Introduction

The Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) is a step-by-step instruction booklet devoid of effective tools. The manual describes all the steps required to build a plan yet lacks sufficient tangible tools, processes, or models for planners to select from. Its linear nature and spoonfed inputs and outputs lead to a paint-by-numbers art project whose only efficiency is the similarity to other Western planning doctrines. The JMAP preaches iterative and non-prescriptive planning yet arranges its outputs so that this cannot occur. The JMAP struggles to gain efficiencies across staff functions, namely plans and current operations, resulting in a process that contradicts the principles of war and the principles of planning.

This essay will briefly highlight the immense similarity the JMAP has with other allied planning doctrines and offer alternate planning frameworks as potential amendments to the established military planning dogma. It will argue that the JMAP is too long, too linear, too prescriptive and lacks the tools that planners need to create plans effectively. It will highlight the divergence in the JMAP and its underlying principles. And, finally, it will conclude by offering amendments to the current JMAP doctrine to make it more applicable to the Australian Defence Force.

The JMAP is the ADF’s key planning doctrine for military operations.[1] The JMAP was initially born from the Army’s Military Appreciation Process in 1996, whose roots can be traced to earlier British processes and American Doctrine.[2] Since then, the generations of ADF planning doctrine have evolved into the overly descriptive, linear, and output-focused manual we see today. As the character of war has become more complex and technical, the ADF must swiftly adapt its planning processes to achieve the sufficient Tempo and Decision Superiority needed to defeat its adversaries. Unfortunately, this complexity has made the planning process more complex rather than refined and purposeful. Many staff become annoyed with the length of the planning publications, the confusing outputs needed to advance down the planning pathway, and the lack of freedom to truly think. Whilst the ADF’s JMAP readily aligns with many other allied processes, this so-called strength has meant slow adaptation in doctrine and a focus on integration with a coalition rather than fighting a thinking and moving enemy.

What alternatives can the ADF adopt? What other processes can be learned from? How can these be applied to the ADF? Firstly, we must review the Western approach to planning.

Comparisons and Alternatives

NATO and Western Doctrine

The JMAP cannot effectively be compared to NATO or Western planning doctrines. No revolutionary differences can be found when comparing the JMAP to other Western military planning documents; they are all too similar. The JMAP, the United States Joint Publication 5-0 Planning, and the UK Allied Joint Publication-5 Planning of Operations are all oranges.[3] The steps of the JMAP are Scoping and Framing, Mission Analysis, Course of Action (COA) Development, COA Analysis and Decision and CONOP Development.[4] The Steps in US Joint Planning are Planning Initiation, Mission Analysis, COA Development, COA Analysis and Wargaming, COA Comparison, COA Approval and Plan/Order Development.[5] The steps of the UK NATO Planning are Initiation, Mission Analysis, COA Development, COA Analysis, COA Validation and Comparison, Commander’s Decision and Plan Development.[6] Across all Western military planning doctrines, the similarities are nearly identical. Looking internally, even the Army planning doctrine LWD 5-1-4, the Military Appreciation Process is incredibly like the JMAP, with the only change in steps being the replacement of Scoping and Framing with Preliminary Analysis.[7] For what the JMAP gains in interoperability with allies, it loses in creativity, uniqueness, and novel solutions. To quote Eisenhower, ‘No one is thinking if we are all thinking the same’.[8] The ADF must break this dogma and forge planners who can deliver results rather than those who can seamlessly integrate into a coalition headquarters. As NATO and Western planning doctrines are largely identical, only by looking broader can we identify the apples (differing points of view) that can inform appropriate change. Lessons from industry and computer programming provide alternate processes and viewpoints.

