Introduction

The complexity of Australia's geopolitical environment defies traditional linear planning approaches. Historically, military planning approaches were solely grounded in mechanistic, reductionist methods of problem solving.[1] This approach worked effectively for ordered problems in complicated environments; however, contemporary dynamics have changed. The modern complex interactions between national interests, statecraft, and geopolitics means nations may be simultaneously engaged across the spectrum of competition at multiple points.[2] No matter how a nation terms this new paradigm, it is principally concerned with a more dynamic operating environment, seeing both traditional and non-traditional actors employing state-equivalent instruments of power with novel, adaptive and surprising efficiencies.[3] Operation Desert Storm—seen as either the last industrial war or the first informational war—represented the apparent evolution of operational complexity driven by computing and technological advances.[4] This shift demonstrated the changing character of war and conflict caused by unprecedented speed, lethality, manoeuvre, and precision.[5]

There are no universal approaches to addressing the growing complexity of the operational environment. In the absence of any commonly accepted military planning process, various international methodological and technological approaches have emerged to enable commanders and planners to address military problems.[6] The Australian Defence Force (ADF) currently addresses planning philosophically through Australian Defence Doctrine Publications (ADDP) and procedurally via Australian Defence Force Procedures (ADFP).[7] The core of this planning architecture that guides both campaign and operational planning is the ADFP 5.0.1—Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP).[8] The ADFP 5.0.1—JMAP is derived from a traditional linear process that is applied in a lockstep manner with allowances for repeating, reordering or omitting steps.[9] With its origin in traditional military thinking, the JMAP has sporadically integrated elements of planning and problem solving drawn from military design to account for its deficiencies derivative from the increasing complexities of the contemporary operational environments.[10] Accordingly, this paper analyses the JMAP through the lens of two core concepts shaping both traditional military planning and military design—complexity theory and systems thinking. Through this approach, an evaluation of the JMAP’s effectiveness will be possible.

This essay argues that JMAP's cursory integration of design thinking undermines the application of complexity theory and systems thinking, thereby weakening modern planning outcomes. Section One commences this argument by examining traditional military thinking and its growing dependencies on military design—a standalone, comparative planning process essential for problems in complex systems. Subsequently, Section Two analyses the JMAP’s current application of complexity theory and how this reflects the JMAP’s superficial integration of traditional planning and military design principles. The final section identifies the inadequacies of the ADF’s application of systems thinking and how this affects the integration of traditional planning and military design. Having scrutinised the intersections of these processes and their integration into the JMAP, this paper proposes that the JMAP needs an improved planning approach driven by a more sophisticated application of planning philosophies.

Section One – Traditional military planning and its growing relationship with design

Contemporary military planning struggles to meet the challenges of 21st-century warfare. The origins of what could be recognised as modern military planning appeared in the 1920s with the development of the concept of operational art in response to the changing strategy, nature of operations, and military structures.[11] The characteristic of this process was, and still is, defined and influenced by its inherent linear nature, scientific and mechanical heritage, reliance on convergent (critical) thinking, and pursuit of a terminal end state grounded in industrial age warfare.[12] Traditional military planning attempts to partition the component elements of systems and independently dissect them to determine their finite structure and dependencies.[13] While such reductionism is effective in complicated operations, this traditional military approach falls short of the complex systems of 21st-century operational environments, where adversaries defy established norms and the traditional military advantages of great powers have been significantly diminished.[14]

Military practitioners have increasingly adopted military design to address the inherent limitations of traditional planning in complex operational environments. This shift towards integration arises from the escalating complexity of modern military operations. [15] However, the endeavour to meld the technical rationalism[16] of traditional planning with reflective constructivist[17] design principles has engendered substantial friction in understanding and implementation over the past three decades.[18] In part, this friction can be attributed to the piecemeal adoption of individual design practices without the incorporation of complementary philosophical components to enable the why and not just the how. A nuanced comprehension of the origins of these processes, coupled with an appreciation for the evolving complexities of the operational landscape, underscores the imperative for this integrative approach.

