Introduction

War requires industry.[2] A war cannot be fought for long with supply chains that crisscross a globalised world.[3] Wars are lost if essential resources, supply chains, manufacturing plants and their corporate headquarters are in foreign lands and hands.[4] [5]

We currently live in a globalised world.[6] A globalised system works best in a peaceful world where cooperation and coexistence reign.[7] As the old wisdom goes, ‘if we trade, everyone benefits and so we won’t need to fight’. The system is based on four pillars: cheap labour, plentiful cheap raw materials, significant means of production and bountiful energy.[8] All four have to coincide to make the system work. Since few nations hold all four, we see the movement of raw materials, labour and energy to the sites where manufacturing plants with economies of scale are located.[9] The main site of global production is China.

Australia finds itself deeply embedded in a globalised system with the design, development and production of key systems and critical components occurring in far-off lands; often in lands home to supposed adversaries, enemies or opponents. Significantly, Australia is a major exporter of minerals[10], energy[11] and primary produce[12] but not of manufactured goods[13]. Our capacity for autarky[14], or self-sufficiency, is significant. With the recent recognition of the ending of the long-held view that a 10-year warning period existed, Australia’s economic system needs adjusted.[15] The adjustments proposed involve ‘onshoring’[16] and in some cases ‘reshoring’[17] industrial capabilities.[18] [19] When war occurs, autarky, land mass, population size and sovereignty reign supreme.[20] [21] To establish new economic and industrial capacity will take some time—it is a marathon, not a sprint.

So, is Australia dreaming about its plan to equip, supply and sustain its forces for a changed or more competitive security environment against the ‘largest entente’[22] the world has ever seen? Can Australia absorb the technology required? Since war means industry, how does Australia’s industry stack up?

This paper will discuss the state of Australia’s industrial readiness to meet the aims of the Defence Strategic Review (DSR)[23], the Trilateral security partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States (AUKUS)[24] and the Defence Industry Development Strategy (DIDS)[25].

To answer the above questions, the scope of this paper will be to review the demand signal and the proposed solution space and then review some key indicators. This paper takes as given Australia’s significant possession of minerals, energy and primary production. To understand our ability to absorb advanced technology and increase manufacturing capacity, it is helpful to understand our current productive state. To do so, we need to examine key indicators such as our manufacturing state, our position on two key technology indexes, our level of national debt, our capacity to provide technically qualified personnel, and the supply of labour. Doing so will give us a reasonable sense of whether we are dreaming or, alternatively, how big the task will be.

What is the demand?

The driver for action is the findings of the DSR[26]. Through the DSR, the Government accepted that neither the Australian Defence Force nor industry was ready for the emerging geo-security and geo-economic epochs.[27] The report states that warning times have evaporated; the armed forces are not fit for purpose[28]; and our adversaries have risen phoenix-like, unexpected and unnoticed.

What is the proposed solution?

Apart from the modernisation of the armed forces to create a viable deterrence, Australia’s economy needs restructuring and accelerated investment in targeted enterprises.[29] [30] Underpinning the military and economic shifts, Australia signed the AUKUS partnership on 15 September 2021.[31] AUKUS is primarily a military technology partnership.[32] AUKUS focuses on Australia acquiring nuclear-powered submarines, trilateral cooperation on advanced cyber mechanisms, artificial intelligence and autonomy, quantum technologies, undersea capabilities, hypersonic and counter-hypersonic, electronic warfare, innovation and information sharing.[33] DIDS followed on 29 February 2024[34] to support industry and supply chain resilience, by funnelling $1 billion over the next four years into long-range fires, theatre logistics, fuel resilience and robotic and autonomous systems enterprises. In addition, broad initiatives focus on innovation, science and technology.[35] The result will be a new ‘sovereign industrial base’, which is ‘strong and resilient’. Surprisingly, ‘[o]nly in limited circumstances is Australian ownership critical to sovereignty’.[36] Sovereignty is generally defined as supreme authority, as well as external autonomy.[37] A key question beyond the scope of this paper is, how much ‘sovereignty’ should Australia have?

