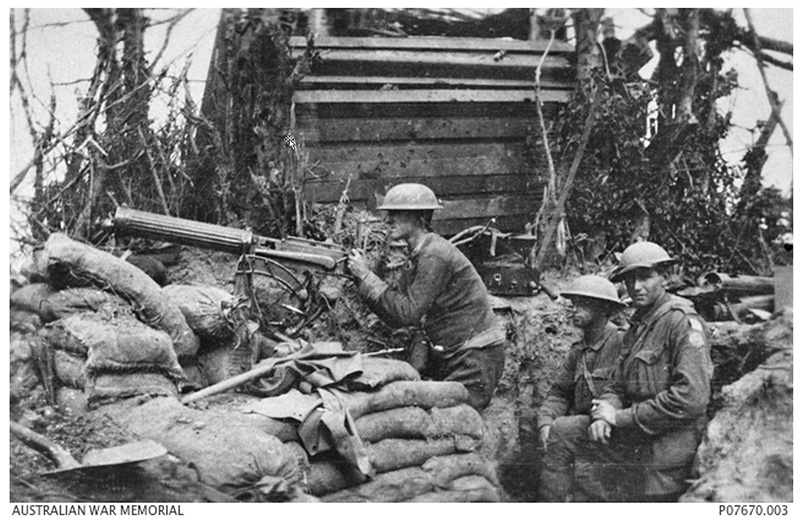

Percy Edwin Ings’ image depicts an earnest young man staring into the camera from under the peaked cap as issued early in the war.[16] The second eldest of eight children to Edwin and Emily Ings, Percy Ings was raised on a property named ‘Cede Ceàrn’ in Breadalbane where he attended the Public School. He was the same age as Murray, and they were at school during the same period. Ings completed a carpentry apprenticeship and was in the employment of the Ibbotson and Portus Timber Yard in Goulburn prior to enlisting. His papers indicate that he was 5’3” tall and weighed 140lbs. He had brown hair and eyes, and a fair complexion.[17] He enlisted at Liverpool in Sydney on 9 July 1915 and was allocated the service number 909 in the 30th Australian Infantry Battalion. The 30th Battalion was raised as part of the 8th Brigade at Liverpool Camp on 5 August 1915 and embarked on HMAT A72 Beltana on 9 November 1915. Ings was transferred to the 8th Australian Machine Gun (MG) Company when it was formed on 19 March 1916 in Egypt.[18] The weapons were used as an adjunct to artillery and would ‘sweep the ground’ ahead of an advance. The British Army had a deep appreciation of the trigonometry and geometry associated with sighting and directing plunging gunfire.[19]

MG Companies comprised a headquarters section and four sections of four Vickers guns each.[20] The Vickers machine gun was a legendary weapon and served the British and Commonwealth defence forces for more than sixty years. The weapon was mounted on a tripod and cooled by water held in a jacket around the barrel. The gun weighed 28.5 lbs, and the water for the jacket around the barrel weighed 10 lbs. The tripod weighed 20 lbs. Rounds for the weapon were assembled into a canvas belt, and the gun had a cyclic rate of fire of 500 rounds per minute.[21] The detail is important. The firepower available to a MG company in the attack was decisive, and well understood within the BEF. However, the Germans had a deeper appreciation of how effective machine guns were in defence. [22]

The First and Second Australian Divisions arrived in France in March 1916. The Fourth Division followed. The Fifth Division was the last to arrive in late June, under the command of Major General James Whiteside McCay.[23] McCay, a former Australian Federal politician, lawyer, and citizen soldier had a formidable intellect. He was a respected trainer and had connections to the High Commission in London and to the Australian Minister of Defence, George Pearce. On paper, McCay was a good choice to command. He had led the 2nd Australian Brigade on Gallipoli where he was wounded at Krithia on 8 May 1915. Bean records McCay standing on the parapets calling “Come on Australia!” and urging his men forward as Turkish bullets landed around him.[24] In addition to his intelligence and drive, McCay genuinely cared for his soldiers. He demanded and received high standards from them.[25] He was, however, unsuited to the command in which he served—for despite his fine qualities, McCay was dour, inflexible, and unable to engage with his men in a way that they understood him.

