‘It remains key for learning professionals to hold a valid insight into Microlearning and/or Microcredentials and their applicability within the Defence Learning Environment. Knowing their values, differences and relevance is vital—lest they become simply buzz words in learning.’

Introduction

The term ‘microcredential’[1] has grown in prominence globally over the last decade as an alternative to more established methods of achieving qualifications. Often associated with e-learning formats, its popularity recently rose in response to COVID restrictions and, as a concept, has been generally well received for its potential benefits for individuals, industries and educational providers.

While the concept has been readily employed within and across organisations associated with learning[2], its application may reflect differing intent and requirements. In order to standardise a common approach, national bodies[3] have sought to define a working framework to support efficient skills and knowledge development. Due to the relative infancy of such frameworks, an inconsistent understanding of the term microcredential appears to exist that may contribute towards inefficient or ineffective conduct, management or requirement of learning within organisations, Defence included.

Aim

The intent of this article is to demonstrate what the value of microcredentials may be within the Defence Learning Environment.

Scope

This aim will be met by defining the intent, content, benefits, requirements and criticisms or associated issues of microcredentials. This will be done through reference to a limited number of relevant academic reviews and local frameworks/models which will be compared to potential requirements of the ADF.

What is a microcredential?

While its definition may differ across organisations, in regards to its application the overall intent of microcredentials is relatively similar. Broadly, a microcredential is something that provides recognition against a discrete (small) body of completed learning. These discrete bodies of learning have been described as ‘chunks’ (Zhang & West, p 310); ‘tiny bursts’ (Jomah, et al, p 103); and ‘short learning experiences’ (Flynn, et al, p 3); amongst others. The term is further considered to reflect both the credentialing of learning as well as the learning activity itself.

Microcredentials may target (or contribute towards) a specific skill requirement of an industry (eg digital skills—Deakin University online short courses); a professional development requirement for an industry (eg Strategies to support working memory—Acree, p 3); or may reflect a higher education subset of knowledge/skill (eg Aeronautical Engineering Fundamentals—Register of NZQA-approved Micro-credentials). Through these learning chunks, skills and knowledge may be built upon (‘stacked’) to complement other chunks and potentially contribute towards a larger qualification (Wheelahan & Moodie, p 213).

Due to their accessibility (predominantly online), length and alignment with industry requirements, microcredentials can be desirable, as they reflect self-directed learning, are job-related, competency-based approached and based upon researched requirements (Acree, p 2). Through their ability to support self-directed learning, microcredentials enable individuals to own their learning and shape it towards an outcome that will benefit them as well as their desired industry (Jomah, et al, p 103). Conceptually, microcredentials provide a practical opportunity for learning that is delivered at a point of need and is flexible and efficient for the learner and organisation. This is intended to support more demographics to gain access to learning as well as ‘meet the future needs of work’ (Wheelahan & Moodie, p 222).

Content and development of a microcredential

The National Microcredentials Framework’s (NMF) definition of a microcredential (DESE, p 3) specifies that the learning activity is to contain a ‘minimum volume of learning of one hour’, and while it may be ‘additional’ to, an ‘alternate’ to, ‘complementary to or a component part of’, it is to be less than an awarded qualification under the Australian Qualification Framework[4] (AQF). The microcredential also certifies that the learning has been assessed. This requirement is echoed elsewhere so as to demonstrate ‘completion and mastery’ (Varadarajan, et al, p 9) as well as ‘… be measurable … and containing clear information on learning outcomes …’ (Flynn, et al, p 5).

In order to achieve the NMF’s definition of a microcredential, any associated learning should contain critical information (eg clearly stated learning outcomes), be transparent (ie able to be assured), be linked to an assessment strategy and be cognisant of AQF alignment[5] (DESE, pp16-19). Recognising these requirements, any organisation producing and/or delivering microcredentials should ensure the integrity of the learning and structure it as part of a defined and coherent pathway (Varadarajan et al, p 13).

In addition to an effective design-principled approach to the development of microcredentials, the learning should be certifiable and appropriately recorded. Facilitation of this may be achieved through the employment of a Learning Management System (LMS), or similar HR recording platform[6]; as much of microcredentialing is linked to online delivery, recording may be efficiently managed. This management may also enable the facilitation of results to be shared between organisations (Wheelahan & Moodie, p 214). Through this the microcredential may demonstrate a credibility of delivered outcome as well as an authenticity in its management.

