The management of tempo is one of the elusive components of military victory. The most cited example is that of the invasion of France in 1940 when the tempo of German operations completely befuddled their opponents. The coalition led by the United States military produced their own version of tempo virtuosity in 1991 that had a similar effect on the Iraqi army. The success of both the Blitzkrieg and the ‘shock and awe’ of Desert Storm support the idea of conducting operations at a pace that cannot be handled by your opponent—setting the tempo of operational activity. However, while it is easy to see a tempo advantage in hindsight, the challenge remains how to train our personnel to understand and use the effects of operational tempo in the future. Unsurprisingly, the answer might be found in a simple commercial wargame.

On the surface, wargames are terrible at teaching military personnel about decision speed. Most have a chess-like appreciation of time where one side does all their activity and then another side does theirs. This results in a cycle of action and reaction that is rarely alterable by players during a game. However, tempo is not only about decision speed. The Australian Defence Glossary defines tempo as ‘the rate or rhythm of activity relative to the adversary, and incorporates the capacity of the force to transition from one operational posture to another’.[1] The idea of posture choice as a component of tempo is significant. Boyd’s Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (OODA) Loop[2] suggests that an observer of a situation orients to the problem by making some assumptions about what is likely to happen next. Based on the estimate of the situation, they make a choice about what to do—arguably a decision on posture. Finally, they implement the decision by acting.[3] Being faster than your opponent may be important in some situations, but only if you understand why you want to be faster. The result of your estimate of your opponent is critical. As suggested by the ADF definition, often the why of tempo is related to the posture of your force relative to your opponent’s situation.

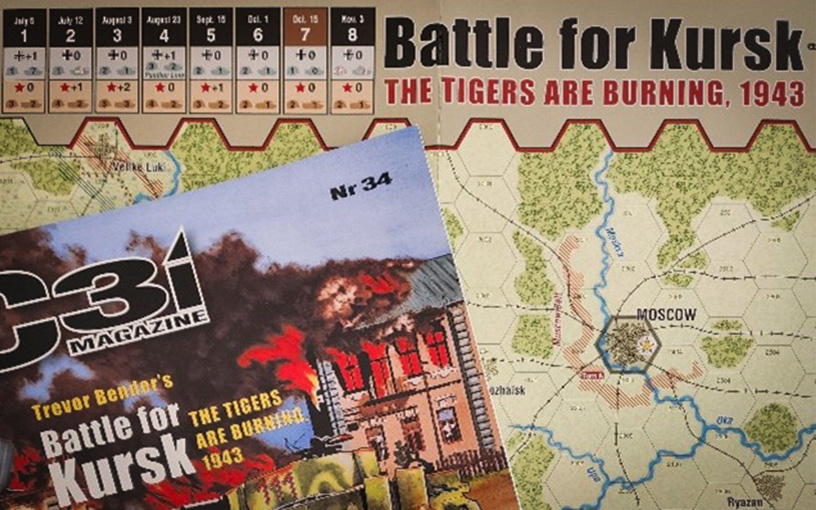

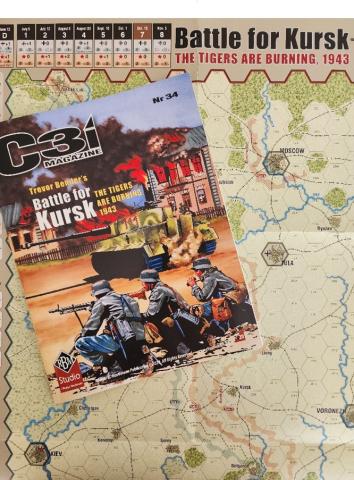

Unfortunately, the game-turn cycle that inhibits decision speed inadvertently dictates force posture as well. Players can often attack only in their turn. This creates a seesaw of tactical posture changes from attack to defence as the turn changes hands. A number of game designers have tried to alter this by randomising player actions, such as in the ‘Chit-Pull’[4] mechanism used in both wargames and Keno. However, this can often result in a player gaining a tempo advantage over their opponent by the luck of the draw rather than a conscious decision. Recently, the game designer Trevor Bender demonstrated his take on the importance of operational tempo in his game Battle for Kursk: The Tigers are Burning, 1943 published by RBM Studios in 2020.

The Battle of Kursk occurred in southwestern Russia during the summer of 1943 and was a major Soviet victory. Many authors believe that this battle marked a permanent transfer of the strategic initiative from Germany to Russia.[5] From this battle on, the German army had to husband resources and its commanders were forced to make increasingly critical decisions about posture changes across the Eastern Front. The Red Army had significantly more freedom of action, but it remained wary of the reduced, albeit still lethal, power of the German army when it switched to offensive operations. In the language of ADF doctrine, ‘the belligerent who can consistently maintain a higher tempo than their adversary tends to seize and retain the initiative. Initiative enables the holder to develop military actions on their terms’[6]—and this is exactly what happened at Kursk.

