We are in an era where the main instruments of warfare are utilised through non-military means which are more covert with the intent to weaken, destabilise and disrupt.[1] In his speech to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s (ASPI) ‘War in 2025’ international conference, the Australian Chief of Defence Force stated that modern political warfare has emerged. He suggested that the use of political warfare depends on the nature of the state and argued that those states that tended to be more totalitarian have a broader concept of warfare and are typically better able to harness political warfare methodologies that seek to influence, subdue, undermine, overpower, and disrupt. Western democracies, on the other hand, have a narrower concept of warfare in which actions are decisive and political warfare is seen as unpalatable unless it is required against a formidable enemy.[2] The Defence Strategic Update 2020 warns of the increasing use of ‘grey-zone’ activities by some countries in the Indo-Pacific[3] and the need for a strategic policy framework that ‘signals Australia’s ability and willingness to project military power’ to deter actions against us.[4]

This essay will argue that existing theoretical and procedural frameworks for planning and conducting military campaigns do enable Western militaries to adapt to the demands of contemporary political warfare. The introduction and implementation of Whole of Government (WoG) architecture for political warfare would provide better delineation of responsibilities between Western governments and their militaries to counter political warfare.

This essay will first provide an overview of what constitutes contemporary political warfare and what is required to respond to this threat. Second, it will outline the existing theoretical and procedural frameworks for planning and conducting military campaigns, consider whether they enable our ability to adapt to the demands of contemporary political warfare, and discuss the challenges Australia faces when planning for political warfare. Third, it will consider how Government decisions and policies make their way into Defence and how that informs operational planning and the significant effort required by Defence to ensure WoG consideration. Last, it will propose how Australia could better coordinate a WoG response to political warfare through the establishment of an improved WoG framework involving a ‘Political Operation Centre’.

What is Contemporary Political Warfare and what is required to fight it?

George Kennan, a United States diplomat, proposed the following definition in 1948:

‘In broadest definition, political warfare is the employment of all the means at a nation’s command, short of war, to achieve its national objectives. Such operations are both overt and covert.’[5]

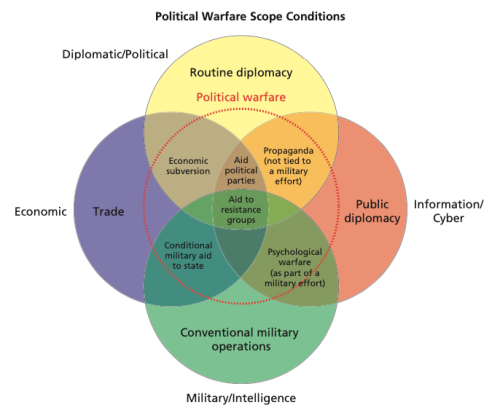

In the modern context, political warfare is the ‘international use of one or more of the traditional implements of national power (diplomatic, information, military and economic) to affect the political composition or decision-making with another state’.[6] It can be conducted by state and non-state actors[7] and can take form as hybrid warfare, grey-zone warfare,[8] psychological warfare,[9] information warfare and cyber warfare. Some key characteristics of political warfare include: being below the threshold of armed conflict; the ability to achieve effects at lower cost; ‘exploiting shared ethnic or religious bonds or other internal seams’; and its detection requiring significant investment and intelligence resources.[10] Figure 1 illustrates the contours of political warfare under the Diplomatic, Information/cyber, Military/intelligence, and Economic (DIME) implements of power construct and some of the possible actions in political warfare where the spheres overlap.

In 2018, Robinson et al conducted an in-depth study on modern political warfare. The study determined characteristics of modern political warfare through analysis of three case studies on Russia, Iran, and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, a non-state actor). Based on the characteristics identified, the study aimed to identify US capability gaps and the ability of the US to respond to these threats. Three of the five key findings from this study identified for the US are as follows: (1) critical information requirements for political warfare threats need to be identified and dedicated intelligence collection and analysis capabilities need to be increased to better detect these threats; (2) an integrated response requires a strategy, a WoG approach led by State, and formulation and coordination of responses with (or through) other governments; and (3) ineffective planning co-ordination and execution of interagency responses were the result of significant gaps in the US Government’s organisation, operational capabilities and practices.[11] In reviewing the volume of literature, the findings in this study are supported and typical for Western militaries, including the ADF, in the planning of joint operations.[12]

