The Magnificent War Memorial at Coolamon, New South Wales

Warfare is no thing of glamour and no cause for glorification[1]

In the Riverina district, on the flat and fertile plains of central New South Wales, the canola crops blossom in the cold of early spring, and the fields are carpeted in gold for as far as the eye can see. This is wonderful country. In the paddocks, the Merino flocks feed and jostle, and on the slight undulations of the landscape, the perennial waters flow. Along the banks of the creeks and rivers lie stands of apple box, red river gum, and still smaller clumps of stringybark, candle bark, and broadleaf peppermint and wattle.[2] The azure skies watch over it all. The fields are watered by the Murrumbidgee and its many tributaries, from a source high in the Australian Alps, winding down from the alpine regions of the eastern ranges, and eventually to the south-west slopes of NSW. They head west across the riverine plains to finally peter out at their confluence with the River Murray in the west. All along the way farming communities have grown and prospered, and some of them still hark to a time when Australia ‘rode on the sheep’s back’.[3]

Coolamon is one of these places. Settlers coming to the traditional Wiradjuri lands south of the Kindra and Redbank Creeks in the 1840s immediately saw the potential of the region. A stock property was established by Mr J Atkinson in 1848.[4]

The district was surveyed by the NSW Colonial Government and a settlement named ‘Coolamon’ was founded. It is an appropriate name for this fertile region. Coolamon is an Aboriginal word describing a shallow wooden dish used for a multitude of purposes including carrying water and grain.[5] Both are plentiful in the district. The railway arrived in 1881, and the Coolamon station was completed a decade later. By the turn of the 20th century, Coolamon was a thriving community with a population of over 2,000. In addition to the railway station, there was a post office, several banks, a hospital, and school.

The sense of community in Coolamon is strong and the splendour of the village is immediate. Once, many years ago, I rode a touring bicycle into this beautiful township and found a wondrous vista of Australia’s Edwardian and Georgian age. It was a Sunday afternoon, and the streets were wide and quiet, and the wide awnings put midnight on the windows of the shops in the middle of the afternoon. The red brick buildings are sturdy and attractive. They are fine buildings from an earlier era and fit for purpose still. Each conveys a sense of determination and diligence,e and the hard work that has contributed to the prosperity of Australia for more than a century. Along the centre of the main street, the median strip is expansive and manicured. At its northern end stands the war memorial, and there the sense of the nation’s deeper sacrifice is more striking still.

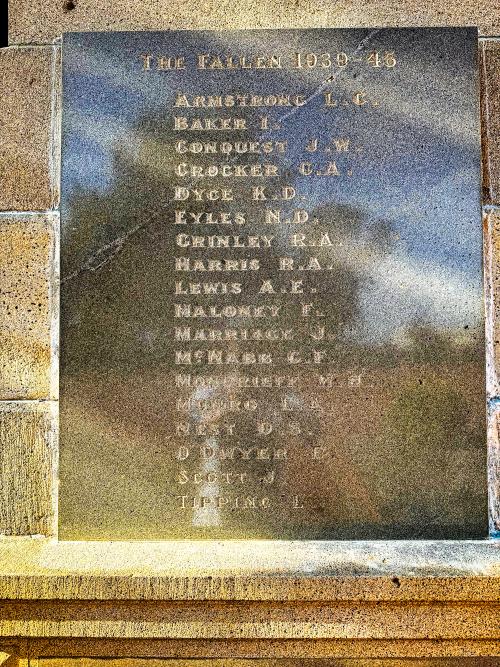

The Coolamon War Memorial is a place of commemoration that stands in perpetuity in Cowabbie Street's green heart. This is a solemn place, but at the same time open and welcoming, and it evokes the sacrifices of generations gone before. The inscriptions share tales of courage and loss, and invite quiet reflection. As it is in every district across Australia, the Coolamon roll of honour calls to us from across the ages. Listen. Hear them: ‘Armstrong, Baker, Conquest, Dyce, Eyles, Grinley, Harris’; and again: ‘Killon, Lucas, Meadows, Munro, Monaghan, Murphy’; they stand with us still. Yet more: ‘Pearce, Roach, Ralph, Rogers, Renehan’. They are here in this place, and the sense of where these young men and women served and fell so far from home in order that we might live as we do is strong and deep inside me.