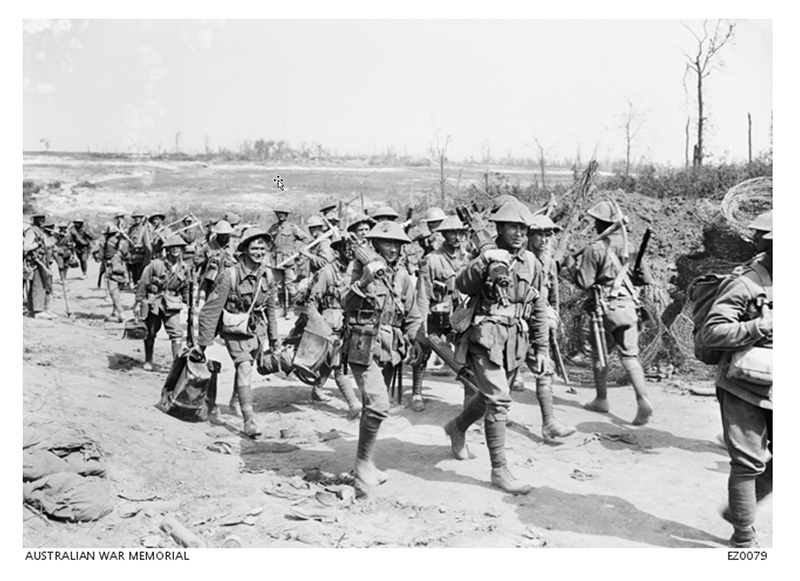

The Fifth Division arrived in France on 25 June 1916 five days before the Somme offensive. The Division’s brigades entrained to the Armentières ‘nursery’ sector in northern France to acclimatise. The Australians were not ready for combat and would not participate in the coming battle. On 1 July 1916, the opening day of the Battle of the Somme proved to be the worst day in the British Army’s history. Attacking without adequate artillery support against uncut barbed wire and well-defended German positions, the BEF suffered 60,000 casualties in twenty-four hours, 20,000 of whom were killed.[26] Little was achieved. Notwithstanding this, the General Officer Commanding, Sir Douglas Haig, insisted that the offensive continue to relieve pressure on the French fighting around Verdun.[27] The Australian divisions waited fifty miles to the north. It would not be long before they joined in.

Though it was the last to arrive in France, the Fifth Division would be the first into action. [28] The division’s diary highlights it was seconded to Lieutenant General Richard Haking’s XI Corps of the British First Army on 13 July 1916 to participate in a diversionary demonstration.[29] The scheme paired the Australians with the British 61st Division to assault a German salient north of the Somme. It was defended by a strong position known as the ‘sugarloaf’. Behind the sugarloaf salient lay the French village of Fromelles for which the operation would later be named. The water table in this part of northern France was very high so defensive positions were built up. The ground across which the infantry would assault was flat and devoid of cover, and in front of the sugarloaf no man’s land was 400 metres wide. There was inadequate artillery support and assumptions were made about the effect that shellfire would have on the prepared German defences, particularly the barbed wire and depth of the German dugouts. The 5th Division was inexperienced and the 61st Division significantly understrength. The German line was manned in depth by the experienced 6th Bavarian Reserve Division comprising infantry and machine gunners all aware of the build-up. The Germans shelled the preparations, causing casualties before the attack even started.[30] Finally, orders were received during the morning of 19 July for the operation to proceed; and in the early evening, the Fifth Australian and 61st British Divisions left their trenches to cross no man’s land. Both divisions deployed three brigades with two battalions per brigade in the attack. In the Fifth’s circumstance, the 8th Brigade was on the left (in the north), the 14th Brigade was in the centre, and the 15th Brigade abutted the 61st Division opposite the sugarloaf. In the European summer, there were about three hours of daylight remaining.

