The rise of Robotics and Autonomous Systems (RAS) in all spheres of warfare has accelerated in recent times to a point where constant revision of tactics and procedures is now common practice[1]. The domain of Mine Warfare, and in particular Mine Counter Measures (MCM), is no exception. A heavy reliance on RAS has not only replaced proven tactics but has also placed a heavy reliance on the autonomous systems working efficiently, frequently at the cost of effective redundancy planning. This leads to the question: can we counter the autonomous systems in order to exploit the adversary’s decision-making process?

A natural byproduct of increased scrutiny on MCM has been the divergence of attention from purely mine clearance to offensive/defensive mining operations[2]. As RAS become the new normal in the context of MCM, one cannot help but seek to identify and exploit the known vulnerabilities of these autonomous systems for the purpose of increasing effectiveness of offensive mining efforts. The critical vulnerability of the MCM system, manned or otherwise, is the dependence of acoustic and magnetic search techniques as a means of location and identification of potential threats. This is in addition to the communications link vulnerability that plagues all unmanned technology and leaves it susceptible to electronic attack[3]. From an adversarial perspective, future opportunities to counter autonomous MCM operations exist through both kinetic and non-kinetic means.

Kinetic Attack

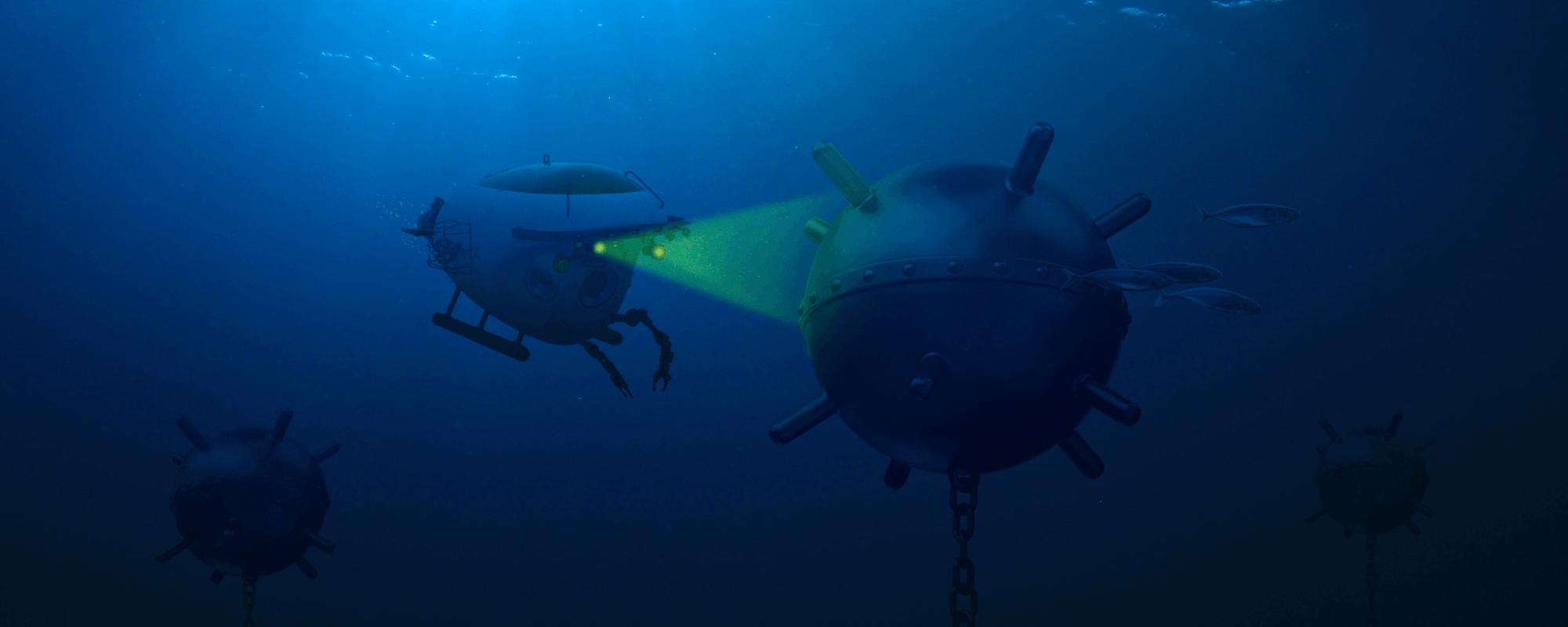

A simple model for countering autonomous assets is area denial of the minefield through kinetic attack tailored specifically for autonomous assets. This may take the form of underwater guided munitions, sowed amongst a real or distraction minefield, that specifically targets autonomous MCM assets. This could be achieved relatively simply and inexpensively, due to the small size of the munition required and the simplicity of a sensor package that actively seeks known operating frequency ranges of enemy autonomous search systems. The cost vs damage ratio would be favourable and the kinetic destruction of an autonomous asset by a counter measure does not confirm a minefield’s location, rather it leaves a sense of ambiguity of threat presence. The psychological effect of an autonomous asset being destroyed seconds after being sown into a possible minefield may also serve to quickly and efficiently enter the decision-making process of the enemy commander.