Manufacturing in Australia

Manufacturing peaked in Australia in the 1960s at 25% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). Thereafter manufacturing was discouraged, dismantled, or forgotten.[38] The decline of manufacturing is typically explained as due to uncompetitive businesses, high labour costs, the challenges posed by a peripheral location, and the (‘Dutch disease’[39]) effects of Australia’s mining boom.[40] The Government claims Australians are benefiting from global trade that reduces domestic manufacturing.[41] In particular, cheaper imports, providing substantially increased household spending power.[42] The result is higher living standards than otherwise would be the case.[43] Manufacturing as a part of GDP is now approximately 5%.[44] The state of manufacturing has a profound impact on the types of things able to be made, the capacity to train apprentices and the ability to absorb technology. Critically, the depth of manufacturing knowledge, the apprentice-to-master journey, is also missing. Even though blessed with resources that permit autarky, there is no easy way back. [45]

National capabilities index

Australia ranks 27 among 194 states—between Nigeria and Vietnam—on the Composite Index of National Capabilities[46] (CINC). Australia is outranked by regional states such as India at 3, Japan at 4, South Korea at 8, Pakistan at 13, Indonesia at 14, Bangladesh at 23 and Thailand at 25. Studies use the CINC score to compare states, since it focuses on indicators that are salient to an assessment of national power. CINC remains one of the best-known and most accepted methods for measuring national capabilities. JD Singer formulated the CINC in 1963, for the Correlations of War project. The index uses the averages of the percentages of global totals in six categories. The categories represent economic, military and demographic shares of the global totals. As a formula, CINC=(TPR+UPR+ISPR+ECR+MER+MPR)/6.[47] Of the six categories, two—metal[48] production and energy generation—are heavily policy driven. Australia produces little iron, steel, aluminium or critically, industrial energy to feed national capability, due in part to the decision to export the bulk of our iron ore, coal and gas in support of globalisation.[49]

Industrial Complexity index

Australia ranks 91/133 in the Harvard Index of Economic Complexity[50] (HIEC) and sits between Kenya and Namibia in the bottom third of states. In addition, Australia is the lowest ranked OECD country, despite its high level of wealth. Economic complexity includes productive knowledge, production capability and the sophistication and diversity of commonly exported goods, compared to other exporting countries. The value of the economic index is in its ability to predict future growth. Countries that have diversified their production into more complex sectors, like Vietnam and China, are those that will lead growth in the coming decades.[51] A Harvard report states that, ‘Australia has not yet started the traditional process of structural transformation. A key source of economic growth, this process reallocates economic activity from low to high productivity sectors. It broadly moves activities out of agriculture into textiles, followed by electronics and/or machinery manufacturing.’[52] Raising the nation’s manufacturing capacity requires long-term policy direction and co-investment from the government and private sources. However, no information is available to indicate the time, effort and money required to shift Australia’s position to a ‘point of sufficient autarky’ that can meet the needs of the DSR.

National debt

The 2021-22 federal Budget projected that the Australian government’s gross debt would increase to $1 199 billion (around 50% of GDP) by 30 June 2025.[53] Net debt peaks at $981 billion or 40.9% of GDP in 2024–25; then falls to 37% of GDP at 30 June 2032.[54] GDP figures need to be interrogated (which is beyond the scope of this study) since they include financial transactions as well as physical productive elements. To make war, the physical trumps the virtual. To support the DSR, Australian debt is likely to increase to fund industrial expansion. ‘Expansion, either by investment or subsidy, will by necessity go to foreign owned organisation, increasing the debt, as no Australian company has the capability to act as ‘prime vendor’. The trend seems to follow the Americans and head to 130% debt to GDP or Japan’s 264%. A rate very different from Russia’s 17% or China’s 77%. Historically, debt-to-GDP ratios above 77% hinder economic growth and (in some cases) place a country at risk of defaulting, which wrecks its economy[55] and financial markets.[56] [57] Higher debt-to-GDP ratios have been used by some countries in the belief that inflation will eat down the debt faster than interest is incurred, and should that fail they always have the option of increasing taxes to cover the debt.