The 8th Brigade, including the 8th MG Company with Private Percy Ings in its number, quickly seized the German trenches, and then pushed forward to set up a series of outlying posts behind the German lines. They were incredibly exposed. The 14th Brigade was not as fortunate. The wire in front of the German lines was not completely cut, and the advancing 53rd Battalion was exposed to machinegun fire from the sugarloaf on its flank. The brigade managed to enter and take the German trenches, but it was costly. The 53rd Battalion’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Ignatius Norris, was killed in the advance.[31] And somewhere in the maelstrom, Corporal Lindsay Murray was wounded. On the right, the 5th Division diary indicates that ‘machine gun fire from the sugarloaf worried the troops directly they came over the parapet’.[32] This is an understatement. The 15th Brigade was cut down as it left the trenches and then as it tried to get through the unbroken wire. Veteran Hugh Downing wrote that ‘the sandbags were splashed with red, and red were the firesteps, the duckboards, the bays. And the stench of stagnant pools of the blood of heroes is in our nostrils even now’.[33] The 15th Brigade’s commander, Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliott, wept as he witnessed his men struggling to get back under fire.[34] The 61st Division failed to make any headway at all.

During the night of 19-20 July, the Australians came under counterattack. The 8th Brigade was exposed to German machinegun fire from the northeast and the 14th Brigade was attacked and shelled in turn. The 15th Brigade and 61st Division was ordered to sortie against the sugarloaf again, but the order did not reach the 61st in time. The 15 Brigade went on and faired as badly as it did in the first assault.[35] By the next morning the situation was parlous, and orders were relayed to each brigade to abandon their gains and withdraw. And so, the survivors of the 5th Division retreated under fire as dawn broke the next morning. The 8th Brigade departed first, then the 14th Brigade which received its orders late. Then came the many stragglers of the 15th Brigade which continued to drift in from no-man’s land. Bean’s diary highlighted that the 8th MG Company lost eight Vickers guns and their crews in the withdrawal.[36] Among their number was Percy Ings, the young man’s remains were later recovered and interred at the Anzac Cemetery at Sailly-sur-la-Lys, near Armentières.[37]

The scene was harrowing. It was summer, the sun was shining, the weather was warm. The men lay where they fell in that interminable period. A few were wounded, and Lindsay Murray was among these. His record listed him as missing on 19 July 1916.[38] For two days, he suffered under the sun and the stars, through the pain, and swelling and fear; through the suppuration and the thirst. Murray’s fortitude was remarkable. He dragged himself, or was found and carried, back into the Australian lines. His record subsequently reads ‘22 July 1916 CCS Admitted GSW thigh’, but it was too late.[39] His wound was gangrenous, and in the era before penicillin it was a death sentence. In Murray’s short life there was now no time, but he had an interminable interval to think. He surely knew what was to come. On 24 July Murray was transferred to a General Hospital, ‘GSW R thigh gas gangrene’, and on 28 July 1916 he finally succumbed. [40] Lindsay Murray was buried at Wimereux Cemetery in France on the same day.[41]

At Fromelles, the Fifth Division suffered 5,533 casualties.[42] Haking blamed the Australians entirely:

The artillery preparations were adequate. There were sufficient guns and sufficient ammunition. The wire was properly cut, and the assaulting battalions had a clear run into the enemy’s trenches. The Australian infantry attacked in the most gallant manner and gained the enemy’s position, but they were not sufficiently trained to consolidate the ground gained. They withdrew and lost heavily doing so.[43]

Bean disagreed: ‘The reasons for this failure seem to have been loose thinking and somewhat reckless decision on the part of the higher staff…it is difficult to conceive that the operation, as planned, was ever likely to succeed’.[44] Whatever the circumstance, the Fifth Division was destroyed at Fromelles and so was McCay’s reputation.[45] He sealed his fate as a leader when he enforced orders from Army Headquarters that called a halt to any localised truce to gather in the wounded.[46]

