Defence in Australia has no military strategy for applying Australian military power for the achievement of government objectives. Australia’s inability to establish a military strategy tradition may be a consequence of the way the Defence structure and roles have morphed over the past half-century. Once it was capable of both defence and military strategy. Now, it is focused on just one: defence strategy for long-term capability generation. This shift can be traced through the consequences of three significant reviews, from the formation of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) resulting from the 1973 Tange Report, to the 1997 Defence Efficiency Review (DER) which confused defence and military strategy, and then the 2005 Wilson Review that recommended restructuring ADF higher command and control arrangements. This article will trace the history of organisational changes within Defence—the combined Department of Defence and ADF—that have resulted in an enterprise once capable of both defence and military strategy to one now focused on defence strategy.

The 1973 Tange Report

When the Report on the Reorganisation of the Defence Group of Departments was delivered in 1973, the Australian instrument for military strategic command was the Chiefs of Staff Committee (COSC) which had a full-time four-star Chairman (CCOSC).[1] The Chairman was the ‘government’s principal military adviser and was directly responsible to the Defence Minister’.[2] The COSC coordinated military activities of the Defence Force through the individual service Chiefs of Staff who also had their own Service Boards. Overseas operations were planned and managed by the individual services through their own operations and plans staffs.[3] The CCOSC had limited staff but was supported by a two-star Director Joint Staff who oversaw one-star Directors for Joint Policy and Operations & Plans. In parallel, the Secretary of the Department of Defence had a large staff that included a Level 3 First Assistant Secretary (FAS) Defence Planning who was responsible for strategic policy and defence planning.[4] The organisation was judged inefficient and more effective control was deemed required for military operations and activities.

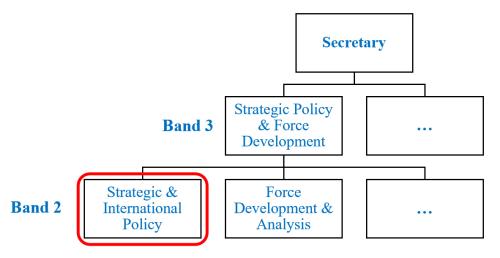

Tange recommended the individual service departments be combined into a single Department of Defence, the Service Boards be abolished and the creation of the Chief of The Defence Force Staff (CDFS) as a statutory authority.[5], [6] Of significance to this article, the report recommended the creation of a departmental organisation responsible for Defence planning which was concerned with strategic policy, force development and the conduct of international defence relations.[7] The new Deputy Secretary (DEPSEC) Strategic Policy and Force Development would be responsible for ‘Australia’s international Defence relations and strategic policy; analysis and recommendation of force structures and associated major weapons and equipment requirements; development of industrial capacity in support of Defence objectives.’[8] Figure 1 depicts the department structure relating to strategy, indicative of the period 1976-84. In essence, the function of this group was to deliver defence strategy—an enterprise-wide approach to creating military power in the long-term.

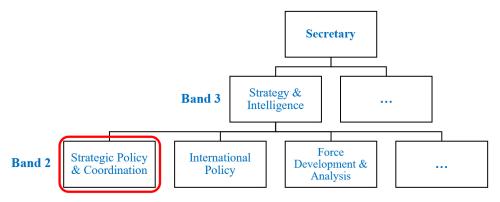

From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, there were minor name changes and reallocations of divisional responsibilities on the department side of Defence, but there was still a DEPSEC responsible for ‘defence strategy’ matters. An indicative structure of this period is shown in Figure 2.