The obelisk—for that is the form of this and so many monuments across NSW[6]—reveals a pantheon of names, almost overwhelming in their number, but every one with his or her own story in the tapestry of this fine community. They call from across the ages from places famous in our national memory. Every conflict is represented, the clarion call to arms has always been heard in this town: the Boer War, the ‘Great War’, the Second World War, Korea and Vietnam, Australia’s great many peacekeeping missions, and the most modern tragedies of the 21st century’s ‘War on Terror’. There are stories of quiet, diligent service, but also of heroism and sacrifice, though one must look more intently to discover the difference, because in their common commemoration, rank and recognition are not distinguished. This is as it should be, but it is fitting that we might know just a little more than what is depicted on a list.

At Anzac, on the afternoon of 6 August 1915, an operational diversion was launched which would become one of the most important Australian actions of the First World War. So named for the single tree that stood on a crest above the Turkish trenches, the Battle of Lone Pine sought to distract the efforts of New Zealand and Australian troops elsewhere as they worked to force a breakout from the Anzac perimeter onto the heights of the Sari Bair Range at Gallipoli.[7] Launched by the 1st (New South Wales) Infantry Brigade late in the afternoon with the setting sun sinking into the serene Aegean Sea behind them, Australian forces immediately encountered formidable entrenched Turkish positions roofed over with pine logs. Breaking through, the men lowered themselves into the galleries below to clear their adversaries out. It took four days of savage hand-to-hand fighting in the dark, against determined counter-attacks, and with a loss of over 2,000 Australian lives.[8]

A young 4th Battalion soldier from Coolamon distinguished himself in the course of the action. The name Kelly is depicted in the centre of the memorial’s list of Great War fallen, but the details of this man’s death are not apparent. No. 1577 William Patrick Kelly enlisted into the 3rd reinforcements of the 4th Battalion, 1st Brigade, First Division, Australian Imperial Force (AIF), on 16 December 1914.[9] William Kelly was a slender 5’8” tall and 10 stone 8 pounds (1.73m/67kg). He was 21 years of age. Kelly’s service record indicates that he was a carpenter, and that his father was a pastoralist from Coolamon where the young William Kelly had grown up. When he enlisted, he was training as a dental technician in Goulbourn, and this is the employment that Bean’s Official History details.[10] William Kelly had fair hair, brown eyes and a fair complexion.

William Kelly fought through with his mates at Lone Pine on 6 August 1915. The 1st Australian Brigade (including Kelly’s 4th Battalion) very quickly entered the Turkish positions, and there followed a night of depraved, indescribable combat as the Australians secured the line. Bean indicates that by the next morning, the 4th Battalion had established a barricade in the extreme north of the Lone Pine trench system, and a fierce bombing duel started between the opposing sides.[12] The Australians held sway, catching and throwing the Turkish bombs back over the cordon as they sailed over the top. It was terribly dangerous work, and William Kelly stood with these men as they repulsed the Turks for some hours. As time went on, almost all of the Australians were killed or wounded, though Kelly remained steadfast.

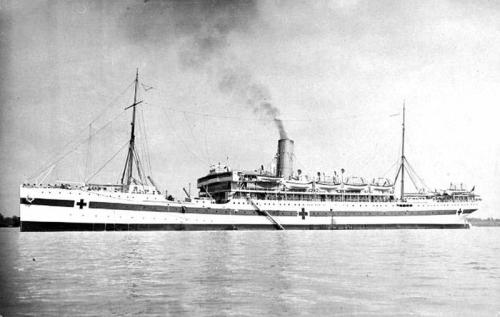

Eventually, Kelly too was wounded when a bomb he had retrieved exploded in his hands. William Kelly was evacuated to the hospital ship Delta with severe shrapnel injuries to his arms and face. His hands were amputated, but it was too late. William Patrick Kelly died of wounds on 11 August 1915, and he was buried at sea. For his gallantry at Lone Pine, Kelly was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. The citation reads:

For conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty on 7th August, 1915, at Lone Pine (Dardanelles). While the wounded were being removed from the trench, the enemy commenced a severe attack by bomb throwers. Private Kelly, with great pluck, met it by collecting and throwing back the enemy’s unexploded bombs, until one burst in his hands, inflicting severe injuries. His gallantry and self-sacrifice undoubtedly saved many of the wounded.[13]

On the opposing side of the Coolamon obelisk is another tragic list from a different conflict, only 25 years on from William Kelly’s war. On the outbreak of this Second World War in 1939, Coolamon again answered the call. As the conflict intensified, Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) aircrews were among the first Australians to head overseas to Britain's aid. Soon, when the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) was established to provide trained aircrews to fight with the RAF, young Australians jumped to the cause.

