Implications and an Inevitable Evolution

Abstract

Over the last few decades the Australian Defence Force has started demonstrating the traits of a mainstream occupation, having progressively lost many of those traditionally associated with an institution. This article outlines the extent to which occupational traits now dominate over institutional traits and introduces the implications of this transition. The authors observe that the ADF may ultimately need to either fully embrace its identity as an occupation, continue with the rhetoric of an institution while displaying fewer of its characteristics, or make a deliberate attempt to reclaim the institutional traits that define the ADF as a unique employer. It is suggested that it may be too late to pivot back to an institution, but it is not too late to apply the most appropriate attributes to the right workforce segment.

In 1977, just four years after the United States transitioned its military toward an all-volunteer force, the eminent military sociologist, Charles Moskos, published his seminal piece on what is now referred to as the Institution/Occupational model, or I/O model.[1] In it he argues that the (US) military is changing from an institution to an occupation and contemplates the possible consequences, such as trade unionism, over-reliance on contract civilians, and deteriorating service morale and cohesion. In a similar vein, but from a workforce rather than an organisational perspective, Morris Janowitz and Allan Millet examined how military employment could shift from a profession to an occupation. They argued that such a transition threatened the operational effectiveness of the military and could result in the military prioritising its own interests over that of its nation.[2]

In this article we explore the likelihood that the ADF has shifted from an institution into an occupation and that military employment can no longer be easily defined as a profession. After a brief introduction to some of the theories of the I/O model, current characteristics of the Australian Defence Force personnel system are mapped to determine whether it reflects a dominance of institutional or occupational traits. Finally, the implications of the ADF residing in the institutional or occupational end of the spectrum are introduced in discussing whether either model is appropriate for the current or future strategic environment.

Decades of Change

When Moskos and Millet released their papers, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) was a year old, having been formed from the previous four separate federal departments of Defence, Navy, Army and Air Force in 1976.[3] The traditions, customs, processes and procedures of the new tri-service institution, including unified approaches to recruiting, promotion and training, were yet to take shape and continued to reflect the single-service nature of their origin for several more decades. The military workforce reflected the expectations of the Australian society of the time, being predominantly male, of Anglo-Saxon descent, and purportedly heterosexual. Military service was seen as a career, with precisely defined career pathways and rigid hierarchies, and the promise of a pension after 20 years of service. Salaries were not generous, but the Services took a paternal interest in their members, providing for most of their needs and establishing de facto communities in on-base ‘married patches’.

Almost half a century later there have been numerous changes. The Defence Force has evolved in line with Australian society, incorporating women’s auxiliary services into general service by the mid-1980s; lifting the ban on homosexuality in 1992; introducing a Total Workforce System to enable flexibility of service to meet personal circumstances; and increasingly reflecting the multicultural population of Australia.[4] In management practices, recruiting was consolidated across the three Services and outsourced in the early 2000s, the service housing model was contemporised in the late 1990s with the creation of the Defence Housing Authority, allowances were simplified and rolled into salary (and thus superannuation) where possible. In the most recent Defence Strategic Review, some of the final bastions of the previous single-Service-based approaches have been collapsed into common models, with career management now unified and establishment management consolidated.[5]

But more significantly, the role of the ADF has also changed. The Australian armed forces of the 1970s were focussed on the application of lethal force, either in declared wars or in counterinsurgency operations. In the 1980s and 1990s the strategic focus changed to lower-level contingencies and peacekeeping operations, whilst budget constraints forced economic efficiencies such as reduced military workforces and increased reliance on contracted support.[6] The demands for fiscal frugality continued throughout the 2000s and 2010s despite increasing commitments to warlike operations in the Middle East, whilst improved information management systems enabled closer monitoring of key performance indicators and the application of corporate management techniques. In recent years the challenging strategic environment has broadened the remit of the modern ADF to cover the full spectrum of competition as well as being increasingly called upon to assist domestically, either for natural disasters such as bushfires and floods, or contingencies such as COVID. Progressively, the changes that have occurred, especially over the last 30 years, suggest a demise or change in many of the attributes that would be associated with an institution.