Science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM) qualifications

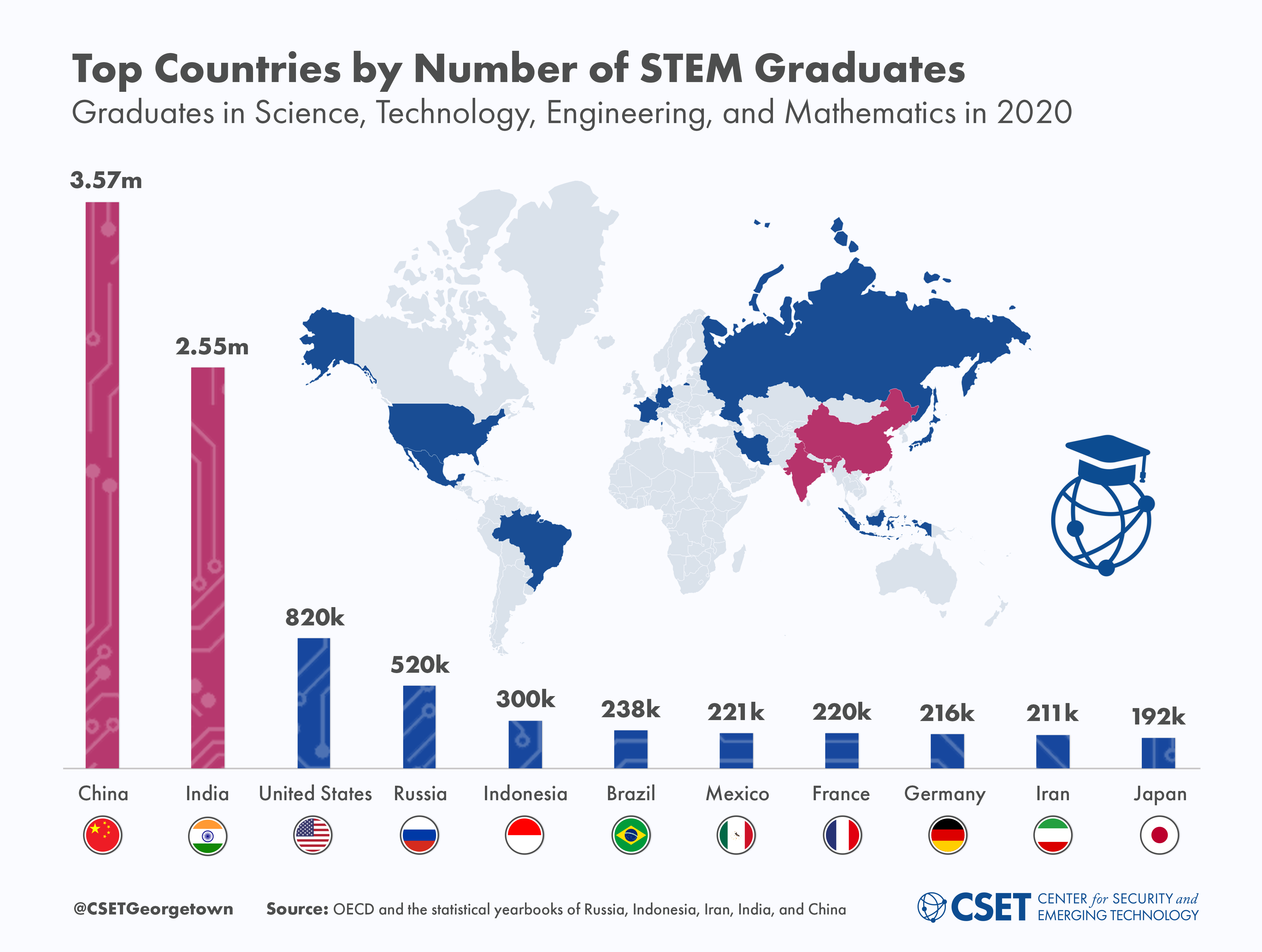

Throughout the 20th century, the United States and Europe—particularly Russia, Germany, Britain, and France were the global centres of scientific and technological education. In the last few decades, China, India, South Korea, and Japan have rapidly expanded their STEM programs and today produce significant numbers of STEM graduates.[58] The global spread of STEM graduates for 2020 is below and Australia is not in the top 10.

