The Case for Secular Inclusion

In 2021, The Forge published an article that presented a case for uniformed secular wellbeing practitioners in the Australian Defence Force (ADF), and a move away from the exclusive model of religious (overwhelmingly Christian) chaplaincy. The article, Losing our Religion[1](Hoglin, 2021), prompted discussion and positive and negative responses from various secular and religious advocates.

A key component of the discussion was an acknowledgement that most of the Defence population was no longer affiliated with a religion and that this proportion would further increase in the years ahead. With the relatively rapid change in religious composition, it was suggested that pastoral care and wellbeing support services should reflect this changing reality. Non-religious practitioners such as counsellors, psychologists, social workers and others should be used by Defence, together with the traditional religious chaplain for those who remain aligned with a religion.

In this article, a different approach is taken by presenting two practical workforce planning reasons for why Defence needs to hasten its consideration of a uniformed secular wellbeing capability. First, data concerning the likely religious affiliation of the next generation of recruits is explored to highlight that the loss of religiosity will continue unavoidably and the current trend is not simply a temporal anomaly. Second, the sustainability of the ADF’s attempts to continue to attract and appoint religious chaplains in the numbers currently required by the Navy, Army and Air Force to fill their establishment will be questioned against the backdrop of national workforce supply and demand for ministers of religion. An increased demand for secular wellbeing practitioners from Defence members, combined with a reduced supply and availability of religious chaplains, should provide a prima facie catalyst for Defence to more seriously embrace uniformed secular options for a wellbeing and pastoral capability.

Still losing our religion

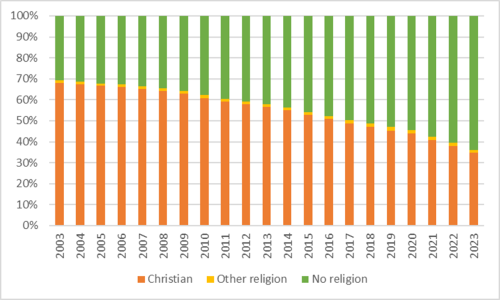

The trend toward reduced religious affiliation has not slowed since the publication of Losing our Religion. On 1 January 2023, almost 64 per cent[2] of permanent force members in the ADF did not identify with any religion. Having increased by an average of 3 per cent in each of the previous three calendar years, this change was higher than anticipated and continued the march toward a prediction that 75 per cent would not be affiliated with a religion by 2030. Data suggests that the faster pace of change is due to the separation of older (and more religious) members and the simultaneous recruiting of less religious members; a trend set to continue as Defence pushes to increase recruiting over the next few years.

The continued decline in religious affiliation should not surprise those who have observed the figures over time. Shown in Figure 1, there has been a gradual decrease from a workforce where 68 per cent were Christian and just 31 per cent non-religious in 2003 (1 per cent of other non-Christian religions), to one where these figures will likely be inverted within in the next 24 months (still with just 1 per cent of other religions). On current short-term trends, two-thirds of the ADF will have no religious affiliation by the end of 2023, less than one-third will remain affiliated with Christianity, and just 1 per cent will remain affiliated with a non-Christian religion.

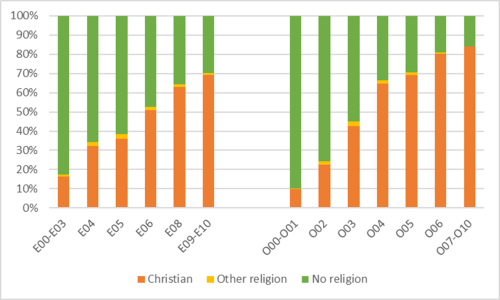

While it is relatively intuitive that recruiting has been the driving force behind the change (rather than members electing to change their affiliation after enlistment), the magnitude of the decline in religious affiliation among the ADF’s newest members might be unexpected and is worthy of closer exploration. Figure 2 shows that the most junior Defence members, typically the youngest and comprised of Privates (and equivalent in other Services) and Officer Cadets (and equivalent in other Services), overwhelmingly do not indicate a religious affiliation. Almost 83 per cent of junior Other Ranks and almost 90 per cent of Officer Cadets and Midshipmen—most of whom have been recruited since 2019—have no affiliation recorded in Defence’s human resource system.