Introduction to the I/O Model

Introduced in 1977, Moskos’ Institutional/Occupational (I/O) model has developed into an extensive body of literature that explores how the nature and structure of military organisations differ between Institutional and Occupational approaches depending on the motivations for service (calling versus benefits), identity (distinct group with shared values/beliefs versus people who happen to work together for a common purpose) and the way the organisation treats its members (paternalistic versus economic efficiency).[7] Moskos theorised that as Western societies developed, the organisations within them would become increasingly bureaucratic and corporatised. Changes in the reward system (remuneration) and various conditions of employment would increasingly reflect transactional approaches reminiscent of organisations providing an economic service or product rather than a societal benefit transcending self-interest.

From a workforce perspective, there is also a continuum from a profession to an occupation. A profession is characterised by highly skilled practitioners who strongly identify with their ‘calling’, adhere to a collective set of beliefs and values, are highly skilled, and share a commitment to high performance.[8] Don Snider and Gayle Watkins concur, noting that a professional model prioritises effectiveness and knowledge development, whereas an occupational model prioritises efficiency, using corporate management methodologies to incentivise desired behaviour. Snider and Watkins conclude that in volatile and complex environments, a professional model can more rapidly adapt to changing conditions and shape human behaviour, whether it be internally within the armed forces or externally through the application of lethal or coercive force.[9] Although Snider and Watkins argue that the US Army has increasingly applied occupational approaches that accentuate its bureaucratic nature to the detriment of its operational effectiveness, Janowitz contends that militaries are unlikely to become occupations due to the specialist knowledge required, which requires extensive training, and the strong shared identity that armed forces maintain.[10] Nonetheless, the continuum remains and armed forces, including the ADF, may reside at any point along it depending on the characteristics that the organisation and its people exhibit at any point in time.

