Introduction

Australia is situated amongst a complex and chaotic strategic environment. The Indo-Pacific region is shifting away from the United States as the sole dominant power, and the primary focus now is the competition between China and the United States.[1] This competition among major powers in Australia's vicinity risks jeopardising national interests and creating a significant likelihood for conflict.[2] ‘For the first time in eighty years, Australia faces the prospect of major regional conflict that directly threatens our national interest.’[3] Further, grey zone warfare and multi-domain operation prevalence have surged with greater technological advances pushing the scalability of war. This creates uncertainty, yet: ‘War is in the realm of uncertainty; three-quarters of the factors on which action in war is based, wrapped in a fog of uncertainty.’[4] In light of Australia’s complex and uncertain strategic environment, planning stands as a crucial component in ensuring the success of military operations.

The term ‘plan’ implies a structured, institutionalised, and formal method for accomplishing a specific objective.[5] The Australian Defence Force (ADF) relies on the Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) as its primary tool for planning and decision making, offering concepts and theories that assist Soldiers and Officers in enhancing their problem-solving skills. [6] The foundational doctrine for contemporary military planning, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff Joint Publication 5-0, Joint Planning, commences with a quote from General Dwight D Eisenhower: ‘Plans are useless, but planning is indispensable’.[7] This concept underscores the importance of recognising that problems cannot be solved using the same thinking that created them.[8] The recent strategic setbacks experienced by military coalitions in Iraq and Afghanistan identify significant challenges in planning military campaigns, resulting in inefficacy and disarray.[9] Australia’s current operations are undertaken in complex and chaotic environments, demanding a planning tool that addresses these challenges.

This paper will argue that the ADF must place greater emphasis on non-linear thinking and its subsequent planning. It will be broken into three sections, with the first section exploring the linearity of JMAP.[10] The differences between linear and non-linear thinking will also be discussed, with linear thinking encouraging convergence amongst military planners.[11] The second section highlights that military planning needs to focus on thinking and decision making. Cillier's 1998 characteristics of complex systems substantiate the view that Australia's environment is complex[12]. The Cynefin Framework is recommended as a sense-making model to adopt initially as part of the scoping stage of the military planning process. It offers a non-linear thinking approach which will enhance planning. However, the ADF is not culturally ready for a complete replacement by a new paradigm or model. This leads to the final section which will outline the applicability to the ADF. It identifies the fact that training has traditionally focused on linear systems and pre-war education. Therefore, the ADF must teach personnel to understand the complexity of peace and conflict operations and concentrate on learning non-linear planning techniques.

The linear nature of military planning

Numerous influential authors and theorists share the perspective that war is a complex, non-linear phenomenon.[13] This means that there is volatility, uncertainty, and ambiguity in the midst of the strategic environment.[14] Australia is undergoing a period of ongoing contestation and escalation of tensions while confronting a wide range of potential threats.[15] The 2016 Defence White Paper (DWP) implied that no significant attack on our territory was likely over the next 20 years.[16] However, scarcely four years after the 2016 DWP, Australia's strategic circumstances substantially deteriorated, initiating a radical change to Australian Defence planning.[17] The critical point is that motive and intent can change quickly, complicating intelligence collection, analysis, and risk assessment tasks in military planning.

JMAP works well for tactical planning in a conventional setting; however, different tools must be utilised to address complex problems.[18] JMAP has functional elements with simple predefined objectives, and a large part of the plan is provided by superior Headquarters, where the intelligence flows from Headquarters to subordinate units.[19] This means that subjective assumptions are made at the initial stages of planning. Since the beginning of the 21st century in Iraq and Afghanistan, military operations have demonstrated the need for some subjective experience and naturalistic decision making to cope with chaos and complexity.[20] Further, our linear military planning has not been sufficient for all operations. The emergence of Islamic State in Iraq and the disastrous collapse of the coalition-trained Iraqi army in 2014 highlight the failure or significant deviation from the initial objectives in the ongoing campaigns of those two conflict zones.[21] Yet criticising military planning in retrospect is unfair. However, analysis of previous conflicts enhances learning and creates an improved planning process. As Ritzer argues: ‘If the planning concepts, cognitive processes, and ontological choices, the foundations for military planning are not analysed, it allows conditions for the next conflict failure to fester.’[22] In an ever-evolving and complex global landscape, adapting to a dynamic, flexible planning framework becomes imperative to ensure mission success.

