Contested Access and Manoeuvre in Context

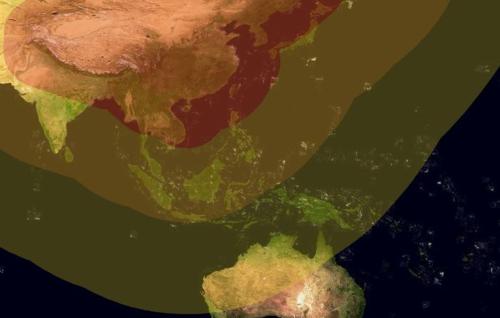

Contested Access and Manoeuvre (CAM) concepts must be applied to the Australian context in order to benefit Australia. Firstly, the threat from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) contesting access and manoeuvre in the region should be considered. Figure 1 shows a sample of People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force missile threats, produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies in 2021.[1] At first glance, the PRC has significant long-range weapons capable of reaching the Australian mainland. Figure 1 shows that the number of missiles capable of reaching 3000 kilometres is approximately 25% of the number reaching less than 1000 kilometres. However, because of the increased area at longer ranges, the weapons per unit of area is approximately 6% of that inside 1000 kilometres.[2] For missiles capable of going further than 3000 kilometres, the numbers become 10%, reducing to 2% coverage due to area.[3] This illustrates that the area within 1000 kilometres is highly contested, but the intensity drops markedly outside this range. The vulnerability of long-range kill chains to disruption further exacerbates this effect. This highlights the weakening effects of counter-access and counter-manoeuvre activities at extended projection ranges.[4]

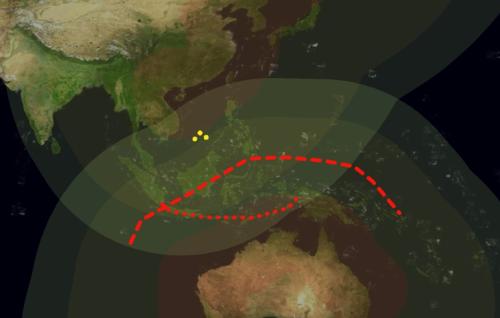

Defending forces can capitalise on the reduced intensity of threat counter-access and counter-manoeuvre activities at long range. Figure 2 shows the reducing intensity of China’s CAM areas overlaid with the increasing intensity of Australia’s. This illustrates Clausewitz’s concept of defence as the stronger form of war.[6] Adversary forces projecting towards Australia must progressively move away from the areas where their CAM capabilities protect them. Simultaneously, they move closer to the areas where Australia’s counter-access and counter-manoeuvre effects intensify. This provides Australia with an asymmetric advantage and supports the strategy of denial. The denial effect may be strengthened by conducting long-range effects that reduce the manoeuvre potential of the enemy at the early stages of an attack. Long-range effects require investment in the targeting enterprise and sensor networks to overcome the weaknesses identified earlier. Layering interdependent counter-manoeuvre and counter-access effects with increasing intensity as the threat increases offers Australia the ability to defend against and defeat acts of aggression.

Conclusion

When Australia adopted a strategy of denial in the 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS), it implicitly signalled a need to adopt A2/AD concepts. However, the lack of clear definition surrounding A2/AD terminology and historical biases in describing threat activities hindered its incorporation into the strategy. ‘Contested Access and Manoeuvre’ is a concept that better meets the needs of Australia’s strategy of denial. ‘Contested’ implies the need to conduct counter-access and counter-manoeuvre activities as well as to operate inside environments subjected to the same activities by an adversary. Counter-access and counter-manoeuvre are layered, interdependent activities that support each other across the levels of war. Counter-access is a specifically targeted activity that aims to prevent access to an area. Counter-manoeuvre seeks to limit an enemy’s freedom of manoeuvre. The intensity of counter-access and counter-manoeuvre activities increases commensurately with threat levels. As adversaries operate further from the protection of their capabilities and closer to the strengths of Australia’s systems, it confers an asymmetric advantage to Australia. This allows Australia to capitalise on the strengths of the defence. However, Australia must be willing to project forward to generate layered effects to maximise contested access and manoeuvre benefits. Long-range effects require investment in the targeting enterprise and long-range sensor networks, as well as the sustainment to support it. ‘Contested Access and Manoeuvre’ addresses language and historical barriers to including A2/AD concepts in a strategy of denial.

Adopting ‘Contested Access and Manoeuvre’ will facilitate clearer discussions and debate around the applicable concepts. It provides a conceptual basis for incorporating and apportioning the required capabilities into the strategy of denial. Further analysis of the concept may reveal critical terrain areas to support denial. These may then be matched with appropriate capabilities or investments. The conceptual thought facilitates creative thinking about how varying effects may be delivered to achieve an asymmetric advantage. Layering effects with increasing intensity provides focus to force design activities for apportioning investment, which will lead to more efficient Defence spending. The concept is broad enough in definition to be adaptable to other circumstances or domains.