The ADF on the I/O Continuum

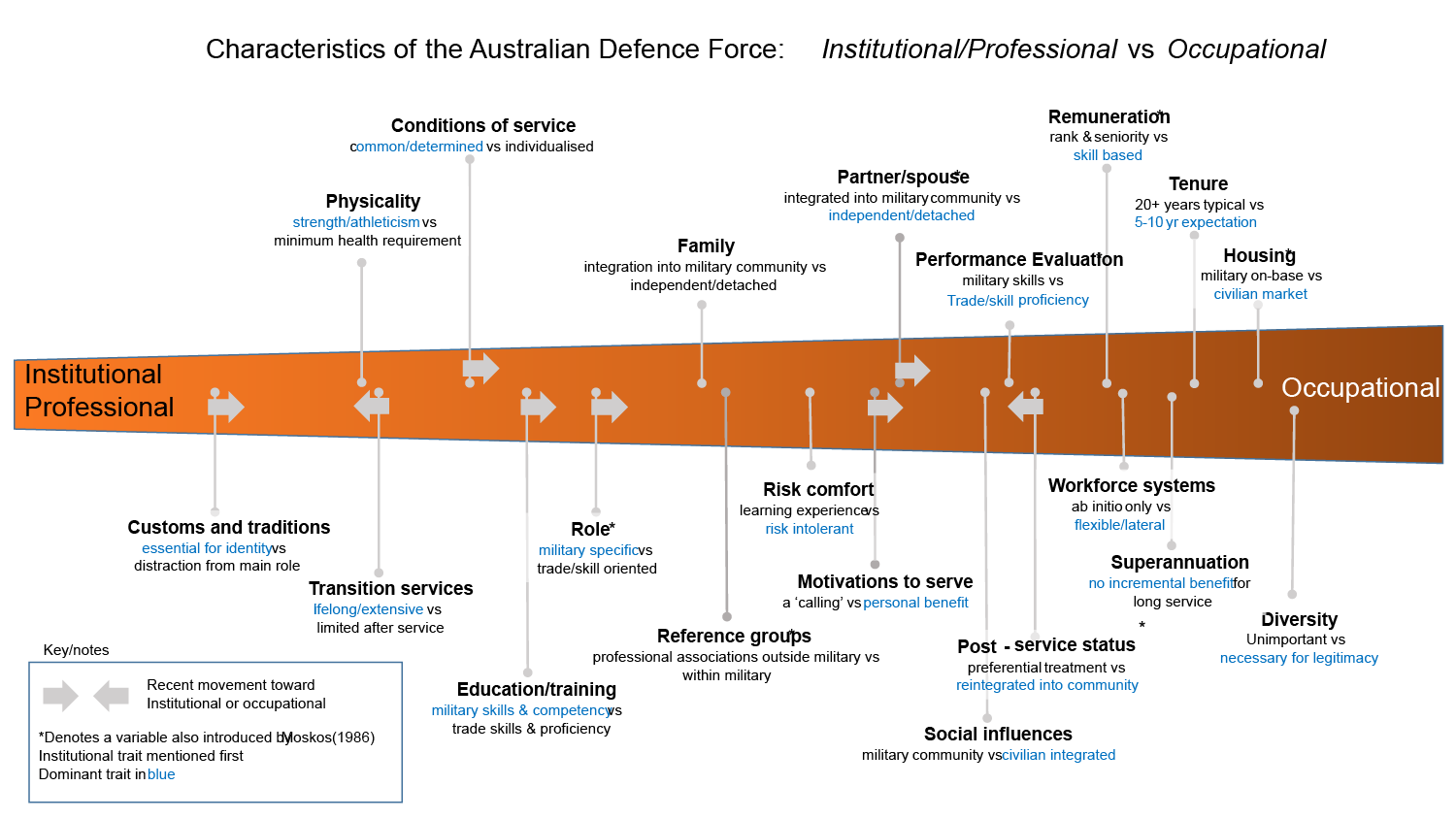

In his 1986 follow-up to the 1977 paper, Moskos presented a range of variables that are useful in helping to consider whether a military organisation can be considered an institution or occupation.[11] In figure 1, these variables are contemporised and updated for the current Australian context and shown on the spectrum of institutional/professional to occupation variables.

Figure 1. Characteristics of the Australian Defence Force: Institutional/Professional vs Occupational.

[12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31]

Implications of the ADF’s Evolution from an Institution to an Organisation

The skew of variables to the right of figure 1 shows that the ADF is well advanced in its evolution toward an occupation with only a few residual institutional traits. Some variables are returning to a paternalistic institutional model after a period of arguable neglect, such as support to transitioning members and the post-service status of veterans. The majority of variables, however, are either trending toward an occupation or have completely transitioned with little prospect of revision. On balance, while the ADF maintains some attributes of an institution/profession, these are diminishing and the ADF predominantly displays the characteristics of an organisation/occupation.

Despite the transition, the ADF as an occupation does not suit everyone and comes with inherent personnel and strategic risk. The occupational model competes within an open marketplace to attract and incentivise people by rewarding them for work performed, either routine service, arduous duties or on deployment. This approach can encourage mercenary-like behaviour by focusing on pro-self and extrinsic stimuli while undermining those who serve and deploy for intrinsic reasons. As a result, Defence members are placed within an occupational employment framework regardless of their personal motivations, weakening institutional/professional attributes such as the sense of ‘service’ and ‘calling’.

An occupational model would also restrict the ADF’s responsiveness to changing strategic environments. The ability to expand and mobilise for war becomes less assured the further the ADF drifts towards an occupation. While some limited skills and equipment may be able to be purchased or hired from the national support base, the rapid recruiting and training of thousands of additional personnel to perform risky and uncertain work becomes financially and socially prohibitive. The expectations of high-quality housing, comprehensive training, skills-based high salaries, shorter tenures and a complex employment value proposition created through an equally complex conditions-of-service package, creates an unsustainable and costly strain on Defence, Government and national resources, notwithstanding being unviable in periods of conflict. Significantly, high causalities in an ‘occupation’ would become harder for the public to rationalise against casualties in an ‘institution’, risking public sentiment and support for the military and its operations.

It is difficult to wind back the occupational traits of the ADF should the need arise, as these are now imbedded in law, policy, culture and expectation. The ADF is effectively stuck between its self-proclaimed identity as an institution, but with the characteristics of an organisation, and is now confronted with the uncomfortable decision of whether it should operate unreservedly as an occupation, or cling to what remains of its institutional identity. This leads to two broad options: a genuine and authentic embrace of occupational employment principles, or a deliberate attempt to reclaim institutional traits that define the ADF as a unique employer.

A formal shift to an occupation would see the ADF embrace a more corporate and competitive approach toward the provision of capability. This could see an employment value proposition emphasising competitive and economic approaches toward recruiting and retention, incentives, deployment opportunities, promotion, and career management. People capability would be viewed through the lens of a quantifiable product for ‘purchase’ with associated costs and return-on-investment. Matters such as national call-up, conscription, and national service would be politically untenable (as they arguably already are) and financially unviable if the same employment conditions were to be applied. Accordingly, people capability must also be subject to corporate approaches to optimisation including ‘sale’ (i.e. disposal of unrequired people capabilities), restructure, and outsourcing.