As the contribution of design methodology in military planning continues to evolve, its significance in navigating complex environments is becoming increasingly evident. While the utility of design is still debated—whether as a rival, complementary, or subset to traditional planning—its application is undeniably expanding to enhance the military's modus operandi in managing complexity.[19] Shaping complex adaptive systems requires a deeper understanding of the constituent elements within the environment.[20] The traditional reflexive action to oversimplify the operational environment must be tempered to foster opportunities to employ genuine divergent (creative) thinking.[21]

Using design's reflective constructivist principles allows for a more comprehensive grasp of the uncertainties and ambiguities inherent in conflict.[22] This approach facilitates a non-linear, improvisational mode of planning, encouraging creative risk-taking and critical reflection, thereby fostering a tailored understanding of the environment. [23] At a minimum, design is a bridge for commanders and military planners to consider significant alternatives in thinking, practice, and ways of organising and influencing systems.[24] To achieve an idealised process, the ADF, along with the United Statesmilitary, the Canadian military, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), have subsumed elements of design philosophy and methodology into joint doctrine’s operational design.[25]

The ADF's current campaign and operational planning doctrine integrates vital elements of traditional and design concepts. While still rationalistic, the doctrine acknowledges operations' inherently non-linear, fluid, ill-defined and complex nature.[26] Further, it acknowledges that solving these problems requires a detailed situational understanding of the system holistically and the shifting interactions of sub-elements.[27] Significantly, ADFP 5.0.1—JMAP has evolved to incorporate scoping and framing, fostering a cognitive approach that ensures holistic system assessment before initiating detailed planning.[28] The doctrine also reinforces that—if required by the circumstances—the process can be applied less rigidly, allowing for steps to be repeated, reordered or omitted where more profound understanding is needed or time-restricted; however, this is rarely seen in practice.[29] While these changes represent the symbiotic amalgamation of both greater creativity and critical thinking, the process is still somewhat convergent and product-driven.[30] As the doctrine continues to evolve towards complexity and systems theory—as the following sections outline—the friction between the two comparative planning processes leads to the misapplication of critical philosophies, inhibiting the desired innovation and creativity design thinking promises.[31]

Section Two – It is not complicated, it is complex

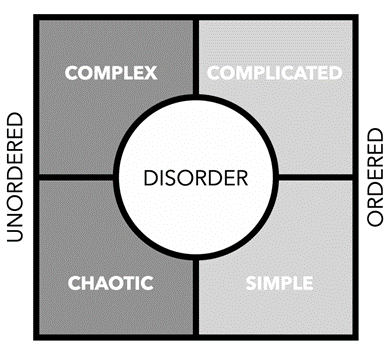

Complexity theory underpins the effectiveness of commanders and practitioners in military planning. Effectively applying this theory will significantly influence operations towards a desired strategic outcome.[32] However, this requires an accurate evaluation and subsequent understanding of the operational environment.[33] While the terms complicated and complex are often used interchangeably in common parlance, they are, in fact, distinct concepts.[34] This may seem trivial to those unfamiliar with complexity theory, but misinterpreting complex systems as merely complicated can profoundly alter both the operational approach and its outcomes.[35] Notably, while higher-level philosophical doctrine distinguishes between complicated and complex systems,[36] the procedural JMAP doctrine identifies systems solely as complex.[37] This discrepancy underscores a fundamental misunderstanding and subsequent misapplication of complexity theory. One model that offers clarity on the nature of systems and is used in both civilian sectors and the ADF's Joint Professional Military Education (JPME) capstone philosophical doctrine is the Cynefin Framework.[38]

The JMAP's narrow focus on complexity undermines the accuracy of operational assessments and the relevance of traditional planning. The JMAP categorises complexity theory into two distinct types: structural and interactive complexity[39]. The doctrine defines structural complexity as ‘existing in a system made up of many parts that operate in a predictable (usually linear) way’.[40] Conversely, interactive complexity is ‘a system that is made up of many parts that interact with each other and with the system itself in many alternating ways, adapting and change over time, often unpredictably.’[41] While these definitions align well with the notion that all modern operations are complex, they fall short in addressing why a primarily linear process designed for complicated environments is still used—or why design elements are incorporated into traditional planning instead of replacing it. This conundrum can be effectively addressed through the application of the Cynefin Framework's interpretation of complexity theory (Figure 1).