Agile Project Management and Non-Linear planning

Agile Project Management and Non-linear planning offer valid comparisons and address the flaws of JMAP. Agile Project Management is a project management style, meaning planning and execution, from industry, namely the technology sector.[9] It seeks the efficient balance of planning and execution simultaneously and understands the changing and complex nature of planning rather than the singular and fixed end states and Centres of Gravity (COG) found in military doctrine.[10] Agile Management emphasises continual iteration and a bias for action.[11] Like war, managing projects is not a static or singular endeavour; the enemy has a say, the environment changes, and future goals are altered. Agile Project Management factors these concerns into the outset of planning. In complement to this, Non-Linear Planning or Partial-Order Planning, often seen in computer programming, seeks elegant and efficient use of time and effort by capitalising on concurrency and simultaneous actions.[12] Non-Linear Planning may still require the initiation of certain components to commence the work of other sub-steps but does not restrict the program’s potential by waiting for chronological outputs to be met.[13] This partial-order planning builds efficiency and speed in the planning process and allows actual divergence and convergence in thinking. The concepts and combination of Agile Management and Non-Linear Planning offer two key comparisons against the JMAP that would enable true critical thinking, efficiency in planning, and remove the linear restrictions of the current process. These two concepts will be used to make recommendations in this paper and provide potential amendments to existing processes. By adopting lessons from Agile Management and Non-Linear planning, the JMAP could reduce its now gargantuan size.

MB2 Too Long, too Linear and too Prescriptive

Too Long

The formal planning process has grown significantly in length since its adoption in 1996.[14] One can only speculate why the JMAP is as long as it is. The increased complexity of warfare, the need to cater to the most basic of minds, or because other nations are doing it may be worthy answers. Regardless, 228 pages of step-by-step outputs are too much.[15] This undue length is countered by Army doctrine through the Individual Military Appreciation Process and the Combat Military Appreciation Process.[16] These processes show that plans can still be generated with much shorter and simpler doctrines. The UK’s Combat Estimate, or ‘Seven Questions’, is another example of a more straightforward process that aims to achieve the same result.[17] The length of the current doctrine is a significant barrier to many new planners who may not have time to digest 228 prescriptive outputs. A shorter doctrinal volume will make the JMAP accessible to far more users and be further enhanced by removing single-path linearity.