In contrast, reclaiming lost institutional traits, or reinvigorating those that remain, would require the ADF to distance itself from some of its more recent approaches to workforce management. Unless there is a demonstrable capability benefit, policies that favour the individual over the group would require dissolution, incentives would be oriented toward the collective, and career management would strictly favour the ‘service need’. National rhetoric and image may also need to change with emphasis on public display, creation of exclusive military communities, and wilful proclamation that ‘defence is different’ to ensure that that society’s standards do not apply in the same manner. However, there may be severe consequences for recruiting, retention and professional (non-military) skills development and social legitimacy in this approach that may ultimately compromise people capability anyway.

Arguably, neither of these two broad approaches addresses the complexity of the modern strategic environment and the ADF’s mission. An entirely occupational ‘work for hire’ force is unaffordable and subject to market supply and demand, but a pre-1980s style, fully professional force is also prohibitively expensive as some functions can be efficiently outsourced to provide a better capability outcome. A more sophisticated approach would be to recognise that the ADF has roles and functions that span the institutional/occupational spectrum and consciously structure the workforce and incentive system to exploit this variation.

A heterogeneous approach would see an empowered cadre of military professionals, driven by altruistic motivations, capable of adapting to and leveraging rapidly changing tactics and capabilities to ensure the ADF is fit-for-purpose. This cadre must be empowered to challenge norms, test alternatives and implement improvements to doctrine, force structure, and culture. Outside this cadre would sit a broader cohort of personnel who enjoy the sense of service but are motivated by the promise of pay, promotion or increased opportunities through professional development. In the event of mobilisation, the cadre would re-establish the institutional traits necessary for effective military service in the changed environment.

Whatever it decides, the ADF can’t continue to embrace some occupational traits while holding on to a handful of institutional ones. If it hasn’t already, this conceptual no-man’s-land will manifest into an ambiguity around what the ADF is, the purpose for which it recruits and retains individuals, and even the role of the ADF itself. Public sentiment will be unclear on whether the ADF exists ‘just in case’, or whether it exists ‘to do things’ for the country. At some point the ADF will need to decide where to rest on the institutional/occupational spectrum and introduce mechanisms to enable a change should it need to.

Conclusion

Discussions around a military as an institution or organisation are complex and can invoke passion in current and former serving members with lived experience through one or many of the ADF’s evolutions. Regardless, the ADF is well on its way to demonstrating the traits of an occupation, having progressively lost many of those associated with an institution. This observation requires that Defence either fully embrace its identity as an occupation, continue with the rhetoric of an institution while displaying fewer of its characteristics, or make a deliberate attempt to reclaim the institutional traits that define the ADF as a unique employer.

A genuine and authentic embrace of occupational employment principles presents several risks for Defence derived from a reduced ability to respond to changing strategic threats and an inability to adequately differentiate itself from the thousands of other occupations in Australia, but it is likely to be sustainable within the national employment market. Re-emphasising institutional traits will likely distance and isolate the ADF from its recruiting base and create retention uncertainty, thereby threatening workforce strength and ultimately defence capability, but may be more agile and responsive. Somewhere between these two ends of the I/O spectrum is an acknowledgement that there are differences in roles and people and that approaches should be varied to obtain the optimum capability outcome. Pragmatically, having already adopted many occupational traits, it may be too late to for the ADF to pivot back to an institution, but it is not too late to apply the most appropriate attributes to the right workforce segment.

1 Charles C. Moskos, ‘From Institution to Occupation: Trends in Military Organisation’, Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Fall 1977): 41-50.

2 Morris Janowitz, The Professional Soldier: A Social and Political Portrait (New York: Free Press, 2017), 5-7, 435-40; Allan R Millett, Military Professionalism and Officership in America (Columbus: Mershon Centre of the Ohio State University, 1977).

3 David Horner, Making the Australian Defence Force, ed. Peter Dennis and John Coates, The Australian Centenary History of Defence, (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2001), 44-49.

4 Horner, Making the Australian Defence Force, 324, 328-9.

5 Commonwealth of Australia, Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: AGPS, 2023).

6 Horner, Making the Australian Defence Force, 324, 328-9.

7 42-43.