Adapted from Snowden and Boone ‘A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making’, 2007

The Cynefin Framework clarifies Australia's military planning by distinguishing the complex from the complicated. While this framework identifies five types of systems—simple, complicated, complex, chaotic, and disorder—only the notions of complicated and complex systems are directly pertinent to Australia's shift towards integrated planning.[42] Grasping these two types of systems, as delineated by the Cynefin Framework, enhances our understanding of complexity theory and underscores the importance of amalgamating design with traditional planning methodologies. Within this framework, complicated systems are ordered problem sets with finite solutions, often able to be linearly deduced to pinpoint the most effective path to the desired outcome.[43] Here, cause-and-effect relationships can also be ascertained through rigorous analysis.[44] In contrast, complex systems within this framework are marked by unpredictability, where the interplay among components is dynamic and confusing.[45] Actions within these systems can trigger unforeseen, cascading effects of varying magnitude and impact.[46] A complex system is inherently holistic; it defies segmentation into independent parts as its unique properties emerge from the interactions among its components.[47] Notably, a unique feature of this framework is that a single system can manifest characteristics of multiple domains simultaneously.[48]

The Cynefin Framework modernises ADF planning, bridging traditional and design methods. Using the framework, modern planners can employ traditional planning methods to address the complicated facets of their problems while also leveraging design to navigate its dynamic, unpredictable, complex elements. If this theoretical framework was integrated into ADFP 5.0.1—JMAP, this epistemological perspective would harmonise the two processes and align with the higher-order ADDP. This would have the effect of clarifying why design methodologies are increasingly essential as operational environments become more complex and why traditional planning is still relevant in the modern era. A nuanced understanding of these distinctions allows each approach to be valued for its unique contributions and perspectives. It underscores that no single methodology is inherently superior; they are merely addressing different requirements.[49] This notion is eloquently captured by retired US Marine Corps General James Mattis, who stated, ‘Design does not replace planning, but planning is incomplete without design’.[50]

Section Three – Unsolved problems in problem solving

The ADF requires a more sophisticated conceptual approach to addressing problems to improve the quality of options available to commanders. Contrary to a prevalent misconception, problems are not objects of direct experience but abstractions of reality.[51] These abstractions are formulated based on desired sociological outcomes driven by a range of motivating factors. Importantly, problems are diachronic in nature, meaning they are perceived through individual lenses, evolve over time, and are influenced by a multitude of variables, thereby requiring a dynamic approach for effective resolution.[52] This diachronic aspect adds another layer of complexity, making it imperative for decision makers to consider both temporal, contextual and sociological factors.

In the realm of planning, specific criteria must be satisfied for a situation to be considered a problem. First, a decision maker or group must have a desired outcome that has a range of possible courses of action (COA) available;[53] next, the choice, when reached, must have a significant impact towards the desired outcomes; lastly, there must be uncertainty inherent in the alternative approaches the decision maker is grappling with.[54] Armed with this nuanced understanding of what constitutes a problem, the task of addressing such issues within the framework of complicated and complex systems remains a formidable challenge, albeit not an unprecedented one.