The concept of ‘Contested Access and Manoeuvre’ in this paper focussed primarily on the physical aspects of the air-sea gap to Australia’s north. It details how distance may be utilised to facilitate Australia’s strategy of denial. However, the concepts discussed are broad and may be adapted to specific circumstances. Such adaptations may include contested access and manoeuvre entirely confined to cyberspace or focussed on the information environment. These particular adaptations may then be incorporated into the overall concept. ‘Contested Access and Manoeuvre’ improves the language and concepts introduced with A2/AD. It allows more meaningful debate around the concepts and inclusion into a strategy of denial. To deliver against the NDS and achieve a strategy of denial, Australia should consider adopting ‘Contested Access and Manoeuvre’ into the ADF Concept Framework.

Air and Space Power Centre. ADF-I-3 ADF Air Power. 1st ed. Doctrine Directorate, 2023.

Australian Government. Integrated Investment Program. Department of Defence, 2024.

———. National Defence Strategy. Department of Defence, 2024.

Badowski, Russell S. “Airpower Projection in the Antiaccess/Area-Denial Environment: Dispersed Operations and Base Defense.” Defending Air Bases in an Age of Insurgency. Air University Press, 2019.https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep19551.15.

Barrie, Douglas. “Anti-Access/Area Denial: Bursting the ‘No-Go’ Bubble?” IISS, March 29, 2019.https://www.iiss.org/en/online-analysis/military-balance/2019/04/anti-access-area-denial-russia-and-crimea/.

Beagle, Lt. Gen. Milford, Brig. Gen. Jason C. Slider, and Lt. Col. Matthew R. Arrol. “The Graveyard of Command Posts: What Chornobaivka Should Teach Us about Command and Control in Large-Scale Combat Operations.” Military Review, June 2023, 10–24.

Blizzard, Timothy J. “The PLA, A2/AD and the ADF: Lessons for Future Maritime Strategy.” Security Challenges 12, no. 3 (2016): 61–82.

Centre for Defence Leadership and Ethics. ADF-P-0 Command. 1st ed. Doctrine Directorate, 2024.

Clausewitz, Carl von. On War. Edited by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. First paperback printing. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Davis, Malcolm. “An Anti-Access/Area-Denial Capability for Australia?” The Strategist, November 25, 2019.https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/an-anti-access-area-denial-capability-for-australia/.

———. “Forward Defence in Depth for Australia.” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2019.https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep23031.

———. “National Defence Strategy: Impactful Projection Constrained.” The Strategist, April 24, 2024.https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/defence-strategic-review-impactful-projection-constrained/.

———. “The ADF Needs to See at Long Range to Strike at Long Range.” The Strategist, January 24, 2023.https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/the-adf-needs-to-see-at-long-range-to-strike-at-long-range/.

Department of Defence. The Defence of Australia 1987. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1987.

Doctrine Directorate. ADF-C-0 Australian Military Power. 2nd ed. Doctrine Directorate, 2024.

———. ADF-I-3 Targeting. 1st ed. Doctrine Directorate, 2023.

———. ADF-P-3 Campaigns and Operations. 3rd ed. Doctrine Directorate, 2023.

Dougherty, Chris. “Moving Beyond A2/AD,” December 3, 2020.https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/moving-beyond-a2-ad.

Edwards, Colby B. “Enabling a Three-Dimensional Integrated Defense.” Defending Air Bases in an Age of Insurgency. Air University Press, 2019.https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep19551.13.

Fuquea, David C. “Advantage Japan: The Imperial Japanese Navy’s Superior High Seas Refueling Capability.” Journal of Military History 84, no. 1 (January 1, 2020): 213–35.

Hellyer, Marcus, and Andrew Nicholls. “‘Impactful Projection’: Long-Range Strike Options for Australia,” December 12, 2022.http://www.aspi.org.au/report/impactful-projection-long-range-strike-options-for-australia.

Hooft, Paul van, Nora Nijboer, and Tim Sweijs. “Raising the Costs of Access : Active Denial Strategies by Small and Middle Powers against Revisionist Aggression.” Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, January 1, 2021.

Houston, Angus, and Stephen Smith. National Defence: Defence Strategic Review: 2023. Canberra: Department of Defence, 2023.

Joint Chiefs of Staff. Joint Publication 3-0 Joint Operations Change 1. United States Department of Defense, 2018.

Joint Doctrine Centre. ADDP 3.22 Force Protection. 1st ed. Operations Series. Defence Publishing Services, 2015.

Joint Warfare Development Branch. ASPIRE, Australian Defence Force Theatre Concept. 2nd ed. Joint Concepts, 2023.

Karako, Tom, and Masao Dahlgren. “Complex Air Defense: Countering the Hypersonic Missile Threat.” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2022.https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep39470.

Kearn, David W. “Air-Sea Battle and China’s Anti-Access and Area Denial Challenge.” Orbis 58, no. 1 (December 2014): 132–46.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2013.11.006.

Keir, Air Commodore Richard. “The Rise of China and the US Response: Time for Australia to Think about Anti-Access and Area-Denial Warfare.” Indo-Pacific Strategic Papers, May 2016.

Marinus. “Marine Corps Maneuver Warfare - The Historical Context.” Marine Corps Gazette, The Maneuverist Papers, September 2020.https://www.mca-marines.org/wp-content/uploads/Marine-Corps-Maneuver-Warfare-1.pdf.