In stark contrast to Defence figures, the most recent Australian census indicated that in 2021 less than 39 per cent of Australia’s population had no religious affiliation.[3] The difference between the religious affiliation of recruits and that of the nation’s population should rightly be queried; however, buried in the second layer of census data is indication that the differences might not be so large when relevant comparisons are made.

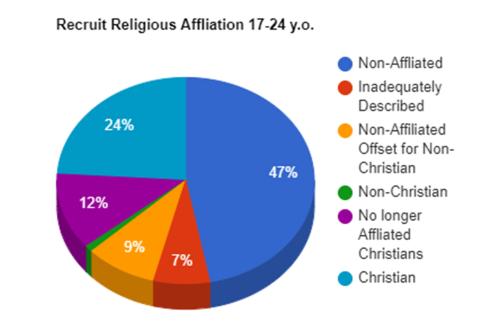

Firstly, the headline figure of 39 per cent only reports the national figure across all age groups. When census data is explicitly examined for the usual target demographic of 17-24-year-olds, almost 47 per cent are not affiliated with a religion[4], considerably higher than in the national population. A further 7 per cent were not stated or inadequately described (parody and unrecognised religions such as Jedi Knights, Pastafarians and others are also in this latter group which is probably less likely to include undeclared genuine Christians). Christian affiliation was 36 per cent and another 10 per cent were affiliated with non-Christian religions. This means that at least 47 per cent, but as many as 54 per cent in this target recruiting demographic of 17-24-year-olds, had no religious affiliation in the first instance.

The remaining difference between the national population and those entering Defence may rest with specific characteristics of recruiting and perceptions of the ADF. For example, non-religious recruits may offset much of the known reluctance of people with religious but non-Christian backgrounds to join Defence. Further, if just one third of applicants who previously described themselves as Christian during their childhood and adolescent years (or had their religion described on their behalf) choose to ‘lose’ their affiliation after enlistment, then this alone would account for most of the remaining difference[5]. Finally, subtleties in Defence’s recruiting methods, which result in recruiting from slightly less religious demographics, may have a small but measurable influence on the religious affiliation of new recruits.

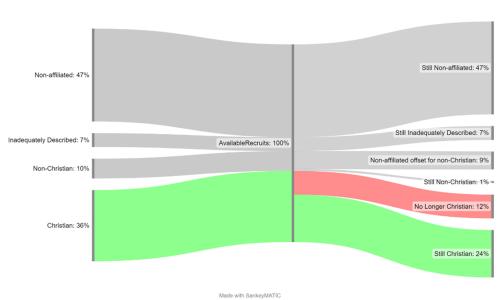

The combination of non-affiliated applicants (47 per cent), inadequately described (7 per cent), offset of non-Christian applicants (estimate of 9 per cent), a proportion of previously described Christians no longer affiliating with Christianity at the point of enlistment (estimate of 12 per cent)[6], and recruiting from less-religious demographics, conservatively aggregates to at least 75 per cent of the applicant demographic maintaining no religious affiliation. This figure is easily derived, entirely plausible, and close to the observed proportion of non-affiliation among the newest ADF members.

The observation that such a large proportion of recruits have no religious affiliation, and that this is simply a characteristic of the demographic from which they are drawn, supports an assessment that the decrease in Defence members’ religious affiliation is set to continue unavoidably until at least 75 per cent have no affiliation by 2030. Increasingly, it seems that a proportion exceeding 80 per cent by 2040 is also now likely. This raises questions around why there is a paucity of uniformed secular wellbeing support options and no apparent plans to change this outside of a small number of Maritime Spiritual Wellbeing Officers in Navy. If a majority of Defence members were religious, as was the case before 2018, and if there were no other suitable and qualified professional occupations that could provide uniformed wellbeing options for serving members, then perhaps an exclusively religious chaplaincy model would at least be understandable. However, this is not the case as recruits are overwhelmingly not religious, the ADF is increasingly not religious, and there are entire alternative professions dedicated to the provision of secular wellbeing services.