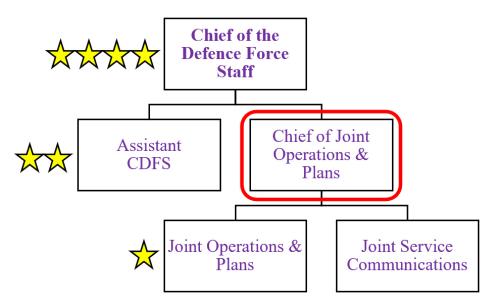

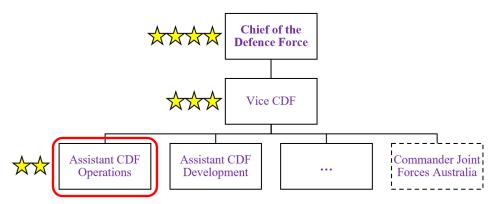

In the new ADF (which was officially established on 9 February 1976) and in direct support of the CDFS was a Chief of Joint Operations and Plans, responsible for Joint policy (the reconciliation of military objectives with other national policies[9]; what can be defined as military strategy), plans and operations. This is depicted in Figure 3. It should be remembered during this period and through to the early 1990s there were limited military operations requiring planning and coordination. Relatively minor changes were affected through the 1980s and early 1990s to provide the CDF (the title from October 1984) greater ability to command the ADF. In 1984, the CDF (General Sir Phillip Bennett) took the opportunity to reform his staff into two divisions, each headed by a two-staff Assistant CDF. The first was a Policy Division responsible for military strategic policy and inputs into force development. The second was an Operations Division that looked after joint operations and plans, logistics and joint exercise planning. In 1986, a Vice Chief of the Defence Force position was created as chief of staff of Headquarters ADF (HQADF) who was responsible for directing the two divisions.[10] Collectively, these two divisions provided the functions of military strategy—a theory for applying military power to achieve a government’s ends—and are depicted in Figure 4.

The 1997 Defence Efficiency Review

There have been more than 50 reviews of Defence since the Tange Review. Aside from relatively minor name changes and subordinate function realignments (including placing Defence intelligence functions under the DEPSEC and moving force development planning under the Assistant CDF Policy), these two organisations—one in the Department of Defence responsible for defence strategy and the other in HQADF responsible for military strategy—in substance largely remained the same until the Defence Efficiency Review (DER) in 1997. The DER precipitated the erosion of military strategy in Defence. This review, undertaken by a mix of military, bureaucrats and ‘CEOs of major private concerns’,[11] sought to ‘make recommendations for reforming Defence management and financial processes to ensure that they: are carried out in the most efficient and effective manner possible; [and] eliminate duplication between and within Defence programs…’[12] The DER recommended numerous structural changes.

Among the many changes accepted by the Government in the DER was the complete reorganisation of HQADF and the Department of Defence to form an integrated Australian Defence Headquarters (ADHQ), including the reduction of each Service headquarters to 100 personnel each. Twenty per cent of senior ADF and public service positions were to be eliminated.[13] A major concern of the DER panel was the way ‘strategic policy and planning support is provided to the CDF and Secretary, which boils down to the respective roles of the DEPSEC S&I [Strategy & Intelligence] and the VCDF’.[14] The report noted ‘there are several areas where the staffs of DEPSEC S&I and VCDF are duplicatively structured. Strategic guidance and force structure are two of the most prominent’.[15] The differentiation between defence strategy and military strategy was not made.

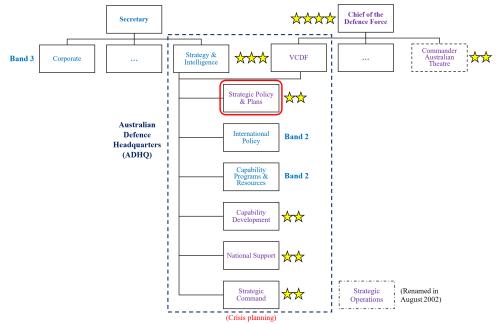

Within the integrated ADHQ, the report recommended DEPSEC S&I responsibilities included strategic policy and plans, long-term planning and preparedness policy, while VCDF responsibilities would include capability development and military plans. Both areas would have mixed civil and military staffs[16], including a two-star Head Strategic Policy & Plans working for DEPSEC S&I and a two-star Head Strategic Command under VCDF. This is shown in Figure 5. The DER noted this specific restructuring was ‘in the interests of efficiency’ and recommended ‘in the interests of effectiveness … a greater emphasis on producing longer-term strategic analyses’.[17] The Defence Science and Technology Group (DSTG) assessed, as a result of the DER, ‘VCDF’s responsibilities were blurred as the joint head of ADHQ [with DEPSEC S&I] and were limited, without formal control over any enabling programs’.[18] The DSTG paper noted operational experience since 1999 has confirmed the requirement for a Joint three-star officer at the strategic level to ‘assist the strategic command of operations’ supported by military staff; however, for peacetime functions the integrated nature of Defence at the strategic level necessitates these officers to contribute effectively to the integrated civilian-military enabling groups.[19] Finally, the DSTG paper states since the 1997 DER, ‘longer term military strategic planning has been integrated with Defence strategic policy, while limited planning for operations is conducted at the strategic level’.[20] Thus, the 1997 DER was the point at which the ability of Defence to undertake military strategy began to erode. However, the ADHQ experiment only lasted until 2000 and was changed (after more reviews) due to Government’s dissatisfaction with Defence acquisitions.[21]