Associated terms

Microcredentials are a relatively recent approach to the way in which learning may be managed and certified. While the formalisation of a national framework may be very recent[7], microcredentials were linked, in 2013, to learning provided through massive open online courses (MOOCs) (Ahmat et al, p 282). While titled as such, the microcredential was largely limited to its application with its host provider. Without a consistent product and supporting definition (ie framework) or pathway, microcredentials may have been (and were) subject to differing interpretations and applications. Other purposes, definitions and synonyms used in place of microcredentials for MOOCs included ‘microMasters’, ‘nanodegrees’ and ‘specialisations’ (Flynn, et al, p 3). While the outcomes of these learning activities were valuable to the associated industries, their credibility outside of them may have been questionable.

Digital badges.

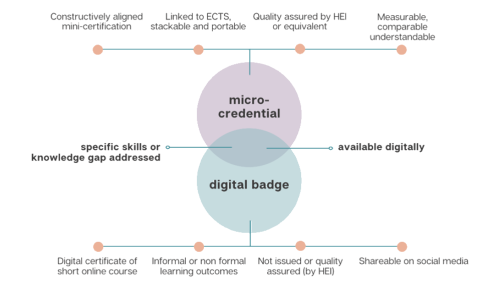

Further additional terms are also commonly linked to microcredentials, either as alternate definitions or as assumed equivalents. One of the most notable of these terms is ‘digital badges’ (Flynn, et al, p 3). Digital badges are logically tied to online learning, and through its contained metadata can provide a level of authenticity and transparency in regards to the conducted and completed learning (Flynn et al, p 4). Flynn et al (p 6) asserts that microcredentials hold associated but different purposes. Whereas a microcredential reflects an endorsed and conducted learning activity, digital badges may support learning that is more informal. While digital badges may reflect the achievement of a microcredential outcome in a digital format, such demonstration is, or can be, used to highlight the learner’s professional credibility online (inclusive of social media) and promote further learning (Denver University website). Figure 1 below demonstrates Flynn’s et al (p 6) outline of the relationship between microcredentials and digital badges.

Microclearning.

Microlearning is another term that may be associated with microcredentials. The key distinction between the terms is that microlearning is the learning activity whereas a microcredential signifies the accreditation of such learning in line with a formalised framework. Microlearning, as a result, has a level of flexibility to support other learning opportunities (non-formal learning) as well as provide the learning through means that may not require an assurance model, or one as detailed. Microlearning has the benefits to support even smaller chunks of learning (less than one hour) as well as providing a point-of-need refresher to learners (Zhang & West, pp 312-13).

Microlearning has been identified, however, as holding some limitations in comparison to microcredentials. Largely based upon its greater flexibility, microlearning may have less value in supporting complex skills, knowledge or behaviours; it may not provide confirmation of learning or provide feedback; and some learning activities may not be effective to satisfy the definition of learning (Jomah et al, p104).

Due to the potential for a less stringent/formal supporting framework, the associated learning design methodology permits greater accessibility and configuration for the learner to address individual requirements. Without the supporting framework this flexibility may, however, lead to an incoherent or inconsistent application by the individual/s so as to affect any benefit. By virtue of the flexibility of microlearning, it is, by itself, unable to meet the microcredential definition defined within the NMF.

Benefits of microcredentials

Rather than view microcredentials as the latest catchphrase or short-term trend, where appropriately modelled and employed they can provide value to organisations, industries and individuals. Under the more traditional approaches to learning, achievement of industry-relevant qualifications may be prohibitive (eg time or expense). Similarly, the industry or individual may consider only part of a qualification as necessary to meet their requirements. Under a microcredential framework, such skill sets do not need to be linked to a formal qualification and may be more easily achieved and employed, thereby permitting access to the workplace sooner (Ahmat, et al, p 286).

Microcredentials may also provide the benefit to recruitment or retention initiatives of an organisation or industry. As outlined by Acree (p 1), microcredentials can:

- Promote greater engagement with professional development

- Encourage skill practice within the workspace

- Support development of mastery.

For the individual, microcredentials may provide a more effective alternative in achieving a broader qualification. Where a microcredential is stacked with other microcredentials, a ‘macrocredential’ may be achieved. Such an approach may support an individual in gaining a qualification[8] where the microcredentials are mapped against a comprehensive pathway. Similarly, employment pathways may also be mapped across microcredentials in order to support skill requirements or shortages. Linked to a formalised framework and using authorised educational institutions/providers, such pathways can further support a broader industry rather than a specific employer (Varadarajan, et al, pp13-15).

Identifying the problems with applying microcredentials

Reflective of a comprehensive pathway program and employed under a formalised framework, microcredentials can provide benefit to organisations, industries and individuals. Conversely microcredentials may provide little to no value where supporting systems are non-existent, limited or poorly adhered to. From these considerations, a series of risks can be identified.