The availability of religious Chaplains for the ADF

The recruiting demographic and the emerging cohorts of ADF members has already established the demand for uniformed secular wellbeing practitioners in Defence. With a backdrop of an increasing demand for secular options, the persistent challenges that the ADF has faced in obtaining the necessary numbers of religious chaplains to provide the wellbeing capability has a simple solution through augmentation with secular wellbeing professionals. This section will outline the inevitable continuation of Defence’s inability to recruit religious chaplains into the future. It will be suggested that solutions are required to address the supply of wellbeing practitioners regardless of one’s view concerning the role and appropriateness of religious chaplains in the ADF.

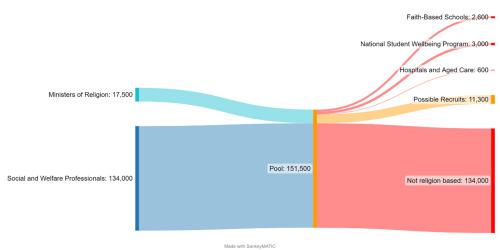

It is difficult to determine the precise number of chaplains in the national community that might be available to the ADF; however, it is possible to make some conservative estimates. The most recent national census indicated that just over 17,500[7] people described their occupation as a ‘Minister of Religion’ as part of the Social and Welfare Professionals occupational grouping.[8] Not all ministers of religion are necessarily in chaplaincy roles or describe themselves as chaplains, just as not all chaplains would necessarily define themselves as a minister of religion. Nonetheless, this figure provides a starting point as to how many chaplains may be in the community. In contrast, an additional 134,000[9] people described themselves as a Social and Welfare Professional alongside counsellors, psychologists, social workers and others. Therefore, ministers of religion comprise just under 12 per cent of the professional grouping. In principle, perhaps 17,500 should be enough to provide chaplains for the ADF and satisfy national demand; however, it is not that simple.

To help explain why 17,500 ministers of religion is not enough to provide for both Defence and the broader needs of the community, it is first worth examining the propensity of the average Australian to join the ADF. It is estimated that only around 13 per cent of regular Australians in the recruiting demographic of 17-to-24-year-olds have both the propensity and base level eligibility (eg, health, aptitude, citizenship, clean criminal history) to join the military before other factors of eligibility, such as specific job qualifications and requirements, are considered.[10] This means that only around 340,000 of the approximately 2.5-2.6 million[11] Australians in this age group are willing and able to enlist in any given year. From this group of approximately 340,000 Australians, the ADF enlists around 5,000 ab initio recruits each year to maintain its full-time strength of 60,000 and has never entirely achieved its recruiting target. These figures for propensity and eligibility diminish rapidly for other age groups where health and domestic circumstances (eg, family, ongoing employment and community relationships) further restrict the applicant pool. In aggregate, this means that less than 2 in every 1000 Australians in the target demographic eventually join the military.

It follows that, if the ADF finds it challenging to recruit 5000 per year from a pool of over 2.5 million people aged 17-24, then recruiting more than a handful of chaplains from a pool of just 17,500 – where only a quarter are under the age of 40 and 5,400 are already over the eligible age – can only be viewed as unsustainable wishful thinking. Even with a genuine intention to fill chaplaincy positions with appropriately qualified ordained ministers (or equivalent) who have a propensity to join the ADF and are eligible to do so, Defence is unlikely to ever fill its recruiting target based simply on the number of ministers of religion in Australia. This scenario has existed for the last several decades and is one that will not change given current policy and selection constraints. It does not even consider that many of the 17,500 do not hold the qualifications to be a Defence chaplain, or the number of chaplains required for Australia’s 2,600 faith-based schools, the 3,000 reportedly needed for the National Student Wellbeing Program (formerly the National School Chaplaincy Program), and those required for about 600 church-owned hospitals and aged care homes, let alone regular community and traditional church-based roles.

