What is the Most Significant Ethical Challenge for the Application of Military Power in the Twenty First Century?

A Compilation

Compiled by Lieutenant Colonel Rob Alsworth

The Australian Command and Staff Course completed a six day ethics package between 7th – 15th March 2019 at Weston Creek, ACT. The package was structured into four sections, three of which were two day sub-packages entitled Foundations, Application and Future. The fourth section, Confirmation, was not bound by time but rather ran as a theme throughout the package. Confirmation centred on a question set at the beginning of the package, to be considered throughout the other three sections and answered at the end. The question is at the top of this paper and each of the fourteen syndicates, of twelve to thirteen members, was tasked to prepare a 500 word paper as their answer.

The purpose of this task was to encourage students to consider ethical themes throughout the package, engage in focussed debate with their syndicate group and synthesise their discussions into a concise, peer reviewed argument. The exploration of ethical theories and case studies can be highly emotive and personal. It is challenging to take the disparate and passionately held views of twelve or thirteen syndicate members, analyse their constituent parts and fuse them together into a coherent, written argument. The students and staff engaged with the task enthusiastically and produced some very good responses.

Compiled for your reading are eight of the fourteen responses. Their conclusions are varied but with common themes. Several papers argue that the recent character of war against non-state actors is an ethical challenge. Some argue the breadth of significant technological advancements have created an environment where war is more remote from the societies that wage it and thus creates new ethical challenges in civilian/military relationships. Another paper has focused on cyber as the single technological leap that causes the most significant ethical challenge for the twenty first century. The final paper questions the validity of a fixed ethical framework in an ever evolving operational context.

Please read and pause for a moment to consider the points raised. None of these papers have the answer because in ethics and warfare there cannot be a single answer. The Australian Command and Staff Course challenges readers to consider the question set and submit their own paper, not more than 500 words, to answer:

What is the most significant ethical challenge for the application of military power in the twenty first century?

Syndicate Two: What is the most significant ethical challenge for the application of military power in the twenty first century?

The most significant ethical challenge identified was the prosecution of armed action against non-state armed belligerents identified as enemies of the state, in particular the targeting of these elements within the borders of countries not committed to the hostilities. Examples include U.S. drone strikes against Taliban forces in Pakistan, Colombian raids into Ecuador to target FARC terrorists, or Turkish attacks on Kurdish fighters in Iraq and Syria. None of these countries were formally declared as belligerents in the conflict that saw military action conducted within their borders.

The first concern is the use of lethal force without attempt at negotiated resolution. If war must ethically be considered as the last resort, then prosecution of extra-theatre lethal targeting should be viewed in the same manner. An example is the use of Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) to target Taliban and associated militants in Pakistan during the war in Afghanistan. Without recourse to dialogue and negotiation, continued strikes lose their ‘coercive’ ability to threaten or gain leverage for settlement, becoming a purely punitive instrument. This raises the further ethical consideration that continued killing of personnel extra-theatre may not be justifiable, as it does not contribute to the conclusion of hostilities.

The second concern is that the lethal targeting of personnel outside recognised combat zones increases the potential for accusations of unlawful killing, particularly if collateral damage results in non-combatant deaths. In turn, this may provide perceived legitimacy to retaliatory terrorist actions within other countries as a justified response. Colombia provides an example, where security forces killed FARC terrorists during a raid without notice into Ecuador in 2008. Although achieving the objective, it heightened regional tensions, with Ecuador recalling its ambassador and Venezuela mobilising troops. Similar actions may contravene the ethical responsibility to limit conflict, and to reduce avoidable loss of life.

A final concern is the conduct of allies, and potential differences in ethical viewpoint and practices. This is evident in Iraq and Syria, where the Coalition supports multiple armed groups fighting ISIS. Conduct of some groups has been questioned, and the ethical responsibility for their actions could be attributed to those that armed them. In addition, it may be unethical to support one armed group against another if they are both engaged in what may be considered terrorist activity. An example is Coalition support for Kurdish forces in Iraq (PKK) and Syria (YPG), whom Turkey considers terrorist organisations and actively targets. The ethical dilemma is then the knowledge that arms and funds provided may be diverted to other undesired causes, arming them for continued conflict elsewhere.

