Introduction

Operation POSTERN was a joint forcible entry operation in New Guinea, 1943, spearheaded by land forces from the Australian I Corps. A truly joint and combined operation, POSTERN involved all three Services and forces from Australia and the United States. A retrospective glance at POSTERN affords valuable insights for future maritime campaigning. For the foreseeable future, the core military problem for amphibious and littoral operational planners is likely to remain gaining access to maritime terrain across multiple contested domains, and generating sufficient combat power ashore to stage at or seize advance bases. Operation POSTERN offers important operational lessons in theatre-shaping, deception, manoeuvre, and advance basing.

Background

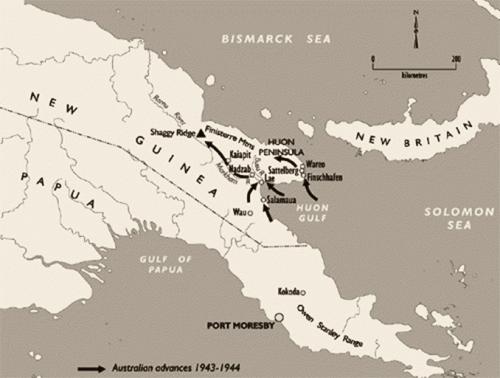

Operation POSTERN was a seaborne lodgment, air-landing, and airborne assault at Lae, New Guinea, in September 1943 that led to the Markham Valley and Huon Peninsula Campaigns of 1943–44. It was one of thirteen subordinate operations to CARTWHEEL, General Douglas MacArthur’s broader strategy to isolate the large Japanese naval station in Rabaul. POSTERN saw a predominately Australian land force, supported by Allied sea- and airpower, clear elements of the Japanese Eighteenth Army from the Huon Gulf and Peninsula. It concluded with the capture of the Japanese advance base and Army headquarters at Madang.

POSTERN and the capture of Lae were critical to CARTWHEEL’s success. They secured control of the Vitiaz and Dampier Straits separating New Guinea and New Britain and enabled subsequent operations across the theatre. Securing this critical maritime terrain set the conditions for the Dutch New Guinea campaign and the northward advance to the Philippines and mainland Japan.[1]

Before MacArthur’s leap into Hollandia, however, the Japanese needed to be defeated in eastern New Guinea. Following the loss of the Papuan beaches in 1942, the Japanese consolidated a defensive line at Salamaua, Lae, and Finschhafen. In January 1943, to buy operational depth, the Japanese attempted to destroy the small Australian garrison at Wau but were repulsed by Brigadier Murray Moten’s 17th Brigade and Kanga Force. The remainder of 1943 until POSTERN saw the Japanese garrison at Salamaua increasingly threatened and encircled by Allied force-flow into the advance base at Wau.[2]

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea proved decisive. In March 1943, the Japanese attempted to reinforce their Lae and Salamaua bases by sea from Rabaul, but the naval task force was detected in the Bismarck Sea by Allied aircraft. Several Japanese transports, merchant ships, and destroyers were sunk. A third of the Japanese personnel were casualties—significantly, 2,450 of these were intended army and marine reinforcements. Thousands of tons of provisions, ammunition, artillery pieces, and aviation fuel were also lost. Following the battle, the Japanese were forced to resupply via submarines, mostly at night, and were continually harried by Allied aircraft and naval vessels that enjoyed local air superiority and sea control.[3]

Figure 1: Australian Advances, New Guinea 1943-44

Map produced by Keith Mitchell, courtesy of the Australian War Memorial[4]

Operation POSTERN was preceded by three near-simultaneous amphibious operations in the South-West Pacific Area (SWPA) and South Pacific Area (SOPAC) in late June 1943. They included New Georgia in the Solomon Islands (Operation TOENAILS), Woodlark and Kiriwina Islands (Operation CHRONICLE), and Nassau Bay—south of the Salamaua-Lae area. In July, the Australian 3rd Division attacked Japanese defences around Salamaua by advancing overland from Wau. These operations set the theatre for the capture of Lae by diverting Japanese joint resources, providing additional airfields and naval advance bases (while denying them to the Japanese), and offering important experience in amphibious landings.

The opening phase of POSTERN, the capture of Lae, envisioned a double envelopment of the strategically important Japanese base at the mouth of the Markham River by the Australian I Corps. The plan called for the projection of forces into New Guinea from the air, sea, and land. POSTERN was a truly joint (all three Services) and combined (Australian and US) campaign that included the amphibious landing of a division, a regimental parachute drop, and the air-landing of two infantry brigades.[5]

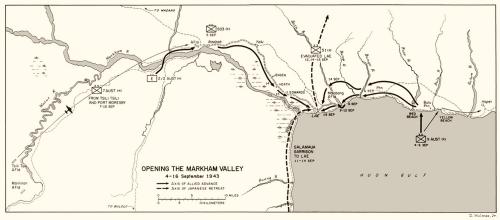

POSTERN commenced on 4 September when the Australian 9th Division landed unopposed at Red and Yellow Beaches, east of Lae. They were put ashore by Vice Admiral Daniel Barbey’s (US Navy) VII Amphibious Force. The following day, the US 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) and gunners from the Australian 2nd/4th Field Regiment with their 25-pounders, parachuted onto Nadzab airfield, west of Lae.