In contrast, historically, military planners have followed a linear, known process.[23] They need to become ‘thinkers’ amid this complex and uncertain environment.[24] JMAP planners often find themselves obligated to utilise a linear causal approach and deconstruct campaign strategies by focusing on the lines of effort with centres of gravity, due to difficulty in conceiving an alternative method for tackling military issues. ‘Military planners also exhibit an “almost pathological desire to achieve certainty” in the notoriously uncertain environment of war, resulting in linear thinking and campaigning’.[25] ‘It is where the nineteenth-century military philosophies of Carl von Clausewitz [war will remain a contest of wills] and Antoine Henri Jomini [principles of war] still dominate our western collective military outlook.’[26] This teaches military planners to start JMAP by envisioning a desired future outcome and then establishing goals that resolve current military problems. It is a reverse analysis method structured around the centre of gravity, amongst other concepts.[27] There is navigation from the present to the proposed future state, and time and space can be controlled and reduced with causality and logic.

Additionally, JMAP does not adequately facilitate adaptation or the resolution of complex problems, both essential for modern operations.[28] JMAP is burdened by rigid linear protocols that don’t match natural thought processes.[29] It is also ‘not useful for contingency planning—the modern and future geopolitical environment is complex, is a changing and unpredictable web of interactions which cannot be approached in a linear, mechanistic manner by a universal planning methodology’. [30] In contrast, Colin Gray argues that, ‘Defence planning cannot be adaptable as boundary-free values because it comes at a cost and resources are always bounded.’[31] However, ‘Given that error-free defence planning is never an option, anywhere at any time, the practical challenge is to provide necessary adaptability.’[32] David Walker argues that decision making is instinctive without distinct, definable steps. [33] Further, the human brain does not consider problems one step at a time; therefore, forcing such thinking does not aid decision making.[34]

The contrast between linear and non-linear thinking is important when discussing decision making. Linear thinking can also result in overlooking information and forming judgements, assuming that a problem has well-defined and confined limits.[35] Conversely, non-linear thinking acknowledges that actions may yield disproportionate consequences, impacting the initial issues or giving rise to new situations.[36] The interaction within the problem is fluid and evolving.[37] The brain resolves issues by continuously generating ideas and testing them. Generating these ideas heavily relies on intuition, regardless of a person's experience level. There is substantial evidence that a significant portion, if not most, of information processing in the brain occurs subconsciously, with our conscious awareness representing just a small fraction of the entire process. Conversely, a strong inclination toward rigid thinking can render individuals more vulnerable to cognitive bias, as it tends to foster a narrow, one-track mindset that may overlook alternative options, differing perspectives, and the broader context. Some military planners identify that design thinking is an essential component of military planning processes and is a practice inherent to all planners throughout history.[38] It centres on problem solving, following a non-linear trajectory, and not concluding solely upon developing a solution.[39] However, what occurs in practice is a default to linear thinking. Therefore, there needs to be a sense-making perspective, with opportunities to pose questions, consider multiple perspectives, and analyse systems for complex environments.[40]

The Cynefin Framework as a planning tool

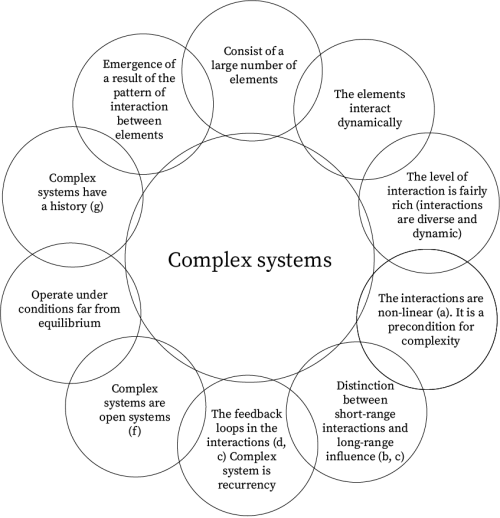

There may be no clear centre of gravity in complex environments such as warfare. Therefore, simple problems can be conjured out of very complex situations that result in diagnosing the wrong problem.[41] Yet this is one aspect of the problem. Thus, complex environments call for a different decision-making model. Cillier's 1998 model clarifies the characteristics of complex systems with 10 attributes, as seen in Figure 1 below. It helps planners understand and recognise uncertainty, comprehend the non-linear relationships in modern warfare and their interconnectedness, which allows planners to understand the ripple effects and unintended outcomes. This necessitates the creation of inventive and flexible decision models that go beyond the linear thought processes associated with conventional, rational, and strategic decision making.[42] The Cynefin model builds on this.