A potential means of reducing these ethical concerns is through early negotiation. Negotiation (not appeasement) may actually force groups into self-regulation, allowing them to react to concessions by moderating behaviour and transitioning to dialogue. Addressing grievances builds international credibility, and erodes moderate support for extremist views and actions. Armed force may still be necessary and justified as an initial response, but negotiation must be an agreed course of action to reduce the likelihood of a cycle of perpetrated violence.

Syndicate 3: What is the most significant ethical challenge for the application of military power in the twenty first century?

The most significant ethical challenge in the application of military power in the twenty-first century is the convergence of technology with rising incremental moral compromise, which may ultimately corrode the state’s decision-making ability in the application of military power.

Technological advances, such as artificial intelligence, automated processing and weapon development introduce three distinct issues which produce ethical conundrums to the state’s application of military power. First, technological advancement may create weapons which are more lethal and precise. Increased lethality necessitates clear understanding of the State’s end state which can be influenced by international security and alliances, state resources or an actor manipulating population perspectives. Consequently, the state’s ability to apply just and proportionate military power can be ethically compromised through competing perspectives. Second, artificial intelligence and weapon automation may reduce human involvement in executing military power, incrementally corroding morals by dehumanising violence whilst increasing the risk of further conflict due to lack or lapses in human control. Finally, technological advancement increases access to data and information which can confuse an operators environmental understanding. Therefore, the ethical challenge associated with technological advances is not in and of itself the possession of a capability. Rather, the challenge is the state’s ability to make ethical decisions in the application of those technologies in an international system and an environment where decision making is vulnerable to manipulation and misinterpretation.

The increasing complexity of the information domain will also challenge the state’s decision-making and how its actions are perceived by the population. The 24-hour news cycle, near-universal social media access, and complex political, and societal factors introduce unprecedented levels of information for consideration. Not only can the information be easily manipulated or exploited, but the state’s inability to dominate the narrative can rapidly erode population support in the application of military power. Further, the scrutiny applied to decisions, particularly when employing military power to the use of non-conventional weaponry or complex humanitarian intervention – both of which have important moral and ethical implications, can significantly affect a state’s decision-making ability.

Finally, a military force’s ability to represent its national ethics, beliefs and values – despite the requirement to stand by allies – is a considerable challenge to ethically applying military power. The contemporary globalised environment requires military forces to work alongside foreign nations whose beliefs and values may be contrary to its own. Alliances can draw partners into conflicts which may contravene one’s view of what constitutes a just war, compounding this challenge. A further complication occurs when politicians and military leaders lack the moral courage to represent national interests and military capabilities appropriately. A challenge for leaders will be to have the moral courage to accept and communicate the risks to their forces in response to a State’s planning, regardless of the second-order implications. Thus, it is the combination of technology, a complex human domain, and a potentially degraded ethical framework which complicate states’ decision-making and represents the most significant ethical challenge in the application of military power in the twenty-first century.

Syndicate 5: What is the most significant ethical challenge for the application of military power in the contemporary world?

Australia and its allies are currently engaged in operations wherein military force is being applied across the broad spectrum of conflict. This includes involvement in Great Power competition, as characterised by a technologically charged arms race, to engaging in limited conflict with non-state actors such as Islamic State. This paradigm presents the most significant ethical challenge to the application of military power in the contemporary world, because it will increasingly risk the prospect of ethical compromise. The first risk of ethical compromise is our (and our allies) response to China’s proliferation of Artificial Intelligence, Cyber and Autonomous Weapon System capabilities; employed unethically or in a manner that increasingly removes the human involvement in the ‘kill chain’. The second risk of ethical compromise is our response to morally abhorrent non-state actors who increasingly seek war amongst the people, including within our own sovereign borders.

