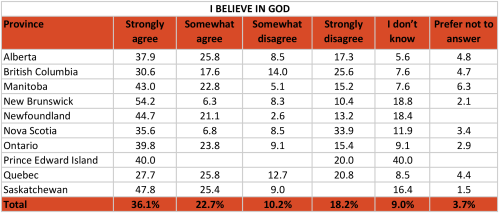

Recently the Formation Halifax team of chaplains in Halifax, Nova Scotia, held a professional development day to discuss emerging trends in Canada and their effects on whether, and how, the increasingly diverse and secular nature of Canadian society will affect chaplaincy to the Canadian Armed Forces in future years. In a presentation on emergent religious trends in Canada, Captain Peter Vere presented the following findings on atheism and agnosticism in Canada[1]:

Also, during this professional development we had access to an article written by Colonel Phillip Hoglin, CSC[2] that discusses the evidence of increasing atheism and agnosticism in the Australian Defence Forces (ADF), as well as a growing embrace of other non-traditional religions, which will likely continue to increase in post-Christian societies in the decades ahead. According to the author, it is logical to assume that Western democratic nations’ armed forces will see a marked increase in recruitment from amongst those populations. In Canada, the Canadian Armed Forces’ Interfaith Committee on Canadian Military Chaplaincy (ICCMC)[3] is in discussion on whether or not to include humanist chaplains in their fold. This discussion is not unique to the Canadian Armed Forces.

Colonel Hoglin has written a cogent article, entitled ‘Losing Our Religion: The ADF’s Chaplaincy Dilemma’, on the need for secularism in the modern Australian Army. In this article he writes:

Slowly and progressively over the last decade, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) has become less religious. Although religion, particularly Christianity, is a part of many military customs and traditions and was once a routine part of ship and barracks life, the connection that Defence members have to any faith has decreased to a level where the majority of officers, sailors, soldiers and aviators are not affiliated with any religion.

Since religion does not play the significant role in the lives of Australia’s military personnel that it once did, the ADF can now take active and deliberate steps to transition toward a genuinely secular, diverse and inclusive organisation.’[4]

Essentially, this article argues for the provision of ‘a secular pastoral care model for the ADF’, which would include Christian, non-Christian and secular support resources.[5] Our purpose is to respond to the arguments of this article, since it raises issues salient to Western militaries and their corresponding chaplaincies, including that of the Canadian Armed Forces and the Royal Canadian Chaplain Service.[6]

Colonel Hoglin rightly notes that current religious practices in the ADF are still exclusively Christian in orientation, and are not very inclusive in nature. Modern militaries need to represent and care for the populations they serve to protect, and every attempt should be made to diversify their chaplaincies accordingly. We agree with this basic assertion, but take issue with several misunderstandings on the nature of religion in general, and the role of chaplains in particular, in this thoughtful article.

Firstly, it is helpful to define the role of a chaplain, since chaplains are used in specific contexts.

We may define a chaplain as a cleric or lay person who represents a particular religious or philosophical tradition, and who is attached to a secular institution. Those secular institutions may be a military, a prison, a hospital, a fire or police department, a school or a university. That is to say that a chaplain usually works in a public institution representing a private tradition (although private companies do also hire chaplains to help employees with their issues so that they may ultimately be more productive and happy at work).

Secondly, looking at these secular institutions, it becomes evident that the people who are living and working in them are not always entirely free to practice their particular religion outside of the institution. For example, a soldier deployed in a foreign country still possesses the right to practice his or her own religion, but is unlikely to have ready access to a mosque, temple, synagogue or church. In Canada, this right is described in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and other legislation. In fact, Queen’s Regulations and Orders 33.06 makes clear that the CAF has an obligation, moral and legal, to provide religious services for the spiritual resiliency of their employees. It specifically states:

33.06 - RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL AND MORAL WELLBEING

Commanding officers and officers commanding commands or formations shall provide for the religious, spiritual and moral wellbeing of the officers and non-commissioned members under their command and the families of those officers and non-commissioned members.[7]

The CAF officers assigned to facilitate this religious, spiritual and moral wellbeing are military chaplains. Furthermore, based on this keystone policy directive, the Royal Canadian Chaplain Service (RCChS) has stated in its ‘Strategic Plan’ that chaplains are mandated to care for all military personnel and their families, regardless of where they stand on matters of faith or conscience.[8]

According to the official website of the Canadian Government: ‘The Royal Canadian Chaplain Service (RCChS) contributes to the operational effectiveness of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) by supporting the moral and spiritual wellbeing of military personnel and their families – domestically and internationally’.[9] Moreover, ‘CAF chaplains attend to the needs of all members of the CAF and their families, whether they identify with particular Faith tradition, have no specific spiritual/faith practice, belief or custom, or are spiritually curious’.[10]

Thirdly, a chaplain employed by a specific institution serves in a public-sphere organisation and, in serving any or all members of that organisation, is often called upon to work outside of his or her own tradition. Consequently, the RCChS has a formation tool called Canadian Forces Chaplain School and Centre (CFChSC) which trains chaplains professionally to be able to navigate pastoral ministry in both their own religious milieu (private sphere) as well as that of others (public sphere) with integrity. The official website describes the role of this school as one that ‘professionally trains chaplains as one cadre of all faith groups, preparing them to: serve the religious and spiritual needs of members of the Canadian Armed Forces; train CAF members in spiritual, ethical and moral resilience; support the mission of the CAF domestically and internationally; share their chaplain expertise internationally in support of the mission of the Royal Canadian Chaplain Service (RCChS)”[11]

Returning to Colonel Hoglin’s article, we now assess his discussion of the merits of a secular pastoral care model, suggesting that there are other models of chaplaincy which might be considered, such as that of the CAF,.