Too Linear

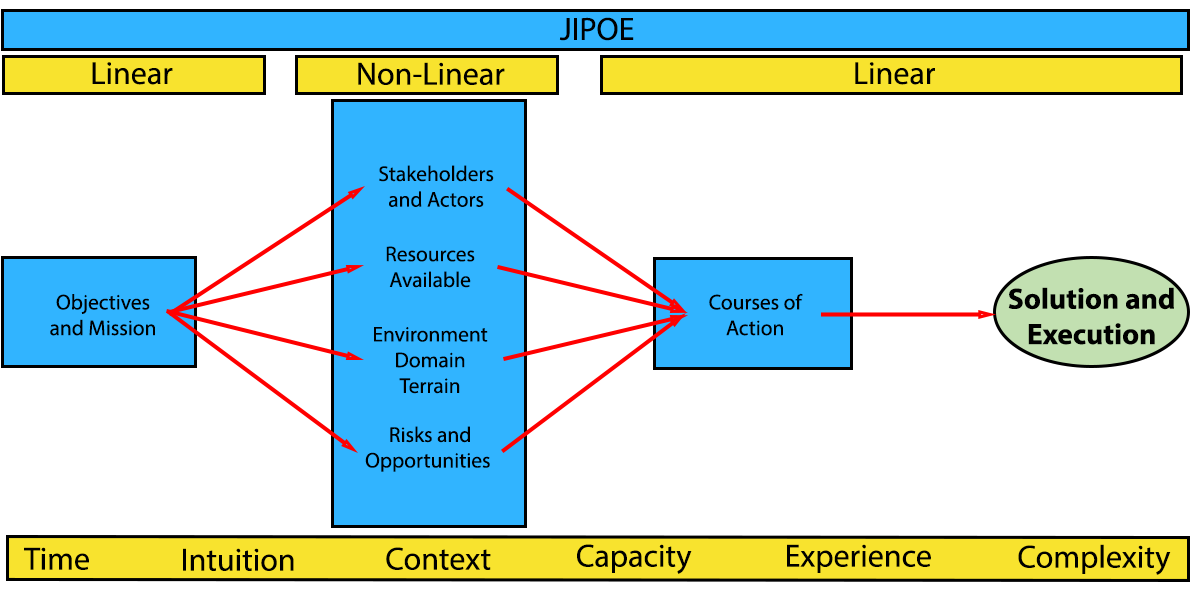

The JMAP is a linear and output-driven conquest that hopefully spits out a plan at the end. Para 1.3 of the JMAP lists the steps required in a specific order.[18] Doctrine from other nations also does this. Para 4.1 of the UK NATO Joint Planning Process explicitly states ‘The sequence of planning activities’.[19] Only by completing the first step can you move to the second. A perfect example of this in the JMAP is Decisive Points (DPs). ADF-P-5 Planning designates DPs as a key milestone derived by combining a target to an effect at a given time and place.[20] These are nicely colour-coded and described like an equation. The JMAP supports this by adding that DPs are derived from essential tasks and critical factors along with the above arithmetic.[21] The concept of DPs perfectly outlines the linear and output-focused formula of the JMAP. Only by completing the Joint Intelligence Preparation of the Operational Environment (JIPOE) can you derive stakeholder critical factors; only by completing Scoping and Framing can you derive a time and place to insert effects, and only by completing the earlier steps of Mission Analysis can you derive friendly critical factors and essential tasks. As mentioned above, Non-Linear Planning used in programming and coding may provide a potential solution. An initiating step puts in motion multiple steps that are completed at once. Parts of these steps can support other steps once complete. They are not tied to a linear output but rather a seed that branches into multiple processes that eventually come together to create the tree (the end product). The chapters in the JMAP that cover the major steps must not be presented in any particular order nor describe the required outputs or preconditions to commence the next action. All steps of the JMAP must be related but not tied to one another. The author suggests Figure 1 as an example of how this nonlinearity may apply to the current JMAP. In the current process, step X must be completed before step Y can begin. This restricts thinking, slows the JMAP immensely and gives the staff a single output focus rather than revisiting, reimagining and critically thinking.

Figure 1.

A planning approach like Figure 1 would see a single initiating step that unleashes multiple follow-up steps of concurrent and time-efficient planning. Under this model, both Linear and Non-Linear phases would effectively diverge and converge the planning staff and remove another of the JMAP’s weaknesses, its prescriptiveness.