Ackoff's seminal work provides a nuanced framework for decision-making in complex operational environments. The research of Professor Russell Ackoff, a renowned pioneer in operations research, systems thinking, and management science, tackled the concepts and theories of problems. His work addressing the complexities of today's dynamic corporate environment mirrors those of the military.[55] One of the pivotal contributions of his work is the assertion that planners must first comprehend the nature of the system a problem is situated in to identify the most effective approach for its resolution.[56] Ackoff posits that problems can be categorised based on the type of system they exist within and should be approached in one of three hierarchical manners: they can be resolved, solved, or dissolved.[57]

Without understanding the nuances of resolving, solving, and dissolving, military planners risk suboptimal outcomes in any system. The approaches to problems, as defined by Ackoff, provides the nuances to hone the approaches to decision making. To resolve a problem is to select a Course of Action (COA) that yields an outcome that is good enough to meet the specified intent.[58] This qualitative approach is often applied when addressing problems within complex systems and relies heavily on experience and the extensive use of subjective judgments. It is often applied to challenges that are both ill-defined and time-constrained.[59] On the other hand, solving a problem within complicated systems involves choosing a COA that provides an optimised outcome.[60] This quantitative approach draws extensively on scientific methods, techniques, and tools. It is valued for its comprehensiveness, its ability to generate consensus, and the commitment it engenders to the conclusions reached.[61] However, a notable shortcoming is the tendency to seek an optimal solution for a poorly framed problem rather than a less optimal solution for a completely framed problem.[62] Dissolving a problem entails altering the system where the problem exists, bringing it closer to a desired state where the problem cannot exist or re-emerge.[63] In essence, problem resolution adopts a humanistic, instinctive approach; problem solving employs scientific reasoning and rigour. But only problem dissolution can address contemporary military problems by harmoniously integrating both, treating the humanities and science as complementary facets of the same coin.[64]

The ADF must evolve from mere problem solving to embrace problem dissolution in multifaceted operational systems. Within ADFP 5.0.1—JMAP, the concept of dissolving problems is partially addressed through the integration of design methodologies, such as Scoping and Framing, but falls short in the philosophical articulation of the concept. Problems within complex systems have no immediate means of measuring their effectiveness, have no termination date for their effects, and can only be about better-or-worse outcomes; they are not solvable.[65] Despite this understanding, the term problem appears 88 times in ADFP 5.0.1—JMAP, with solving as the sole prescribed method for addressing them. This narrow focus becomes problematic when one considers that solving is synonymous with traditional planning methods and complicated systems. Conversely, dissolving a problem is inherently tied to an integrated approach that combines design thinking with traditional problem-solving methods.[66] Understanding this dichotomy clarifies the cognitive dissonance commanders and planners may experience when determining the role of design in addressing problems within the current operational paradigm. Ultimately, the ADF must shift from problem solving to problem dissolution to address the increasing complexity of the operational environment. By doing so, the ADF will be able to harmonise the application of the two core concepts of traditional military planning and military design—complexity theory and systems thinking.

Conclusion

This essay has meticulously examined military planning dynamics within the ADF, revealing a vital need for the revision and realignment of the underlying principles that steer the JMAP. The central argument put forth throughout this paper is that the JMAP's superficial integration of traditional planning and design thinking undermines the implementation of complexity theory and systems thinking. The evident conclusion is that the current doctrine falls short of encapsulating the fundamental philosophies essential for the application of design methodologies in complex environments. This inherent deficiency limits the effectiveness of the JMAP in addressing problems across the spectrum of systems.

The complexities and dynamics of contemporary warfare necessitate the development of a forward-thinking doctrine that prioritises complexity theory and problem dissolution. To achieve this imperative transformation, the ADF must commit to a holistic realignment of philosophical understanding to methodological approaches. Integral to this journey of transformation is an unwavering investment in professional military education and a profound appreciation for a diverse array of disciplines. These disciplines encompass sociology, complexity theory, systems thinking, and management theory. Synthesising these multidisciplinary insights will serve as the bedrock upon which the ADF can forge a doctrine responsive to contemporary challenges.