To compensate for deficiencies in ab initio recruiting of chaplains, the ADF has turned to various solutions to solve its recruiting dilemma, including use of reservists, retirement age extension waivers, and sponsored education schemes, but even these will have limited enduring effectiveness.

In January 2023 there were around half-a-dozen reservists employed on full-time contracts to fill positions unable to be filled by full-time chaplains—most of whom required a retirement age extension waiver. A further dozen full-time positions were filled by permanent force chaplains requiring an age extension waiver. When those requiring an age extension waiver are combined with the number within two years of Defence’s compulsory retirement age, 20 per cent of all chaplains in permanent force positions exceed or are about to exceed retirement age. Evidently, ADF chaplaincy is now culturally reliant on age extension waivers and, with no succession plans in place, vacancies will either reappear or a fresh waiver cycle will be required. While waivers are a legitimate means to provide capability by exception, they are not an enduring solution and illustrate that Defence’s ability to recruit religious chaplains has exceeded breaking point.[12]

A further initiative to increase the supply of new chaplains is a sponsored education scheme for currently serving ADF members to become chaplains. This scheme has limited effectiveness with just a few participants spread across several cohorts at any given time. Even with small numbers, the ongoing utility of this scheme has a questionable lifespan with the decrease in religious affiliation of serving members likely to reduce the number of interested in-service applicants. It is not speculative to suggest that if the scheme had struggled to attract interest among serving members when Christian religious affiliation exceeded 50 per cent as recently as 2016, it is not going to fare any better when it is just 25 per cent by 2030 or even 20 per cent by 2040.

The ability of the ADF to fill most of its chaplaincy positions in the past has been a testament to recruiting creativity, use of available policy solutions, and engagement of current serving members to consider a role as a chaplain. However, the very existence of these initiatives is evidence of the difficulty in recruiting religious chaplains and they mask the real problems in continuing to rely exclusively on religious chaplains for the provision of wellbeing support. The ongoing recruiting problems are likely to persist into the future and as the effectiveness of the current short-term solutions diminish, growing vacancies are extremely likely at a time when the ADF needs its wellbeing capability the most.

A solution to the likely chaplaincy shortages is straightforward. With a recruiting pool of non-religious wellbeing practitioners almost eight times larger than ministers of religion, and likely to reflect a more favourable propensity and eligibility to join the ADF, expanding Defence’s wellbeing capability to recruit non-religious practitioners to fill the inevitable gaps in religious chaplaincy seems obvious. More importantly, failure to start a Defence-wide program to recruit secular wellbeing practitioners will compromise wellbeing in Defence, an outcome nobody wants.

Conclusion

The imperative for change, driven by the demographics of Australian society and the likely shortage of religious chaplains in the future, is relatively clear and unavoidable. It is almost inevitable that members with no religious affiliation will exceed three-quarters of the total ADF permanent force population by the end of this decade, driven by the newest and future recruits. While the pace of change will slow down in the 2030s, unless there is a dramatic shift in the propensity of young religious Australians to join ADF, it is also inevitable that the proportion of non-religious Defence members will approach and then surpass 80% by 2040 as the current cohorts reach deeper into their careers. In practical terms this means that around 50,000 permanent force members will not have a religious affiliation by 2040.

Simultaneously, maintaining the strength of religious chaplaincy will become increasingly unsustainable. The relatively modest, but already unachievable, recruiting target for chaplains will become even more challenging to obtain year in, year out without significant compromise in qualification and selection criteria. The reasons to continue to exclude non-religious wellbeing practitioners from serving in a uniformed capacity will become increasingly unsustainable and eventually untenable if Defence aims to maintain a uniformed wellbeing capability. To provide fair, reasonable, equitable and adequate wellbeing support, Defence will need to recruit a secular wellbeing capability to support the entire force.