In days, the government notified the Ings and Murray families in Breadalbane. Both wrote to the Army Records Office. The letters, written in the beautiful script of the day, call poignantly across the years seeking news of where their sons had been laid to rest. The seasons followed seasons. On Armistice Day—11 November 1918—Charles Bean returned to the Fromelles battlefield. It was as Golgotha: ‘We found the old No-Man’s-Land simply full of our dead,’ his diary reads. ‘The skulls and bones and torn uniforms were lying about everywhere’.[47] Not long after the war these men were gathered and laid to rest in the VC Corner Cemetery. Australia and the Empire welcomed its other sons home. On 6 September 1919, the Goulburn Evening Penny Post recorded the arrival of several returned soldiers back to Breadalbane, among them Corporal Cecil Ings, brother of Percy Ings.[48] The district turned out and a reception was held in the Breadalbane Hall. The Ings family held a dinner for invited family and friends in their home, and the years rolled by.

Percy Ings and Lindsay Murray were memorialised on the gateposts of the church. The changes came and some were large, but most were imperceptible. In time, Percy Ings’ father, Edwin, passed and was laid to rest near where his son was commemorated.[49] Arabella Murray left the world, too, and rested beside her departed husband.[50] The foundations of the Church of St Silas were damaged, and the church was rebuilt elsewhere. But the gates at the cemetery stood resolute in the sun and the rain, and sometimes the snow, for a century, and one day—no history could state exactly when—it was no longer a British world. But it did not matter. For Australia remembers Percy Edwin Ings and Lindsay Bertram Murray still.

Australian War Memorial

AWM4 1/50/5 Part 3, General Staff, Headquarters 5th Australian Division, July 1916, Report on Operations 19 July 1916, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1338920

AWM38 3DRL 606/7/1, Records of Australian Official Historian - May 1915, p. 50, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1378257

AWM EZ0079 Image, Australian Machine gunners, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C46382

AWM E05990 Image, Fromelles, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C55124

AWM H16396 Image, Men of the 53rd Battalion. [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1574

AWM P07670.003 Image, MG in action…, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1226545

AWM P05899.004 Image, Studio portrait of 3555 Lance Corporal Lindsay Bertram Murray. [Online} available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1207859

AWM ARTV05167, A Call from the Dardanelles, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/ARTV05167

AWM, Battle of Fromelles, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/fromelles

AWM, Gallipoli, [Online] available at: http://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/gallipoli/

Official Sources

Australian Government: Murray Darling Basin Authority, The Lachlan, [online) available at: https://www.mdba.gov.au/basin/catchments/southern-basin-catchments/lachlan-catchment accessed 13 September 2022.

National Archives of Australia (NAA), Service Record of No. 909 Private Percy Edwin Ings, 8th Machine Gun Company AIF, [Online] available at: https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=7362102

National Archives of Australia (NAA), Service Record of No. 3555 Lance Corporal Lindsay Bertram Murray, 53rd Infantry Battalion AIF, [Online] available at: https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=7992216

State Government of New South Wales (NSW): Nature Conservation Council of NSW, Graham, M., Watson, P., & Tierney, D., Fire and the Vegetation of the Lachlan Region, Sydney, 2013, [Online] available at: https://hotspotsfireproject.org.au/download/fire-and-the-vegetation-of-the-lachlan-region.pdf

State Government of New South Wales (NSW): NSW Department of Planning and Environment, The Lachlan Valley in Profile, [Online] available at: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/water/water-for-the-environment/lachlan

State Government of New south Wales (NSW): NSW Department of Planning, Tracey, J., Upper Lachlan Shire Community Heritage Study 2007 – 2008, Upper Lachlan Shire Council and Heritage Branch, Sydney, 2009, [Online] available at: https://heritagensw.intersearch.com.au/heritagenswjspui/bitstream/1/4084/1/H10374%20-%20UPPE.pdf

The UK National Archives, UK Public General Acts, Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900, [Online] available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/63-64/12/contents/enacted

The UK National Archives, War Office Instructions (WO) 293/1: Army Council: Instructions, Army Orders 413 and 414 of 22 October 1915, [Online] available at: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C1823200

The UK National Archives, War Office,Army Orders, 24/899, Army Establishments of 1914, [Online] available at: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C4401773

Virtual War Memorial of Australia, service details pertaining to No. 909 Private Percy Edwin Ings, 8th MG Company, [Online] available at: https://vwma.org.au/explore/people/282362

War Office Stationery Series (SS)106, Notes on the Tactical Employment of Machine Guns and Lewis Guns, His Majesty’s Stationary Office (HMSO), London, March 1916.