In summary, the ADF's pathway forward lies in the fusion of philosophical understanding and practical methodologies, aligning its planning processes with the complexities of modern warfare. By embracing this paradigm shift, the ADF can navigate the intricate web of challenges that define today's operational environment, ultimately contributing to the preservation of Australian national security and the realisation of strategic objectives in a world marked by perpetual change.

Ackoff, Russell. ‘On the use of models in corporate planning.’ Strategic Management Journal 2, no. 4 (1981). https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2486198.pdf

Ackoff, Russell. ‘OR: after the post-mortem.’ System dynamics review 17, no. 4 (2001). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/sdr.222

Ackoff, Russell. ‘Some unsolved problems in problem solving.’ Journal of the Operational Research Society 13, no. 1 (1962). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1057/jors.1962.1

Ackoff, Russell. ‘The art and science of mess management.’ Interfaces 11, no. 1 (1981). https://www.systemswisdom.com/sites/default/files/Ackoff-1981-Mess-Management_0.pdf

Ackoff, Russell. ‘The Circular Organization: An Update.’ The Academy of Management Executive, no. 1 (1989). https://search.proquest.com/openview/a2954d742e8b9e91e18ced125b40f4cc/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=29357

Ackoff, Russell and Jamshid Gharajedaghi. ‘Reflections on systems and their models.’ Systems Research 13, no. 1 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1735(199603)13:1%3C13::AID-SRES66%3E3.0.CO;2-O

Australian Defence Force. ‘Campaigns and Operations.’ ADF Philosophical Doctrine 3, Series 3 Operations, 3rd ed (2023).

Australian Defence Force. ‘Foundations of Australian Military Doctrine.’ ADF Capstone Doctrine, 4th ed (2021).

Australian Defence Force. ‘Joint Military Appreciation Process.’ Australian Defence Force Procedures, Planning, no. 2 (2019).

Australian Defence Force. ‘Planning.’ ADF Philosophical Doctrine, Series No 5, 1st ed (2021).

Bellas, David. ‘Are linear planning models even more critical as warfare evolves greater complexity?.’ The Forge, War College Papers (2022). https://theforge.defence.gov.au/war-college-papers-2022/are-linear-planning-models-even-more-critical-warfare-evolves-greater-complexity .

Boukhtouta, Abdeslem, Abded Bedrouni, Jean Berger and Adel Guitouni. ‘A survey of military planning systems.’ In The 9th ICCRTS Int, Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium (2004). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228437196_AGuitouni_A_survey_of_military_planning_systems

Boukhtouta, Bedrouni, Berger Bouak, and Andrew Guitouni. ‘A survey of military planning systems.’ In The 9th ICCRTS Int, Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium (2004). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228437196_AGuitouni_A_survey_of_military_planning_systems

Campen, Alan. ‘The First Information War: The Story of Communications, Computers, and Intelligence Systems in the Persian Gulf War.’ Fairfax, VA: Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association (AFCEA), International Press (1992). https://worldcat.org/en/title/1034681741

Checkel, Jeffrey. ‘The constructive turn in international relations theory.’ World politics 50, no. 2 (1998): 324-348. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/wpot50&i=363

Chaliand, Gérard. ‘Guerrilla Strategies: An Historical Anthology from the Long March to Afghanistan.’ Berkeley: University of California Press (1982).

Clark, Andrew. ‘Humility: The Inconspicuous Quality of a Master of War.’ Military Review (2021). https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/JF-21/Clark-Master-of-War-1.pdf

Department of Defence. ‘Joint Professional Military Education (JPME) Continuum.’ Joint Professional Military Education Directorate, Australian Defence College, 2nd Ed (2022).

Dorst, Kees. ‘Design beyond Design.’ She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2019.05.001.