Figure 1: The characteristics of complex systems[43]

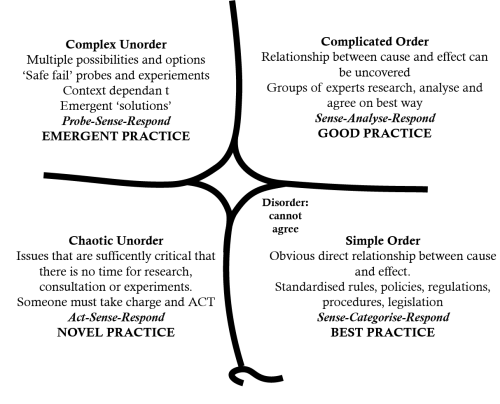

The Cynefin Framework was formulated in 1999 by D. Snowden during his work on knowledge management and business organisational strategies.[44] It is a model utilised in the civilian business world but transferable to the military context as it explores and supports complex decision making. It proposes four fundamental decision-making approaches, each contingent on the extent of contextual uncertainty, as depicted in Figure 2 below. Although doctrine manuals mention uncertainty, complexity, chaos, agility, and resilience, they offer no guidance in coping with them.[45] The Cynefin Framework promotes the utilisation of storytelling to comprehend the complexity and underscores the social elements of sense-making while considering diverse environmental factors. The difference between this and linear models is that it acknowledges complexity, it is adaptive in nature, it embraces uncertainty, and facilitates situational awareness. The most valuable part of this model is the focus on the complex quadrant where one probes, senses, and then responds, demonstrating the relationship between cause and effect in retrospect.[46] The chaotic quadrant is where one acts, senses, and responds and where there is no relationship between cause and effect at a systems level.[47]

Figure 2: Cynefin Framework [48]

This model can be used to best effect, to assess Australia’s strategic environment with its diverse geopolitical dynamics, ability to respond to change, the non-linear behaviours exhibited by regional players, interconnectedness, and patterns and requirements to develop planning that can withstand environmental shocks and disturbances. ‘It challenges basic assumptions such as the world is in order and known or knowable, people are always completely rational, and actions always point to underlying intent and never reflect happenstance.’[49] It demonstrates a different way of making decisions and identifying causal dynamics.[50] The Cynefin practices do not encourage groupthink.[51] They encourage collaboration, experimentation and exploration of multiple perspectives, which is contrary to groupthink. In contrast, there may be competing views with no clear answer as the complex environment represents situations where causality is not evident and outcomes are unpredictable.[52] It does not lead to clear guidance on what action to take and therefore lead to frustration when leaders require actionable plans. This may result in resistance to change when traditional JMAP methodologies are deeply ingrained. The Cynefin Framework offers value in obliquity, which is indirectly achieving objectives, and its inherent uncertainty in complex problem solving.[53] While JMAP simplifies issues into rational actions, it fails to account for unpredictable outcomes.[54] Design, planning, and execution are interconnected processes that adhere to best practices for addressing intricate problems and decision making.[55] However, it is important to note that this approach primarily pertains to the tactical and operational levels necessitating a more thorough evaluation of its suitability in military contexts.

Traditional military planning aims to reduce risk and uncertainty through a systemic approach, based on the idea that organisations can logically find solutions by collecting and analysing abundant data.[56] General James Mattis (rtd) emphasises, ‘Today's conflicts demand military who perform in an uncertain, ambiguous, complex, chaotic and inherently unpredictable environment.’[57] It is important to account for chance and friction in combat operations.[58] Therefore, military training and educational systems must equip personnel to anticipate conditions that may not currently exist, including dealing with unfamiliar cultures and adversaries who don’t adhere to Western values and principles of warfare.[59] To achieve this, it is essential to encourage lateral and creative thinking during information gathering and analysis to minimise bias. To effectively implement this approach, building expertise and providing military planners with adequate training is of utmost importance.