Existing Theoretical and Procedural Frameworks for Planning and Conducting Military Campaigns

The Australian Defence Force Publication (ADFP) 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) contains ADF’s existing foundational theoretical and procedural frameworks for planning and conducting military campaigns.[14] As a planning tool it provides guidance on the practice of operational art and is used alongside ADFP 2.0.1 Intelligence Procedures which provides guidance on the intelligence input to the JMAP process.[15] This process is closely aligned with the planning processes of other Western militaries, all of which aim to guide planning teams to ‘focus thinking, enhance collective understanding and develop actionable solutions’ through a ‘sequential series of procedures that translate higher command’s intent and desired end state into concrete missions, tasks, objectives, and lines of operation in a reductionist, linear logic’.[16] This is a proven and effective planning process for the planning and conduct of military campaigns for traditional military operations where there is established doctrine for the range of military operations which contribute to delivering a decisive military effect.

In the context of contemporary political warfare, Western military planning processes such as JMAP are still effective as a theoretical and procedural framework for the planning and conduct of military campaigns. This is because JMAP is a tool which mimics human thinking[17] and hence a planning process that should still derive the missions, lines of operations, objectives, and tasks to achieve the required end state for the political problem set, so long as the problem set is considered correctly, and there is clear articulation of the desired military effect required by government in support of their political agenda. In the case of the ADF, Commander Joint Operations (CJOPS) is given very specific and clear strategic effects to achieve by the Australian Government through the Defence Planning Guidance, which is reviewed and adjusted annually to adapt to the changing environment.[18] When considering the issues arising from political warfare, the challenge for planners is to assess the problem from multiple perspectives before framing it for input into the process to generate a plan.[19]

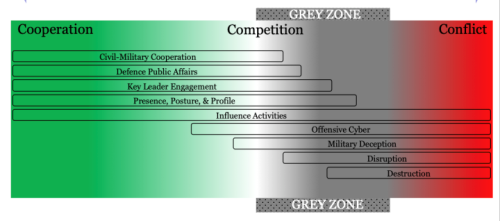

According to CJOPS, joint planning and campaigning in this competitive environment at Headquarters Joint Operations Command (HQJOC), has led to the development of new ADF doctrine which provides insight into ADF effects nested in WoG responses, and the requirement for a deeper and a more integrated approach across the WoG using all elements of national power applied to achieve the required effect.[20] Figure 2, the Competition Prism developed by HQJOC, depicts the spectrum of relationships with competitors and partners for campaigning in competition. Though contemporary political warfare is on the increase in the region, it also creates opportunities for like-minded partners to cooperate and establish bilateral and multilateral agreements and treaties in an attempt to change the strategic environment to achieve desired strategic outcomes.[21]

Defence capabilities and activities contribute to Australia’s national power. These actions range from establishing Australia’s national legitimacy to deterring an adversary’s course of action. Figure 3 depicts the spectrum of military activities conducted by the ADF. It is necessary that the ADF contributes to the efforts made by the Australian Government to avoid conflict by developing ways and means to collaborate with like-minded partners in the region to defend and promote our common interests. The ADF is prepared to illuminate and expose grey-zone activity and maligned competition and confront it with action below the level of conflict.[23] According to Air Commodore Hombsch, the ADF’s relationship with competitors can change depending on the environment, and it is possible to both cooperate and collaborate in competition across all elements of national power through the DIME construct; it is the aim of the ADF to draw our partners and competitors into the collaborative space.[24]

The development of the Competition Prism and the way Defence thinks about its activities in the cooperation and conflict spectrum demonstrates that the ADF is refining our existing theoretical and procedural frameworks to adapt to the demands of the changing environment, which is seeing an increase in coercion and grey-zone activity (political warfare). In 2021, there was overhaul of warfighting doctrine introducing some tailored for political warfare such as the ADF Philosophical level operation doctrine (ADF-P-3) Campaigning in Competition and ADF Integration level operation doctrine (ADF-I-3) Cyberspace Operations from the operations series. These doctrines have only recently been developed and are available through the ADF Doctrine library webpage.[26]