Ehlers, Robert and Patrick Blannin. ‘Integrated Planning and Campaigning for Complex Problems.’ The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters 51, no. 2 (2021). https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3071&context=parameters

Garvey, Bruce. ‘Problem Status.’ In Uncertainty Deconstructed: A Guidebook for Decision Support Practitioners, Cham: Springer International Publishing, (2022). https://books.google.com/books/about/Uncertainty_Deconstructed.html?id=_H-FEAAAQBAJ

Graves, Thomas and Bruce Stanley. ‘Design and Operational Art: A Practical Approach to Teaching the Army Design Methodology.’ Military Review (2013). https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20130831_art011.pdf

Holyoak, Keith. ‘The pragmatics of analogical transfer.’ In Psychology of learning and motivation, Academic Press, vol. 19 (1985); 59-87. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0079742108605241

Jackson, Aaron. ‘The only problem with the operations planning process is that we don’t use it!: Why this argument is invalid.’ Small Wars Journal (2019). https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/only-problem-operations-planning-process-we-dont-use-it-why-argument-invalid

Jackson, Aaron. ‘Thinking in Commerce and War: Contrasting Civilian and Military Innovation Methodologies.’ Air University Press, Lemay Papers, No7 (2020). https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1145583

Jackson, Aaron. ‘Towards a Multi-paradigmatic Methodology for Military Planning: An Initial Toolkit.’ The Archipelago of Design: Researching Reflexive Military Practices (2018). https://aodnetwork.ca/towards-a-multi-paradigmatic-methodology-for-military-planning-an-initial-toolkit/

Kurtz, Chris and David Snowden. ‘The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world.’ IBM Systems Journal, (2003). http://vdc.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Sense-making-in-a-complex-and-complicated-world.pdf

Lindblom, Charles. ‘The Science of Muddling Through.’ Public Administration Review, 19 (1959): 79-88. https://www.jstor.org/stable/973677

Monk, Jeremiah. ‘End state: The fallacy of modern military planning.’ Air War College (2017). https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1042004.pdf

Moss, Tracy. ‘Reframing Integrated Operations as Design Process.’ PhD diss, University of Cincinnati, (2020). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343318855_Reframing_Integrated_Operations_as_Design_Process

Murden, Simon. ‘Purpose in Mission Design: Understanding the Four Kinds of Operational Approach.’ Military Review (2013). https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20130630_art011.pdf

Ryan, Alex. ‘A Personal Reflection on Introducing Design to the US Army.’ The Overlap, (2016). https://medium.com/the-overlap/a-personal-reflection-on-introducing-design-to-the-u-s-army-3f8bd76adcb2.

United States Joint Staff. ‘J-7 Joint and Coalition Warfighting, Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design.’ Version 1.0, USJFCOM Joint Doctrine Division, Suffolk, Virginia (2011). https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pams_hands/opdesign_hbk.pdf

Vasilescu, Cezar. ‘Strategic decision making using sense-making models: The Cynefin framework.’ Defense Resources Management in the 21st Century, no. 6 (2011). http://www.codrm.eu/conferences/2011/13_vasilescu.pdf

Votel, Joseph et al. ‘Unconventional Warfare in the Gray Zone.’ Joint Force Quarterly 80, no. 1 (2016). https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/tr/AD1042004

Zweibelson, Ben. ‘An application of theory: generation military design on the horizon.’ Small Wars Journal 19 (2017). https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/an-application-of-theory-second-generation-military-design-on-the-horizon

Zweibelson, Ben. ‘An application of theory: Second generation military design on the horizon.’ Small Wars Journal 19 (2017). https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/an-application-of-theory-second-generation-military-design-on-the-horizon

Zweibelson, Ben. ‘An awkward tango: Pairing traditional military planning to design and why it currently fails to work.’ Journal of military and strategic studies 16, no. 1 (2015). https://aodnetwork.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Zweibelson_An-Awkward-Tango_2015.pdf

1Cezar Vasilescu, "Strategic decision making using sense-making models: The Cynefin framework," Defense Resources Management in the 21st Century, no. 6 (2011): 68-73; Australian Defence Force. "Foundations of Australian Military Doctrine." ADF Capstone Doctrine, 4th ed (2021): 8; Australian Defence Force, "Campaigns and Operations," ADF Philosophical Doctrine 3, Series 3 Operations, 3rd ed (2023): 19.