China is determined to lead and proliferate military Artificial Intelligence, Cyber, and Autonomous Weapon Systems. In turn, to remain competitive, Australia and its allies must respond in an escalating manner to avoid military or technological inferiority. It is unknown if China, or other state actors, will have humans interacting as part of this technology; either ‘in the loop,’ ‘on the loop,’ or completely ‘out of the loop.’ Human interaction with technology poses different challenges for the human operating the system; cognitively, emotionally and ethically. The potential for ethical challenges exist; these and the true second and third order effects are unable to be quantified due to the emergent operating environment. Allowing AI to autonomously take control of a military situation is a sub-optimal outcome. There must be a human either ‘in the loop’ or ‘on the loop’ of these powerful and destructive systems. One of the benefits that we enjoy today is that military personnel are more educated, inquisitive and comfortable with technology and confident to question a supervisor’s directions and/or actions. This provides an ongoing human ‘in the loop.’ Our adversaries may not be this way inclined, providing them with military superiority and leaving us with only ethical superiority. We must not compromise this ethical superiority when confronted with the possible need to respond to China’s determination to lead and proliferate military Artificial Intelligence, Cyber, and Autonomous Weapon Systems.

Confronting non-state actors such as Islamic State presents the ethical challenge of maintaining jus in bello as conflict trends increasingly toward ‘war amongst the people.’ The availability of real-time, high definition media will impact on the interplay of Clausewitzian tenets ‘passion, reason, chance’ by delivering the graphic and emotive savagery of war to the home front. The moral impact of unethical military means, by western standards, such as child suicide bombers, beheadings, destruction of cultural artefacts and chemical attacks will increasingly challenge the military’s ethical foundations. Similarly, the impact on a nation’s will to fight will be affected. How a government ethically rationalises and articulates the decision to intervene or otherwise in these ‘wars of choice’ to the domestic population, will be a significant challenge.

Taking an a-contextual view: ethics provide a critical foundation that binds the elements of Clausewitz’s trinity ensuring that war efforts remain acceptable to all parties. In that sense, the fundamental challenge of ethics in conflicts has not changed. Contemporarily, what is increasingly required in the future is to transpose and resolve perennial ethical challenges to changes in technology (means) and new conflict types (ways).

Syndicate 6: What is the most significant ethical challenge in the application of military power in the 21st Century?

This submission was developed in collaboration with non-western contributors but is primarily focussed on ethical challenges for Western militaries.

The most significant ethical challenge in the application of military power in the 21st Century is the technological, cultural and practical detachment from the reality of war and its inherent human suffering. This detachment will, if left unchecked, lower the threshold for the use of lethal force.

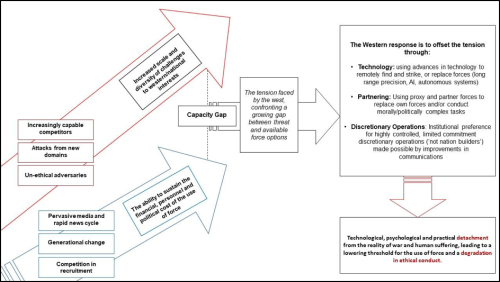

Figure 1. Offset and Detachment in the West

A number of developments in contemporary military practice serve to separate armed forces from the human results of military action. Forces have an enhanced ability to exercise military force at a distance, through long range and airborne precision strike, the use of autonomous and remotely piloted systems, supported by advances in pervasive sensor capabilities. Progress to make these technologies even more capable - including the use of AI and machine learning - is inevitable. Western forces are also demonstrating an increasing preference for partner force operations. The use of proxy and partner forces allow the West to conserve their own forces, provides greater flexibility in complex political, cultural and ethical environments, and allows the West to keep those complexities at arm's length.