The Australian 7th Division air-landed at Nadzab over subsequent days with the objective of preventing Japanese withdrawal into the Markham Valley. By 15 September, the 7th and 9th Divisions had entered Lae and linked up. Despite fierce fighting, Lae was secured at a lower cost than anticipated. However, survivors of the Japanese 51st Division escaped through the Saruwaged Range, necessitating a series of amphibious end runs and the ensuing Huon Peninsula campaign.[6] Despite its distance in time and memory, Operation POSTERN offers valuable insights for future amphibious campaign planners.

Figure 2: Opening the Markham Valley, 4-16 September 1943[7]

Operational Lessons

1. “Setting” the theatre is critical for success.

Because of overall force parity, POSTERN was dependent upon local air superiority and sea control. The decision to air-land the 7th Division at Nadzab, use a parachute regiment to secure the landing strip, and supply a Corps-sized force via an air bridge, was predicated on gaining air superiority over the operational area. POSTERN was delayed from August to September to await the increased allocation of air assets to SWPA. In July, two further US fighter groups and a medium bomber group arrived in Papua. This complemented the arrival of the 380th Heavy Bombardment Group, which commenced operating from Darwin.[8]

The primary threats to POSTERN were the Japanese aircraft based at Wewak, further northwest along the coast, which had been moved forward from Rabaul to counter Allied progress in New Guinea. The additional aircraft were meant to relieve pressure on the Japanese advance base at Salamaua and to support naval resupply. To counter this predicament, General George Kenney, Commander Allied Air Forces SWPA, established a secret airstrip in Japanese-held territory in the Markham Valley, 100km east of Lae, to range Wewak.

On 17 August, Kenney’s B-25s, P-38s and Royal Australian Air Force Spitfires attacked Wewak, destroying over half of the 250 Japanese planes on the ground. The Japanese were compelled to withdraw from defensive positions outlying Salamaua but retained enough air power to contest the skies for local air superiority over key locations.[9]

Kiriwina and Woodlark Islands, some 500km South of Rabaul, were occupied as part of Operation CHRONICLE, in part so that P-38 Lightning Squadrons could be within striking distance of the Japanese base. They supported the critical phases of POSTERN.

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea denied reinforcement of Lieutenant General Nakano Hidemitsu’s 51st Division from Rabaul in early March. Of the nearly 7,000 troops aboard the convoy, less than 1000 made it to Lae. These troops were desperately needed, as heavy attrition through fighting and illness had depleted the Japanese New Guinea bases. Apart from denuding ground defences, the Battle of the Bismarck Sea had given the Allies overmatch amounting to local sea control.[10] These various shaping activities were necessary to set the theatre for POSTERN’s execution.

Figure 3: Australian 9th Division soldiers disembark from US Landing Ships, Tank (LST) at Red Beach

courtesy of the Australian War Memorial [11]

2. In joint forcible entry operations (JFEO) where opposing forces are close to parity, deception and manoeuvre are essential.

The various amphibious, air, and overland operations that preceded POSTERN were designed to degrade Japanese combat power, divert increasingly scarce joint resources and effects, and create windows of local sea and air control for Allied exploitation.

Salamaua was not an objective in itself—it was a diversion. General Sir Thomas Blamey, Commander Allied Land Forces SWPA, intended the Australian 3rd and 5th Division operations from Wau against Salamaua to act as a ‘cloak’ for operations against Lae, and as a ‘magnet’, drawing reinforcements away. Salamaua was not to be captured before the amphibious assault on Lae. The ‘Salamaua Magnet’ indeed thinned the more important Japanese garrison at Lae, as Japanese commanders stubbornly diverted precious resources south.[12] By the time of the Allied invasion in September, Lae’s defence relied on fewer than 10 000 combat and non-combat troops—a force too small to withstand the assault.[13]

Apart from establishing a coastal advance base, the Nassau Bay landings by Colonel Archibald MacKechnie’s US 162nd Regiment in late June added to the Japanese Eighteenth Army’s potential confusion. Occurring at the same time as TOENAILS and CHRONICLE, the Nassau Bay operation was intended to deceive the Japanese into believing that the Allied target was Salamaua because of the massing of firepower there, when the real objective was Lae.[14] The Nadzab airborne drop was planned to generate an operational dilemma for the Japanese, denying withdrawal routes into the Markham Valley, preventing overland reinforcements to Lae, and enabling hasty force-flow and build-up of combat power.[15] Deception planning and operational manoeuvre proved critical to POSTERN’s success.