Applicability to military education and training

The ADF is not culturally ready to replace JMAP completely; therefore, any proposed changes must be incremental. The primary states of the JMAP are where analysis of data is key.[60] Implementing the Cynefin Framework in the JMAP scoping and analysis phase will enable further amendments to ensure deviation from the linear step model currently in practice.[61] It will help personnel understand the situation's nature better and help them make informed decisions and develop courses of action based on the characteristics of the problem faced. It is recommended that design thinking, including the encouragement of divergence, is included in the process. Additionally, placing the JMAP linear model within a non-linear appreciation of this operational environment through the Cynefin Framework across the spectrum of conflict will assist in balancing its negatives and positives. This transformation will also need to be trialled. This is because ‘transforming an organisation requires experimentation as well as failure’.[62]

The three stakeholders of JMAP are the main ADF organisation responsible for conducting joint operations planning, and those responsible for teaching joint operations planning as part of the ADF's Professional Military Education continuum.[63] There are differences between training and education, with training focusing on procedural applicability, and education on developing knowledge. Education also has the potential to mould culture, influencing how effectively military professionals adopt thinking behaviours aligned with a pluralist mindset, characterised by open-mindedness, adaptability, and readiness to evaluate perspectives. [64] However, the military's decision-making and planning processes are hindered by the limited thinking traits instilled in pre-war education.[65] The ADF will be called upon to produce leaders who can deal with unprecedented complexity and ambiguity.[66]What constitutes a beneficial pre-war education and the specific educational style that fosters a pluralist mindset before wartime remain unclear and undefined.[67] Further, Australia's military education is episodic at the rank levels, with junior officers focusing on tactical planning, middle ranks focusing on operational planning, and senior officers focusing on strategic planning, often contributing to narrow-minded thinking at varying ranks or levels.[68] This may not continue to suit the current environment of risk and uncertainty.

Educating inexperienced planners to strive for linearity is providing them with poor instruction as it is not teaching them to think. The non-linear process is most beneficial in the scoping and analysis and course of action phases of JMAP. While a linear process is not recommended in military planning, there is a place for a step process when teaching beginners. There still may be a requirement for checklists, procedures, or aide memoirs as 'training wheels' for these beginners. This is because the focus is on teaching the way of thinking rather than theory, process, or outcomes.[69] Further mastery will be obtained through mentoring, coaching, and experiential learning, learning through exercises and interactive class activities.[70] Exercises and scenarios must reflect integrated campaigns in multiple domains and not purely focus on high-end military conflicts. Training should encompass activities that encourage innovative thinking, relationship- building, and sense making. Using case studies and planning exercises supports this process and sharpens cognitive abilities to make sense of intricate or chaotic decision environments.[71] This is because adhering to rigid, linear, rational actor-style decision rules in highly uncertain conditions will likely yield suboptimal learning outcomes. Since no two situations are identical, ongoing exposure to new actual or simulated situations refines crucial skills.[72] Fostering non-linear reasoning and thinking involves recognising and perceiving emerging patterns, responding to them, and swiftly assessing and adjusting as necessary, utilising case studies and simulation exercises that may not appear military. Additionally, this should encompass identifying the contextual demands placed on various foreign leaders, government agencies, representatives of non-government organisations, civil leaders, and rebel force commanders within select case studies that expose uncertainty. [73] Consider, for instance, Ben Zweibelson's assertion that ‘sometimes, designers need to “Trojan Horse” some experimentation in organisations that are not quite ready or willing to increase uncertainty and risk’.[74] Overall, Military Planning training is more than meeting the learning objectives; it is about thinking and making meaning of the complexity of peace and conflict operations.

Conclusion

While Australia's strategic environment is a complex and uncertain one, the disconnect exists with the JMAP process, which is linear. The ADF needs to adopt a non-linear planning model. It is recommended that a broad JMAP process is applied with some edits in order to better apply the Cynefin Framework and design-thinking principles. The JMAP can be improved by introducing a non-linear framework. The Cillier’s model firstly provides insight into the intricacies and uncertainties of a complex environment. The Cynefin Framework applies insights from this to identify appropriate strategies and decision-making approaches for handling complex military scenarios. It can be used as a tool that is valuable for identifying issues and guiding decision making and actions within complex processes. It differentiates between the scenario's simple, complicated, and complex facets. It demonstrates sense-making activities to examine various data viewpoints and comprehensively understand that information.[75] Yet it would require testing and evaluation to ensure a smooth transition into military education and training. While linear planning is not an efficient methodology for teaching beginners, some may require a step process as they develop their proficiency with supporting tools. More importantly, military training needs to ensure that it exposes personnel to the complex and uncertain environments to prepare them for planning operations. Further, exercises and scenarios must be built into education and training to build expertise and develop skills. However, it is one thing to identify issues with a process but another to implement change. The ADF must continue to reflect critically on the JMAP process and not ignore lessons learned from previous conflicts and the military planning involved. The challenge is establishing an improved process before Australia heads into war, where the risk of failure is heightened.