The development of partner force operations reflect a trend in contemporary conflict. Western countries have demonstrated an institutional preference for highly controlled, limited commitment discretionary operations. Strategic thinking in the West has been increasingly focussed on minimising commitment – in particular the commitment of people – in the interest of economy of effort and in an effort to avoid moral entanglement. The increased capacity of strategic real time communications has set the conditions for these operations, as senior military officers and political staff are afforded far greater discretionary control of military operations. The desire to pursue limited and discretionary operations, whose conduct and objectives are managed at extreme distance, exacerbate detachment from the human face of war.

These trends share a common aspect: the desire to use limited forces as efficiently and in as discretionary a way as possible; replacing them, augmenting them or using force in new ways. This trend is inevitable due to a latent tension in the West. On the one hand, adversaries are becoming more capable – including new threats, and threats that use non-traditional, asymmetric and even inhumane methods. On the other hand, the West is faced with an increasing human, financial and popular cost of military force – a combined effect of increased media scrutiny, financial pressure and challenges to recruitment. Put simply, military force is increasingly necessary, but is becoming more costly. All of the trends identified above – technology, partnering and discretionary operations - have come about as the West has sought ‘offsets’ to this tension.

The inevitable trend is for the West to seek offsets, and these offsets serve to make war less human. All of these offsets are designed to allow limited forces to achieve greater military impact, but the inevitable outcome of this is that forces, planners and politicians can become increasingly detached from the human consequences of military force. If not managed, this detachment will lower the threshold for the use of military force as personnel lack the psychological constraint generated by having to manage the human and practical consequence of military action. The most significant ethical challenge will be technological, cultural and practical detachment from the reality of war and its inherent human suffering that will, if left unchecked, lower the threshold for the use of lethal force.

Syndicate 9: What is the most significant ethical challenge in the application of military power in the 21st Century?

The execution of military power at ever increasing geographical, social and cultural distance creates the situation where a nation is largely blinkered to the moral and psychological gravitas of the actions committed in its name. This results in potentially lowering the threshold for armed conflict and furthering the civilian-military divide and is the most significant ethical challenge facing the application of military power today.

In the past, in the seas of Trafalgar, the trenches of Verdun and the sky thousands of feet over Nazi Germany, whole societies came to know the horror of what was being carried out in their names. Whilst media teams were not aside Nelson, shouldered with muddied privates or in every Lancaster as they fought and killed each other; those who did survive brought back stories, en masse thanks to conscription, and informed the national psyches of what war was. As horrifying as it was, these wars were for national survival, and it was accepted that they must be waged to ensure the very existence of the state.

Contrast the previous statement to now. No developed Western nation has fought a war of national survival since 1945. Instead, they have fought wars of choice; those of containment, remediation of dissident client states and more recently suppression of terrorism and the establishment of favourable geopolitical arrangements in crucial resource areas . At the same time, militaries have become smaller, more professional and more able to prosecute precise and terrible violence from great range. All of this leads to two outcomes. First, war is a tool that carries a diminishing risk for the side employing high technology and expeditionary tactics.

Secondly, war is prosecuted by an ever-shrinking force of professionals with which the people, and the government, have a dramatically declining chance of shared experience in the prosecution of their state’s military action. Both of these outcomes lead to a general disassociation with the human impacts of war.

In the scenario in which a nation’s population has the horrors of war removed from its psyche, there is the risk that it may be more be likely to rush to armed conflict as there is a reduced understanding of why war should be the last resort . Developed nations will once again likely fight wars of national survival that will re-acquaint their people and the state with it’s true horror and consequence. But until that time, how many smaller wars of choice will kill and disfigure combatants and non-combatant alike because war was entered into so readily by peoples, governments and militaries for whom the prosecution of a war has become a matter of such little national significance?

Syndicate 10: What is the most significant ethical challenge in the application of military power in the 21st Century?

We consider that the great challenge for democratic governments and military forces this century will be to continue to ensure that the ethical and moral perspectives of the nation remain aligned with and supportive of the use of military power, particularly in an environment where military technology is evolving towards the use of autonomous weaponry, Artificial Intelligence, cyber warfare and advanced biological military applications.