Australian Air Force recruits received elementary training at air bases around Australia. Many were then sent overseas for advanced training. They went on to fly in both Australian and other Commonwealth squadrons under the scheme.[15] One name from the Coolamon roll of honour served among these crews in the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command, which was arguably the most dangerous service in the conflict. Kenneth Douglas Dyce was born in Coolamon on 14 June 1921, and grew up on the family farm ‘Stratholan’ off Millwood Road, Coolamon. Ken Dyce attended the local public school and Wagga High School before gaining employment as a bank clerk prior to enlisting into the RAAF as an EATS aircrew trainee on 19 July 1941.[16] Dyce was 20 years old, 5’6” (167cm) tall and weighed 138lbs (62.5kg). He had a fair complexion, blue eyes, and auburn hair. [17]

Dyce embarked by sea from Sydney on 28 March 1942 and commenced training under the EATS on the wide open plains of Winnipeg in Canada on 30 April. He graduated as an air navigator and proceeded by ship once more to the UK, where he was posted to 27 Operational Training Unit for specialist training commencing on 8 December 1942.[20] Ken wrote to his mother about the training on 28 February 1943: ‘We have been flying every night until recently … I have been getting good assessments all through, and am very pleased with myself but am still not overconfident, as I know I can improve a bit yet … When we do finish training here, in the next few days, I hope, we will get about ten days leave, and then – ops [operations]’.[21]

Ken Dyce did indeed finish his course and proceeded to 1656 Conversion Unit on 20 March 1943 for conversion onto the Avro Lancaster heavy bomber. There followed a posting to 460 Squadron RAAF, No. 1 Group, RAF Station Binbrook. Dyce was there for a month. He fell from the skies with his crew in their burning Lancaster serial number W4984, shot down during the night of 24-25 May 1943 over Holland.[22] There were no survivors. He was laid to rest at Schoonebeek General Cemetery[23] with his six crewmates where he still rests a world away; the headstone reads: ‘Greater Love hath no man than this …’ St John XV.13. But Ken Dyce is a son of Coolamon and he is remembered in the township to this day.

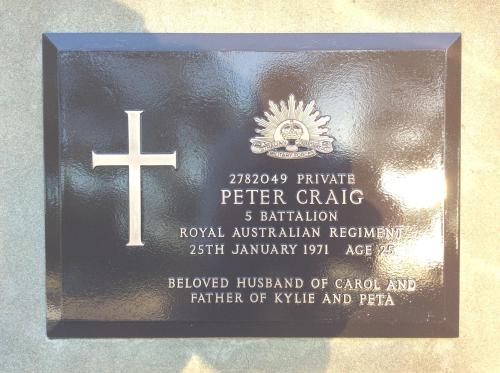

Another generation passed and there came yet more wars. These conflicts, too, are commemorated on another side of the obelisk. No. 2782049 Private Peter Craig was born in Coolamon on 12 June 1945, the son of Scottish settlers, Harry and Margaret Craig.[24] When he was 19, Peter was called up for service in the Australian Army under the National Service Scheme and was allocated as a rifleman to A Company of the 5th Battalion, Royal Australia Regiment, Holsworthy Barracks, where he duly arrived after initial training at the end of 1965.[25] 5RAR was warned that it would proceed to South Vietnam in 1966, and after a ticker-tape parade through Sydney, the majority of the unit (including Peter Craig) flew to Saigon in chartered Qantas airliners on 10 May 1966.

From there, the unit flew on transport aircraft to the Australian base at Nui Dat in the Phuoc Tuy province—its task to undertake counterinsurgency operations against the communist-backed Viet Cong rebels.