Australian Government, Defence Strategic Review 2023, website, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 | About | Defence.

Banach, Colonel Stefan J, US Army and Ryan, Alex, The Art of Design: a Design Methodology. Military Review, March-April 2009: 105-115.

Berger, Jennifer Garvey & Johnston, Keith, Simple Habits for Complex Times: Powerful Practices for Leaders, Stanford Business Books, Stanford University Press, 2015.

Bosio, Nicholas John, ‘An analysis of the relationship between contemporary western military thought, systems thinking and their key schools of thought,’ Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, School of International, Political and Strategic Studies, College of Asia and the Pacific. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of ANU Canberra. February 2022.

Brougham, Greg, The Cynefin Mini Book, An introduction to complexity and the Cynefin Framework, Enterprise Software Development Series. The Cynefin Mini-Book - Greg Brougham - Google Books.

Cilliers, P. Complexity and Postmodernism: Understanding, New York, NY: Routledge: 1998.

Clausewitz Carl von, On War, ed. and trans. Howard, M & Paret, P, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976.

Department of Defence, 2016 Defence White Paper, Australian Government, 2016.

Dettmer HW, Systems Thinking and the Cynefin Framework. A Strategic Approach to Managing Complex Systems, Goal Systems International, 2011, Available at http://www.goalsys.com/books/documents/Systems-Thinking-and-the-Cynefin-framework-Final.3.pdf

de Terre, Armée, Jun 2010. FT-02 (ENG) General Tactics. Paris: Centre de Doctrine D’Emploi Des Forces, pp 39-41.

Dibb, Paul & Brabin-Smith, Richard, Deterrence through Denial: a strategy for an era of reduced warning time, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, May 2021: 4-31

Dobson-Keefe, Nigel & Coacker, MAJ Warren, Thinking more rationally: cognitive biases and the Joint Military Appreciation Process,Defence Science and Technology Organisation, Australian Army, Australian Defence Journal, 2015. pp 5-16

Echevarria, Antulio J, II, Rapid Decision Operations: An Assumptions Based Critique, Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 2002

Evans, Michael, The Closing of the Australian Military Mind: The ADF and Operational Art, Security Challenges, 14, 2, 105-131

Franke, Dr Volker, Decision Making under uncertainty: using case studies for teaching strategy in complex environments, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 13, 2, Winter 2011:1-21.

Gorzeni-Mitka, Ivona & Okreglicka, Malgorzata, Improving Decision Making in Complexity Environment, Procedia Economics and Finance, 16, 2014: 402-409.

Grant, Tim, Outlining Future C2 Doctrine using the Cynefin Framework, International Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, Quebec, Canada, October 2021, Conference Paper. Microsoft Word - ICCRTS 2021 Grant Outlining future C2 doctrine Ppr54 211111 post-print.docx (researchgate.net)

Gray, Colin, Strategy and Defence Planning – meeting the challenge of uncertainty, 2014, Oxford New York: 176

Hall, AD, A Methodology for Systems Engineering, Van Nostrand, 1962.

Hart Basil H Liddell, Strategy, 2nd Revised (1st Meridian) ed, London, UK: Meridian, 1967.

Jackson, Dr Aaron, A Tale of Two Designs: Developing the Australian Defence Force's Latest Iteration of its Joint Operations Planning Doctrine. Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 17, 4, Centre of Military and Strategic Studies, 2017: 174-193.

Jackson, A, 2013. The Roots of Military Doctrine: Change and Continuity in Understanding the Practice of Warfare. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press.

Jaclonsky, David, The Owl of Minerva Flies at Twilight: Doctrinal Change and Continuity and the Revolution in Military Affairs, Carlisle, PA; Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 1994.

Joint Publication 5-0 US Military.

Jomini, Antoine Henri, Précis de l’Art de la Guerre, 136-50 (Orders of Battle Overcome Uncertainty).

Kurtz CF, Snowden DJ, The New Dynamics of Strategy: Sense-making in a Complex and Complicated World, IBM Systems Journal 2003, 42, 3.

Macgregor, Douglas A, Future Battle: The Merging Levels of War, Parameters, 22, 4. Winter 1992-1993.