Figure 4: 503rd PIR, Airdrop at Nadzab, 5th September 1943[16]

3. In a contested environment, inter- and intra-theatre movement is difficult and advance bases are necessary.

Securing advance naval and air bases allows the projection of airpower, the protection of shipping, reception and staging areas for future operations, and supply depots.

The Nassau Bay operation was conceived in part to relieve the Australian troops fighting overland toward Salamaua from Wau. When Major General Edward Milford’s 5th Division HQ took over from the Major General Stanley Savige’s 3rd Division in late August, one of the first priorities was to open a supply line with the coast. This shortened the overland supply route and reduced the demand for aircraft that were needed at Lae.[17] Flights into Wau were acceptable, but cargo had to be carried over mountains and ridges and through jungle and rivers to forward outposts. Opening Nassau Bay accelerated the process and allowed the Allies to concentrate greater combat power.[18]

Advance bases enable the extension of a weapon engagement zone (WEZ). The amphibious landings at Woodlark and Kiriwina Islands, both 160 kilometres from New Guinea, offered the possibility of building airfields to support short-range fighters to escort heavy bombers heading to Rabaul.[19] Kenney’s secret airfield at Tsili Tsili fulfilled a similar function against the Japanese base at Wewak. The numerous advance bases were essential prerequisites to enable the POSTERN operation.

Future Amphibious Campaigning

Future maritime campaigning and amphibious operations are likely to remain defined by their difficulty in gaining access across multiple contested domains. Emerging United States Marine Corps (USMC) concepts and doctrine on the employment of Stand-In Forces (SIF) assumes in part this problem can be solved through persistent access. Conceptually, gaining access is not the functional problem, because access should be maintained.[20]

SIF are envisaged to operate at the ‘forward edge of a partnered maritime defence-in-depth that denies the adversary freedom of action’.[21] In peer competition, however, power projection works both ways. The Japanese offensives in 1941-42 established an extensive maritime defence-in-depth that required years of campaigning to roll back. This campaigning necessarily began at the peripheral edges of the defensive zone, not within it. In any case, the opening Japanese offensives decisively neutralised numerous ‘Stand-In Forces’ in the Philippines, Singapore, Guam, Rabaul, and elsewhere. Prudent maritime campaign planning should not assume ‘persistence’.

Following the failure to seize Port Moresby and the loss of Buna and Gona in 1942, the Imperial Japanese Navy still retained a formidable layered series of advance bases. Salamaua, Lae, Finschhafen, and the Solomon Islands were designed to protect Rabaul by over-extending the WEZ of Allied aircraft. Rabaul, in turn, created standoff for the larger base at Truk, which was itself a projection of military power from the home islands.

SIF may prove formidable where partnered access exists. However, the complex diplomacy of the Indo-Pacific does not neatly lend itself to high-confidence assumptions about advance base access. The 2022 China-Solomon Islands Security Pact, for example, raises questions about the possibility of a more activist China potentially willing to extend military support to other states in its own search for partners. For pragmatic and principled reasons, China has hitherto eschewed direct security assistance, but deepening ties with Indo-Pacific states nonetheless complicates Western base access.[22]

Operations POSTERN and CARTWHEEL highlight that maritime campaigning is ultimately about such access—gaining, protecting, or denying it. Certainly, military technology has changed since 1943. Space-enabled surveillance, advanced sensors, and missile technologies have fundamentally changed the character of war at the tactical level. Nuclear weapons have altered the strategic decision-making calculus for policymakers and heads of state. But at the operational level, there is arguably greater continuity than change.[23] Cruise and ballistic missiles deliver ordinance and effects that were heretofore possible only by manned airframes. But missile launch sites remain as necessary as airfields, and advance bases require ground forces for their capture and protection. Air and sea control remain essential theatre prerequisites.

General MacArthur’s approach to CARTWHEEL differed from the ‘island-hopping’ campaign experienced in the Central Pacific, where vast distances necessitated repeated costly offensives. SWPA afforded the opportunity for ‘leapfrogging’ and isolation of powerful Japanese strongholds. MacArthur emphatically demonstrated this through his leap into Hollandia and the 1944 Western New Guinea campaign. For those objectives that could not be avoided, extensive shaping was necessary.

Operation POSTERN was an example of deception, manoeuvre, and shaping at the theatre level. Where the luxury of a SIF does not exist at the outset of hostilities, a WEZ requires gradual expansion through offensive maritime operations and seizure of ‘peripheral’ advance bases.