This is not to say that Western militaries have adapted seamlessly to the demands of modern political warfare. While the planning process still works and allows Western militaries to deliver the effects required in support of the political agenda; the problem is that modern political warfare requires integration between inter-government agencies and a WoG approach to fully understand the political problem set so that an appropriate plan can be developed. Hence the problem in this instance is not with the planning process but the lack of a WoG architecture to enable governments to respond to political warfare proactively. An example of this is that while there are embedded Other Government Agencies (OGA) in HQJOC, operations with OGAs still poses challenges for HQJOC as there is no disciplined approach to contingency planning across the WoG. Operations involving OGAs (such as the recent Afghanistan Non-combatant Evacuation Operations) could be executed more effectively if there was better collaboration with OGAs during contingency planning.[27]

From a delineation of responsibility perspective, the use of the term ‘political warfare’ is misleading as the word ‘warfare’ implies that political warfare requires either a military solution or the military to take the lead in its resolution. Keeping in line with current ADF terminology, a more appropriate choice of word in place of ‘warfare’ might be political ‘competition’. Warfare is the business of the military, and the ADF is well versed in planning and campaigning activities to counter threats. It is a logical choice for the military to take the lead in countering political warfare, however, one could argue that political competition is a political problem which the government needs to resolve through exercising a range of national instruments of power. Looking through this lens, the government should be coordinating the WoG response to political competition, directing the military to deliver the effects required through military operations to support the government in their response to political competition. The military should only play an active role in combating political competition when military capability is threatened or compromised through activities such as cyber-attacks on military systems or when the adversary’s military actions are offensive but below the threshold of conflict.

Strategic Policy to Operational Planning

In Australia’s Federal Government system, decision making lies with the Cabinet, which is chaired by the Prime Minister (PM). The National Security Committee of Cabinet (NSC) is a sub-committee of Cabinet with decision-making powers for matters relating to national security.[28] The NSC has remit to decide on the ADF’s use of force or to deploy the ADF should Australia face a significant security challenge. Lodgement of routine submissions for consideration by Cabinet and NSC follow a strict process with significant lead time.[29] This process ensures submissions go through rigorous consultation across relevant Government departments before they are presented to committee, enabling fully informed decisions to take place.[30] Though the process is seen to be robust, one can say that it is not a dynamic process under normal circumstances, noting the long lead time in the preparation of a submission before it can be considered as an agenda item. However, should the strategic circumstances require, the NSC is flexible enough to meet more regularly and move quickly in the event of a crisis. Agenda items range from long-term documents such as strategic policy (eg Defence White Paper), activities such as the Pacific Step-Up Program, and specific operational activities such as regional engagement activities and the recent Afghanistan evacuation.[31]

Government direction works its way into the Defence strategic level through the Military Strategic Planning Division (responsible for long-term planning) and Military Strategic Commitments Division (responsible for immediate response to five-year planning). These organisations, in conjunction with Strategic Policy and International Policy Divisions, develop, coordinate and provide guidance for Defence’s contribution to the national effort and strategy; developing military ways and means to meet government objectives. Assurance that Defence strategic planning meets government’s objectives requires significant networking across the WoG by Defence staff at the strategic level. Once developed, Defence strategic end states filter down to HQJOC for operational planning. In a competitive political environment, ADF is required to contribute effectively and creatively to the WoG efforts across the spectrum of activities depicted in Figure 3.[32] The ADF, like all other Western militaries, is proactive in operational planning and contingency planning; the current process and framework is effective primarily because Defence makes a significant effort in interpreting what government policies mean for Defence and involving OGAs in its scoping and framing of the problem at the strategic and operational level.

How Could We Better Coordinate a WoG Response to ‘Political Competition’?

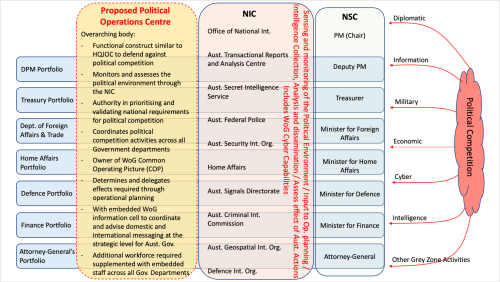

It is proposed that a more effective WoG approach to competing in political competition would see an overarching body taking the lead to coordinate political competition activities across all government departments and fulfil the function of prioritising validated national requirements for political competition. Government direction to Defence and all OGAs to counter political competition would be derived from this process. If this governing body was appropriately resourced with a newly established workforce as well as embedded personnel across all Government departments, a ‘Political Operations Centre’ with a similar functional construct to HQJOC could be established. Personnel most suited for this established workforce would be those with operational experience who have worked at the strategic levels of government. Figure 4 depicts a theoretical relationship between the proposed Political Operations Centre with the existing WoG construct.