Too Prescriptive

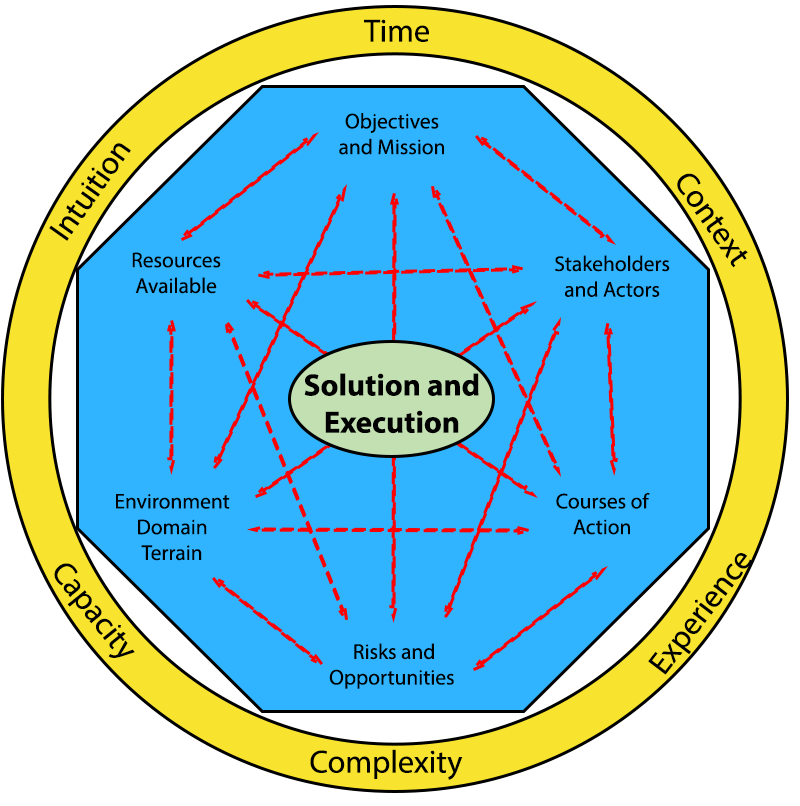

The JMAP statements of cyclical and iterative planning are merely lip service. Para 1.33 of the JMAP speaks of breaking the prescribed linear process.[22] Other ADF doctrine reinforces this; LWD 5.1.4 MAP (the JMAP predecessor) details the MAP as a command-driven and iterative process.[23] The same theme can be seen looking wider at other allied doctrines. The US ADP 5-0 states, ‘The Army Design Methodology is Iterative in Nature’.[24] These statements are inserted to make the JMAP sound flexible and non-rigid, yet they continue to describe steps that must be completed one at a time before moving to the next output-driven stage. Scoping and Framing is the only part of the JMAP where dedicated revisiting of planning is suggested. However, it is not a dedicated sub-step.[25] Para 1.2 of the JMAP states that ‘it is not supposed to be a formulaic checklist’, yet all steps of the JMAP are numbered and placed in a semi-logical order.[26] Para 3.1 rather prescriptively states that ‘Mission Analysis is the second step in the JMAP’.[27] It also outlines the sub-steps required to be met in order. This prescriptive nature is a detriment to planning and thinking as later steps may significantly alter early assumptions. A friendly COA may have a different friendly COG than initially planned in Mission Analysis. Developing a Line of Operation (LOO) Diagram at the end of Mission Analysis will significantly shape one’s thinking when creating a COA-specific LOO in Step Three. Staff may also miss important lessons and analyses if they discard suitable COAs before the War Game at Step Four. If time permits, valuable lessons can be learned from taking unique COAs to the War Gaming table. The author suggests Figure 2 as an example of how to remove the prescriptive nature of the JMAP altogether and achieve true iterative and unbounded planning. This structure allows for efficiency and speed of planning.

Figure 2.

In Figure 2, the planner may start wherever they please or where they are best placed to analyse and plan. A planner may wish to begin with resources before moving onto courses of action and then on to a split planning group of risks and objectives. Using this non-prescriptive planning process would build a significant amount of efficiency and speed.

Building Efficiency and Tools

Efficiency and Speed

Due to the linear nature of the JMAP, efficiency and speed are lost. The principles of war are a sound set of guiding considerations when conducting war and, therefore, planning for it. Yet, the JMAP design contradicts the principles of Surprise and Flexibility with its drawn-out process.[28] The tenets of Manoeuvre Warfare also describe the need for Tempo, Simultaneity and Surprise, which is significantly hampered under the current planning process.[29] Additionally, the characteristics of ADF warfare describe Decision Superiority as a key theme.[30] Meaning speed of decision and building tempo. Lastly, Annex 2B of the ADF-P-5 Planning describes timeliness as a key planning principle.[31] If the ADF is to truly build flexibility, tempo, surprise, and timeliness into planning, then efficiencies must be built into the planning process. Under the present NATO staff model, the plans cell (J5) conducts linear planning; this oft-halfway completed plan is handed to the future operations cell (J35) for finalisation before being passed to the current operations cell (J3) for execution.[32] To meet the planning principles described above and to build speed into planning and execution, the ADF must seek efficiency and speed by building agile planning teams. The aforementioned Agile Project Management processes may be the answer to addressing this. Under the Agile Project Management model, planning is simultaneously combined with execution, allowing action regardless of the planning step. This form of project management understands the changing nature of planning and execution; it accounts for real-world issues and changing end states. Jim Storr writes that the Plans function in headquarters is flawed and has become a pursuit in its own right and, therefore, not linked to Operations.[33] The slow, linear and stovepiped model the ADF uses is not fit for the speed of the contemporary environment and only accounts for static, singular end states. The ADF planning doctrine should not be a slave to the staff system. Planning should not stovepipe segments of the plan to specific cells, and the artificial gates between Plans and Operations should be broken down into one cohesive team. For these agile planning teams to succeed, they need tools to complete the job.