In Australia, 442,000 people are studying in a STEM field.[59] [60] [61] The split between Australian and foreign students is difficult to isolate. Of those, 11% study engineering and related technologies (20% of overall male students and 3% of female students).[62] A further 297,000 people aged 15-74 are apprentices or trainees.[63] Only 8.5 per cent of graduates in Australia graduate with an engineering qualification—the sixth lowest proportion among OECD countries.[64] The 70% increase in engineers from 2015–21 was from foreign-born engineers. Demand for engineering skills outpaced supply despite an increase in qualified engineers from 2016–21.[65] The demand increased three times faster than the general workforce.[66] The numbers are insufficient to meet the current, let alone expanded, need.[67] The numbers in comparison to the rest of the world (in the chart above) are also telling.

Unemployment rate

Australia’s population has hit 27 million.[68] Australia's seasonally adjusted unemployment rate in February 2024 was 3.7%. The rate is less than the market forecasts of 4.0%, with a participation rate of 66.7% and under-employment of 6.6%.[69] [70] The unemployment rate from 1991 to 2024 has declined from 9.6% to 3.7%. In essence, there is little spare capacity to create new or expanded industries. The solution is to import workers through a large increase in immigration.[71] [72]. Migration increased Australia’s population by 659 800 in the year to September 2023—roughly 2000 a day.[73] To keep the unemployment rate steady and to cope with the migration rate, Australia needs around 35 000 new jobs per month. Australia is already suffering a housing crisis, so the first jobs will need to be in the construction of over 60,000 dwellings before that labour force can be shifted to strategically more important areas, including support for the DSR.[74]

Conclusion

Australia has identified that its geo-strategic and geo-economic situation has changed. The most significant element of change has been the evaporation of the 10-year warning period that underpinned previous national strategies. To meet the needs of the new situation, Australia plans to modernise its armed forces and restructure, expand and prioritise parts of its industrial capabilities.

Since war means industry, how Australia’s industry stacks up provides the basis for meeting national objectives. While blessed with immense natural resources, Australia faces significant obstacles absorbing advanced technology and converting that technology into effective, efficient and economic industries which can support the DSR, AUKUS or DIDS. Critically, due to Australia’s previous embrace of globalism, significant effort, resources and time will be needed to shift priorities to absorb the advanced technology such as: nuclear-powered submarines, advanced cyber mechanisms, artificial intelligence and autonomy, quantum technologies, undersea capabilities, hypersonic and counter-hypersonic, electronic warfare, innovation and information sharing systems.

A quick look at Australia’s manufacturing state, two internationally recognised technology indices, the level of national debt, the numbers of STEM graduates and the unemployment rate. indicates that the DSR, AUKUS and DIDS strategists might be ‘dreaming’ or may have underestimated the size of the task. With enough time, most things are possible and it may be possible to meet the identified objectives. However, the loss of ‘warning time’ is deeply harmful. The low industrial complexity scores place the technological parts of the AUKUS pillars at risk and probably mean that the local manufacture of nuclear-powered submarines is also at risk.

The bleak picture painted by the assessment highlights the negative consequences of the long-term and deliberate effort at de-industrialisation of both our military and civilian industrial complexes. The shift has seen the gradual disappearance of expertise, technical skills and, critically, machine tools.[75] The result of de-industrialisation restricts the ability to transition innovation from academia to the market and onto the military. The result is we currently import the technology, systems and complexes needed as finished products from international primes[76]. Recognition of our lack of significant sovereign commercial entities leads to the DIDS stating that ‘[o]nly in limited circumstances is Australian ownership critical to sovereignty’.