This Political Operations Centre could be a statutory authority within the Home Affairs portfolio and responsive to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet or NSC, consistently monitoring and assessing the political environment. This would enable better collaboration between departments to consider political competition more holistically as a system, rather than viewing it through a departmental lens with its inherent biases. Consideration of the system as a whole is important because actors within the political competition system will likely have linkages and interdependencies; an action by the Australian Government may not necessarily have the desired effect if the entire system is not understood or engaged. This emphasises the importance of intelligence and security services that are critical enablers in political competition.

In Australia, the Office of National Intelligence (ONI) is accountable to the PM for the management of the National Intelligence Community (NIC) at the enterprise level. Its role is to ‘ensure Australia has an agile, integrated intelligence enterprise that will meet the challenges of Australia’s evolving security environment’.[33] The NIC work to ‘collect, analyse and disseminate intelligence … in accordance with Australia’s interests and national security priorities’ set out by ONI.[34] Though Australian intelligence seems robust, in reality and from experience at the working level, information is often difficult to find due to the nature of the agencies tending to compartmentalise their information or as a result of agencies using different intelligence databases and poor and inconsistent data management. It’s important to note that, although the ONI assumed the role of managing the NIC in 2017, it is the author’s opinion that their processes are still being refined and the WoG approach to intelligence has yet to be cemented.

The fact that there is not one Common Operating Picture (COP) used across the WoG is evidence of the limitation of Australia’s WoG approach. If the Australian Geospatial-Intelligence Organisation was to take the lead in managing a WoG COP, where each security agency was responsible for the data on allocated COP layers, then the NSC—as the primary security decision-making apparatus for government—would have a more complete picture of what we know about the operational environment. Access to compartmented intelligence and classified data could easily be managed through organisational and individual privileges to those sensitive layers. The ability to visualise WoG intelligence and information through a multi-agency layered COP not only provides a comprehensive operational picture but highlights instances where there is duplication of effort between agencies and where there are anomalies or discrepancies which require further investigation. The incorporation of analysed intelligence layers may have the potential to assist in understanding the relational aspects of the political ecosystem.

If a Political Operations Centre existed, the ONI would perform the intelligence function providing direction to the NIC for the provision of critical intelligence input to the political operations planning process. A Political Operations Centre would take the lead on ‘political competition’ contingency planning across WoG, and strategic objectives that are produced by this process could inform Defence planning. In essence, there would be a clear delineation of the government’s responsibility in political competition, the function and responsibilities of each government agency and the responsibility for Defence to be ‘conflict ready’ and to perform activities across the cooperation-conflict spectrum in support of the political competition effort. The recent establishment of the Office of the Pacific in the Pacific Step-Up Program has demonstrated to be effective;[35] using that construct as a template, a similar office could be established for other regions of interest with direct input to political operations.

Conclusion

Contemporary political warfare that aims to weaken, destabilise and disrupt is on the increase. Studies show that in this new environment, intelligence and strategies involving a WoG approach, with clear delineation of authorities, are required to fight this new threat more effectively. JMAP is the theoretical and procedural framework for planning and conducting military campaigns in the ADF, much like the processes used by other Western militaries. These processes are simply planning tools that mimic human thinking. If applied to political warfare, they are still able to derive the missions, lines of operations, objectives and tasks to achieve an end state for a political problem—so long as the problem has been considered thoroughly and in full context. For this reason, the existing theoretical and procedural framework for planning and conducting military campaigns does enable our ability to adapt to the demands of contemporary political warfare.

Though there is currently no formal WoG architecture to respond to political warfare, Defence places significant effort to engage with OGAs in the strategic and operational planning process to ensure there is WoG consideration in all their activities in shaping the Australian strategic environment. Whilst this approach is currently working and considered a robust process in dealing with security threats, it is proposed that the establishment of an overarching organisation (or Political Operations Centre) across all government agencies to coordinate a WoG response to political warfare would be beneficial and better delineate government and military responsibilities in this emerging threat.