Tools for the Planner

Finally, to release the true potential of the JMAP, the builder must be provided with the tools to carry out the task. Mental models are helpful tools, although often incomplete and unscientific.[34] Another way of thinking about these tools is the following quote by George Box: ‘All mental models are wrong; some are useful.’[35] This statement succinctly articulates that select tools for select problems are indeed helpful. The JMAP, however, offers but a small handful of tools to the planner.[36] These are mostly examples rather than dedicated planning tools, such as synch matrices and a COG diagram. The word ‘bias’ is mentioned in the JMAP only four times.[37] Of these four times, only one instance is focused on the biases of the planning group.[38] The word ‘thinking’ is mentioned 36 times.[39] The vast majority of these mentions are associated with the term ‘critical thinking’. Robertson writes that there is far more than one type of thinking and that ‘Differing problems require different types of thinking’.[40] Planners and staff must be exposed to all types. Far more needs to be provided to the planner, including types of thinking, types of biases, design theory, tools for thinking, models for deriving deductions, examples and matrices. The small pool of examples and mention of the term critical thinking do not support planning. A range of tools and examples to build creative solutions should be written into the annexes of the JMAP. The planner can then select tools that they believe are required to develop the plan. For example, a planner may disregard COG analysis as the adversary may be far too complex to distil into a single sentence, and disregard parts of Scoping and Framing as the situation is obviously quite simple. They may also develop 10 unique COAs using numerous differing tools and styles of thinking. These may include a SWOT analysis, mind maps, the Eisenhower Matrix, ways matrices, backward planning, rich pictures or even narrative and storytelling. Finally, the planner may spend most of their time meticulously wargaming all 10 scenarios and weeding out the failures whilst using lateral thinking, red teaming, risk analysis, actor relations and reductionist thinking. Effective plans can be built only by empowering the planner to select the tools for the job. Table 1 suggests a non-exhaustive list of planning tools, types of thinking and mental models that planners may select from when planning.

Military Planning Process Steps (Must consider) | The potential list of tools/examples (The tool bag) |

|---|---|

Objectives and Mission | Commanders Intent statements. Mission statements. Task List. Eisenhower Matrix.[41] Sung Matrix.[42] Operational Timelines. COG analysis. SMART Goals. LOO Diagram. Johari Window.[43] Reductionist thinking. CARVER. |

Stakeholders and Actors | PEMESII-PT, ACOPSE, DIME, STEEPLEM. Problem Frame. Actor analysis and relations. Define the AO. Determine Stakeholder COA. Red teaming. SWOT Analysis.[44] COG analysis. Trends Analysis. Perspectives thinking: first position, second position, third position, etc.[45] Johari Window.[46] Small world phenomenon (6 degrees of separation) model.[47] Black Swan planning.[48] Narratives/Story.[49] |

Courses of Action | Ways Matrix. COA Sketches. Rich Pictures. COA Statements. COA timelines. Crazy Ivans. Resource allocation. Counter Statements. Use of Domain, Task or War principles. Wargaming. Brainstorming. Mind mapping.[50] Futures Analysis. Backwards planning / Reverse Engineering.[51] Role-playing model.[52] Result optimisation models. Narrative/Story |

Risks and Opportunities | SWOT Analysis.[53] Inherent Residual, Residual Risk, Risk Guidance. Treat, Transfer, Tolerate, and Terminate Criteria. Risk Matrix, Risk Relation diagram. CARVER. |

Environment, Domain and Terrain | MCOO. Domain Principles. Key Terrain. Decisive Terrain. PEMESII-PT, ASCOPE. OCOKA. |

Resources Available | ORBATs. C2 models. Capabilities statements. Resource Calculations. Time, speed, distance. Lists, quantities, tables. |

Conclusion

This essay has attempted to change the JMAP for the better. It has highlighted the sheep-like similarity the JMAP has with all other Western military planning doctrines. It has provided alternate processes which may supplement or adapt the current planning process. Non-Linear programming highlights potential efficiency gains and tempo in planning. Agile Project Management principles cater for execution whilst planning and factor in the evolving nature of the situation. It has shown the excessive length of the current planning doctrine and the linear and output-driven steps required to advance to the next stage. Input ‘A’ plus input ‘B’ does not necessarily equal output ‘C’. The evolving character of war means greater complexity and greater confusion. The ADF’s JMAP is, unfortunately, adopting both these themes in stark hypocrisy to its principles. By adhering to the principles outlined in the planning doctrine, the JMAP can be much shorter and begin to generate real Economy of Effort, Tempo, Timeliness and, ultimately, Decision Superiority for a military commander. Lastly, the JMAP has no tools. Examples, models, types of thinking and sets of applicable principles are few and far between. The JMAP must offer the staff tools such as mind-mapping literature, lessons on narrative and storytelling, simple methods such as ways matrices[54] or guidance on developing rich pictures. These tools give junior planners something to use in lieu of experience and allow the seasoned planner to omit tools not required for the scenario.