Merriam Webster Dictionary, Website Accessed 01 Sep 23, 130 Synonyms & Antonyms of PLAN | Merriam-Webster Thesaurus

Monk, Colonel Jeremy, USAF, The Fallacy of Modern Military Planning,, Air War College, USAF, 06 Apr 2017.

Nickols, F, Strategic Decision Making: Commitment to Strategic Action. Retrieved 20 Mar 2005, from http://www.nickols.us/strategic_decision_making.pdf

O'Neill, FLTLT Naomi, Teaching Junior Leaders to Think, Australian Army Research Centre, 28 Aug 2016.Teaching junior leaders to think | Australian Army Research Centre (AARC)

Palazzo, Albert, The Future of War Debate in Australia: Why has There Not Been One? Has the Need for One Now Arrived?, Working Paper 189, Land Warfare Studies Centre: Canberra, August 2012.

Paparone, C & Davis Jr, W, Exploring Outside the Tropics of Clausewitz: Our Slavish Anchoring to an Archaic Metaphor, 2012. Full article: The centre of gravity concept: contemporary theories, comparison, and implications (tandfonline.com)

Perez C. ed, Addressing the Fog of COG, Perspectives on the Center of Gravity in US Military Doctrine. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, Fort Leavenworth.

Ritzer, G, Sociology: A Multiple Paradigm Science. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1975.

Ryan, A, King, R, Bruscino, T & Cox, D, Full spectrum fallacies and hybrid hallucinations: how basic errors in thinking muddle military concepts. The Land Warfare Conference, Brisbane, Nov 2010.

Robert Scales, Return of the Jedi, Armed Forces Journal, October 2009 View of Decision-Making under Uncertainty: Using Case Studies for Teaching Strategy in Complex Environments (jmss.org)

Snowden D, Boone ME, Leader's Framework for Decision Making, Harvard Business Review, November 2007:69-76.

Strange, J & Iron, R, Center of Gravity: What Clausewitz Really Meant. Joint Forces Quarterly, 35,1, 2004: 20–27.

Tzu Sun, The Art ofWar, trans. Griffith, Samuel B, London, England, UK: Oxford University Press, 1963.

VanderSteen, K, 2012. Center of gravity: a quest for certainty or tilting at windmills,

Walker, David (Captain), Refining the military appreciation process for adaptive campaigning (informit.org), Australian Army Journal, 8, 2.

Zweibelson Ben, One piece at a time: why linear planning and institutionalisms promote military campaign failures, Defence studies, 15, 4, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group 2015:360-375.

Zweibelson Ben, Bleeding Postmodernism with Military Design Methodologies: Heresy, Subversion and other Myths of Organisational Change, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 17, 4, Jan 2017: 139-164.

1 Australian Government, Defence Strategic Review 2023, website, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 | About | Defence, p23.

2 Defence Strategic Review, op cit, p23.

3 Defence Strategic Review, op cit, p24.

4 Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976):101.

5 Merriam Webster Dictionary, Website Accessed 01 Sep 23, 130 Synonyms & Antonyms of PLAN | Merriam-Webster Thesaurus

6 David Walker, (Captain), Refining the military appreciation process for adaptive campaigning (informit.org), Australian Army Journal, 8,2, 2011:86.

7 Joint Publication 5-0 US military.

8 This quote is attributed to Albert Einstein.

9 Ben Zweibelson, One piece at a time: why linear planning and institutionalisms promote military campaign failures, Defence studies, 15, 4, (Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2015): 360.

10 Colonel Jeremy Monk, USAF, The fallacy of modern military planning, Joint Publication 5-0 US Military, 06 Apr 2017, 4.

11 Colonel Jeremy Monk, op cit, p5

12 P. Cilliers, Complexity and Postmodernism: Understanding, New York, NY: Routledge: 1998.

13 As an illustration, the top three influential theorists (Clausewitz, Sun Tzu and Liddell Hart), all reference uncertainty, confusion, and disproportionate outcomes in war. The fifth most influential (Jomini) also discusses uncertainty. However, Jomini says this can be managed through his articles of warfare. See: von Clausewitz, On War, 75, 84-88 (Uncertainty and Friction), 148-49 (war as art or science); Sun Tzu, The Art of War, trans. Samuel B. Griffith (London, England, UK: Oxford University Press, 1963), 91-93 (V:4-20); Basil H. Liddell Hart, Strategy, 2nd Revised (1st Meridian) ed. (London, UK: Meridian, 1967; repr., Meridian 1991), 5-6 (Indirect and Disproportionate Responses), 323-24 (Incalculable Elements); Jomini, Précis de l'Art de la Guerre, 136-50 (Orders of Battle Overcome Uncertainty); Nicholas John Bosio, "An analysis of the relationship between contemporary western military thought, systems thinking and their key schools of thought," Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, School of International, Political and Strategic Studies, College of Asia and the Pacific, A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of ANU Canberra. February 2022.