ADFHQ. ‘ADF Doctrine Library’. Accessed October 10, 2021. drnet/vcdf/ADF-Doctrine/Pages/ADF-Doctrine_Library.aspx#five_series.

Australian Government. ‘National Security Committee’. Australian Government Directory. Accessed October 15, 2021. https://www.directory.gov.au/commonwealth-parliament/cabinet/cabinet-committees/national-security-committee.

Babbage, Ross. ‘Winning Without Fighting: Chinese and Russian Political Warfare Campaigns and How the West Can Prevail: Volume I’. Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2019.

Barno, David, and Nora Bensahel. ‘Falling into the Adaptation Gap’. War on the Rocks. Washington DC, September 2020.

Bilton, Greg, and David Hombsch. ‘Joint Operations Planning Presentation To Australian Command & Staff Course’. Canberra: Australian War College, 2021.

Boot, Max, and Michael Doran. ‘Political Warfare’. Council on Foreign Relations, October 9, 2013.

Bosio, Nick. ‘Strategic Planning - Military Strategic Plans Division’. Canberra: Australian War College, 2021.

Caliskan, Murat. ‘Modern Political Warfare: Current Practices and Possible Responses’. The RUSI Journal 164 (February 23, 2019): 84–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2019.1621490.

Chipman, Robert. ‘National Security Decision Making’. Canberra: Australian War College, 2021.

Chivvis, Christopher S. ‘Hybrid War: Russian Contemporary Political Warfare’. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 73, no. 5 (September 3, 2017): 316–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2017.1362903.

Commonwealth of Australia. ‘2020 Defence Strategic Update’. Commonwealth of Australia, 2020.

Copley, Gregory R, ed. ‘21st Century Political Warfare’. Defense & Foreign Affairs Strategic Policy 38, no. 7 (2010): 3,23.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Cabinet Handbook. 14th ed. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia 2020, 2020. https://doi.org/978-1-925364-36-1.

Dewit, Daniel. ‘The Inauguration of 21st Century Political Warfare: A Strategy for Countering Russian Non-Linear Warfare Capabilities’. Small Wars Journal. McLean, Virginia, November 2015.

Field, Chris. ‘Five Ideas: On Planning’. The Cove, 2020.

Jackson, Aaron. ‘Centre of Gravity Analysis “Down Under” The Australian Defence Force’s New Approach’. JQF 84 1st Quarte (2017).

Joint Doctrine Directorate. ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process. Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1. 2 Al3. Directorate Publishing, Library and Information Services, 2019.

Jones, Seth G. ‘The Return of Political Warfare’, 2018.

Kelly, Brigadier Justin, and Michael James Brennan. ‘Alien: How Operational Art Devoured Strategy’. Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2009.

Khomko, Konstantin. ‘A Nation Needs More than a DIME’. Defence.Info, 2019. https://defense.info/williams-foundation/2019/04/a-nation-needs-more-than-a-dime/.

Monk, Jeremiah. End State: The Fallacy Of Modern Military Planning’. Alabama, 2017.

Nicholson, Brendan. ‘ADF Chief: West Faces a New Threat from “Political Warfare”’. The Strategist. Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, June 2019.

Office of National Intellegence. ‘ONI Overview’. Accessed October 16, 2021. https://www.oni.gov.au/overview.

Office of National Intellegence. ‘The National Intelligence Community’. Accessed October 16, 2021. https://www.oni.gov.au/national-intelligence-community.

Pronk, Danny. ‘The Return of Political Warfare’. Strategic Monitor 2018-2019. Hague, 2019.

Robinson, Linda, Todd C Helmus, Raphael S Cohen, Alireza Nader, Andrew Radin, Madeline Magnuson, and Katya Migacheva. The Growing Need to Focus on Modern Political Warfare. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation PP - Santa Monica, CA, 2019. https://doi.org/10.7249/RB10071.

Robinson, Linda, Todd C Helmus, Raphael S Cohen, Alireza Nader, Andrew Radin, Madeline Magnuson, and Katya Migacheva. Modern Political Warfare: Current Practices and Possible Responses. RAND Corporation PP - Santa Monica, CA, 2018. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1772.