The following recommendations are made:

- The ‘steps’ of the JMAP become non-prescriptive and only offer a broad overview of the intent and aim of each step, reducing them from hundreds of pages to a dozen or so.

- The ‘steps’ of the JMAP become non-linear or semi-linear to build efficiency in the planning staff and bypass steps not essential to the given scenario.

- The annex/es of the JMAP become/s the vast majority of the publication’s content and filled with tools and supplementary information. The planner or staff can then select the tools they need to develop an effective military plan.

- The first chapter of the JMAP be dedicated to types of thinking, biases, an introduction to complex and complicated problems, and an explanation of the psychology of planning.

The spoonfed and output-orientated planning process used in the ADF is not fit for purpose and is not suited to the dynamic and complex scenarios in which it will be applied. Its applicability for the ADF is dwindling as war becomes more complex. In short, the JMAP must be a simple and non-linear framework for which the planner can select the tools to build the plan. Only by doing this can true thinking occur and creative plans be developed.

ADF Integrated Doctrine: 0 Series: Command: Headquarters and Staff Functions. Ed 1. Canberra: Directorate of Information, Graphics and eResources, 2022.

ADF Philosophical Doctrine - 3 Series: Campaigns and Operations. Ed 2 AL2. Canberra: Directorate of Information, Graphics and eResources, 2021.

ADF Philosophical Doctrine 5 Series Planning. Edition 1st. Canberra: Directorate of Information, Graphics and eResources, 2021.

Allied Joint Publication-5 Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations. Edition A Version 2. NATO Standards Office (NSO), 2019.

Army Doctrine Publication 5-0 The Operations Process. Headquarters, Department Of The Army, 2019.

Army Leadership Doctrine AC72029. The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst: Centre for Army Leadership, nd.

Australian Defence Force Publication 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process. Ed 2. Canberra: Joint Doctrine Directorate, 2019.

Barrett, Anthony, and Daniel S. Weld. ‘Partial-Order Planning: Evaluating Possible Efficiency Gains’. Artificial Intelligence 67, no. 1 (1 May 1994): pp 71–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-3702(94)90012-4

Bratterud, Hannah, Mac Burgess, Brittany Terese Fasy, David L. Millman, Troy Oster, and Eunyoung (Christine) Sung. ‘The Sung Diagram: Revitalizing the Eisenhower Matrix’. In Diagrammatic Representation and Inference, edited by Ahti-Veikko Pietarinen, Peter Chapman, Leonie Bosveld-de Smet, Valeria Giardino, James Corter, and Sven Linker, pp 498–502. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54249-8_43

Easley, David, and Jon Kleinberg. ‘The Small-World Phenomenon’. In Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Edwards, Sarah, and Nick Cooper. ‘Mind Mapping as a Teaching Resource’. The Clinical Teacher 7, no. 4 (2010): 236–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2010.00395.x

Gentner, Dedre, and Albert L Stevens. Mental Models. London, UK: Taylor & Francis Group, 1983. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/deakin/detail.action?docID=1596442

Gurl, Emet. ‘Swot Analysis: A Theoretical Review’, 11 August 2017. http://hdl.handle.net/10673/792

Hass, Kathleen B. ‘The Blending of Traditional and Agile Project Management’, 2007.

Innes, Judith E, and David E Booher. ‘Consensus Building as Role Playing and Bricolage’. Journal of the American Planning Association 65, no. 1 (31 March 1999): 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369908976031

Joint Publication 5-0 Joint Planning. United States Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2020.

Karlesky, Michael, and Mark Voord. ‘Agile Project Management’, 1 October 2008.

Krogerus, Mikael, and Roman Tschappeler. The Decision Book: Fifty Models for Strategic Thinking. Switzerland: Profile Books, 2011.

Land Warfare Doctrine 5-1-4 Military Appreciation Process. Canberra: Army Knowledge Group, 2015.