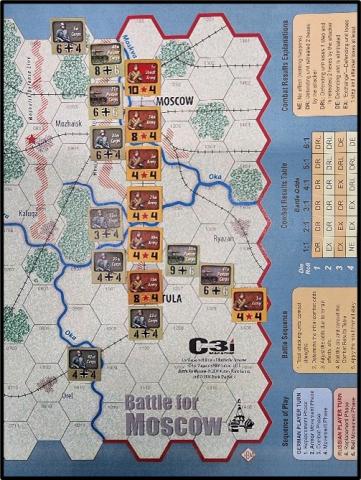

On the surface, the Battle for Kursk game is a faithful reproduction of the venerable Battle for Moscow game engine with alternate player turns, specialised unit movement phases, die rolling combat and zones of control on a hex-grid map. Both games seek to simplify the complexity of the operational level of war by aggregating data. Units represent corps or whole armies with all the complexity of such a formation placed into a generic attack or movement number. Where Battle for Kursk differs from others of its genre, however, is in the unusual addition of a Posture Selection Segment to the Sequence of Play.

At the start of a turn, both players secretly choose what their posture will be for that turn. When simultaneously revealed, the selection will determine what activities each side may perform and its impact on the arrival of vital Replacements used to rebuild depleted unit strength.

The posture options are:

| Posture | Replacement (or logistics) Effect | Play Turn Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Pause | +1 Infantry Replacement Point (Axis) +2 Infantry Replacement Point (Soviet) | Player may only execute the Replacements Phase for this turn. |

| Reposition | No change to scheduled replacements | Player may execute the Replacements phase and normal movement only (no armour or rail movement and no combat) this turn |

| Deploy | -1 Armour Replacement Point (Axis) -2 Armour Replacement Point (Soviet) | All phases except combat |

| Engage | -1 Infantry and Armour RP (Axis) -2 Infantry and Armour RP (Soviet) | All phases allowed |

The designer notes for the game state: ‘The overriding decision the players will have to make each turn is what Posture to choose. In most wargames, one automatically gets a movement and combat phase. Not so in this game – these must be purchased by expending would-be replacements to earn greater freedom of action … So, if you put the front in motion, there will be a cost. Total combat power across the line is weakened through movement, shattered by combat and restored by rest, replacements and training.’[7]

Here we have a game that presents two important learning outcomes for the military professional. Firstly, it forces the player to think about logistics before anything else. The posture selection mechanism is a choice between action and inaction to gain a logistic benefit. Arguably, this is at the heart of almost every operational level decision. Yes, you still get to do all the exciting tactical decision-making associated with games of this nature—where do I move my units to? What effects will the terrain have on combat? How do I build high-odds combat situations? etc, but it is also a genuine operational level experience because you are forced to think about what tempo means to your future logistic situation.

In making the posture selection decision you also have to assess your opponent’s options and consider what posture they might adopt given their situation. Therefore, you must select your tempo relative to your opponent, and this can be an agonising decision. As the designer suggests, the game makes you want to posture in the Pause mode every turn so you get those valuable extra replacements for your tired infantry, but the defence is no path to victory. The battles around Kursk were offensive operations for both sides and you have to order your forces to Engage to win, and engaging drains resources. Here the game reinforces ADF doctrine, which talks about the complexity of adopting a Pause posture: ‘Operational pauses are sometimes unavoidable at any level of command. Logistics demands, the desire to wait for more favourable circumstances, the need to reconstitute forces, or a shift in main effort may impose an operational pause. Such pauses are often necessary to avoid reaching a culminating point. However, operational pauses risk surrendering the initiative. They provide an opportunity for the adversary to also reorganise or exploit the pause. Therefore, operational pauses should be used when there is no alternative.’[8] Battle for Kursk allows the players to experience what ‘no alternative’ really means.

Although the game is a model of warfare, and all models are wrong, this could be a very useful simulation for military professionals to gain vicarious experience of operational tempo decision-making. The decision to change posture—in this game the pause, reposition, deploy, engage selection—against an opponent looking for an asymmetric advantage from their own management of tempo is critical to success at the operational level, and one the game addresses directly. The game can also be a lesson in history as it replays the precarious position of the German army in the summer of 1943 and can be used to discuss the elements that make this battle such an interesting historical case study. More importantly, however, the game makes explicit the player decisions around force posture and operational tempo that are worthy of conversations for planning teams and those interested in experiencing the operational art of war.

2 Alastair Luft, ‘The OODA Loop and the Half-Beat’, The Strategy Bridge, 17 March 2020. Accessed 12 June 2024.

3 Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1 – Warfighting (USMC 1997), 102 MCDP 1 > United States Marine Corps Flagship > Electronic Library Display (marines.mil)

4 The ‘chit-pull’ mechanism is where players randomly draw a counter that indicates which group of units or what actions can occur next. Like pulling random numbers from a bag in Keno, the chit-pull creates a fog-of-war aspect to game actions as well as enabling players to break the I-GO-YOU-GO cycle of normal game turns.

5 Heinz Guderian, Panzer Leader (Costa Mesa: Noontide Press, 1988), 302

6 ADF Doctrine Publication 5 – Planning, Edition 1, 2022, 60

7 Trevor Bender, ‘Battle for Kursk, 1943 – Rules of Play’, C3i Magazine Nr.34, (RBM Studio LLC, 2020), 13

8 ADF Doctrine Publication 5 – Planning, Edition 1, 2022, 61

Defence Mastery

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.