Editor's Note: This article was first published by Small Wars Journal. It has been edited for an Australian audience.

On 30 March 1972, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) invaded South Vietnam and the Easter Offensive of 1972 began, flouting their 1968 promise to ‘respect the DMZ’.

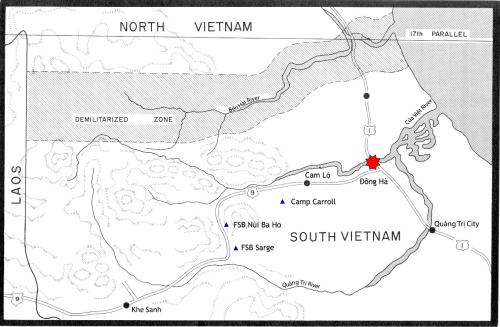

Though seldom acknowledged or known by many, the priority objective of North Vietnam’s invasion was northern South Vietnam. Eventually, six NVA divisions, two tank regiments, and three-four independent infantry regiments would strike through the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and Laos catching United States and South Vietnamese command elements completely dumbfounded and slow to respond. (Further, an entirely new division was also created in southern I Corps, as well.) US and Republic of Vietnam (RVN) commands had forecasted that the NVA would strike during Tết[1] 1972 (15 February that year), but nothing happened. As time continued with no signs that it was soon to begin, the atmosphere grew more relaxed, though infiltration totals well exceeded that of the Tết Offensive of 1968, the build-up was bound to erupt sometime.

As Easter neared, many generals and senior officials decided to take a little vacation. The US Ambassador to South Vietnam (Ellsworth Bunker) went to Nepal, the commander (General Abrams) of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) visited his family in Thailand, the MACV J-2 (Major General William Potts) went on R&R to Hawaii, and Colonel Metcalf (commanding Team 155 advising the Army of the Republic of Vietnam 3rd Division) was leaving for the Philippines to visit his family. Even the Secretary of Defense, Melvin Laird, was preparing to play golf in Puerto Rico. Some Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) generals have written that they had sent out a country-wide alert during this time, though no one seems to have received it (neither South Vietnamese nor Americans). This included a US Army intelligence unit running agents (HUMINT) throughout I Corps.

571st Military Intelligence (MI) Detachment’s agents had warned of the delay at Tết, but knew it was soon to erupt. As the Easter Offensive approached, the unit published the first Intelligence Summary in its (and its parent organisation, the 525 MI Group) history in Vietnam.

The invasion began at daybreak on 30 March 1972, when Fire Support Base (FSB) Sarge (with Major Walt Boomer, United States Marine Corps) and nearby FSB Nui Ba Ho (with Captain Ray Smith, US Marine Corps) became subjected to an intense artillery attack. Sarge has the sad distinction of also being the place where the first two Americans were KIA. Both were US Army soldiers assigned to the 407th Radio Research Detachment. Bruce Crosby and Gary Westcott were operating their SIGINT equipment atop Sarge when a 122mm rocket went into their small bunker and exploded.

This was to be a day of firsts as long-range artillery, tanks, and infantry fought in limited combined arms engagements using armoured personnel carriers and trucks under a surface-to-air missile (SAM) and anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) air defence umbrella positioned above, in, and under the DMZ, using roads created months before. A third NVA division (the 324B) had come in via Laos earlier in March and had been keeping the 1st ARVN Division busy west of Huế , preventing any thought of it assisting 3rd ARVN in Quảng Trị.

As the 304th NVA Infantry Division and the attached 203rd Armored Regiment entered South Vietnam from Laos and the western DMZ, the 308th NVA Infantry Division with the 202nd Armored Regiment overwhelmed the fire support bases below the DMZ and headed for the Đông Hà Bridge to continue their southerly advance using the major north-south roadway, QL-1.

Reminiscent of the Battle of the Bulge, weather had moved in with heavy and low overcast clouds making air support spotty, at best. Forward Air Control (FAC) aircraft were forced to play peek-a-boo to catch glimpses of enemy activity, always risking AAA and SAM responses. Most tactical aircraft were prevented from flying that low, under the cloud banks.

* * *

What came a few days later is also an epic tale of valour and tenacity, which perhaps has never clearly been understood before.