Newstrom, John W, and Stephen A. Rubenfeld. ‘The Johari Window: A Reconceptualization’. Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning: Proceedings of the Annual ABSEL Conference 10 (13 March 1983). https://absel-ojs-ttu.tdl.org/absel/article/view/2298

Nipaporn Khamcharoen, Thiyaporn Kantathanawat, and Aukkapong Sukkamart. ‘Developing Student Creative Problem-Solving Skills (CPSS) Using Online Digital Storytelling: A Training Course Development Method’. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning 17, no. 11 (June 2022): 17–34. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v17i11.29931

O’Brien, Michael. ‘Australian Army Tactical and Instructional Pamphlets and Books - A Bibliography’. National Library of Australia, 2002. https://www.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-11/Australian%20Army%20Tactical%20and%20Instructional%20Pamphlets%20and%20Books%20-%20A%20bibliography%282017%29.pdf

Robertson, S. Ian. Types of Thinking. Florence, UK: Taylor & Francis Group, 1999. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/deakin/detail.action?docID=1144439

Skogen, MD, R Ji, A Akimova, U Daewel, C Hansen, SS Hjøllo, SM Van Leeuwen et al. ‘Disclosing the Truth: Are Models Better than Observations?’ Marine Ecology Progress Series 680 (9 December 2021): 7–13. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13574

Storr, Jim. Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century. Hampshire: Howgate Publishing Ltd, 2022.

Strauch, R. ‘Strategic Planning as a Perceptual Process’, 1981. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA136893.

Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. ‘The Black Swan: Why Don’t We Learn That We Don’t Learn?’, nd.

The Art of Reverse Engineering: Open - Dissect - Rebuild. Accessed 9 July 2023. https://eds-s-ebscohost-com.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/ZTAwMHh3d19fODIxNDcwX19BTg2?sid=234d774d-39ac-4497-bcaf-9a75762fd8c9@redis&vid=44&format=EB&rid=7

Williamson, Porter B. General Patton’s Principles for Life and Leadership. 5th ed. Management and Systems Consultants, Inc, 2009.

Zweibelson, Ben. ‘Gravity-Free Decision-Making: Avoiding Clausewitz’s Strategic Pull’, 2015.

———. ‘Linear and Non-Linear Thinking: Beyond Reverse-Engineering’ 16, no. 2 (2016).

1 Australian Defence Force Publication 5.0.1 - Joint Military Appreciation Process, Ed 2 (Canberra: Joint Doctrine Directorate, 2019). P15

2 Michael O’Brien, ‘Australian Army Tactical and Instructional Pamphlets and Books - A Bibliography’ (National Library of Australia, 2002), https://www.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-11/Australian%20Army%20Tactical%20and%20Instructional%20Pamphlets%20and%20Books%20-%20A%20bibliography%282017%29.pdf. P240

3 Allied Joint Publication-5 Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations, Edition A Version 2 (NATO Standards Office (NSO), 2019); Joint Publication 5-0 Joint Planning (United State Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2020).

4 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. P15

5 JP-5 Joint Planning. FigIII-1

6 Allied Joint Publication-5 Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planning of Operations. Chap 4.1

7 Land Warfare Doctrine 5-1-4 Military Appreciation Process (Canberra: Army Knowledge Group, 2015). Chap 1.2

8 Porter B Williamson, General Patton’s Principles for Life and Leadership, 5th ed. (Managment and Systems Consultants, Inc, 2009). P151

9 Michael Karlesky and Mark Voord, ‘Agile Project Management’, 1 October 2008.

10 Ben Zweibelson, ‘Linear and Non-Linear Thinking: Beyond Reverse-Engineering’ 16, no. 2 (2016); Ben Zweibelson, ‘Gravity-Free Decision-Making : Avoiding Clausewitz’s Strategic Pull’, 2015.

11 Kathleen B Hass, ‘The Blending of Traditional and Agile Project Management’, 2007.

12 Anthony Barrett and Daniel S. Weld, ‘Partial-Order Planning: Evaluating Possible Efficiency Gains’, Artificial Intelligence 67, no. 1 (1 May 1994): 71–112,https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-3702(94)90012-4.

13 Barrett and Weld.

14 O’Brien, ‘Australian Army Tactical and Instructional Pamphlets and Books’.

15 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. P1-228

16 LWD 5-1-4 MAP. Chap 9-10

17 Army Leadership Doctrine AC72029 (The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst: Centre for Army Leadership, n.d.).

