We must learn to defend, delay, attack and manoeuvre in cyberspace, just as we might on the land, sea or air and all together at the same time. Future war will always include a cyber dimension and it could become the dominant form.

General Sir David Richards[1]

False Strike: A very short war story

Reconnaissance elements of the 2nd Battalion disembarked from HMAS Canberra in darkness, the vulnerability of their small boats counterbalanced by the guns of the distant destroyer and frigate. Somewhere to their north a submarine, Triton UAV and second frigate were working a coordinated patrol pattern screening the northern approaches to Objective Monash. Maritime Patrol Aircraft had been committed elsewhere. None of this gave the soldiers being jolted about in the rough chop as much comfort as knowing two pairs of Joint Strike Fighters would be on station in exactly two minutes. The jets had been queued in response to a potential threat to the ships, but could be called on by the reconnaissance platoon for close air support if the need arose.

The lead boat was almost in the surf break when the north-western horizon lit up like the first rays of dawn light. The platoon commander thought he could make out the silhouette of a ship’s bridge low on the horizon. Thirteen seconds later the sound of distant explosions reached him, before being replaced by the thrum of helicopter rotors. Members of the recon platoon scanned the horizon through their night vision goggles; no one saw the pair of attack helicopters until they had opened fire. The lead boat was hit, soldiers were overboard and bobbing wounded in the surf break. Ineffective small arms fire lashed through the air in the general direction of the enemy helicopters. The Joint Terminal Air Controller spoke calmly but loudly into her handset while the helicopters were circling low over the beach, lining up for a second pass. ‘CAS is on its way!’ she tried to shout over the noise of battle. An F-35 came in low and fast, the exact position of friendly forces known by the secure transmission of GPS established coordinates through the battle management system. First one helicopter erupted in a fireball and then the second spiralled smoking out of the air. The scream of the jet’s engines faded as it sped out of sight.

Long after securing the beachhead, the soldiers learnt the explosions they had witnessed on the horizon had come from four anti-ship missiles, one of which hit the frigate causing significant casualties and damage. The destroyer had managed to defend against the others. The missiles had been launched from a modified cargo ship, well beyond the horizon. One pair of F-35s had destroyed the enemy’s covert strike platform with a salvo of anti-ship missiles, but not before the two helicopters had slipped away flying undetected along the wave tops.

The lead elements of the Joint Task Force had achieved the immediate physical objective. Nevertheless, the tide of the conflict was rapidly turning against Australia. A glitch with the battle management system was creating confusion up and down the chain of command. The Task Force was being blamed for an inexplicable power outage in a city nearby to Objective Monash. Angry social media posts had rapidly escalated to scathing media reports and angry host-nation press releases. Enemy propaganda, filmed in ultra-high definition from a small fishing vessel and appearing to show Australian jets destroying a cargo ship, had been aired before the planes had even returned to base. The adversary’s state-owned news agency married the footage with Automated Identification System data, touting it as unequivocal proof of Australian war crimes. A grainy photo of a burning warship had been posted to Twitter from a very senior Royal Australian Air Force Officer’s account. The post contained an apology for a friendly-fire incident and a statement of immediate resignation—the gentleman had not used Twitter since War College. Canberra awoke to outrage being spread at home and across the globe. Meanwhile, the deployment of the sustainment of Task Force had been beset by mishap, with the Defence Force being blamed for a catastrophic fuel leak into Darwin Harbour and the collision of two freight trains at Townsville Port. Despite inflicting the first physical blow against the enemy’s advance across the ocean, Australia now faced defeat through the information environment and cyberspace.

Future conflicts will not be won in cyberspace, but they can most certainly be lost there. While this statement appears self-contradictory, deeper consideration shows it to be a paradox of the information age. Success in conflict will of course remain dependent on states’ ability to apply the instruments of national power against their adversaries. The Joint Force must be capable of exercising military power, the ultimate expression of which is decisive joint manoeuvre, across the physical domains. However, adversary actions in cyberspace have the potential to erode the political will, moral authority, domestic and international support, and even dislocate the forces required to legitimately and effectively exercise military power. Future conflict is cyber-enabled conflict. The Joint Force must be trained and prepared to fight in and through cyberspace in parallel to joint manoeuvre to be victorious.