Easter Sunday, 02 April 1972, opened with a South Vietnamese Marine Corps (VNMC) battalion holding the south bank of the Cửa Việt river at Đông Hà. The bridge was well-built by US Marines and was situated next to a railroad bridge to its west. The 3rd VNMC Battalion, Brigade 258 was led by Major Le Ba Binh, with USMC Captain John Ripley as his covan[2].

The newly activated ARVN tank unit, the 20th Tank Squadron (with Major Smock as its adviser) had also been dispatched to the bridge area with orders to hold it against NVA forces that were expected.

As the day progressed, it became clear that the bridge had to be blown to prevent the NVA from crossing it and continuing to their probable objective, Quảng Trị City. Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Turley, USMC, had taken over the operations section of Team 155, and had ordered Ripley to bring the bridge down, though he was aware that the ARVN wanted it to remain standing for their implausible counter-attack plans. Captain Ripley was trained in ‘blowing things up’.

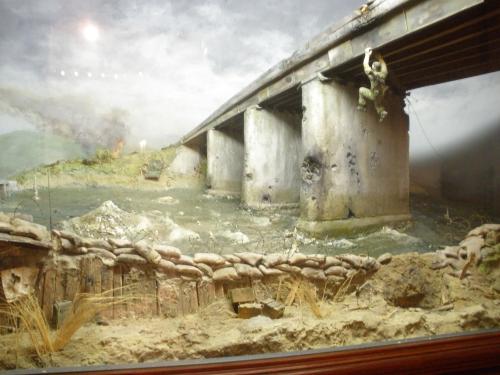

General Abrams was briefed during the 03 April 1972 Commander US Military Assistance Command Vietnam (COMUSMACV ) Update that, ‘Re the Đông Hà bridge, this was blown by a US advisor, a captain with 400 pounds of TNT that he personally put under the bridge and wired it up and blew it – uh, while waiting for clearance.’ [Laughter] ‘He was being shot at by tanks from the north side of the river at the time.’[3]

US naval gunfire support was often provided by destroyers on the gunline offshore from the DMZ, solely by the USS Buchanan (DDG-14)[4] this day—the destroyers Waddell, Hamner, Strauss, and Anderson weren’t in the immediate area when the Đông Hà bridge was dropped. The Buchanan would have probably received intelligence from the Naval Intelligence Liaison Office in Đà Nẵng (along with the Navy SEALs), who likely also provided intelligence to the Commander, Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC[5]) in Hawaii with our (571st MI Detachment) timely tactical situational reporting that the MACV commander, General Creighton Abrams, his J-2, and FRAC (in charge of all advisers in I Corps) were also receiving. The destroyers were not held under Operations Control (OPCON) to MACV or I Corps and, therefore, reported directly to CINCPAC, Admiral McCain, who in turn relayed information from Hawaii back to MACV in Saigon.

LCDR Gil Hansen was Executive Officer (XO) of the USS Buchanan (DDG-14) when the Easter Offensive began. He has shared his recollections with this author[6], stating: ‘As far as the three versions of the Đông Hà bridge is concerned, I can confirm it was John Ripley who blew that bridge. There were no aircraft in the area. I was on the bridge of Buchanan almost the whole time. We actually took those tanks on the bridge under direct fire. We could see them visually. I remember one of those tanks going forward, then going backward until we nailed him. In the meantime, a spotter was directing our fire while John Ripley was going hand over hand under the bridge dodging sniper fire while laying the explosives under the bridge. If there were any ARVN troops around, I would have heard about it. As I remember, there weren't even any Vietnamese Marines around that he had been “advising”—only John and a US Army Major (I think) helping him by passing the charges over a barbed-wire fence to him as he returned to lay another load of explosives. He received the Navy Cross for that action—well deserved. You are probably aware that at the entrance to Memorial Hall in Bancroft Hall at US Naval Academy, there is a diorama of John blowing the bridge.’ [7]

According to Dean M. Myers, an ETR (Radar Tech) aboard the Buchanan during the Easter Offensive, ‘The CO James Thearle passed away several years ago. I do not know anything about Commodore “Choo Choo” Johnson (He was a Navy SEAL, not too many Navy Captains wore the Trident in ’72). He worked to keep us in the middle of all action he could. That is why we were in so many hot spots.’[8] And indeed they were being credited with knocking out four tanks.