Despite the ever-evolving advances in military technology, future amphibious operations are likely to encounter operational-level problems like those faced by the POSTERN planners. The war in New Guinea was effectively about securing bases. Securing bases led to access. Access enabled the generation of combat power, domain overmatch, and ‘theatre setting’ to secure further bases and victory.

Dean, Peter. Australia 1943: The Liberation of New Guinea. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Dean, Peter. MacArthur’s Coalition: US and Australian Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, 1942-1945. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2018.

Dexter, Dexter. Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Vol VI: The New Guinea Offensives. Official History, Series 1: Army. Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1961.

Duffy, James. War at the End of the World: Douglas MacArthur and the Forgotten Fight for New Guinea 1942-1945. New York: Penguin Random House, 2016.

Erdelatz, Scott. ‘Operation POSTERN and the Capture of Lae.’ Marine Corps Gazette. June 2019.

Kim, Patricia. Does the China-Solomon Islands security pact portend a more interventionist Beijing? Brookings Institute, 6 May 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2022/05/06/does-the-china-solomon-islands-security-pact-portend-a-more-interventionist-beijing/

McCarthy, Dudley. Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Vol V: South-West Pacific Area First Year: Kokoda to Wau. Official History, Series 1: Army. Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1963.

Miller, John. Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul. United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Washington DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1959.

Perry, Roland. The Fight for Australia. Sydney: Hatchette, 2014.

Stanley, Peter. ‘New Guinea Offensive.’ Wartime Magazine. Issue 23. Australian War Memorial. 1 June 2003.

United States Department of the Navy, United States Marine Corps, A Concept for Stand-In Forces. December 2021. https://www.hqmc.marines.mil/Portals/142/Users/183/35/4535/211201_A%20Concept%20for%20Stand-In%20Forces.pdf

1 Scott Erdelatz, ‘Operation POSTERN and the Capture of Lae,’ Marine Corps Gazette, (June 2019)

2 Dudley McCarthy, Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Vol V: South-West Pacific Area First Year: Kokoda to Wau, Official History, Series 1: Army, (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1963), 534-591

3 David Dexter, Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Vol VI: The New Guinea Offensives, Official History, Series 1: Army, (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1961), 26-27; Phillip Bradley, D-Day New Guinea, (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2019), 39

4 Peter Stanley, ‘New Guinea Offensive,’ Wartime Magazine, Issue 23, Australian War Memorial, 1 June 2003

5 Peter J. Dean, ‘From the Air, Sea, and Land: The Capture of Lae,’ in Australia 1943: The Liberation of New Guinea, ed. Peter J. Dean, (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 212; Phillip Bradley, D-Day New Guinea, xiv

6 Dexter, The New Guinea Offensives, 347-481

7 John Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific, (Washington DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1959), 204-205

8 Peter Dean, MacArthur’s Coalition: US and Australian Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, 1942-1945, (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2018), 298-299; Dean, ‘From the Air, Sea, and Land,’ 214-215

9 Roland Perry, The Fight for Australia, (Sydney: Hatchette, 2014), 364; and Dean, ‘From the Air, Sea, and Land, 215

10 Karl James, ‘The Salamaua Magnet,’ in Australia 1943: The Liberation of New Guinea, ed. Peter J. Dean, (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 193-194

11 Australian War Memorial Photographic Record, Accession Number 306542, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C260172

12 Dexter, The New Guinea Offensives, 285-325; and James, ‘The Salamaua Magnet,’ 195-197

13 James P. Duffy, War at the End of the World: Douglas MacArthur and the Forgotten Fight for New Guinea 1942-1945, (New York: Penguin Random House, 2016), 227

14 Duffy, War at the End of the World, 221-222

15 Dean, ‘From the Air, Sea, and Land,’ 214; Bradley, D-Day New Guinea, 126-127

16 Miller, Cartwheel, 209

17 So important was this task that Commander I Corps, Lieutenant General Edmund Herring, told Milford that Savige’s failure to secure a coastal supply route earlier had been the reason for the 3rd Division’s relief. See James, ‘The Salamaua Magnet,’ 204-205

18 Duffy, War at the End of the World, 220

19 Duffy, War at the End of the World, 219

20 Department of the Navy, United States Marine Corps, A Concept for Stand-In Forces, December 2021, 3

21 A Concept for Stand-In Forces, 4

22 Patricia Kim, Does the China-Solomon Islands security pact portend a more interventionist Beijing? Brookings Institute, 6 May 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2022/05/06/does-the-china-solomon-islands-security-pact-portend-a-more-interventionist-beijing/

23 There are several Service and international definitions of the ‘operational level’ of war. There is plenty of disagreement over whether it even exists, and if it does, whether it is useful. It is a debate worth having. But for the purpose of the POSTERN discussion, the author defines the ‘operational level’ as ‘the lowest level of warfighting in which all joint effects and capabilities are unified under a single theatre commander’.

Defence Mastery

Technical Mastery

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.