Success in cyber-enabled conflict will not be solely dependent on the quality and quantity of cyber-force elements, but equally so on the ability of the Joint Force to understand the environment in sufficient detail to seize opportunities and protect vulnerabilities. These tasks transcend any single staff area; doctrine, training, structures and processes must be adapted to meet the growing challenges of cyber-enabled conflict.

Cyberspace More than a Communications Domain

To be able to fight in and through cyberspace, the Joint Force must first understand what it is and how it interacts with the physical domains and information environment. Current Australian Defence Force (ADF) practice places the responsibility for this on the J6 staff, although this is not reflected in doctrine. While there is a vital role for the communications community, understanding the characteristics of cyberspace and the nature of cyber-enabled conflict must become a headquarters responsibility that spans all staff branches. While the Joint Force Commander and principal staff officers do not necessarily need to understand the technical workings of cyberspace, they must have a conceptual framework for understanding how actions in and through cyberspace may affect joint operations.

A domain concept is a fitting framework to enable the Joint Force Commander’s visualisation of cyber-enabled conflict. But no singular appropriate domain concept currently exists in Australian doctrine. In publicly available Australian, UK and US strategic documents and doctrine there are no fewer than eight domain models containing some variation of the cyber and/or information domains.[2] These ‘domains are inconsistent between and within national doctrines’.[3] This inconsistency, especially within ADF joint doctrine, is detrimental to the Joint Force’s ability to understand cyber terrain and cyber-enabled conflict. Deciding on a single and unifying domain model for employment across ADF doctrine is a relatively easy first step in increasing the Joint Force’s preparedness to fight a cyber-enabled war.

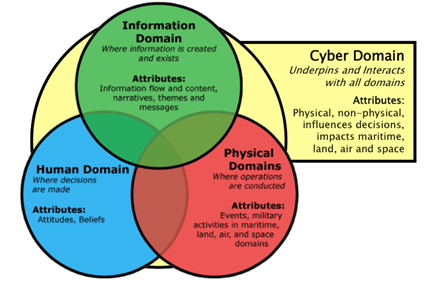

The challenge then becomes deciding on, or creating, the domain model to be implemented. Ormrod and Turnbull’s cyber ‘conceptual framework’ model is almost certainly the most accurate and detailed representation of the complexity of cyberspace. But detail and accuracy does not necessarily equate to utility for the Joint Commander and their staff. It is an oft-quoted (and misquoted) generalisation that, ‘essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful’.[4] Rather than focus on producing the most precise and technically correct domain model, the ADF should instead choose the domain model that is most useful to the task of understanding and visualising cyber-enabled conflict. Thereby, a model—such as that presented by Morgan and Thompson[5], or Wardrop[6]—in which cyberspace is represented as a domain, interacting with or even underpinning the other domains, strikes an appropriate balance between accuracy and complexity while maintaining ease of understanding and application.

Applying either of the domain models in Figure 1 to joint combat demonstrates that understanding cyberspace, and planning and executing operations in and through cyberspace, must not be a task confined to the J6 staff or a niche team within the Joint Force staff —threats and opportunities in and through cyber domain must be appreciated by all staff branches if the Joint Force is to succeed in cyber-enabled conflict.