War Office Stationery Series (SS)135, The Training and Employment of Divisions, His Majesty’s Stationary Office (HMSO), London, February 1918.

War Office, Field service Manual: 1914 Infantry Battalion, His Majesty’s Stationary Office (HMSO), London, October 1914.

War Office, Handbook for the ·303-In. Vickers Machine Gun (Magazine Rifle Chamber) Mounted on Tripod Mounting, Mark IV, His Majesty’s Stationary Office (HMSO), London, October 1914.

Published Articles and Books

Bean, C.E.W., The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Vol. I. The Story of Anzac, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1941, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1416845

Bean, C.E.W., The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Vol. II. The Story of Anzac, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1941, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1416846

Bean, C.E.W., The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Vol. III. The Australians in France 1916, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1941, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1416847

Bean, C.E.W., Gallipoli Mission, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1948, [Online] available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1416967

‘Breadalbane District News’, in the Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 6 September 1919, p. 4. [Online] available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/98906272?searchTerm=percy%20ings%20breadalbane

‘Breadalbane District News’, in the Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 11 December 1924, p. 2. [Online] available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/99282074

Breadalbane District News’, in the Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 2 October 1934, p. 2. [Online] available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/103667896?searchTerm=arabella%20murray%20breadalbane

Bridge, C. and Fedorowich, K., ‘Mapping the British World’, in The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, Vol. 31, No. 2, 2003, pp. 1-15.

Burness, P., (ed.), The Western Front Diaries of Charles Bean, Australian War Memorial and New South Books, Sydney, 2018,

Cader, A., What the History of Australian Independence can tell us about Britain’s Journey Ahead, The Oxford University Politics Blog, 15 January 2020, [Online] available at: https://blog.politics.ox.ac.uk/what-the-history-of-australian-independence-can-tells-us-about-britains-journey-ahead/

Cashin, P. and McDermott, C. John, ‘Riding on the Sheep’s Back: Examining Australia’s Dependence on Wool Exports’, in The Economic Record, Vol. 78, No. 242, September, 2002, pp. 249-263.

'Chisholm, James (1806–1888)', Obituaries Australia, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, in Australian Town and Country Journal, 30 June 1888, p 44, [Online] available at: https://oa.anu.edu.au/obituary/chisholm-james-15705/text26903

Clarke, F.G., Australia: A Concise Political and Social History, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Sydney, 1992.

Connor, J., ‘The Empire’s War Recalled: Recent Writing on the Western Front Experience of Britain, Ireland, Canada, Australia, India, New Zealand, South Africa and the West Indies’, in History Compass 7/4, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2009.

Connor, J., Anzac and Empire: George Foster Pearce and the Foundations of Australian Defence, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2011.

Dennis, P. et al, The AIF Project, University of New South Wales, [Online] available at: https://www.aif.adfa.edu.au/showPerson?pid=219433

Eddy, J., ‘The Crisis of Empire and Colonial Nationalism’, in John Moses and Christopher Pugsley (eds.), The German Empire and Britain’s Pacific Dominions 1871-1919: Essays on the Role of Australia and New Zealand in World Politics in the Age of Imperialism, Regina Books, Claremont, California, 2000.

Ellis, A., The Story of the Fifth Australian Division: Being an Authoritative Account of the Division's doings in Egypt, France and Belgium (originally published 1920), Forgotten Books, London, Reprinted 2018.

Fewster, K. (ed.), Bean’s Gallipoli: the Diaries of Australia’s Official War Correspondent, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2007.