Conceptually, microcredentials are logical options to support specific skill development. If treated in isolation or incorrectly considered as a solution to all problems, microcredentials may be:

- Misunderstood by management/supervisors in their value or application

- Excessive to organisational requirements because formal accreditation/linkage with a qualification provides no ‘real’ value

- Purchased/employed in isolation without consideration of the broader pathway or currency requirements

- Narrow in focus and overly contextualised without consideration of the broader, or the organisation’s, application/requirements

- Conducted out of sequence or poorly paced, thereby undermining effective learning

- An administrative burden through record management requirements

- Assumed to be easily re-‘bundled’ by the learner as part of a stacked approach to conduct

- Confused with microlearning or digital badging outcomes

- Employed without consideration of alternatives or broader organisational application

- Subject to the learning provider’s criteria in regards to update requirements to maintain currency of credential without regard to the organisation’s needs.

Current application of microcredentials within Defence

Formally, microcredentials are employed in a limited manner within Defence as at writing, but appear to be growing in popularity. Three current Defence examples demonstrate different applications of microcredentials that show some of the identified advantages or problems.

Example 1

An organisation has cited engagement with an external learning provider to develop an e-learning product that will facilitate microcredentialing. In this instance, it appears that the concept of microcredentialing appears confused with digital badging and/or microlearning. This conclusion is arrived at because:

- The organisation’s definition of microcredentialing does not align with the NMF

- Learning activities may be shorter than 1 hour

- Learning outcomes are not necessarily linked to assessment

- Learning may be linked to refresher training

- Recording processes are unclear.

Example 2

An organisation hosts an online learning tool that cites ‘microcredentialing (informal or on the job proficiencies)’ as a benefit of its use. Like example 1, this instance appears to represent a misunderstood application of the tool and microcredentials. This conclusion is arrived at because the organisation’s application of microcredentials incorporates informal learning.

Example 3

An organisation advertises professional development providers. Among the listed courses and providers, one outlines microcredentials as an option for learning. This instance appears to be a generalisation and is unclear as to whether there is any value linked to the achievement of microcredentials (not the skill) as it may only reflect the considerations of a single provider (the MOOC provider only).

While all three examples seek to provide an alternative learning opportunity for the benefit of individuals and organisations, what they are providing and its value is uncertain.

Can microcredentials provide value to Defence?

The concept of providing learning that is flexible in delivery and accessibility, specific in nature, is presented in bite-sized chunks that are point-of-need focussed, and can be stacked with other activities, potentially provides versatility to how Defence delivers training and promotes learning. Current examples and historical precedents[9] indicate, however, that the value of microcredentials may be mixed.

Value may be realised where Defence either ‘unbundles’ qualifications (inclusive of UoCs) that currently exist[10] or engages with a provider that can facilitate this in accordance with the NMF. Such value, however, would be dependent upon its relevance to capability and provides a return on investment. Its employment should also be based upon sound design principles (ie the SADL) and considered for Defence writ large as opposed to isolated efforts.

Adoption of a common understanding of what a microcredential is, and is not, will further assist in the identification and development of suitable learning solutions for Defence. Through this, Defence may employ microcredentials, digital badging and microlearning more effectively. Where inconsistent application and employment of microcredentials occurs, Defence may see: an increase in administrative burdens; poorly advised individuals; problems with personnel and career management; confusing or conflicting learning pathways[11]; requirements for chasing currency of qualifications; an emphasis on qualification rather than the desired skill; or poor alignment with the overall qualification. The below tabled requirements may assist in understanding whether microcredentials would provide value to Defence.

| Requirement[12] | Essential?[13] | Microcredentials | Microlearning | Digital Badge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Outcomes are clearly stated | Yes | Required | Not required | Not required |

| Successful completion is ‘certified’ | Yes | Required | Not required | Required |

| Reflective of an AQF award qualification | No | Not required[14] | No | No |

| Developments consider AQF award qualifications | Yes | Required | No | No |

| Descriptions to consider ACSF | Yes | Required | Not required | Not required |

| Linked to an assessment strategy | Yes | Required | Not required | Not required |

| Minimum of 1 hour | Yes | Required | Not required | Not required |

| Duration/content to be less than an AQF qualification | Yes | Required | Required | Required |

| Clear associated assurance process | Yes | Required | Not required | Not required |

| Based upon a considered design process | Yes | Required | Not required | Not required |

| Supportive of industry recognition | Yes | Required | Not required | Not required |

| Linked to a Learning Outcome at minimum | Yes | Required | Not required | Not required |

| Interactive (not passive) | Yes | Required | Not required | Not required |

| Reliably recorded | Yes | Required | Not required | Required |

Table 1 – Comparison of requirements

Conclusion

As a learning option, microcredentials provide value where an associated pathway (organisational, professional, industry or regulated) is required. For Defence, such a pathway may be reflected in skill sets that complement multiple continua, support a gradual point-of-need delivery option or provide efficiency/effectiveness to capability. While microcredentials may provide value, they can require considerable investment in their development. Considerations should include the requirement for comprehensive pathways, their management, their conduct and coordination with other organisations.