To rectify the poor start state we find ourselves in requires urgent efforts to rebuild Australian capabilities. All Australians, whether political leaders or captains of industry, academics or financiers, even students, all need to work together for the long haul.

The Castle (1997 Australian film) - Wikipedia Accessed 28/03/24

https://www.tftc.io/content/files/2022/08/Zoltan-Pozsar---War-and-Industrial-Policy.pdf Accessed 24/04/24

A return to old-school mercantilism? | Lowy Institute Accessed 24/04/24

Economy of Nazi Germany - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

Globalization - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

Subsidies Under the Future Made in Australia Act Could Continue Forever: Productivity Commission | The Epoch Times Accessed 28/03/24

https://www.tftc.io/content/files/2022/08/Zoltan-Pozsar---War-and-Industrial-Policy.pdf Accessed 24/04/24

Commodity Summaries | Australia's Identified Mineral Resources 2021 (ga.gov.au) Accessed 26/04/24

Agricultural trade | Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (dfat.gov.au) Accessed 26/04/24

Australia's manufactures exports | Treasury.gov.au Accessed 26/04/24

Autarky - Wikipedia Accessed 28/03/24

National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 | About | Defence Accessed 24/04/24

Offshoring - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

Defence Industry Development Strategy | About | Defence Accessed 24/04/24

Do we want Australia's economy to become more self-sufficient? - ABC News Accessed 24/04/24

Putin's Thesis (Raw Text) - The Atlantic Accessed 24/04/24

Economy of Nazi Germany - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

How will a new security and economic epoch affect Australia | Future Forge (defence.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24.

National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 | About | Defence Accessed 28/03/24

Public version - Release of the inaugural National Defence Strategy Accessed 26/04/24 (publicly available version)

Defence Industry Development Strategy | About | Defence Accessed 26/04/24

The Defence Strategic Review has triggered one of the greatest shifts in Australia's military since WWII. Here's what will change - ABC News Accessed 28/03/24

Public version - Release of the inaugural National Defence Strategy Accessed 26/04/24 (publicly available version)

AUKUS - Wikipedia Accessed 26/04/24

Defence Industry Development Strategy | About | Defence Accessed 26/04/24 (factsheet)

Sovereignty - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

Sally Weller, Phillip O’Neill, De-industrialisation, financialisation and Australia’s macro-economic trap, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, Volume 7, Issue 3, November 2014, Pages 509–526, https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu020 Accessed 26/04/24

Dutch disease - Wikipedia Accessed 26/04/24

Australia's manufactures exports | Treasury.gov.au Accessed 28/03/24

Manufacturing in Australia - Wikipedia Accessed 28/03/24

Manufacturing is the answer to improving Australia’s falling complexity ranking - ADVANCED MANUFACTURING GROWTH CENTRE (amgc.org.au) Accessed 28/03/24

Composite Index of National Capability - Wikipedia Accessed 28/03/24

Defending and supporting an open global economy | Foreign Policy White Paper (dfat.gov.au) Accessed 24/04/24

The Atlas of Economic Complexity (harvard.edu) Accessed 28/03/24

Budget 2021 - 2022: Budget Strategy and Outlook Accessed 28/03/24

Debt to GDP Ratio by Country 2024 (worldpopulationreview.com) Accessed 28/03/24

30 Countries with Highest Debt-to-GDP: 2024 Rankings (yahoo.com) Accessed 26/04/24

The Global Distribution of STEM Graduates: Which Countries Lead the Way? | Center for Security and Emerging Technology (georgetown.edu) Accessed 28/03/24

Education and Work, Australia, May 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24

2020 Australia's STEM Workforce Report | Chief Scientist Accessed 24/04/24

University enrolment and completion in STEM and other fields | STEM Equity Monitor | Department of Industry Science and Resources Accessed 26/04/24

Education and Work, Australia, May 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24

Statistics | Engineers Australia Accessed 26/04/24

Education and Work, Australia, May 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24

Population clock and pyramid | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24

Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24

Australia Unemployment Rate (tradingeconomics.com) Accessed 28/03/24

Migration rose by one-third last year to lift Australia’s population by a record 659,000 | Australian immigration and asylum | The Guardian Accessed 28/03/24

What’s behind the recent surge in Australia’s net migration – and will it last? (theconversation.com) Accessed 28/03/24

Migration rose by one-third last year to lift Australia’s population by a record 659,000 | Australian immigration and asylum | The Guardian Accessed 28/03/24

How tens of thousands of 'missing' homes could push Australia's property prices even higher - ABC News Accessed 28/03/24

Corporate Grime - with the Prof and the Hack (podcast) - Andrew Schmulow and Anthony Klan | Listen Notes Accessed 26/04/24

1 The Castle (1997 Australian film) - Wikipedia Accessed 28/03/24. The quote is ‘Tell him he’s dreaming.’

2 https://www.tftc.io/content/files/2022/08/Zoltan-Pozsar---War-and-Industrial-Policy.pdf Accessed 24/04/24

3 A return to old-school mercantilism? | Lowy Institute Accessed 24/04/24

4 A return to old-school mercantilism? | Lowy Institute Accessed 24/04/24

5 Economy of Nazi Germany - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

6 Globalization - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

7 Subsidies Under the Future Made in Australia Act Could Continue Forever: Productivity Commission | The Epoch Times Accessed 28/03/24

8 https://www.tftc.io/content/files/2022/08/Zoltan-Pozsar---War-and-Industrial-Policy.pdf Accessed 24/04/24

9 https://www.tftc.io/content/files/2022/08/Zoltan-Pozsar---War-and-Industrial-Policy.pdf Accessed 24/04/24

10 Commodity Summaries | Australia's Identified Mineral Resources 2021 (ga.gov.au) Accessed 26/04/24

11 Commodity Summaries | Australia's Identified Mineral Resources 2021 (ga.gov.au) Accessed 26/04/24

12 Agricultural trade | Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (dfat.gov.au) Accessed 26/04/24

13 Australia's manufactures exports | Treasury.gov.au Accessed 26/04/24

14 Autarky - Wikipedia Accessed 28/03/24

15 National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 | About | Defence Accessed 24/04/24

16 Offshoring - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

17 Offshoring - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

18 Defence Industry Development Strategy | About | Defence Accessed 24/04/24

19 Do we want Australia's economy to become more self-sufficient? - ABC News Accessed 24/04/24

20 Putin's Thesis (Raw Text) - The Atlantic Accessed 24/04/24

21 Economy of Nazi Germany - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

22 How will a new security and economic epoch affect Australia | Future Forge (defence.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24. Russia, Iran and China are openly considered the new ‘axis of evil’ (actually a triangle) threatening the ‘rules-based order’ to ‘global security’.

23 National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 | About | Defence Accessed 28/03/24

24 Public version - Release of the inaugural National Defence Strategy Accessed 26/04/24 (publicly available version)

25 Defence Industry Development Strategy | About | Defence Accessed 26/04/24

26 National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 | About | Defence Accessed 28/03/24

27 The Defence Strategic Review has triggered one of the greatest shifts in Australia's military since WWII. Here's what will change - ABC News Accessed 28/03/24

28 The Australian Defence Forces are poorly configured, postured and positioned

29 Public version - Release of the inaugural National Defence Strategy Accessed 26/04/24 (publicly available version)

30 Public version - Release of the inaugural National Defence Strategy Accessed 26/04/24 (publicly available version)

31 AUKUS - Wikipedia Accessed 26/04/24

32 AUKUS - Wikipedia Accessed 26/04/24

33 AUKUS - Wikipedia Accessed 26/04/24

34 Defence Industry Development Strategy | About | Defence Accessed 26/04/24

35 Defence Industry Development Strategy | About | Defence Accessed 26/04/24

36 Defence Industry Development Strategy | About | Defence Accessed 26/04/24 (factsheet)

37 Sovereignty - Wikipedia Accessed 24/04/24

38 Sally Weller, Phillip O’Neill, De-industrialisation, financialisation and Australia’s macro-economic trap, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, Volume 7, Issue 3, November 2014, Pages 509–526, https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu020 Accessed 26/04/24