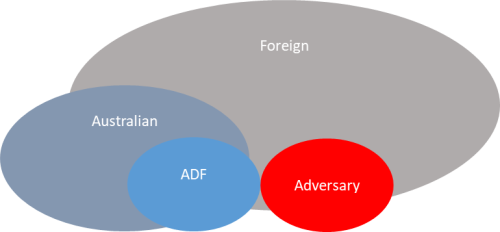

Threats in and through cyberspace come from a broad range of actors—cyber-threat actors can be broadly categorised as state actors, state proxies, and non-state actors.[7] These actors have varying levels of capability to affect physical and non-physical targets in and through the cyberspace. Figure 2 shows potential targets through cyberspace and potential targets in cyberspace. The targets in the centre of the diagram may either have components in the cyber domain or they may be vulnerable to attack through the cyber domain.[8]

Much of the cyberspace terrain these targets exist in is beyond the control and visibility of the Joint Force and even the ADF communications enterprise as a whole. Nevertheless, the protection of friendly targets and exploitation of adversary targets must be fully appreciated in order for the Joint Force to succeed in cyber-enabled conflict.

Understanding Cyber Terrain

To properly appreciate the threats and opportunities it is necessary to further divide the cyberspace, and to understand responsibilities in each cyber terrain segment. US joint doctrine[9] defines ‘blue’ cyberspace as those areas of cyberspace the US Department of Defense is or may be responsible for protecting; ‘red’ cyberspace as ‘those portions of cyberspace owned or controlled by an adversary or enemy’; and ‘gray’ (grey) cyberspace as the remaining portions of cyberspace that do ‘not meet the description of either ’blue’ or ’red’.[10]

Capabilities essential to the mobilisation, deployment and sustainment of the Joint Force are reliant on activities in and through grey cyberspace—consider the reliance on the industrial support base, strategic communications[11], health, transport and energy sectors in preparing for, and engaging in, armed conflict. While these examples constitute grey cyberspace from a strictly ADF perspective, the Australian Government frames the cyber security and defence of critical infrastructure, essential services, and even small to medium enterprises, as a whole-of-nation responsibility.[12] As such, we may assume the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC), as a part of the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD)[13], views Australian Government networks, critical infrastructure, and large organisations as blue cyberspace. To adequately plan, deconflict actions and request support, the Joint Force must make a distinction between ADF blue cyberspace and those networks and systems the Australian Government considers blue cyberspace. For the purposes of this paper, we will frame cyber terrain from a Joint Force perspective and employ the following definitions:

- ADF blue cyber terrain: ADF-owned networks and systems

- Australian blue cyber terrain: Non-ADF Australian Government, critical infrastructure and business networks and systems

- Foreign grey cyber terrain: Non-adversary-owned networks and systems

- Red cyber terrain: Adversary-owned networks and systems

The Joint Force cannot be reasonably expected to appreciate the gamut of threats and opportunities present across the spectrum of blue to red cyberspace without significant support. Equally importantly, the Joint Force must understand the operational (not just ICT security) risk resulting from threats to blue and grey cyberspace throughout each phase of operations.

ADF Blue Cyber Terrain

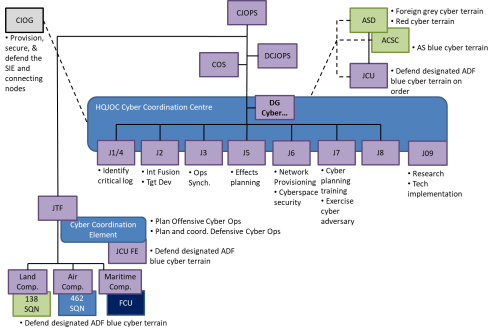

The responsibility for ADF blue cyber terrain does not rest with any one element of the ADF alone. Chief Information Officer Group (CIOG) is responsible for the provisioning, cyber security and defence of the Single Information Environment (SIE), which itself is ‘one of the largest ICT networks in Australia’.[14] Groups and Services have a plethora of other systems and networks for which they are responsible for, at least up until force assignment. After force assignment the Joint Force, supported by Joint and Single Service cyber-force elements, must assume responsibility for cyber security and defence of assigned networks and systems; however, this is not a task the Joint Force can succeed at alone. The Joint Force’s networks and systems should not be viewed as stand-alone, instead they must be appreciated as interconnected ‘systems-of-systems’. While the Joint Force’s signals/communications elements must bear primary responsibility for network provisioning and cyber security,[15] effective Defensive Cyberspace Operations[16] will be dependent on synchronising, coordinating and collaborating across multiple stakeholders – foremost being CIOG for defence of the SIE’s nexus with deployed networks, and Joint and Single Service cyber force elements for Defensive Cyberspace Operations at the Joint Task Force and component levels. The Joint Force must be able to synchronise and coordinate these activities in ADF blue cyber terrain by phase, across levels of command and with logistics, effects, information activities and manoeuvre to be successful in cyber-enabled conflict.