Microcredentials will add another approach to learning that is subject to further management and administration for Defence’s learning environment. While potentially providing a level of flexibility, investment in them may prove excessive to actual requirements or returns. What is apparent, however, is that the value of microcredentials should be recognised as real as opposed to perceived prior to their application.

Biography

Paul Sylvester is a Major working within the Defence Education, Learning and Training Authority (DELTA) and is responsible for the maintenance and development of enterprise learning policy. Paul is a proud member of the Royal Australian Army Educational Corps and has been fortunate to have supported the conduct, management and development of learning across a number Army’s Training Centres and establishments. Notably of these, he has spent a total of 10 years involved in supporting ab initio learning, as part of the 1st Recruit Training Battalion and the Royal Military College – Duntroon. Paul holds a Masters in Adult Education, a Graduate Diploma in Secondary Education and an Arts Degree. Through his experience, qualifications and ongoing development, he strives to support the pragmatic application of learning solutions for the benefit of Defence.

Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) webpage, https://www.aqf.edu.au/, accessed 17 Apr 2023

DeakinCo. (University) website, What are Micro-credentials and how can they benefit both businesses and employees?, https://deakinco.com/resource/what-are-micro-credentials-and-how-can-they-benefit-both-businesses-and-employees/,

accessed 17 Apr 2023

Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE), National Microcredentials Framework, PWC, Nov 2021

New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) website – Micro-credentials, https://www.nzqa.govt.nz/providers-partners/approval-accreditation-and-registration/micro-credentials/, accessed 14 Apr 2023

University of Denver, Micro-credentials and Badges, Office of the Registrar website, https://www.du.edu/registrar/academic-programs/micro-credentials-badges#:~:text=A%20micro%2Dcredential%20is%20a,to%20showcase%20the%20earner%27s%20achievement, accessed 18 Apr 2023

Acree, L Seven Lessons Learned From Implementing Micro-credentials, The William & IDA Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, NC State University, 2016

Ahmat, NHC; Bashir, MAA; Razali, AR; Kasolang, S Micro-Credentials in Higher Education Institutions: Challenges and Opportunities, Asian Journal of University Education, Vol 17, No 3, Jul 2021

Flynn, S; Cullinane, E; Murphy, H; Wylie, N, Micro-credentials & Digital Badges: Definitions, Affordances and Design Considerations for Application in Higher Education Institutions, All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, Vol 15, No 1 (Spring 2023)

Jomah, O; Maoud, AK; Kishore, XP; Aurelia, S, Micro Learning: A Modernized Education System, Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience, Vol 7, Issue 1, Mar 2016

Varadarajan, S; Hwee Ling Koh, J; Daniel, BK, A systematic review of the opportunities and challenges of micro-credentials for multiple stakeholders: learners, employers, higher education institutions and government, International Journal of Education Technology in Higher Education, 20(1):13, Open Access, 2023, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, accessed 13 Apr 2023

Wheelahan, L; Moodie, G., Analysing micro-credentials in higher education: a Bernsteinian analysis, Journal of Curriculum Studies, 53:2, pp 212-228, DOI:10.1080/00220272.2021.1887358, 2021

Zhang, J; West, RE, Designing Microlearning Instruction for Professional Development Through a Competency Based Approach, Tech Trends 34, pp 310-318, Association for Education Communications & Technology, 2020

1 Microcredential is referred to here instead of micro-credential or micro credential in line with the National Microcredentials Framework (NMF)

2 Learning refers to the production, management, administration and delivery of learning related activities (e.g. training, instruction, education, etc.)

3 E.g. Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) NMF; NZAQs Approvals, accreditation and registration outline: Micro-credentials

4 The AQF awards reflect 10 levels of qualification ranging from VET certificate level education/training through to higher education doctoral degrees

5 Note - Microcredentials do not need to be aligned to an AQF award

6 Within Defence this might be achieved through PMKeyS

7 E.g. Australia and New Zealand 2022; Malaysia 2020

8 Inclusive of tertiary qualifications

9 Adherence to Defence owned UoCs was found burdensome in its management, administration and funding

10 Whether this is through the DRTO for accredited training or through the respective owner of that learner for unaccredited training

11 Where a single organisation provides a pathway without consideration of other organisations (Groups or Services)

12 As drawn from the NMF and Defence Enterprise Learning Policy (to be released at time of writing)

13 In accordance with meeting the NMF minimum standards of a microcredential

14 While not required, it can be because of the reliability of other associated requirements

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.