18 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP.

19 Allied Joint Publication-5 Allied Joint Doctrine for the Planing of Operations. P77

20 ADF Philosophical Doctrine 5 Series Planning, Edition 1st (Canberra: Directorate of Information, Graphics and eResources, 2021). P30

21 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP.

22 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. P23

23 LWD 5-1-4 MAP, P5

24 Army Doctrine Publication 5-0 The Operations Process (Headquarters, Department Of The Army, 2019). Para 2-89

25 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. P77

26 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. P15

27 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. P93

28 ADF Philosophical Doctrine - 3 Series: Campaigns and Operations, Ed 2 AL2 (Canberra: Directorate of Information, Graphics and eResources, 2021). P11

29 ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations. P75-76

30 ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations. P12

31 ADF-P-5 Planning. P43

32 ADF Integrated Doctrine: 0 Series: Command: Headquarters and Staff Functions, Ed 1 (Canberra: Directorate of Information, Graphics and eResources, 2022). P55, P60

33 Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century (Hampshire: Howgate Publishing Ltd, 2022). P127-128

34 Dedre Gentner and Albert L. Stevens, Mental Models (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Taylor & Francis Group, 1983), http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/deakin/detail.action?docID=1596442. P8

35 Md Skogen et al., ‘Disclosing the Truth: Are Models Better than Observations?’, Marine Ecology Progress Series 680 (9 December 2021): 7–13, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13574.

36 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. P13-14

37 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. P25, 70, 92, 186

38 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. P186

39 ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP. P9, 15-17, 22-23, 57-58, 61, 91, 93, 96, 99, 117, 129, 136, 207

40 S. Ian Robertson, Types of Thinking (Florence, UNITED KINGDOM: Taylor & Francis Group, 1999), http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/deakin/detail.action?docID=1144439. P3

41 Hannah Bratterud et al., ‘The Sung Diagram: Revitalizing the Eisenhower Matrix’, in Diagrammatic Representation and Inference, ed. Ahti-Veikko Pietarinen et al., Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020), 498–502, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54249-8_43.

42 Bratterud et al.

43 John W. Newstrom and Stephen A. Rubenfeld, ‘The Johari Window: A Reconceptualization’, Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning: Proceedings of the Annual ABSEL Conference 10 (13 March 1983), https://absel-ojs-ttu.tdl.org/absel/article/view/2298.

44 Mikael Krogerus and Roman Tschappeler, The Decision Book: Fifty Models for Strategic Thinking (Switzerland: Profile Books, 2011). P13

45 R. Strauch, ‘Strategic Planning as a Perceptual Process’, 1981,https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA136893.

46 Newstrom and Rubenfeld, ‘The Johari Window’.

47 David Easley and Jon Kleinberg, ‘The Small-World Phenomenon’, in Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

48 Nassim Nicholas Taleb, ‘The Black Swan: Why Don’t We Learn That We Don’t Learn?’, n.d.

49 Nipaporn Khamcharoen, Thiyaporn Kantathanawat, and Aukkapong Sukkamart, ‘Developing Student Creative Problem-Solving Skills (CPSS) Using Online Digital Storytelling: A Training Course Development Method’, International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning 17, no. 11 (June 2022): 17–34, https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v17i11.29931.

50 Sarah Edwards and Nick Cooper, ‘Mind Mapping as a Teaching Resource’, The Clinical Teacher 7, no. 4 (2010): 236–39, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2010.00395.x.

51 The Art of Reverse Engineering : Open - Dissect - Rebuild, accessed 9 July 2023, https://eds-s-ebscohost-com.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/ZTAwMHh3d19fODIxNDcwX19BTg2?sid=234d774d-39ac-4497-bcaf-9a75762fd8c9@redis&;vid=44&format=EB&rid=7.

52 Judith E. Innes and David E. Booher, ‘Consensus Building as Role Playing and Bricolage’, Journal of the American Planning Association 65, no. 1 (31 March 1999): 9–26,https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369908976031.

53 Emet Gurl, ‘SWOT ANALYSIS: A THEORETICAL REVIEW’, 11 August 2017,http://hdl.handle.net/10673/792.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.