Shaw, Martin. ‘The Contemporary Mode of Warfare? Mary Kaldor’s Theory of New Wars’. Edited by Mary Kaldor, Basker Vashee, Ulrich Albrecht, and Geneviève Schméder. Review of International Political Economy 7, no. 1 (August 29, 2021): 171–80.

1 Murat Caliskan, 'Modern Political Warfare: Current Practices and Possible Responses', The RUSI Journal 164 (February 23, 2019): 1, https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2019.1621490.

2 Brendan Nicholson, 'ADF Chief: West Faces a New Threat from "Political Warfare"', The Strategist (Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, June 2019).

3 Commonwealth of Australia, 2020 Defence Strategic Update, Commonwealth of Australia, 2020, 12,.

4 Commonwealth of Australia, 3.

5 Max Boot and Michael Doran, 'Political Warfare', (Council on Foreign Relations, October 9, 2013), 2.

6 Danny Pronk, 'The Return of Political Warfare', Strategic Monitor 2018-2019 (Hague, 2019), 1.

7 Linda Robinson et al, Modern Political Warfare: Current Practices and Possible Responses (RAND Corporation PP - Santa Monica, CA, 2018), 220, https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1772.

8 Caliskan, 'Modern Political Warfare: Current Practices and Possible Responses', 2.

9 Gregory R Copley, ed, '21st Century Political Warfare', Defense & Foreign Affairs Strategic Policy 38, no. 7 (2010): 1.

10 Pronk, 'The Return of Political Warfare', 1.

11 Linda Robinson et al, The Growing Need to Focus on Modern Political Warfare (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation PP - Santa Monica, CA, 2019), 1, https://doi.org/10.7249/RB10071.

12 Greg Bilton and David Hombsch, 'Joint Operations Planning Presentation To Australian Command & Staff Course'. (Canberra: Australian War College, 2021).

13 Robinson et al, Modern Political Warfare: Current Practices and Possible Responses, 7.

14 Joint Doctrine Directorate, ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process, Australian Defence Force Procedures 5.0.1, 2 Al3 (Directorate Publishing, Library and Information Services, 2019), 1–1.

15 Joint Doctrine Directorate, 1–2.

16 Chris Field, 'Five Ideas: On Planning', The Cove, 2020.

17 Nick Bosio, 'Strategic Planning - Military Strategic Plans Division'. (Canberra: Australian War College, 2021).

18 Bilton and Hombsch, 'Joint Operations Planning Presentation To Australian Command & Staff Course'.”

19 Bosio, 'Strategic Planning - Military Strategic Plans Division'.

20 Bilton and Hombsch, 'Joint Operations Planning Presentation To Australian Command & Staff Course'.

21 Copley, '21st Century Political Warfare', 1.

22 Bilton and Hombsch, 'Joint Operations Planning Presentation To Australian Command & Staff Course', 2.

23 Bilton and Hombsch, 'Joint Operations Planning Presentation To Australian Command & Staff Course'.

24 Bilton and Hombsch.

25 Robert Chipman, 'National Security Decision Making'. (Canberra: Australian War College, 2021), 3.

26 ADFHQ, 'ADF Doctrine Library', accessed October 10, 2021, drnet/vcdf/ADF-Doctrine/Pages/ADF-Doctrine_Library.aspx#five_series.

27 Bilton and Hombsch, 'Joint Operations Planning Presentation To Australian Command & Staff Course'.

28 Australian Government, National Security Committee, Australian Government Directory, accessed October 15, 2021, https://www.directory.gov.au/commonwealth-parliament/cabinet/cabinet-committees/national-security-committee.

29 Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Cabinet Handbook, 14th ed. (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia 2020, 2020), 33, https://doi.org/978-1-925364-36-1.

30 Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 19–20.

31 Chipman, National Security Decision Making.

32 Chipman.

33 Office of National Intelligence, 'ONI Overview', accessed October 16, 2021, https://www.oni.gov.au/overview.

34 Office of National Intelligence, 'The National Intelligence Community', accessed October 16, 2021, https://www.oni.gov.au/national-intelligence-community.

35 Bilton and Hombsch, 'Joint Operations Planning Presentation To Australian Command & Staff Course'.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.