Australian Blue Cyber Terrain

The ACSC ‘leads the Australian Government’s efforts on national cyber security’.[17]

The ACSC monitors cyber threats targeting Australian interests and, when a serious cyber incident occurs, leads the Australian Government’s response: providing advice and assistance to remediate and mitigate the threat and strengthen our nation’s defences.[18]

The Joint Force must be able to leverage the knowledge and expertise of the ACSC to identify threats to Australian blue cyber terrain that may pose risk to Joint Force logistics, information activities, effects and manoeuvre. Furthermore, responses to these threats will almost certainly be beyond the capabilities, scope and authorities of cyber-force elements assigned to the Joint Force, requiring coordination with, and support from, the ACSC. The Joint Force must have structures and processes in place to not only identify the targetable critical vulnerabilities in Australian blue cyber terrain that present unacceptable levels of operational risk, but to also adapt the Joint Force’s physical activities and request external cyber support to mitigate those risks.

Grey Cyber Terrain

Grey cyber terrain may be utilised by the adversary as an avenue to gain logical[19] proximity to ADF blue cyber terrain and Australian blue cyber terrain, and for obfuscation of the adversary’s offensive cyber operations. Furthermore, adversaries may attempt to disrupt Joint Force operations by exploiting and attacking relatively poorly secured and defended third-nation systems and networks. Consider, for example, the potential opportunities inherent in an adversary’s infiltration of a host-nation’s government, national telecommunications and industrial networks. Understanding what the adversary is doing in grey cyber terrain, defending against those actions, and where necessary countering them, will prove vital to the success of Joint Force operations. ‘Situational awareness of adversary activity in grey and red cyberspace relies heavily on cyberspace exploitation and SIGINT, but contributions can come from all sources of intelligence.’[20] The Joint Force should not be expected to solely collect against, analyse and mitigate adversary actions in grey cyber terrain; however, the Joint Force Commander and staff must appreciate the impacts on operational risk and have a mechanism in place for requesting appropriate support in response. There is a wide array of potential responses—diplomatic, economic, legal, support to third-nation cyber security, Defensive Cyberspace Operations-Response Actions[21], etc—beyond the Joint Force’s integral capabilities. The Joint Force must have robust links to ASD for strategic SIGINT support to understand the environment and, where necessary, to request application of offensive cyber capabilities[22] to support Joint Force operations.

Red Cyber Terrain

Red cyber terrain is controlled by the adversary ‘to the exclusion of others’.[23] The Joint Force should consider this to include not only the adversary’s cyber warfare systems, but also their military networks and systems, and potentially government and industrial networks too. Fundamentally, the Joint Force must be able to identify targetable critical vulnerabilities in red cyberspace, with the view of protecting its own centre of gravity and undermining the adversary’s centre of gravity. Achieving this degree of appreciation while reliant on SIGINT[24] requires the fusion and analysis of all sources of intelligence in combination with a thorough understanding of the Joint Force’s own operational plan. This should be viewed as an integrated intelligence and operations function—supported by communications, logistics, information activities and effects—similarly to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.[25] To understand, exploit[26] and attack[27] red cyber terrain, the Joint Force must be capable of leveraging the expertise, capabilities and authorities of ASD. However, the Joint Force should not be constrained to only ‘fighting cyber with cyber’ , but must also consider, where appropriate, leveraging physical effects against red cyber terrain to achieve decisive effects. As such, the planning of Offensive Cyberspace Operations must not be conducted in isolation from other effects and information activities planning processes.