8 Millett, Military Professionalism and Officership in America.

9 Don M. Snider and Gayle L. Watkins, 'The Future of Army Professionalism: A Need for Renewal and Redefinition', Parameters 30, no. 3 (2000): 6-7.

10 Snider and Watkins, 'The Future of Army Professionalism: A Need for Renewal and Redefinition', 6-7; Morris Janowitz, 'From Institutional to Occupational: The Need for Conceptual Continuity', Armed Forces & Society 4, no. 1 (1977): 52.

11 Charles C. Moskos, ‘Institutional/Occupational Trends in Armed Forces: An Update’, Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Spring 1986): 377-382.

12 Customs/traditions: Essential for maintenance of identity and esprit de corps in an institution but an unnecessary distraction from job role and primary defence purpose in an occupation. Many ADF traditions endure but often in a diminished capacity and only when they do not disrupt the training cycle.

13 Physicality: Athleticism is valued as a virtue. It is inherently recognised that members of a military organisation should be more physically developed than potential adversaries.

14 Transition services: an increasing focus on support to veterans is emerging. Employment support, veterans support groups, ex-service organisations and DVA are increasing resources to assist transitioned/transitioning members.

15 Conditions of service: conditions of service remain predominantly one-size-fit-all with some limited allowances for flexible work and other individualised approaches to workforce management.

16 Education/training: Ongoing development of combat, technical and professional mastery, through formal courses and individual study is emphasised with a balance between education related to profession-of-arms and job role.

17 Role: Primary functions are focussed on the spectrum of military contests and therefore are unique to Defence. However, Defence Aid to the Civil Community utilises military capabilities in civilian applications, often utilising Defence staff as unskilled labour.

18 Family: integration of family into military community through friendship groups and invitation to social events is dependent on unit-level initiatives and the culture around attendance. Individual family experiences will differ.

19 Reference groups: Professional reference groups within the military chain of command (‘vertical’) differs from external subject matter experts and regulatory authorities outside the military (‘horizontal’). Many non-combat job roles undertake external training and credentialing designed to maintain equivalency with civilian counterparts.

20 Risk profile: senior leadership champion risk-based decision making, however, organisational inertia, scrutiny, media and fear of consequences means there is a general risk intolerance.

21 Motivations: Motivations to join the ADF are more ambiguous than previously understood. Marketing campaigns have recently leveraged on self-interest attributes, and nationalistic reasons to enlist and serve have diminished.

22 Partner/spouse: ADF spouses/partners frequently pursue employment and individual pursuits outside of the military community. While they may be incorporated, informally or formally, as an integral part of the military community at times, they are also often removed or detached from the military community through own employment, individual pursuits or lack of commonality.

23 Social influence: Military social influence in major military areas remains active but in other locations the influence is minor and incidental.

24 Performance evaluation: segmented by rank, skill, trade and frequently quantitative. Values resource efficiency (cost, personnel, assets) and achievement of short-term metrics over longer-term organisational effectiveness.

25 Post-service status: while there is public recognition of service and some minor veterans benefits, former members are generally reintegrated into society with infrequent recognition of service.

26 Remuneration: based on an interaction between skills and experience (that can sometimes be reflected in rank). Primary remuneration placement is based on job role rather than rank and seniority as indicated in the Graduated Officer/OR Pay Scales.

27 Workforce systems: the total workforce system encourages a range of work patterns, movement between full-time and part-time service and re-engagement/re-enlistment reminiscent of a lateral occupational approach.

28 Superannuation: based on length of service in the organisation/occupation rather than reaching certain key milestones of service within the institution longevity.

29 Tenure of service: corporate rhetoric is focussed on long-term retention; however, remuneration structure, superannuation, transition programs, credentialing, and the realities of life expectancy/retirement are drivers toward shorter but impactful careers. Current ADF length of service is less than 10 years.

30 Housing: on-base accommodation is generally limited only to trainees or members in their first year of service after training. Outside of this, housing options are provided (by Defence Housing Australia) within the civilian community or members may seek private rentals.

31 Diversity: Homogeneity in the workforce is viewed as a legitimate approach to commonality in systems, equipment, procedures whereas diversity may be viewed as a distraction from the organisational purpose. In the ADF there is significant emphasis on diversity through specific recruiting and employment strategies aimed at diversifying the workforce toward representation.

Defence Mastery

Social Mastery

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.