2 Australian Defence Force, "Planning," ADF Philosophical Doctrine, No 5, 1st ed (2021): 3; ADF, “Campaigns and Operations,” 66.

3 Ben Zweibelson, "An application of theory: Second generation military design on the horizon," Small Wars Journal 19 (2017).

4 Alan Campen, “The First Information War: The Story of Communications, Computers, and Intelligence Systems in the Persian Gulf War,” Fairfax, VA: Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association (AFCEA), International Press (1992): 1–22; Robert Ehlers and Patrick Blannin, "Integrated Planning and Campaigning for Complex Problems," The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters 51, no. 2 (2021): 10.

5 Campen, “The First Information War,” 1–22.

6 Bedrouni Boukhtouta, Berger Bouak, and Andrew Guitouni, "A survey of military planning systems." In The 9th ICCRTS Int, Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium (2004): 5-7.

7 Australian Defence Force, "Joint Military Appreciation Process," Australian Defence Force Procedures, Planning, no. 2 (2019): 4; Aaron Jackson, “The only problem with the operations planning process is that we don’t use it!: Why this argument is invalid." Small Wars Journal (2019).

8 ADF, “ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP,” 4.

9 ADF, “ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP,” 15.

10 Joseph Votel et al, “Unconventional Warfare in the Gray Zone,” Joint Force Quarterly 80, no. 1 (2016): 102.

11 James, Thomas and Simon Thomas, “Campaign Planning: An Effective Concept for Military Operations Other Than War,” School of Advanced Military Studies, US Army Command and General Staff College, (1997).

12 Jackson, "’The only problem with the operations planning”; Charles Cullen, "From the Kriegsacademie to the Naval War College: The Military Planning Process." Naval War College Review (1970): 6-18; Vasilescu," Strategic decision making”.

13 Aaron Jackson, “Thinking in Commerce and War: Contrasting Civilian and Military Innovation Methodologies,” Air University Press, Lemay Papers, No7 (2020).

14 Jeremiah Monk, “End state: The fallacy of modern military planning. “ Air War College (2017); ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process, 18; Gérard Chaliand, “Guerrilla Strategies: An Historical Anthology from the Long March to Afghanistan,” Berkeley: University of California Press (1982); Robert Ehlers and Patrick Blannin, "Integrated Planning and Campaigning for Complex Problems." The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters 51, no. 2 (2021): 10.

15 Bellas, “Are linear planning models even more critical”; Ben Zweibelson, "An awkward tango: Pairing traditional military planning to design and why it currently fails to work," Journal of military and strategic studies 16, no. 1 (2015); Abdeslem Boukhtouta, Abded Bedrouni, Jean Berger and Adel Guitouni, "A survey of military planning systems," In The 9th ICCRTS Int, Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium (2004): 5-7.

16 Technical rationalism refers to planning processes that are systematic, evidence-based, and objective. Charles Lindblom, "The Science of Muddling Through,” Public Administration Review, 19 (1959): 79-88.

17 Reflective constructivism in military planning acknowledges the influence of non-material factors, such as beliefs, norms, and identity, alongside material factors like military capabilities and geography. Jeffrey Checkel, "The constructive turn in international relations theory," World politics 50, no. 2 (1998): 324-348.

18 Simon Murden, “Purpose in Mission Design: Understanding the Four Kinds of Operational Approach”, Military Review (2013).

19 Thomas Graves and Bruce Stanley, “Design and Operational Art: A Practical Approach to Teaching the Army Design Methodology,” Military Review (2013); Tracy Moss, "Reframing Integrated Operations as Design Process," PhD diss, University of Cincinnati, (2020).

20 Department of Defence, “Joint Professional Military Education (JPME) Continuum,” Joint Professional Military Education Directorate, Australian Defence College, 2nd Ed (2022):45.