Cyberspace Security vs. Cyber-Enabled Warfare

To fight and win a cyber-enabled conflict, the Joint Force must have a strong foundation of cyberspace security. Cyberspace security is network-specific and threat-agnostic; it is the actions undertaken within blue cyber terrain to prevent unauthorised access, exploitation or damage to the networks, systems and data stored within.[28] Sound cyberspace security practice complies with the Information Security Manual and the ACSC cyber security mitigation strategies.[29] It is somewhat analogous to ‘security’ and ‘depth’ in land combat Area Defence, whereas the employment of Defensive Cyberspace Operations force elements may be considered equivalent to the ‘Counter-penetration’ and ‘Counter-attack’ force. The responsibility for maintaining a solid cyberspace security foundation rests with the commander of the organisation provisioning the network or system -- the J6 in a Joint Task Force setting and CIOG for the SIE. Joint or Single Service Defensive Cyberspace Operations elements conducting threat-specific, intelligence-led cyber defence are reliant on the sensors and controls deployed in blue terrain under cyberspace security activities to identify abnormal activity that can be attributed to a threat actor. Without sufficient cyberspace security controls in place, Defensive Cyberspace Operations elements will be unable to distinguish adversary actions from poor ICT configuration and system errors.

Despite the obviously complementary nature of cyberspace security and Defensive Cyberspace Operations, there may be times when cyberspace security and cyber-enabled warfare objectives are in conflict. For instance, the adversary’s ongoing compromise of a network of low operational importance may be tolerable to the Joint Force Commander if the collection of cyber threat intelligence from that network enables a decisive Response Action to be taken against the adversary. Even more controversially, it is imaginable that a course of action may call for the lowering of cyberspace security controls on a specific system to create an attractive target for an adversary as either an act of deception, or delay, or to enable disruption through Response Actions. A decision to deliberately erode own-force cyberspace security controls, even on single specific systems, is contrary to the Information Security Manual and anathema to those responsible for its implementation. Nevertheless, to succeed in cyber-enabled conflict, the Joint Force must be able to consider such possibilities; and even the consideration of such is likely to require a separation of roles between those responsible for network provisioning and cyberspace security and those responsible for planning and coordinating cyber-enabled warfare. Beyond which the coordination of cyber deception activities is likely to require authorisation and synchronisation with manoeuvre, effects and information activities at the highest levels of operational command and the support of strategic agency SIGINT and Offensive Cyberspace Operations capabilities. The Joint Force must have the structures and processes in place to deal with these issues before entering into a cyber-enabled conflict.

Preparing for Cyber-Enabled Conflict

While Joint Capability Group, CIOG, and the individual Services focus on growing cyberspace capabilities, particularly Defensive Cyberspace Operations elements,[30] manoeuvre commanders and their staffs must rapidly come to terms with the opportunities and threats inherent in cyber-enabled conflict if the Joint Force is to successfully face the security challenges of the 21st century. Immediate measures should include:

- Updating all Joint and Single Service planning, operations, intelligence and communications doctrine with a singular domain model to enable visualisation of actions in and through the cyberspace.

- The inclusion of a detailed cyber terrain model in relevant planning, operations and intelligence doctrine, and the inclusion of cyber domain planning considerations across all relevant Joint and Single Service Doctrine.

- Implementation of a sovereign Cyber Operations Planning Course[31] as an immediate stopgap measure while doctrine is updated and incorporated into all joint professional military education and office training continuum courses.

- Recognition that planning and executing cyber-enabled warfare is beyond the scope of the role and responsibilities traditionally filled by J6 staff, and by the very nature of the cyber domain, involves all branches of headquarters staff.

- Creation of a Director-General Cyberspace Warfare and Integration within the Command Group of HQJOC,[32] to command a Cyber Coordination Centre and lead cyberspace warfare across domains, staff branches and organisations. Figure 4 shows an indicative structure and primary cyber integration tasks.