These were difficult and nerve-racking operations. Early in the conflict, the Australian infantry was tasked with securing the countryside around their main base. It took their whole tour of 12 months to accomplish. A walk in ‘the light green’, the less densely vegetated parts of the countryside, necessitated constant patrolling to search for and eliminate an elusive enemy.[29] It was hard, hot, and stressful work. Along with the physical strain, the tension was palpable. The knowledge that they could encounter Viet Cong fighters at any time galvanised the Australians. Every patrol was a dance with uncertainty; minutes stretched into hours, a slow march toward confrontation that could erupt in frantic bursts of violence at any moment. In mid-June 1966, an Australian newspaper hinted at the pressure. ‘Australian National Servicemen and other young soldiers with the Fifth Battalion have returned from their first combat patrols with a new outlook on the Vietnam War’[30], read the Canberra Times. A young Peter Craig gave his views. ‘You see a Viet Cong for a moment among the trees. You fire a few shots and, in many cases, you don't know if you have hit him,’ he told a reporter.[31]

Days followed days and became weeks and then months. The stress never quite went away. Peter Craig made it through his tour and travelled with the battalion when it returned to Australia in April 1967. He marched with his mates through the streets of Sydney on 16 May 1967; during the preceding year, 25 men had been killed in action or died of wounds, and a further 79 had been wounded. Like all combat veterans, Peter must have been irrevocably changed by his experiences in South Vietnam. However, we will never know to what extent. In 1971, as a young married husband and father, he fell ill. A son of Coolamon, he tragically passed away at only 25 years of age in Wagga Wagga, NSW, and is commemorated at the Wagga Wagga Lawn Cemetery.

In yet the passing of another generation, the great-grandchildren of the original Anzacs continue to offer their service to Australia. On 10 July 2007, a Tuesday, an Australian officer walked along a street in Baghdad’s International Zone. He was outside the US Embassy gates, and the sun was a copper orb in the early afternoon sky. It was beyond 50 degrees Celsius, and the sky was baked into the palest shades of blue; it was almost white. The heatwaves danced and the leaves wilted on the eucalypt trees around, all this despite the proximity of the nearby Tigris River. This time was at the height of the Coalition ‘surge’ in Iraq, and the US-led Multi-National Force had swelled across the nation to curb the insurgent brutality stemming from the deposition of Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime in 2003.

Every day, indescribable acts of violence occurred across the country as sectarian groups fought each other and tried to destroy the will of the Coalition presence. In the Iraqi capital and other large cities, the proliferation of improvised explosive devices, kidnappings, murder, and executions, all knew no bounds. In Baghdad, there was no power grid, it had been bombed out during the initial invasion; there was no potable water, and the Coalition worked desperately with the Iraqi people to find the peace. But it was hard going. At the height of the surge, an insurgent group rained daily indirect fire into Baghdad’s International Zone (IZ) seeking to destroy, maim, kill and weaken the resolve of their opponents. Sometimes it was two rockets, sometimes a salvo of five mortar rounds, every day there was a cumulative total of several dozen rounds indiscriminately fired into an area of perhaps five square miles: no one knew where or when it would fall, the Counter-Rocket, Artillery, Missile (C-RAM) systems designed to give early warning often went off after the rounds had landed.

On this Tuesday afternoon, as the Australian officer walked outside the US Embassy, insurgents selected this opportunity to mortar the IZ in its daily display of ‘hate’. The Australian—a descendant of a Gallipoli veteran— had been in Iraq as an embedded officer for only a few weeks. He saw and felt the first of the rounds fall. It was indiscriminate, and it was pure chance he was where he was and looking in the direction that he did. There were people scattered down the road ahead, not more than a hundred metres away, and the round crashed among them. There was a smash of dust and smoke, and a crack and concussive surge; he felt it in his belly. The road seemed to tilt, and the round exploded on top of, he thought, one individual in civilian attire. The shrapnel ripped and tore and screamed past the man with a sound like tearing canvas. A piece of it hit the wall beside his head and fell between the officer’s boots. A second round landed somewhere behind, but it seemed inconsequential, and the Australian officer picked up a shard of shrapnel from the first round and put it in his pocket. To this day, he knows not why.