The 2005 Wilson Review to now

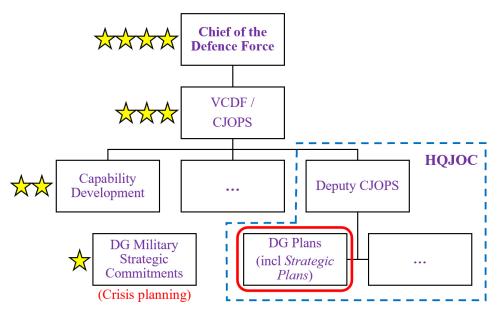

The erosion of the ability of Defence to undertake military strategy continued in the 2000s. The next major organisational review in Defence was the 2005 Report on the Review of Australian Defence Force Higher Command and Control Arrangements, the Wilson Review. After the surge in relatively substantial operations in East Timor, Iraq, Afghanistan and Solomon Islands, this review recommended establishing Headquarters Joint Operations Command (HQJOC) under the command of the VCDF to make command and control of ADF at the strategic and higher operational levels more effective.[22], [23] It is key to note command of HQJOC was initially retained at the strategic level.

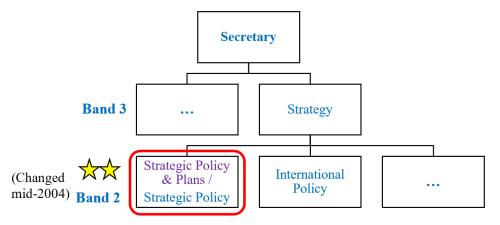

The Wilson Review also sought efficiencies and brought together in HQJOC planning elements from the strategic and operational levels (including Strategic Operations Division (SOD)—what Strategic Command Division was renamed in 2002) to achieve synergy, noting the VCDF straddled both the strategic and operational levels[24].[25] At this time, HQJOC included a dedicated Strategic Plans Directorate responsible for writing CDF’s orders and planning at the strategic level, with Head Strategic Policy and FAS International Policy accountable for strategic level plans.[26] The first iteration of HQJOC under VCDF is shown in Figure 6. Just before this period, in mid-2004, the position of Head Strategic Policy & Plans transitioned from a two-star ADF officer to the Senior Executive Service and was retitled FAS Strategic Policy. The department side of Defence at the same time is depicted in Figure 7.

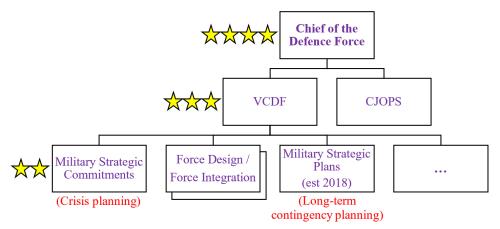

In 2007, and as a recommendation of the Defence Management Review, HQJOC was put under dedicated command of the Chief of Joint Operations (CJOPS) to ‘provide a more suitable balance between the management of Defence business at the strategic level and command of operations’.[27] This change of focus to the operational level did not result in the reallocation of strategic planning staff to the strategic level. The position of Head Military Strategic Commitments (HMSC) was reraised to a two-star (formerly HSOD) with a small staff to provide direct support to CDF and VCDF including ‘translating CDF intent and direction … into the appropriate products to enable the effective planning of operations, particularly in crisis (time critical) situations’.[28] By late-2007, no two-star officer was responsible for military strategy or deliberate (ie, non-crisis and non-contingency) strategic military planning.