Conclusion

For the Joint Force to succeed in future war, plans, operations, logistics, communications and intelligence staff at Headquarters Joint Operations Command and each Joint Task Force must work together to understand the spectrum of cyber terrain, and how best to protect vulnerabilities and exploit opportunities at each phase of the operation. Manoeuvre and effects in the cyber domain must be given the same level of attention as manoeuvre and effects on land, sea and air, and not relegated to a single staff branch or niche planning group at each level of the Joint Force.

Future warfare will be cyber-enabled warfare. The ADF’s solution to preparing for and fighting cyber-enabled conflict cannot be further atomisation and stove piping along domain-centric structures and staff processes. Instead, it should be the wholehearted integration of cyber-enabled conflict across all existing staff areas and processes within the Joint Force. Cyberspace operations, both offensive and defensive, must be synchronised with manoeuvre, information activities, logistics and all other effects. If the Joint Force fails to achieve this, it risks defeat in and through cyberspace despite any tactical successes in the physical domains. While the responsibility for executing cyber operations rests with the few, understanding cyberspace and planning what to defend, disrupt and attack is a responsibility that must be shared by all.

Australian Cyber Security Centre, ‘About the ACSC’, Australian Signals Directorate (2020), https://www.cyber.gov.au/

Australian Cyber Security Centre, Australian Government Information Security Manual, Australian Signals Directorate (August 2020) accessed, https://www.cyber.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-08/Australian%20Government%20Information%20Security%20Manual%20%28August%202020%29.pdf

Australian Cyber Security Centre, ‘Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents’ Australian Signals Directorate (2020) accessed, https://www.cyber.gov.au/acsc/view-all-content/publications/strategies-mitigate-cyber-security-incidents

Australian Signals Directorate, ‘About ASD’, Australian Government (2020) accessed, https://www.asd.gov.au/about

Australian Signals Directorate, ‘Cyber Security’, Australian Government (2020) accessed, https://www.asd.gov.au/cyber

Australian Signals Directorate, The Commonwealth Cyber Security Posture in 2019: Report to Parliament March 2020, Australian Government (2020), accessed https://www.cyber.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-04/Commonwealth-Cyber-Security-Posture-2019.pdf

Braue, David. ‘Defence Consolidates cyber capabilities’, Information Age (13 August 2020) accessed https://ia.acs.org.au/article/2020/defence-consolidates-cyber-capabilities.html

Box, George and Norman Draper, Empirical Model-Building and Response Surfaces, (New York: Wiley, 1987)

Chief Information Officer Group, ‘What we do’, Department of Defence (2020), https://www.defence.gov.au/CIOG/WhatWeDo.asp

Department of Defence, ADDP 3.13 Information Activities Ed. 3, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australian (2013)

Accessed , https://www.defence.gov.au/FOI/Docs/Disclosures/330_1314_Document.pdf

Department of Defence, ADFP 5.0.1 Joint Military Appreciation Process Ed 2 AL3. (Commonwealth of Australia: 2019), accessed https://theforge.defence.gov.au/sites/default/files/adfp_5.0.1_joint_military_appreciation_process_ed2_al3_1.pdf

Department of Home Affairs, Australia’s Cyber Security Strategy 2020, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, (2020), accessed https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/cyber-security-subsite/files/cyber-security-strategy-2020.pdf

Farwell, James, and Rafal Rohozinski. ‘Stuxnet and the future of cyber war’, Survival 53, no. 1 (2011): 23-40.

Langner, Ralph. ‘Stuxnet: Dissecting a cyberwarfare weapon’, IEEE Security & Privacy 9, no. 3 (2011): 49-51

Metro, ‘Wars will move online, says head of UK’s armed forces,’ (09 Jan 2011), accessed https://metro.co.uk/2011/01/09/wars-will-move-online-says-head-of-armed-forces-gen-sir-david-richards-624268/

Morgan, Edward and Marcus Thompson, Building Allied Interoperability in the Indo-Pacific Region: Discussion Paper 3 Information Warfare: An Emergent Australian Defence Force Capability, (Washington DC: CSIS, 2018), accessed via https://www.csis.org/analysis/information-warfare-emergent-australian-defenceforce-capability

Ormrod, David and Benjamin Turnbull, ‘The cyber conceptual framework for developing military doctrine’, Defence Studies vol 16 no 3 (2016)

Schou, Corey, and Steven Hernandez, Information Assurance Handbook : Effective Computer Security and Risk Management Strategies, New York: McGraw-Hill Education (2015).