When he looked back down the road, the Australian saw the figure on the ground and there hung a pall of dust. Several people were running towards the person. One was an Australian soldier, for the casualty had been hit outside the Australian Embassy, but to this day, the officer does not know who this other Australian was who rushed to assist someone under shellfire. He was, he is, a brave young digger. There were people everywhere, but there was nothing to be done, so the Australian officer walked back to the security of the US Embassy. He felt strange. The person who was struck was later identified as Captain María Inés Ortiz, an American nurse who was walking back from the gym. She was the first American nurse killed in action since the Vietnam War. She was born in the same year as the Australian officer, and she was stationed at the 28th Combat Support Hospital adjacent to the Australian Embassy in Baghdad’s IZ. Maria Ortiz left a family behind in the United States; there is no rhyme or reason why she died on this day except that she was walking where she was. From the time he learned of her name, the Australian has quietly commemorated her ever since, because ‘there but for the grace of God goes me’.[33]

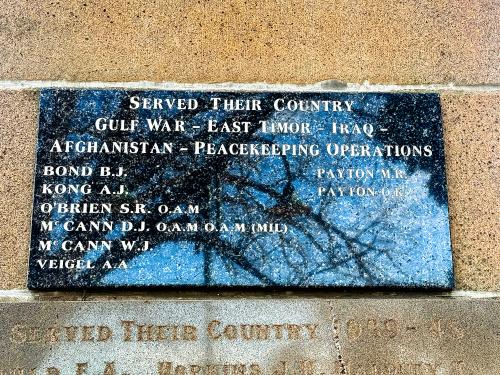

Petty Officer (writer) Stuart O’Brien was the administrative clerk assigned to assist the Australian personnel embedded to conduct the many functions of the Multi-National Force – Iraq. He is also a son of Coolamon and his name is on the monument in Cowabbie Street; pure, joyful coincidence. People come and go in one’s career, and the two men did not know each other, but the Australian officer served with O’Brien for some weeks before the latter rotated home. The officer knew O’Brien was efficient, straight up and down, and had a laconic sense of humour. The officer showed the shrapnel to him and described the incident. ‘Well, Sir,’ O’Brien said, ‘I have to raise an incident report on this.’ O’Brien took down the man’s story and checked it with him. When it was done, he looked at the officer closely: ‘Next time, lie down will you, Sir, or you will get knocked over.’ It is now 18 years past, and it is only a small story, but it leads us directly to this occasion. Later that day, O’Brien came to sit beside the officer in the mess for an evening meal, and he quietly asked: ‘Are you alright, mate?’

I have never forgotten this man who went on to render further magnificent service in the Royal Australian Navy (I doubt that Stuart O’Brien would recall me at all), but he is a tribute to the fine Coolamon community.

That is all there is for this wonderful structure, and it is more than enough; for indeed, the war memorial at Coolamon, like so many others across Australia, stands as a place of remembrance¾it urges us to reflect on our shared history, it instils in us a deep appreciation for the freedoms we enjoy today. If you are ever in Coolamon—it’s a beautiful town—I suggest that you stop to look at the memorial. Reflect on those who have served. The monument reminds me that the spirit of those who have served before lives on; their sacrifice inspires me to approach my life with gratitude, compassion, and a commitment to uphold the values of our nation. The changes have come and gone in a century. Some have been large, most not. In this time, the Coolamon obelisk has stood resolute in the sun and the rain, the frost, and the names have grown on its sides. Kelly, Dyce, Craig, O’Brien; the hundreds more listed on this cairn—they all matter. Australia and Coolamon remember them still.

1 Bruce Dellit, The Book of The Anzac Memorial New South Wales, Beacon Press, Sydney, 1934.

2 State Government of New South Wales: Environment and Heritage, ‘Riverina Bioregion’, [online] accessed at: https://www2.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/animals-and-plants/biodiversity/bioregions/bioregions-of-nsw/riverina

3 See: P. Cashin & C. McDermott, ‘Riding on the Sheep’s Back: Examining Australia’s Dependence on Wool Exports’, in The Economic Record, Vol. 78, No. 242, September 2002, pp. 249-263. In popular mythology the Australian economy ‘rode on the sheep’s back’ it was so dependent on the wool industry. Such was the contribution of wool that in 1938 an image of the Merino sheep was placed on the Australian shilling. It remained there until 1966.

4 A.W. Reed, Placenames of New South Wales: Their Origins and Meanings, A.H. & A.W. Reed Publishers, Sydney, 1969, p. 42.

5 Reed, p. 42.

6 State Government of NSW: Common War Memorials in New South Wales, [online] accessed at: https://www.veterans.nsw.gov.au/assets/War-memorial-survey/2.-Common-War-Memorials-in-NSW-accessible.pdf

7 Peter Dennis, Geoffrey Grey, Ewan Morris and Robin Prior, The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1995, p. 259.