A fortunate coincidence brought Captain Ripley and Major Smock to the Đông Hà bridge and the USS Buchanan to the gunline off the DMZ. It undoubtedly had more of an effect than just preventing an NVA division from crossing the Đông Hà Bridge. It ensured that the tide of battle would eventually turn in favour of the South Vietnamese forces.

Consider the following…

The 304th NVA Division and the 203rd Armored Regiment’s entry into South Vietnam from the western DMZ and Laos went without any apparent problems. The 308th NVA Division and the 202nd Armored Regiment were prevented from crossing the Miếu Giàng/Cửa Việt River via the Đông Hà bridge and apparently also by fording—their double envelopment plans fell through. The 308/202 were forced then to go miles westward to the Cam Lộ bridge, where other units of the 304/203 were undoubtedly crossing, too. This movement was seen and reacted to by the only artillery available in the area—two 5”/54 calibre Mark 42 guns of the USS Buchanan. It was the only artillery available in all Quảng Trị Province because the entire 56th ARVN Regiment of the 3rd ARVN Division was in the process of surrendering Camp Carroll with its 22 unspiked artillery pieces (including four 175mm guns) to the 24th NVA Regiment of the 304th NVA Division.

The 304/203 were able to begin and conduct their part of the planned blitzkrieg with their successful envelopment of the ARVN western defensive line and continued their operations (usually as regiments) against the firebases and Camp Carroll. While some strategists may point out that there was an absence of tactical airpower necessary in a blitzkrieg, bad weather effectively nixed this requirement (especially since allied tactical airpower faced the same difficulty with a much greater disadvantage). Was this weather part of the North Vietnam’s strategic calculations (as in the Allied invasion in Normandy or by the Germans at Bastogne in WWII) or was it sheer coincidence?

The 308/202 delay was costly. These units had to turn west and then cross at Cam Lộ (using the bridge that wasn’t blown for over a week more), ford the river in their APCs, or (as only mentioned in the FRAC Command History 1972-1973) cross by sampan! When the weather began to clear, US tactical aircraft that had already returned to Vietnam pounced on NVA targets, as more clarity of the ground situation became known. The 571st MI Detachment’s reporting was finally accepted as factual intelligence, proving the baseline for NVA movements and locations.

One can easily surmise that if the Đông Hà bridge hadn’t been brought down by Ripley and Smock, and if the USS Buchanan hadn’t been providing gunfire support, that Quảng Trị City would have quickly fallen as 3rd ARVN’s troops and leadership proved to be no match against the NVA.

With the 324B NVA Division and two independent NVA regiments tying up the 1st ARVN Division in Huế, they might have been able to have rapidly assaulted the Imperial City from the north as well.

The USS Buchanan received the Meritorious Unit Commendation for this period. Captain John Ripley was awarded the Navy Cross.

Many thought then that Ripley deserved the Congressional Medal of Honor. Many continue to think so today. This was certainly also a joint effort by many, all worthy of special recognition, especially when you consider that it undoubtedly saved many more American and South Vietnamese lives by upsetting NVA plans for a rapid conquest of at least Quảng Trị City and possibly an assault on Huế.

1Tết in this instance refers to the Vietnamese new year celebrations of 1972, not the Tết Offensive of 1968. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%E1%BA%BFt

2 Trusted Advisor

3 Lewis Sorely, Vietnam Chronicles: The Abrams Tapes 1968-1972, Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2004, 807

5 Commander-in-Chief Pacific

6 ‘Breaking the Chain’, Walter Robert (Bob) Baker, Chapter 13 ‘The Bridge at Dong Ha’

7 Email with Gil Hansen, Executive Officer of the USS Buchanan, DDG -14, during the Easter Offensive of 1972, March 15, 2016 (hereafter cited as Hansen, USS Buchanan).

8 Dean M. Myers, an ETR (Radar Tech) aboard the Buchanan during the Easter Offensive, March 11, 2016, email to author.

Defence Mastery

Social Mastery

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.