Colonel Hoglin asserts the merits of a secular pastoral care model for the ADF in regards to:

Diversity and Respect, since he contends: ‘Religion remains a well-documented source of cultural division’.[12] This is not entirely the case, nor is it an accurate understanding of religion’s complex role in a given culture. Indeed, religion can play an important role in matters relating to diversity and respect if handled with care and the right actors are invited to participate. The Canadian Armed Forces has instituted Religious Leader Engagement (RLE) Doctrine in its use of CAF chaplains because religion is part of cultural divisions in its area of operations, but can also be a very powerful tool in healing divisions, rifts and animosity amongst populations. It envisions chaplains as part of an overall comprehensive approach to peace building. It asserts:

- There is a tendency in the West to view the separation of politics and religion as ideal. However, it is apparent that for much of the world politics and religion are not separate, and further, that Western militaries ignore religious issues and agencies in an area of operation (AO) at the risk of overall operational effectiveness. [13]

- By virtue of their vocational training and credentialed religious identity, CAF chaplains are uniquely situated and qualified to initiate and conduct liaisons and engagements with religious leaders in an AO.

- The comprehensive approach is an overall global trend within international forces which intentionally utilises every resource including defence, diplomacy, development and commerce in a coordinated fashion to respond to domestic and international emergencies, wage war, resolve conflict and engage in peace build-ing. Religious leader engagement (RLE) is the means that ensures that chaplains are fully and uniquely integrated within the comprehensive approach. [14]

The fundamentalist nature of much secular thought, and its propensity towards political ideology, has caused more conflict and more killing than any religiously-sponsored state activities in history.

Colonel Hoglin also asserts that the ADF’s recent common values statement (October 2020) is based on, ‘the “humanity of character to value others and treat them with dignity”, 8 which is a fundamentally secular description of respect’. We see no fundamental secular nature in treating people with dignity, since most of the major religious traditions espouse the dignity of the human person, but for theological reasons, rather than humanist or natural ones. We see no conflict here between religious and secular values of dignifying humans with respect, but acknowledge that the reasons for doing so are essentially different.

Killing and the military. Hoglin states: ‘There is an age-old philosophical conflict between religious views on killing and the role of military forces in warfighting’.[15] He argues that a purely secular-minded stance on killing would alleviate cognitive dissonance. One question might well be asked: should members of a military be alleviated from matters of conscience, since ‘Just War’ theory asks soldiers to conduct violence in a controlled and commensurate manner, according to preconceived ethical precepts of what constitutes the just use of controlled violence? The chaplain’s role in conflict is not the conduct or encouragement of violence, but ethical considerations of conflict and in mitigating the worst effects of such conflict on military personnel themselves, on the families they leave behind and the society in which war is conducted.[16]

Operational bias. Hoglin argues that: ‘Religion may be a key divisive factor in any conflict or peacekeeping operation…’[17], a statement that needs qualifying and contextualisation before it can be accurately and adequately assessed as truthful, or the whole truth. As stated in a book entitled War, Peace & God: An Ethical Approach[18]: “Wars on religion are nonexistent. Religion is, however, present in all wars’. In fact, religion is a more or less important factor in any culture. But as already stated by us in this article, secular wars have killed a lot more human beings, animals and have had a much more devastating effect environmentally. Racism, political power, economic power etc. represent the real reason why states and non-state organisations go to war. Bolshevism, Nazism, totalitarianism and authoritarianism all provided far more compelling reasons to go to war than religion.

In Australia, all government departments are theoretically secular. In Canada, while the religious affiliation of Defence members has been decreasing (commensurate with the general population at large), the number of chaplains has steadily increased in both proportional and real terms. In Canada we have faced exactly the same situation as the ADF. The question that we have to answer is, why is this occurring?