———. “On Defeat Mechanisms - Maneuverist Paper No. 10.” Marine Corps Gazette, The Maneuverist Papers, July 2021.https://www.mca-marines.org/wp-content/uploads/On-Defeat-Mechanisms.pdf.

Miller, Stephen W. “BREAKING A2D2 WITH LONG RANGE FIRES: Enhancing the Delivery of Long Range Precision Fires (LRPF) Is Being Driven Largely as a Potential Response to the Increasing Presence of A2/AD (Anti-Access Area Denial) Defences on the Battlefield.” Armada International, no. 1 (February 1, 2021): 34–38.

———. “MULTI-LAYERED SHIELD: Anti-Access Area Denial (A2AD) Has Taken on Significant Importance as Military Minds Reset to Peer-to-Peer Conflict from Two Decades of Asymmetric Warfare.” Armada International, no. 5 (October 1, 2019): 28–31.

Missile Defense Project. “Missiles of China.” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 12, 2021.https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/china/.

Noorman, Randy. “The Return of the Tactical Crisis.” Modern War Institute, March 27, 2024.https://mwi.westpoint.edu/the-return-of-the-tactical-crisis/.

“ODIN - OE Data Integration Network.” Accessed September 11, 2024.https://odin.tradoc.army.mil/WEG/.

Pezzullo, Michael. “The Long Arc of Australian Defence Strategy.” The Strategist, May 10, 2024.https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/the-long-arc-of-australian-defence-strategy/.

Richardson, John. “Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson: Deconstructing A2AD.” Text. The National Interest. The Center for the National Interest, October 3, 2016.https://nationalinterest.org/feature/chief-naval-operations-adm-john-richardson-deconstructing-17918.

Russell, Alison Lawlor. “Strategic Anti-Access/Area Denial in Cyberspace.” In 2015 7th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Architectures in Cyberspace, 153–68. Tallinn, Estonia: IEEE, 2015.https://doi.org/10.1109/CYCON.2015.7158475.

Schmidt, Todd A. “The Russia-Ukraine Conflict Laboratory: Observations Informing IAMD.” Military Review 104 (March 2, 2024): 22–31.

Shugart, Thomas. “Australia and the Growing Reach of China’s Military.” Lowy Institute for International Policy, 2021.https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep34851.

Suciu, Peter. “H-6: The Old Chinese Bomber That Has Transformed Into a Missile Truck.” The National Interest. The Center for the National Interest, November 22, 2023.https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/h-6-old-chinese-bomber-has-transformed-missile-truck-207438.

Tangredi, Sam J. “Anti-Access Strategies in the Pacific: The United States and China.” The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters 49, no. 1 (March 1, 2019).https://doi.org/10.55540/0031-1723.2859.

———. “ANTIACCESS WARFARE AS STRATEGY: From Campaign Analyses to Assessment of Extrinsic Events.” Naval War College Review 71, no. 1 (2018): 33–52.

United States Marine Corps. A Concept for Stand-in Forces. USMC, 2021.

———. Warfighting. Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication (MCDP) 1. Washington, DC: USMC, 1997.

VCDF Group - Military Strategic Plans. APEX, Integrated Campaigning for Deterrence. 2nd ed. Joint Concepts, 2024.

Vine, SQNLDR Robert. “Missile Defence: More Than Hitting a Bullet with a Bullet - Robert Vine.” Williams Foundation, October 11, 2020.https://www.williamsfoundation.org.au/post/missile-defence-more-than-hitting-a-bullet-with-a-bullet-robert-vine.

Wertheim, Eric. “Type 055 Renhai-Class Cruiser: China’s Premier Surface Combatant.” U.S. Naval Institute - Proceedings 149/3/1441 (March 2023).https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/march/type-055-renhai-class-cruiser-chinas-premier-surface-combatant.

Zeman, Phil. “Social Antiaccess / Area-Denial (Social A2 / AD).” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 12, no. 1 (May 28, 2021): 149–64.https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20211201007.

1 Missile Defense Project, “Missiles of China,” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 12, 2021,https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/china/.

2 Calculations by the author assume weapons with a range of less than 1000km cover an arc of 180°, while weapons with a range of up to 3000km cover 90°.

3 Calculations by the author assume weapons with a range of less than 1000km cover an arc of 180°, while weapons with a range of up to 5500km cover 45°.

4 Paul van Hooft, Nora Nijboer, and Tim Sweijs, Raising the Costs of Access : Active Denial Strategies by Small and Middle Powers against Revisionist Aggression (Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, January 1, 2021), 7–8.

5 Missile Defense Project, “Missiles of China.”

6 Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. Michael Howard and Peter Paret, First paperback printing (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1989), 357–78.

7 “ODIN - OE Data Integration Network,” accessed September 11, 2024,https://odin.tradoc.army.mil/WEG/; Thomas Shugart, Australia and the Growing Reach of China’s Military (Lowy Institute for International Policy, 2021), 10,https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep34851.

Defence Mastery

Contested Access and Manoeuvre: Part 3 © 2025 by . This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.