Military technologies that remove (or appears to remove) human control over the decision to employ lethal force, or that is designed to artificially enhance of alter a human being in such as way as to challenge concepts of humanity, are increasingly regarded with concern by democratic populaces, and it is critical that the military forces of such democracies retain public trust in order to be allowed the responsibility to use such technologies to legally and morally prosecute armed combat.

It is well understood within modern military communities that advances in military weapons systems and the increasing speed and lethality of stand-off weapon systems will require the development of advanced software to analyse data and deploy weaponry at speeds greater than human cognition can process. However, while the public may be able to be educated to understand this necessity, government and militaries need to be able to explain the requirement for such weapon systems through an ethical framework and demonstrate that the military is able to use such systems in an ethical and human-controlled manner.

This will require the clear articulation of the military contexts in which such weapons systems are used, why they need to be used and in what kind of operations, and how the use of such technology is being effectively risk-managed. Morally, governments and militaries will need to answer the perennial ethical question of whether the ends of a particular military operation justify the advanced technological means being proposed.

Furthermore, government and militaries will need to demonstrate awareness of risks, and the consequent application of adequate safeguards to avoid technological escalation, both during and between wars. In certain circumstances this may require a sub-optimal utilization of a capability to ensure that a “man in the loop” C2 mechanism is retained for deployment of ethically contentious technologies.

Where such human-decision making control of an advanced capability is simply not feasible, or where the long-term effects of an evolving technology are unclear, governments and militaries may expect public debate and potential loss of trust. In an information age, errors of unintended consequences in the deployment of such technologies will be swiftly made known to both domestic and international audiences, and this poses significant and strategic legitimacy issues for democratic military forces regarding the means by which they conduct warfare.

If this debate and distrust is not effectively managed by the governments and military force of democratic nations, it has the potential to undermine legitimate strategic and military objectives in war to such an extent that it compromises the effective prosecution of national strategy.

Thus we contend that the greatest military challenge of the 21st century for democratic nations is to maintain public trust in its governments and military forces to use autonomous, adaptive and human-enhancing military technology in a responsible and ethical way and so consistently adhere to just war principles along the full and evolving spectrum of warfare.

Syndicate 12: What is the most significant ethical challenge for the application of military power in the twenty-first century?

The defining feature of the twenty-first century is the advent of the Information Age. The implications of this technological shift are yet to be fully realised either at a political nor military level. The complex, ambiguous and evolutionary nature of cyber warfare presents as the greatest challenge to contemporary ethical understanding as it pertains to the application of military power. These pressures will be experienced across the full spectrum of government agencies including policy makers, intelligence analysts, and military practitioners. By operating in an undefined zone between war and peace, cyber warfare raises new dilemmas for judging the ethical and legal foundations for war (jus ad bellum) and the conduct of war itself (jus in bello).

In considering jus ad bellum, the information age challenges the existing concepts of sovereignty, as activities in the cyber domain can exist simultaneously cross multiple geographic locations, transit through multiple third party via the global communications network. The advent of cyber warfare, with varying degrees of attribution, present a challenge in understanding what represents a significant violation of sovereignty and whether this justifies military action. In democracies there may be a requirement to sift through competing narratives of varying trustworthiness: information will be questioned but may not be revealed to the wider public due to the classification of systems and the risk of embarking on misdirected military action or unintended consequences is real.

In the offensive front, new technologies present military options which appear attractive to politicians due to their ‘non-kinetic’ nature but with second order and cascading effects much more difficult to predict. Cyber-attacks offer the promise of being able to deliver damaging effects on an opposition without the need to deploy physical forces. However, unlike the generally predictable effects of conventional weapons, cyber-attacks can be much harder to contain and limit in temporal, special and geographic effect. Furthermore, whilst the authorities for deploying physical military force are generally well established, the criteria for approval of cyber activities has not been well defined and include civilian participants as much as military personnel. Thus, the information age presents significant challenges for leaders and policymakers in deciding whether the conduct of war is just, and the options in which it can be prosecuted.