The first answer might well be ‘unity in command’. Because CAF military chaplains are fully neutral in relation to the chain of command, they are able to provide insights from top to bottom and bottom to top on matters spiritual, religious, social and moral. This is vitally important, since commanders must remain aware of what is going on with their people. The second answer might be the fact that Canadian chaplains are highly trained in ethics. In fact, because chaplains are privileged with a specific status in a unit as an ethics subject matter expert, they are valued advisers, enjoying a freedom to ‘speak truth to power’ to the chain of command in a manner which might cause other officers to sacrifice their career. Nonetheless, despite this role as adviser on public-sphere aspects and issues of ethics and morale, chaplains mostly work more in private-sphere ethics with individual soldiers, sailors and air force personnel, helping them to make informed choices and make improvements in lifestyle. The third answer might be due to the most significant role of the chaplain, which is to guide the service member’s development, enrichment and growth in the spiritual domain; a role for which chaplains are uniquely trained and qualified.[19]

Lastly, CAF chaplains are trained in Mental Health resiliency to varying degrees and certain specialist chaplains possess a Masters degree in Clinical Pastoral Training which qualifies them to serve as Mental Health experts, working with multidisciplinary teams of therapists in certain military hospitals across the country. This specialisation allows trained chaplains to facilitate healing of spiritual issues, such as moral injury, guilt, grief, etc. Pastoral counselling courses are also taught at the CFChSC which allows deployed chaplains to play a critical support and triage role in the field and while soldiers are in operations. Being in situ and understanding the context, the chaplain is often the first care-giver available and able to intervene in a critical incident (such as a serious injury or death of a comrade) before a member has access to a mental health specialist.[20]

You will find enclosed a more exhaustive article on this topic.[21]

Targeting of ADF members. A non-secular military may provide an adversary that has a different religious view with a theological reason to target ADF personnel. A secular military may remove a source of difference that is based on religious fundamentalist grounds. Alternatively, notwithstanding religious differences, it is interesting to note that the spiritual dimension is now considered to be an important element of a full, healthy person. Even the World Health Organization includes this dimension in its Bangkok Charter, (2005). In Canada, we now have specialist chaplains in clinical pastoral counselling who work closely in a multidisciplinary health-care team in military hospitals, looking after the spiritual dimension of the ill and injured.

Enhancement of recruiting conservative perception of the ADF through overt religiosity may result in a view that the ADF is not representative of the population that it defends. In fact, in Canada it is the opposite. Most of the immigrants have a religious background and are often suspicious about secular institutions. The fact that their religion/spirituality is protected allows new Canadians to enrol in the CAF.

Wellbeing support triage. A notable advantage of secularism is that the wellbeing needs of ADF members can be assessed individually and assigned to professionals that are most appropriate based on need. The current religious chaplaincy model remains binary in execution, that is, a Defence member has the option to see a religious chaplain, or nobody at all.

As military chaplains, we fully support this last statement. In fact, most often a military member comes to a chaplain to explore questions in a context of confidentiality. Usually, what is said between the soldier and a chaplain remains confidential (unless it involves a question of harm to others or self-harm on the part of the soldier seeking help). Having stated this, there are occasions where a chaplain may have to refer the soldier to another, more appropriate, helping professional. However, it is essential that any private matter a soldier presents to a chaplain remains confidential (eg marriage counselling, a religious issue, etc.).

Our response to this thoughtful article by Colonel Hoglin does not answer all questions he raises, but is intended to raise awareness that other chaplaincy models, such as the Royal Canadian Chaplain Service, are sensitive to the new religious and spiritual diversities present in modern secular military service, which may well serve the ADF in meeting the religious, spiritual or secular needs of its soldiers.

[1] https://acs-aec.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ACS-Do-Canadians-Believe-in-God-EN.pdf, conducted by Association for Canadian Studies between May 3rd and may 7th 2019, and published in July 2019.

[2] https://theforge.defence.gov.au/publications/losing-our-religion-adfs-c…

[3] https://d2y1pz2y630308.cloudfront.net Specifically chap 4 that includes the role and the different religious denomination of this organisation

[4] Colonel Phillip Hoglin, CSC, ‘Losing Our Religion: The ADF’s Chaplaincy Dilemma’

[5] Ibid., Introduction

[6] https://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2833&context=etd This paper discuss the nature pluralistic of the Canadian Chaplain Services

[7] QR&O: Volume I - Chapter 33 Chaplain Services.

[8] RCChs’ Strategic Plan, ‘Called To Serve (2020-2030), pg. 8.

[9] https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/programs/royal-can…

[10] Ibid.

[11] https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/benefits-…

[12] Ibid., under Diversity and Respect.

[13] Y. Pichette & J.D. Marshall, ‘Questions of divine and International Law’, Canadian International Lawyer (CIL), Journal of the International Law Section of the Canadian Bar.

http://www.cba.org/Publications-Resources/CBA-Journals/Canadian-International-Lawyer

[14] Canadian Army Doctrine Note (CADN) 13-1, 24 July 201, pg. 1/11.

[15] Ibid., under Killing and Military

[16] Padre Yvon Pichette & Padre Derrick Marshall, ‘Is there a Role for Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) Chaplains in Ethics’, Canadian Military Journal, Vol 16, No 1, Winter 2015, pp 59-66

[17] Ibid., under Operational Bias

[18] L. M. Lanthier & Yvon Pichette, War, Peace and God: An Ethical Approach, La Pie Editions, 2016.

[19] Derrick Marshall & Yvon Pichette, ‘Spiritual Resiliency in the Canadian Armed Forces’, Canadian Military

[20] https://www.cafconnection.ca/National/Programs-Services/Mental-Health/M…

[21] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00592/full

Journal, Vol 16, No 1, Winter 2015, pp. 26-33

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.