Wardrop, Christopher, ‘Bridging the gap between cyber strategy and operations: A missing layer of policy’, Australian Defence Force Journal, no. 204 (2018), accessed https://www.defence.gov.au/ADC/ADFJ/Documents/issue_204/ADFJournal204_Bridging_the_gap.pdf

US Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-12 Cyberspace Operations 08 June 2018, Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (2018), accessed https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_12.pdf

US National Initiative For Cybersecurity Careers and Study, ‘Cyber Operations and Planning course.’ (Arlington, VA: 2020) accessed, https://niccs.us-cert.gov/training/search/lunarline-inc/cyber-operations-and-planning

[1]Metro, ‘Wars will move online, says head of UK’s armed forces,’ (09 Jan 2011), accessed https://metro.co.uk/2011/01/09/wars-will-move-online-says-head-of-armed-forces-gen-sir-david-richards-624268/

[2] Ormrod, David and Benjamin Turnbull, ‘The cyber conceptual framework for developing military doctrine’, Defence Studies vol 16 no 3 (2016), p. 285

[3] ibid., p. 284

[4] Box, George and Norman Draper, Empirical Model-Building and Response Surfaces,

(New York: Wiley, 1987) p. 424

[5] Morgan, Edward and Marcus Thompson, Building Allied Interoperability in the Indo-Pacific Region: Discussion Paper 3 Information Warfare: An Emergent Australian Defence Force Capability, (Washington DC: CSIS, 2018), accessed via https://www.csis.org/analysis/information-warfare-emergent-australian-defenceforce-capability , p. 5

[6] Wardrop, Christopher, ‘Bridging the gap between cyber strategy and operations: A

missing layer of policy’, Australian Defence Force Journal, no. 204 (2018), p. 64

[7] ibid., p. 64-65

[8] The most obvious historic example of an attack through the cyber domain on a stand-alone industrial control system remains the use of STUXNET against uranium enrichment centrifuges at Natanz, Iran in 2010. For one of many analyses of this cyber-attack see: Langner, Ralph. ‘Stuxnet: Dissecting a cyberwarfare weapon.’ IEEE Security & Privacy 9, no. 3 (2011): 49-51.

[9] This essay will examine the application of US joint cyber doctrine, as Australian joint cyber doctrine is not publicly available.

[10] US Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-12 Cyberspace Operations 08 June 2018, Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (2018), accessed https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_12.pdf, pp. I-4 – I-5

[11] Defined as: ‘The coordinated, synchronised and appropriate use of communication activities and information capabilities in support of Defence’s policies, operations and activities in order to achieve the Department’s aims aligned with national goals. This includes Military Support to Public Diplomacy, Public Affairs and Information Activities where appropriate.’

Department of Defence, ADDP 3.13 Information Activities Ed. 3, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australian (2013)

Accessed , https://www.defence.gov.au/FOI/Docs/Disclosures/330_1314_Document.pdf, p. 48

[12] Department of Home Affairs, Australia’s Cyber Security Strategy 2020, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, (2020), accessed https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/cyber-security-subsite/files/cyber-security-strategy-2020.pdf, p. 18

[13]Australian Cyber Security Centre, ‘About the ACSC’, Australian Signals Directorate (2020), https://www.cyber.gov.au/

[14] Chief Information Officer Group, ‘What we do’, Department of Defence (2020), https://www.defence.gov.au/CIOG/WhatWeDo.asp

[15] Defined as: ‘actions taken within protected cyberspace to defeat specific threats that have breached or are threatening to breach cyberspace security measures and include actions to detect, characterize, counter, and mitigate threats, including malware or the unauthorized activities of users, and to restore the system to a secure configuration. cyber security.’

US Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-12 Cyberspace Operations 08 June 2018, p. GL-4

[16] Defined as: ‘missions to preserve the ability to utilize blue cyberspace capabilities and protect data, networks, cyberspace-enabled devices, and other designated systems by defeating on-going or imminent malicious cyberspace activity.’

US Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-12 Cyberspace Operations 08 June 2018, p. GL-4

[17] Australian Signals Directorate, ‘Cyber Security’, Australian Government (2020) accessed, https://www.asd.gov.au/cyber

[18] Australian Signals Directorate, The Commonwealth Cyber Security Posture in 2019: Report to Parliament March 2020, Australian Government (2020), accessed https://www.cyber.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-04/Commonwealth-Cyber-Security-Posture-2019.pdf, p. 3

[19] ‘The logical network layer consists of those elements of the network related to one another in a way that is abstracted from the physical network, based on the logic programming (code) that drives network components (i.e., the relationships are not necessarily tied to a specific physical link or node, but to their ability to be addressed logically and exchange or process data).’

US Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-12 Cyberspace Operations 08 June 2018, pp. I-3 – I-4

[20] US Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-12 Cyberspace Operations 08 June 2018, p. IV-5

[21] Defensive Cyberspace Operations-Response Actions ‘are the form of DCO mission where actions are taken external to the defended network or portion of cyberspace without the permission of the owner of the affected system. DCO-RA actions are normally in foreign cyberspace. Some DCO-RA missions may include actions that rise to the level of use of force, with physical damage or destruction of enemy systems, depending on broader operational context, such as the existence or imminence of open hostilities, the degree of certainty in attribution of the threat, the damage the threat has caused or is expected to cause, and national policy considerations. DCO-RA missions require a properly coordinated military order and careful consideration of scope, rules of engagement (ROE), and measurable objectives.’

US Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-12 Cyberspace Operations 08 June 2018, p. 3-12

[22] Australian Signals Directorate, ‘About ASD’, Australian Government (2020) accessed, https://www.asd.gov.au/about

[23] US Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-12 Cyberspace Operations 08 June 2018, p. I-5

[24] ibid., p. IV-5

[25] Ibid., p. IV-8

[26] ‘Cyberspace exploitation actions include military intelligence activities, maneuver, information collection, and other enabling actions required to prepare for future military operations.’

US Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-12 Cyberspace Operations 08 June 2018, p. II-6

[27] ‘Cyberspace attack actions create noticeable denial effects (i.e., degradation, disruption, or destruction) in cyberspace or manipulation that leads to denial effects in the physical domains. Unlike cyberspace exploitation actions, which are often intended to remain clandestine to be effective, cyberspace attack actions will be apparent to system operators or users, either immediately or eventually, since they remove some user functionality.’

US Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-12 Cyberspace Operations 08 June 2018, p. II-7

[28] ibid., p. GL-4

[29] Australian Cyber Security Centre, ‘Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents’ Australian Signals Directorate (2020) accessed, https://www.cyber.gov.au/acsc/view-all-content/publications/strategies-mitigate-cyber-security-incidents

[30] Braue, David. ‘Defence Consolidates cyber capabilities.’, Information Age (13 August 2020) accessed https://ia.acs.org.au/article/2020/defence-consolidates-cyber-capabilities.html

[31] Based on the curriculum and learning outcomes of the US National Initiative For Cybersecurity Careers and Study, ‘Cyber Operations and Planning course.’ (Arlington, VA: 2020) accessed, https://niccs.us-cert.gov/training/search/lunarline-inc/cyber-operations-and-planning or similar course.

[32] This position could potentially be dual-assigned within Defence SIGINT and Cyber Command, with a command relationship over Joint Cyber Unit for the prioritisation of tasks and force assignment and the access to build stronger relationships with ASD and ACSC.

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.