8 C.E.W. Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol. II The Story of Anzac from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation (hereafter OH Vol. II), Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1933, p. 566.

9 National Archives of Australia, Australian Imperial Force series number B2455, Kelly, William, SERN: 1577, POB: Argyle Scotland, POE: Liverpool NSW, NOK: Father Patrick Kelly, Coolamon NSW.

10 Bean, OH Vol. II, p. 537.

11 Virtual War Memorial of Australia, William Kelly DCM, [online] accessed at: https://vwma.org.au/explore/people/319015

12 Bean, OH Vol. II, p. 537

13 National Archives of Australia, Australian Imperial Force series number B2455, Kelly, William, SERN: 1577, POB: Argyle Scotland, POE: Liverpool NSW, NOK: Father Patrick Kelly, Coolamon NSW.

14 The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Coy. Delta acted as a Hospital Ship from 14 Jan 1914 to 19 Mar 1918. Staffed by 6 Medical Officers, 12 Nurses and 45 other staff it was fitted with 287 cots and 210 berths. In 1915 it was used as a Hospital Ship for the Dardanelles, arriving a couple of days after the landing at Cape Helles and remaining active there until at least November 1915., [online] accessed at: HMHS Delta - Our Contributionhttps://vwma.org.au/explore/people/319015

15 A. Stephens, The Australian Centenary History of Defence, Volume II, The Royal Australian Air Force, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2001, PP. 60,64-66.

16 National Archives of Australia, Royal Australian Air Force series number A9301 Dyce, Kenneth Douglas, Service Number: 412411, of Coolamon NSW, [online] accessed at: https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ListingReports/ItemsListing.aspx

17 National Archives of Australia, Royal Australian Air Force series number A9301 Dyce, Kenneth Douglas, Service Number: 412411, of Coolamon NSW.

18 National Archives of Australia, Royal Australian Air Force series number A705, 16610/66 Dyce, Kenneth Douglas, Service Number: 412411, killed in the flying battle over Holland, 24 May 1943.

19 D. O’Malley, ‘A Terrifying Beauty - The Art of Piotr Forkasiewicz’, Vintage Wings of Canada, [online] accessed at: https://www.vintagewings.ca/stories/a-terrifying-beauty

20 National Archives of Australia, Royal Australian Air Force series number A9301 Dyce, Kenneth Douglas, Service Number: 412411, of Coolamon NSW.

21 Letter published in the Coolamon Ganmain Review, 14 May 1943, p. 2, [online] accessed at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/282490707

22 The National Archives, Kew, AIR 27/1908/9, Summary of events 460 SQN RAAF, 1-31 May 1943, [online] accessed at: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D8438877 Lancaster W4984 was returning from a raid on Dortmund when it was shot down by Oberleutnant August Geiger flying a Messerschmitt-110 night fighter from the Twenthe Airbase in the eastern Netherlands.

24 Courtesy of Ms Lyn Hamilton, Private Peter Craig, Find a Grave Memorial, [online] accessed at: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/37583651/peter-craig

25 Virtual War Memorial, Service pertaining to No. 2782049 Private Peter Craig, [online] accessed at: https://vwma.org.au/explore/people/654282

26 5th Battalion RAR Association, The Battalion Prepares for War, [online] accessed at: https://5rar.asn.au/5rar-formation-and-preparation-for-war/

27 5th Battalion RAR Association, Nui Dat, [online] accessed at: https://5rar.asn.au/arial-view-1atf/

28 Michael Coleridge, AWM COL/67/0112/VN, black and white image, 5RAR patrol in the Phuoc Tuy province 1966-7, [online] available at:

29 Ian MacNeil, To Long Tan: The Australian Army and the Vietnam War 1950-66, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1993, pp. 246-247.

30 Canberra Times, 8 June 1966, p. 16. [online] accessed at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/136926368

31 Canberra Times, 8 June 1966, p. 16. [online] accessed at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/136926368

32 Courtesy of Ms Lyn Hamilton, Private Peter Craig, Find a Grave Memorial, [online] accessed at: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/37583651/peter-craig

33 That was I. That was me. I was the Australian officer, and there was a son of Coolamon close by.

34 Courtesy of Elizabeth Reed, Captain María Inés Ortiz, Find a Grave Memorial, [online] accessed at: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/20422001/maria_ines-ortiz

Technical Mastery

Social Mastery

This Hallowed Place © 2025 by . This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.