14 Jennifer Garvey Berger, Keith Johnston, Simple Habits for Complex Times: Powerful Practices for Leaders, Stanford Business Books, Stanford University Press, 2015, 8.

15Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith, Deterrence through Denial: a strategy for an era of reduced warning time, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, May 2021: 9.

16 Department of Defence, 2016 Defence White Paper, Australian Government, 2016:34, 40.

17 Paul Dibb, Richard Brabin-Smith, op cit, p5.

18 This means strategic, operational and tactical levels of war. Critics include:- David Jaclonsky, the owl of Minerva flies at twilight: doctrinal change and continuity and the revolution in military affairs, (Carlisle, PA; Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 1994); Douglas A. Macgregor, Future Battle: the Merging Levels of war, Parameters, 22, 4. Winter 1992-1993); Antulio J Echevarria, II, Rapid Decision Operations: An Assumptions Based Critique (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 2002).

19 David Walker, ibid, 87.

20 Tim Grant, Outlining Future C2 Doctrine using the Cynefin Framework, International Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, Quebec Canada, October 2021, Conference Paper, 13. Microsoft Word - ICCRTS 2021 Grant Outlining future C2 doctrine Ppr54 211111 post-print.docx (researchgate.net).

21 Tim Grant, op cit, p13.

22 G Ritzer, Sociology: a multiple paradigm science. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1975, 7.; Jackson, A., 2013. Ritzer 1975, p. 7; Jackson 2013, p. 3.

23 Ben Zweibelson, ibid, 372.

24 “The ADF tends to prioritise individuals who take action over those that engage in deep thinking”. Albert Palazzo, “The Future of War Debate in Australia: Why has There Not Been One? Has the Need for One Now Arrived?”, Working Paper 189, Land Warfare Studies Centre: Canberra, August 2012.

25 A. Ryan, R. King, T Bruscino, and D.Cox, Full spectrum fallacies and hybrid hallucinations: how basic errors in thinking muddle military concepts. The Land Warfare Conference, Brisbane. Nov 2010, 247

26 Armée de Terre, Jun 2010. FT-02 (ENG) general tactics. Paris: Centre de Doctrine D’Emploi Des Forces,39-41.

27 J. Strange, R Iron, Center of gravity: what Clausewitz really meant, Joint Forces Quarterly, 35, 1, 2004:20–27; C.Paparone, W. Jr Davis, Exploring outside the tropics of Clausewitz: our slavish anchoring to an archaic metaphor,2012. In: C. Perez, ed., Addressing the fog of COG, perspectives on the center of gravity in US military doctrine, Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, Fort Leavenworth,66; K.VanderSteen, Center of gravity: a quest for certainty or tilting at windmills, 2012. In: C. Perez ed., Addressing the fog of COG, perspectives on the center of gravity in US military doctrine, Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, Fort Leavenworth, 39.

28 David Walker, ibid, 85.

29 David Walker, ibid,86.

30 Colonel Jeremy Monk, ibid, piv.

31 Colin Gray, ibid, 176.

32 Colin Gray,ibid, 176.

33 David Walker, ibid, 88.

34 David Walker, ibid, 88.

35 Gerd Gigerenzer, Peter M. Todd, and A. B. C. Research Group (Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999), 14-15; Rosenberg, The Not So Common Sense,3-8; Gigerenzer and Goldstein, "Betting on One Good Reason," 75-77; David Paul Todd, "A 'Dynamic' Balanced Scor ecard - The Design and Implementation of a Performance Measurement System in Local Government" (Master of Commerce in Management Science and Information Systems University of Auckland, 2000), 41.; Rosenberg, The Not So Common Sense, 81.

36 Nicholas John Bosio, An analysis of the relationship between contemporary western military thought, systems thinking and their key schools of thought, Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, School of International, political and strategic studies, College of Asia and the Pacific, A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of ANU Canberra. February 2022,75.

37 Nicholas John Bosio, op cit, 75.

38 David Walker, ibid, 98.

39 Colonel Stefan J Banach, US Army, and Ryan Alex, The art of design: a design methodology. Military Review, March-April 2009: 105.