Gammage, B., The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War, Penguin Publications, Ringwood, 1975.

Lifestyle and Travel, ‘Breadalbane’, in the Sydney Morning Herald, 8 February 2004, [Online] available at: https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/breadalbane-20040208-gdkpzb.html

Lee, R., The Battle of Fromelles 1916, Big Sky Publishing, Newport, Sydney, 2010.

Loe, Louise et al, Remember Me to All: The archaeological recovery and identification of soldiers who fought and died in the Battle of Fromelles, 1916, Oxford Archaeological Monograph No. 23, Oxford, 2014.

Loe, L., ‘Fromelles - Recovered, identified, remembered: the fallen of World War I’, in Current World Archaeology, Issue 68, Vol. 6 No. 8, [Online] available at: https://www.world-archaeology.com/features/fromelles/

McMullin, R., Pompey Elliot, Scribe Publications, Melbourne, 2007.

MacQuarie Dictionary Online, etymology of the phrase ‘Fair Dinkum’, in the MacQuarie Dictionary Blog, 2019, [Online] available at: https://www.macquariedictionary.com.au/blog/article/573/

Mason, A. ‘The Australian Constitution 1901—1988, Australian Law Journal, Volume 62, October 1988.

Newton, D., Hell bent: Australia’s Leap into the Great War, Scribe Publications, Sydney, 2014.

Parkes, Sir Henry, The Federation Conference Speech, Melbourne, 6 February 1890, [Online] available at: http://foundation1901.org.au/the-crimson-thread-speech/

Pedersen, P.A., The ANZACS: Gallipoli to the Western Front, Penguin Group, Melbourne, 2007.

Reed, A.W., Place-names of New South Wales, their Origins and Meanings, Halstead Press, Sydney, 1969.

Robson, L.L., The First A.I.F.: A Study of its Recruitment 1914-18, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1982.

Serle, G., 'McCay, Sir James Whiteside (1864–1930)', in Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 1986, [Online] available at: https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/mccay-sir-james-whiteside-7312/text12683

Sheffield, G. & Bourne, J. (eds), Douglas Haig: War Diaries and Letters 1914-1918, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 2005.

St Silas Anglican Church, Breadalbane, NSW, [Online] available at: https://www.churchesaustralia.org/list-of-churches/locations/new-south-wales/a-b-towns/directory/8799-st-silas-anglican-church

Stanley, P., The Crying Years: Australia’s Great War, NLA Publishing, Canberra, 2017.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 March 1865, ‘The Pursuit of the Bushrangers: Ben Hall’s whereabouts’, first reported in the Yass Courier, 1 March 1865, [Online] available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13103041

Wray, C., Sir James Whiteside McCay: a turbulent life, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2002.

1 Sir Henry Parkes at the Federation Conference in Melbourne 6 February 1890.

2 State Government of New South Wales (NSW): Nature Conservation Council of NSW, M. Graham, Fire and the Vegetation of the Lachlan Region, Sydney, 2013, p. 24. The grasses depicted are themeda australis (Kangaroo Grass) and poa sieberiana (Snowgrass).

3 Tracey, J., Upper Lachlan Shire Community Heritage Study 2007 – 2008, Upper Lachlan Shire Council and Heritage Branch, 2009, p. 65.

4 Bean devotes a chapter to the doubling in the OH, Vol. III, pp. 32-68.

5 Bean, OH, Vol III, p. 36.

6 Field service Manual: 1914 Infantry Training (Four Company Organization), His Majesty’s Stationary Office (HMSO), London, October 1914.

7 John Connor, Anzac and Empire: George Foster Pearce and the Foundations of Australian Defence, Melbourne ,2011.

8 Loe, p. 10.

9 Loe, p. 14.

10 By the middle of 1916, the UK had fielded 58 divisions in France under the banner of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). These comprised four Australian, four Canadian, one New Zealand, the Naval Division, and 48 British Infantry Divisions. The final Australian 3rd Division remained training in UK on the Salisbury Plain until late 1916.