21 Department of Defence, “JMPE Continuum,” 45.

22 Zweibelson, "An awkward tango”; Jeremiah, “End state”.

23 Zweibelson, "An awkward tango”; Jeremiah, “End state”.

24 Zweibelson, "An application of theory”.

25 United States Joint Staff, “J-7 Joint and Coalition Warfighting, Planner’s Handbook for Operational Design,” Version 1.0, USJFCOM Joint Doctrine Division, Suffolk, Virginia (2011): 10-11.

26 ADF, “ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP,” 15.

27 ADF, “ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP,” 68.

28 ADF, “ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP,” 4.

29 ADF, “ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP,” 15.

30 Zweibelson, "An application of theory”; Aaron Jackson, “Towards a Multi-paradigmatic Methodology for Military Planning: An Initial Toolkit,” The Archipelago of Design: Researching Reflexive Military Practices (2018).

31 Alex Ryan, “A Personal Reflection on Introducing Design to the U.S. Army,” The Overlap, https://medium.com/the-overlap/a-personal-reflection-on-introducing-design-to-the-u-s-army-3f8bd76adcb2.

32 Monk, “End state”.

33 Bellas, “Are linear planning models even more critical”.

34 Department of Defence, “JMPE Continuum,” 39.

35 ADF, “Planning,” 19.

36 ADF, “Planning,” 19.

37 ADF, “5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process,” 68.

38 Monk, “End state”; Vasilescu, "Strategic decision making using sense-making models,” 68-73; Department of Defence, “JMPE Continuum,” 46.

39 Also defined as a “complex adaptive system” in ADF, “ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP,” 118.

40 ADF, “ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP,” 118.

41 ADF, “ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP,” 118.

42 Zweibelson, "An application of theory”.

43 Monk, “End state”.

44 Monk, “End state”.

45 Monk, “End state”.

46 Department of Defence, “JMPE Continuum,” 39.

47 Russell Ackoff, "OR: after the post mortem," System dynamics review 17, no. 4 (2001): 341-346.

48 Monk, “End state”.

49 Jackson, “Design Thinking in Commerce and War”.

50 ADF, “ADFP 5.0.1 JMAP,” 18.

51 Ackoff, “The Circular Organization,” 11–16.

52 Keith Holyoak, "The pragmatics of analogical transfer," In Psychology of learning and motivation, Academic Press, vol. 19 (1985); 59-87.

53 Bruce Garvey, "Problem Status," In Uncertainty Deconstructed: A Guidebook for Decision Support Practitioners, Cham: Springer International Publishing, (2022): 47-61.

54 Ackoff Russell, "The art and science of mess management," Interfaces 11, no. 1 (1981): 20-26.

55 Russell Ackoff, "On the use of models in corporate planning," Strategic Management Journal 2, no. 4 (1981): 353-359.

56 Russell Ackoff, "Some unsolved problems in problem solving," Journal of the Operational Research Society 13, no. 1 (1962): 1-11.

57 Ackoff, "On the use of models in corporate planning," 353-359.

58 Ackoff, "OR: after the post mortem," 341-346.

59 Ackoff, "The art and science of mess management," 20-26.

60Ackoff, "OR: after the post mortem," 341-346.

61 Russell Ackoff and Jamshid Gharajedaghi, "Reflections on systems and their models," Systems Research 13, no. 1 (1996): 13-23.

62 Ackoff, "On the use of models in corporate planning," 353-359.

63 Ackoff, "The art and science of mess management," 20-26.

64 Ackoff, "OR: after the post mortem," 341-346.

65 Andrew Clark, "Humility, " Military Review (2021); Tracy Moss, "Reframing Integrated Operations as Design Process," PhD diss, University of Cincinnati, (2020); Monk, “End state”.

66 Ackoff, Russell L. "Systems thinking and thinking systems." System Dynamics Review 10, no. 2‐3 (1994): 175-188.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.