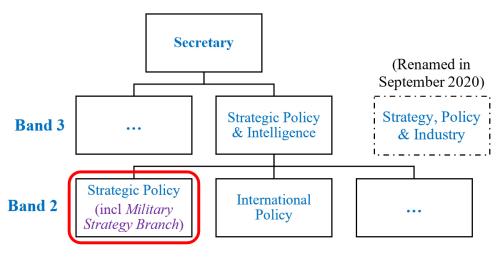

Two more efficiency-based enterprise initiatives were implemented after 2007: the Strategic Reform Program: Making it Happen in 2010 and theFirst Principles Review: Creating One Defence (FPR) in 2015. Both reviews focused on waste and efficiency, with the latter establishing the ‘Strategic Centre’, which includes ‘the Associate Secretary and VCDF [as the Deputy of the ADF] as the integrators for the Defence enterprise and the future force and joint capabilities respectively’.[29] Also, in the Strategic Centre was DEPSEC Strategic Policy and Intelligence (SP&I)[30], enhanced by a strong and credible internal contestability function, who is responsible for providing policy advice and intelligence assessments to the Secretary and CDF. The FPR recommended DEPSEC SP&I should ‘actively engage’ the VCDF in the ‘formulation of policy advice’ relating to the ADF.[31] At the strategic level, there remains a focus on defence strategy (ie, building future capability) despite relatively minor restructuring in 2019 and 2020 to establish the positions of Head Military Strategic Plans (HMSP) and Chief of Defence Intelligence (CDI) respectively.

The role of HMSP is restricted to ‘the development of long-range force-level military campaign planning’ focused on the ‘long-term geo-strategic environment’ for providing ‘future military options to Government’ and informing ‘the design and delivery of an advanced future force’.[32] The planning-horizon for HMSP is ahead of that of HMSC (usually crisis response and no more than 6-12 months) and CJOPS (out to five years): that is, greater than five years. The role does not include developing military strategy for employing the available force-in-being. Currently in the department side of Defence, FASSP is responsible for ensuring ‘strategy, capability and resources are aligned to Government priorities’.[33] Working to FASSP—and the remaining legacy from ADF Operations (and Plans) Division in the pre-DER era—is Military Strategy Branch. Despite its name, the branch is charged with ‘capability integration, strategic risk and futures, and wargaming and exercises’[34]; functions predominantly relating to defence strategy. The current Department and ADF structure relating to strategy are in Figures 8 and 9 respectively.

Conclusion

In 2022, Defence at the strategic level is focused on defence strategy under DEPSEC SP&I[35], and under VCDF is concentrated on long-term contingency planning, establishing new military commitments, overseeing existing operations and ADF activities, and crisis management. There is currently no focus on military strategy in Defence. Military strategy, however, will be essential to success in this period of strategic competition to align all instruments of national power behind a military campaign in competition or conflict. Defence will need to look at its strategic roles and responsibilities if it is to adopt the needed military strategy approach.

1 David M Horner, Strategic Command: General Sir John Wilton and Australia’s Asian Wars (Melbourne, VIC: Oxford University Press, 2005), xvii.

2 David M Horner, Strategic Command: General Sir John Wilton and Australia’s Asian Wars, 259.

3 Arthur H Tange (Secretary, Department of Defence), Report on the Reorganisation of the Defence Group of Departments (Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1973), 21, https://www.defence.gov.au/SPI/publications/1973reorg/AustralianDefenceForceReorganisation1973_opt_Part1.pdf.

4 Tange, Report on the Reorganisation of the Defence Group of Departments, Annex A.

5 Tange, Report on the Reorganisation of the Defence Group of Departments, 4-5.

6 It should be noted, General Sir John Wilton initially proposed the restructuring of the departments and the Defence Force when he was the CCOSC in 1967. David M Horner, ‘Chapter 10 The Higher Command Structure for Joint ADF Operations’ in History as Policy: Framing the Debate on the Future of Australia’s Defence Policy (Canberra, ACT: ANU Press, 2007), 148, accessed 8 April 2021.

7 Tange, Report on the Reorganisation of the Defence Group of Departments, 30.

8 Tange, Report on the Reorganisation of the Defence Group of Departments, Annex F.

9 Tange, Report on the Reorganisation of the Defence Group of Departments, 24.

10 David M Horner, Making the Australian Defence Force, The Australian Centenary History of Defence, Volume IV (South Melbourne, VIC: Oxford University Press, 2001), 62.