39 Dutch disease - Wikipedia Accessed 26/04/24

40 Sally Weller, Phillip O’Neill, De-industrialisation, financialisation and Australia’s macro-economic trap, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, Volume 7, Issue 3, November 2014, Pages 509–526, https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu020 Accessed 26/04/24

41 Australia's manufactures exports | Treasury.gov.au Accessed 28/03/24

42 Australia's manufactures exports | Treasury.gov.au Accessed 28/03/24

43 Australia's manufactures exports | Treasury.gov.au Accessed 28/03/24

44 Manufacturing in Australia - Wikipedia Accessed 28/03/24

45 Manufacturing is the answer to improving Australia’s falling complexity ranking - ADVANCED MANUFACTURING GROWTH CENTRE (amgc.org.au) Accessed 28/03/24

46 Composite Index of National Capability - Wikipedia Accessed 28/03/24

47 The variables are: TPR=total population of a country ratio, UPR=urban population of a country ratio, ISPR=iron and steel production of a country ratio, ECR=primary energy consumption ratio, MER=military expenditure ratio, MPR=military personnel ratio.

48 Especially, iron and steel.

49 Defending and supporting an open global economy | Foreign Policy White Paper (dfat.gov.au) Accessed 24/04/24

50 The Atlas of Economic Complexity (harvard.edu) Accessed 28/03/24

51 The Atlas of Economic Complexity (harvard.edu) Accessed 28/03/24

52 Manufacturing is the answer to improving Australia’s falling complexity ranking - ADVANCED MANUFACTURING GROWTH CENTRE (amgc.org.au) Accessed 28/03/24

53 Budget 2021 - 2022: Budget Strategy and Outlook Accessed 28/03/24

54 Budget 2021 - 2022: Budget Strategy and Outlook Accessed 28/03/24

55 Philip II of Spain defaulted on debt four times – in 1557, 1560, 1575 and 1596. These defaults threw the German banking houses into chaos and ended the reign of the Fuggers as Spanish financiers. Greece became the first developed country to default to the International Monetary Fund. In June 2015, Greece defaulted on a $1.7 billion payment to the IMF. Argentina defaulted in May 2020, when the government failed to pay $500m to creditors– at the time, its ninth default.

56 Debt to GDP Ratio by Country 2024 (worldpopulationreview.com) Accessed 28/03/24

57 30 Countries with Highest Debt-to-GDP: 2024 Rankings (yahoo.com) Accessed 26/04/24

58 The Global Distribution of STEM Graduates: Which Countries Lead the Way? | Center for Security and Emerging Technology (georgetown.edu) Accessed 28/03/24

59 Education and Work, Australia, May 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24

60 2020 Australia's STEM Workforce Report | Chief Scientist Accessed 24/04/24

61 University enrolment and completion in STEM and other fields | STEM Equity Monitor | Department of Industry Science and Resources Accessed 26/04/24

62 Education and Work, Australia, May 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24

63 Education and Work, Australia, May 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24

64 Statistics | Engineers Australia Accessed 26/04/24

65 Statistics | Engineers Australia Accessed 26/04/24

66 Statistics | Engineers Australia Accessed 26/04/24

67 Education and Work, Australia, May 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24

69 Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) Accessed 28/03/24

70 Australia Unemployment Rate (tradingeconomics.com) Accessed 28/03/24

71 Migration rose by one-third last year to lift Australia’s population by a record 659,000 | Australian immigration and asylum | The Guardian Accessed 28/03/24

72 What’s behind the recent surge in Australia’s net migration – and will it last? (theconversation.com) Accessed 28/03/24

73 Migration rose by one-third last year to lift Australia’s population by a record 659,000 | Australian immigration and asylum | The Guardian Accessed 28/03/24

74 How tens of thousands of 'missing' homes could push Australia's property prices even higher - ABC News Accessed 28/03/24

Defence Mastery

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.