40 Jennifer Garvey Berger, Keith Johnston, Simple Habits for Complex Times: Powerful practices for Leaders, Stanford Business Books: Stanford University Press, 2015, 16.

41 David Walker, ibid, 94.

42 Ivona Gorzeni-Mitka and Malgorzata Okreglicka/Procedia, Economics and Finance 16 (2014) 402-409,4.

43 Cilliers, P. (1998). Complexity and Postmodernism: Understanding. New York, NY: Routledge, 3-4; Ivona Gorzeni-Mitka and Malgorzata Okreglicka, Improving Decision Making in Complex Environments, Procedia Economics and Finance 16, 2014.

44 Ivona Gorzeni-Mitka, Malgorzata Okreiglicka, ibid, 405.

45 Tim Grant, ibid, 1.

46 Ivona Gorzeni-Mitka, Malgorzata Okreiglicka, ibid, 406.

47 Ivona Gorzeni-Mitka, Malgorzata Okreiglicka, ibid, 406.

48 D.Snowden, M. E. Boone, A Leader's Framework for Decision Making, Harvard Business Review, November 2007, 69-76; C. F Kurtz, D. J. Snowden The new dynamics of Strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world, IBM Systems Journal 2003, 42; H. W. Dettmer, Systems Thinking and the Cynefin Framework. A Strategic Approach to Managing Complex Systems, Goal Systems International, 2011, Available at http://www.goalsys.com/books/documents/Systems-Thinking-and-the-Cynefin-framework-Final.3.pdf

49 F. Nichols, Strategic decision making: Commitment to strategic action, retrieved March 20, 2005, from http://www.nickols.us/strategic_decision_making.pdf

50 Ivona Gorzeni-Mitka, Malgorzata Okreiglicka, ibid, 406.

51 Greg Brougham, The Cynefin mini book an introduction to complexity and the Cynefin Framework, Enterprise Software Development Series,10. The Cynefin Mini-Book - Greg Brougham - Google Books.

52 Greg Brougham, op cit, 11.

53 Greg Brougham, op cit, 11.

54 Greg Brougham, op cit, 12.

55 This basic model is taken from A.D. Hall, A Methodology for Systems Engineering, Van Nostrand, 1962. The ‘systems approach’ encompasses a large variety of models and methods. This is considered to be the most foundational and thereby capable of accommodating other models and techniques that one might choose to apply from time to time.

56 Robert Scales, ibid, 6.

57 This quote is believed to have been stated when Mattis was a Major General commanding the 1st Marine Division during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, cited in Nicholas Bosio ibid, 127.

58 Colonel Stefan J Banach, ibid, 106.

59 Robert Scales, Return of the Jedi,‛ Armed Forces Journal, October 2009, 22.

60 Nigel,Dobson-Keefe, MAJ Warren Coacker, Thinking more rationally: cognitive biases and the Joint Military Appreciation process,Defence Science and Technology Organisation, Australian Army, Australian Defence Journal, 2015, 9.

61 This was covered in ACSC lectures from 13 Jun 23 on Epistemic ideologies.

62 Ben Zweilbelson, 2017, 143.

63 Dr Aaron Jackson, A Tale of Two Designs: Developing the Australian Defence Force’s Latest Iteration of its Joint Operations Planning Doctrine, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 17, 4, Centre of Military and Strategic Studies, 2017, 180.

64 Nicholas John Bosio, ibid, 267.

65 Nicholas John Bosio, ibid, 267.

66 Michael Evans, the closing of the Australian Military Mind: the ADF and Operational art, Security challenges, 14, 2, 131.

67 Nicholas John Bosio, ibid, 288.

68 Nicholas John Bosio, ibid, 289.

69 FLTLT Naomi O’Neill,Australian Army Research Centre, Teaching Junior Leaders to think 28 Aug 2016.Teaching junior leaders to think | Australian Army Research Centre (AARC).

70 Colonel Stefan J Banach, ibid, 106.

71 Robert Scales, ibid, 17; Dr Volker Franke, Decision Making under uncertainty: using case studies for teaching strategy in complex environments, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Vol 13, Issue 2, Winter 2011, p1-21.

72 Robert Scales, ibid, 19.

73 Robert Scales, ibid, 21.

74 Dr Aaron Jackson, ibid, 185.

75 Ivona Gorzeni, ibid, 408.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.