11 Eric Andrews, The Australian Centenary History of Defence, Volume V: The Department of Defence (Melbourne, VIC: Oxford University Press, 2001), 279.

12 Department of Defence, Future Directions for the Management of Australia's Defence: Report of the Defence Efficiency Review (Canberra, ACT: Department of Defence, Australian Government, 1997), 1.

13 David M Horner, Making the Australian Defence Force, 94-95.

14 Department of Defence, Report of the Defence Efficiency Review, 11.

15 Department of Defence, Report of the Defence Efficiency Review, 12.

16 Department of Defence, Report of the Defence Efficiency Review, 12.

17 Department of Defence, Report of the Defence Efficiency Review, 22.

18 Tim McKenna and Tim McKay, Australia’s Joint Approach (Fishermans Bend, VIC: Defence Science and Technology Group, Department of Defence, 2015), 4.

19 Tim McKenna and Tim McKay, Australia’s Joint Approach, 4.

20 Tim McKenna and Tim McKay, Australia’s Joint Approach, 36.

21 Eric Andrews, The Department of Defence, 288-299.

22 Richard G Wilson (Major General) (2005) Report on the Review of Australian Defence Force Higher Command and Control Arrangements (Canberra, ACT: Australian Defence Force, Australian Government, 2005), 5.

23 It should be noted, a restructure of the ADF for the command and control of Joint Forces on operations was a proposal dating back to CCOSC General Wilton in the 1960s; however, it was not until CDF General Bennett in 1987 that Joint Force arrangements were first formalised. David M Horner, Making the Australian Defence Force, 103-107.

The 1987Report of the Study into ADF Command Arrangements by Brigadier John Baker was seminal in defining the strategic, operational and tactical levels in ADF doctrine. A detailed study of the operational level is not needed for this paper.

24 The strategic level is concerned with the coordination and direction of national power to secure national objectives. The strategic level includes the national strategic and the military strategic levels. The military strategic level plans and directs military campaigns and operations to meet national strategic objectives. At the operational level, campaigns and operations are planned and conducted to achieve [military] strategic objectives. This level is primarily the responsibility of a theatre commander (usually CJOPS). The focus of command at the operational level is on forming joint forces, deploying them into areas of operations, monitoring and controlling operations, and sustaining them logistically. Australian Defence Force (ADF), ADF-P-0 Command and Control Ed 2 AL2 (Canberra, ACT: Defence Publishing Services, 2021), 38-39.

25 Wilson, Report on the Review of Australian Defence Force Higher Command and Control Arrangements, 5.

26 Wilson, Report on the Review of Australian Defence Force Higher Command and Control Arrangements, 32 and H-13.

27 Brendan Nelson (Minister for Defence), Defence Management Changes, Ministerial Media Release (archived), 19 September 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20080730091651/http:/www.minister.defence.gov.au/NelsonMintpl.cfm?CurrentId=7078.

28 Wilson, Report on the Review of Australian Defence Force Higher Command and Control Arrangements, 70.

29 Department of Defence, First Principles Review: Creating One Defence (Canberra, ACT: Department of Defence, Australian Government, 2015), 23.

30 Retitled DEPSEC Strategy, Policy & Industry on 1 September 2020 and also shortened to DEPSEC SP&I.

31 Department of Defence, First Principles Review: Creating One Defence, 26.

32 Department of Defence, Strengthening Military Strategic Planning, Joint Directive 10/2018 by the Chief of the Defence Force and Secretary (Canberra, ACT: Department of Defence, Australian Government, 2018), 1-2.

33 Celia Perkins (FASSP), Organisational Changes: Strategic Policy Division, DEFGRAM No 161/2021 (Canberra, ACT: Department of Defence, Australian Government, 19 April 2021), 2.

34 Celia Perkins, Organisational Changes: Strategic Policy Division, 3.

35 Retitled DEPSEC Strategy, Policy & Industry from DEPSEC Strategic Policy & Intelligence on 1 September 2020. The position of Chief of Defence Intelligence (CDI)—to include the role of Strategic J2—was established in September 2020 to command the new Defence Intelligence Group, which was formed from the intelligence agencies and functions of SP&I Group.

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.