Providing a separate but equal challenge is how these weapons are employed. The employment of information warfare provides an additional ethical dilemma by challenging the existing framework of jus ad bellum, with no current international conventions in place to regulate the operations of cyber warfare. Cyber technologies provide some incredible potential to enhance our capacity to fight wars but will challenge accepted norms for what constitutes ethical conduct. In particular, the advent of autonomous, augmented and artificial intelligence is widely accepted as being an area of concern.

As nations seek to capitalise on the benefits offered by cyber warfare, the implications to jus ad bellum and jus in bello will continue to develop. Indeed the inexorable benefits of cyber warfare are its most intractable challenges. The blurred lines of sovereignty, agency and attribution in cyber warfare, let alone the direct effects of the attack itself, present as the most significant ethical challenge in the application of military power in the twenty first century.

Syndicate 13: What is the most significant ethical challenge for the application of military power in the contemporary world?

The most significant ethical challenge for the application of military power in the contemporary world is achieving balance in the tensions between a continuously evolving context against the desire for a fixed ethical baseline. Military professionals often find themselves between deontological and utilitarian approaches to decision making; what am I bound to do by the rules, against what achieves the highest good. This challenge becomes greatest in areas where the recognised rules are yet to mature, typically in the use of rapidly evolving technologies and a changing operational and strategic environment.

Extensive experience on operations focused on the liberation of populations-in-being over the past two decades has seen the Australian Defence Force develop a robust ethical baseline on how to manage complex situations in the countries of others. This understanding is taught to our people from the lowest levels, and has its foundation in a range of coherent Service and Defence-wide values-based programs.

However, we are progressively facing a range of considerations to which we are not necessarily accustomed. A challenge to Western hegemony in the Indo Pacific, the threat of high-intensity war, and a variety of rapidly evolving technologies have placed us in a position where current norms may require re-evaluation in the context of a changing operational environment. Likewise, we are now faced with a need to consider national economic and diplomatic interests that have far more relevance to Australian prosperity than previously encountered. This is further complicated by significant shifts in the current rules-based global order that we have come to rely upon. In this complex and technologically evolving landscape, ethical considerations and boundaries become less clear: we need to formulate methods to translate our developed ethical experience into a workable ethical baseline more responsive to the evolving future environment.

Developing a responsive ethical baseline for the future environment

The path from contemporary ethics to those that will suit our future operating space will likely be beset with missteps and experience from which we'll need to develop a revised baseline. However, that does not mean that the standards we currently advocate are no longer applicable. Current measures such as Laws of Armed Conflict and the principles of Rules of Engagement will remain relevant. However, in applying these standards, we must now embrace the inherent differences between traditional human-centred physical military engagements, and evolving operations involving cyberspace, autonomous vehicles and artificial intelligence.

A critical element in this transition is continued focus not simply on outcomes (the ends), but upon the process (the ways) in which we employ new systems (means) to achieve the outcome. The need to apply proportionality, respect for non-combatants and to minimise undue suffering will persist. However we will need to establish - and also attempt to achieve global agreement upon - where those ethical boundaries will now lay for the employment of evolving high tech ways and means. In many cases we are not likely to identify an exceedance until one actually occurs, due to the unseen nature of new effects. Ultimately, the nature of how we undertake ethical considerations will likely remain relatively static, but how these apply to new environments must evolve if they are to stay relevant and effective.

The need to understand how we can continue to apply and adapt our current ethical norms and bias to a rapidly evolving operational environment is the most significant ethical challenge for the application of military power in the contemporary world. The answer requires a flexible approach that draws upon our current proven ethical foundation, but recognises when new technologies and a changing geopolitical environment necessitate new and novel application of this thinking. The need for reliable and predictable decision-making underpins this, but this need must adapt and evolve with the arising challenges encountered.

Social Mastery

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.