11 The Murray family was well known in the district and a Mountain Ash Road near Breadalbane still exists today.

12 Professor Peter Dennis et al, The AIF Project, University of New South Wales.

13 The school remains open in 2022. Breadalbane Public School, [Online] available at: https://breadalban-p.schools.nsw.gov.au

14 National Archives of Australia (NAA), Service Record of Lindsay Bertram Murray, 53 Infantry Battalion AIF

15 AWM P05899.004, Studio Portrait of LCPL Lindsay Bertram Murray.

16 Virtual War Memorial Australia, No. 909 Private Percy Edwin Ings.

17 National Archives of Australia (NAA), Service Record of No. 909 Private Percy Edwin Ings.

18 NAA, Service Record Percy Ings.

19 Appendix A, SS106, Notes on Indirect Fire, pp. 20-26, provides a great level of detail associated with the application of fire against adversaries beyond visual range.

20 Army Orders 414 of 22 October 1915.

21 Specifications taken from: Handbook for the ·303-In. Vickers Machine Gun (Magazine Rifle Chamber) Mounted on Tripod Mounting, Mark IV, London, October 1914.

22 Even so, as early as 1907 British trials had indicated that two machine-guns would destroy a battalion in the open in only a minute if the troops did not seek cover. See: Dominic Graham, in Tim Travers & Chris Archer (eds.), Men at War: Politics, Technology and Innovation in the Twentieth Century, New Jersey, 2011, p. 74.

23 Geoffrey Serle, 'McCay, Sir James Whiteside (1864–1930)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 1986.

24 Bean, OH Vol. II., p. 27, Bean was present during this fighting, and he recalled that he knew this battlefield better than any other save Pozières in France.

25 Serle, 'McCay, Sir James Whiteside (1864–1930)'.

26 See Martin Middlebrooke’s defining The First Day on the Somme, London, 1971.

27 Gary Sheffield & John Bourne (eds), Douglas Haig: War Diaries and Letters 1914-1918, London, 2005, p. 203.

28 Bean, OH, Vol. III, pp. 328–333.

29 AWM4 1/50/5 Part 3, General Staff, Headquarters 5th Australian Division, July 1916, Report on Operations 19 July 1916.

30 Bean, OH, Vol. III, pp. 356-7.

31 Bean, OH, Vol. III, pp. 368-9.

32 AWM4 1/50/5 Part 3, Report on Operations 19 July 1916,

33 Downing, To the Last Ridge: The WW1 Experiences of W.H. Downing, Sydney, 2000, p. 35.

34 Ross McMullin, Pompey Elliot, Melbourne, 2002, p. 224.

35 Wray, Sir James Whiteside McCay, pp. 189-190.

36 Peter Burness (ed.), The Western Front Diaries of Charles Bean, Sydney, 2018, p. 115.

37 NAA, Service Record Percy Ings.

38 NAA, Service Record Lindsay Murray.

39 CCS: Casualty Clearing Station. GSW: Gun Shot Wound.

40 NAA, Service Record Lindsay Murray.

41 The source for Lindsay Murray’s image AWM P05899.004 incorrectly lists his place of death as Pozières. The error may be due to his ienlistment as a reinforcement in the 4th Battalion of the 1st Australian Division. Murray’s service in the 53rd Battalion and place of burial clearly indicate he was killed at Fromelles.

42 Bean, OH, Vol. III, p. 442.

43 Bean, OH, Vol. III, p. 444.

44 Bean, OH, Vol. III, p. 444.

45 Wray, Sir James Whiteside McCay, p. 204.

46 Bean, OH, Vol. III, pp. 439-440.

47 Burness, The Western Front Diaries of Charles Bean, p. 618.

48 ‘Breadalbane District News’, in the Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 6 September 1919, p. 4.

49 ‘Breadalbane District News’, in the Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 11 December 1924, p. 2.

50 ‘Breadalbane District News’, in the Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 2 October 1934, p. 2.

Social Mastery

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.