The reluctance of the ADF to consider secular options is time limited and it will soon be confronted with the binary choice of either vacant chaplain positions to the detriment of Defence members, or to open wellbeing positions to secular practitioners. Principled stances on whether or not religious chaplains can provide adequate, unbiased wellbeing and pastoral care to non-religious sailors, soldiers and aviators will become almost irrelevant when the numbers of religious chaplains available to Defence are inadequate. The simultaneity of reduced religiosity in Defence members and decreased supply of religious chaplains should, on the surface, make a decision for Defence to engage secular options simple. Ultimately, the longer Defence procrastinates in its evolutionary transition toward secular wellbeing, the greater it places Defence members at risk of adverse health and wellbeing outcomes.

Biography

Colonel Phillip Hoglin, CSC, graduated from the Royal Military College Duntroon in 1994, having completed a Bachelor of Science (Honours) majoring in statistics at the Australian Defence Force Academy in 1993. In 2004 he completed a Master of Science in Management (Manpower Systems Analysis) through the United States Postgraduate School and in 2012 a Master of Philosophy (Statistics) through the University of New South Wales. He has had several appointments in workforce analysis, policy, strategy, management and recruiting. In mid-2020 Colonel Hoglin transitioned to the Reserves and remains a workforce analyst. Colonel Phillip Hoglin is available on LinkedIN (www.linkedin.com/in/phillip-hoglin)

1 Phillip Hoglin, Losing our Religion: The ADFs Chaplaincy Dilemma, The Forge, 29 January 2021, https://theforge.defence.gov.au/publications/losing-our-religion-adfs-chaplaincy-dilemma. Also published under permission as Secularism and Pastoral Care in the Australian Defence Force, Australian Army Journal 2021, 17(1): 98-111, https://researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/australian-army-journal-aaj/volume-17-number-1-0.

2 Source: PMKeyS as at 1 January 2023.

3 Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021 Census shows changes in Australias religious diversity, ABS, accessed 9 February 2023, https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/2021-census-shows-changes-australias-religious-diversity.

4 Described in the census as Secular Beliefs and Other Spiritual Beliefs and No Religious Affiliation.

5 Neil Francis, Parents answering for children,in Religiosity in Australia: Part 1: Personal faith according to the numbers, Rationalist Society of Australia, 2021: 15-16, https://www.rationalist.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Religiosity-Report-Summary-1.pdf.

6 In a comparison of census results of the same cohort of 7-14-year-olds in 2011 to 17-24-year-olds in 2021, it was found that Christian affiliation fell from 61 per cent to 36 per cent. Or a 41 per cent decrease among the same cohort. A decrease of one-third is conservatively estimated.

7 Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021 Census - employment, income and education. 6-digit level OCCP Occupation, ABS Table builder, accessed on 10 February 2023 describes Minister of Religion strength as 17,532.

8 Described as ANZSCO Unit Group 2722 Ministers of Religion as a unit of Minor Group 272 Social and Welfare Professionals. See Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1220.0 - ANZSCO - Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations, First Edition, Revision 1 , 22 November 2022, Unit Group 2722 Ministers of Religion | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au).

9 Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021 Census - employment, income and education. 4-digit level OCCP Occupation, ABS Table builder, accessed on 10 February 2023.

10 Defence Force Recruiting, Target Demographic Characteristics funnel, (2020), Internal document.

11 Australian Bureau of Statistics, Table 8 Estimated resident population, by age and sexat 30 June, in 2022. Population by age and sex national. 202206 National, state and territory population, June 2022, Released 15 Dec 22. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population/jun-2022

12 While age might not necessarily be a factor in the selection of a wellbeing capability, when chaplains are either Boomers or Gen X, and their dependency is increasingly from Gen Z, there may be some merit in claims that Defence chaplains could be out of touch with the average sailor, soldier or aviator. Currently, the average age of a religious full-time chaplain is 50 (54 in the Reserves), whereas the average age of sailors, soldiers and aviators in the ADF is 30. While a lot can be said for the wisdom of age and experience, there are limitations when the average age gap spans two decades.

Social Mastery

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.