Argument could be made that a simple fishing net placed in the probable path of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUV) could delay the MCM effort. This is somewhat true; however, a lone kinetic counter measure could serve to provide the illusion of a persistent mine threat where there is none and degrade the adversary’s physical ability to conduct MCM operations through asset attrition at a favourable cost vs damage ratio. This concept is not restricted to underwater RAS, as Unmanned MCM Surface Vessels could also be targeted by these counter measures through search frequency identification and targeting.

Non-Kinetic Attack

Opportunities also exist for non-kinetic and clandestine countering of RAS behaviour models. Like any system that operates on a feedback loop (search/ return/ identify/ locate/ analysis/ action) there exists the opportunity to manipulate the flow of information overtly or clandestinely. One such opportunity would be the manipulation of information, namely the acoustic signature to delay, or prevent entirely, the positive identification and location of sea mines through acoustic jamming or acoustic signal manipulation.

This concept can be displayed through the provision of a hypothetical scenario.

The Blue force MCM UUV proceeds ahead of the main Amphibious Task Group (ATG), clearing a path through the contested waters surrounding Orange force-held littoral regions. The clearance route identified for UUV clearance will allow the Blue ATG to close to an optimal distance to launch amphibious forces to regain control of the islands. Intelligence suggests the sea approaches have been mined and the MCM forces have already located and neutralised a number of conventional sea mines. An unknown threat, a sea mine with the ability to subtly manipulate acoustic sonar returns from MCM RAS, waits in the approaches. The UUV proceeds along the clearance route, actively searching for anomalies that may indicate a possible mine, providing a visual representation of the acoustic return to the operator through a mission interface on the surface. The mine lays dormant until the acoustic signal from the UUV reaches it. A module within the mine identifies the frequency of the signal and triangulates the position of the UUV. Instantaneously the mine emits an acoustic signature that is received by the UUV’s receivers. This acoustic signal has been created by the sea mine, using the position and movement of the UUV, to alter the acoustic return of the UUV transponder, altering any possible return signal identifying an anomaly. The UUV continues receiving acoustic signals consistent with known sea bottom types, displaying a flat sea bottom with no contacts of interest, or a signal that represents a large submerged wreck that does not present a hazard to surface navigation, back to the operator. No anomalies are detected and the channel is assessed clear by the MCM forces. As the ATG moves through the channel, the sea mine functions, breaking the back of the high value target critical to Blue force success. A simple underwater weapon has not only managed to intercept and manipulate the information and behaviour cycles of enemy RAS, but has also managed to kinetically function as designed, proving the occupying forces with a relatively cheap mission kill.

Whilst this is somewhat beyond the scope of the function of current generation sea mines, the effect of manipulating sonar returns has been shown in nature. The tiger moth uses well-timed acoustic signals to evade predation by bats through jamming the bat’s echolocation method of hunting. Upon hearing the echolocation of the bat enter its terminal attack phase, the tiger moth emits a series of signals on the same frequency that is expected by the bat. The unexpected clicks emitted by the moth confuse (whilst not completely jamming) the echo location receptors of the bat by disrupting its known terminal location behaviour. This creates an error in the bat’s echolocation of the moth and affects the bat’s terminal attack phase. In controlled studies, the “silent” moths (not emitting the disruptive clicks) were 10 times more likely to be successfully caught by the bats than the moths emitting the acoustically disruptive clicks[4].

This behaviour displays the ability of the moths to use acoustics to successfully disrupt the echo location behaviour of the bats. In warfare, this could mean to intercept and disrupt the expected acoustic return and manipulate the information to disrupt the identification behaviour cycle of the RAS. Whilst current military examples of acoustic jamming exist, they are all overt countermeasures which completely block the acquisition of the desired acoustic return; none currently can manipulate the desired acoustic return and disruption of the identification behaviour cycle that is displayed by the tiger moth.

A consideration of this example of the tiger moth is that it displays an inherently overt method of acoustic manipulation not entirely appropriate for a clandestine weapon such as a sea mine. The overt manipulation of an acoustic signal would provide an exceptionally quick way of anomaly identification drawing unwanted attention to the mine. More importantly, this concept of information warfare through acoustic manipulation could be developed upon and introduced as a means for countering autonomous technologies and may significantly disrupt the mine warfare sphere if successfully developed.

Overall, significant opportunity exists for RAS to be countered in Mine Warfare, particularly in MCM operations. From an MCM standpoint, unmanned systems will reduce risk to human operators through provision of results from a distance, and may also serve to increase effectiveness of MCM operations through higher fidelity information. However, whilst these opportunities exist, so does the ability to subtly manipulate the technologies against the owner/user, or to even quickly remove the RAS asset from the battlefield altogether using a system with a favourable cost-to-damage ratio.

[1]Evans, A. William, Matthew Marge, Ethan Stump, Garrett Warnell, Joseph Conroy, Douglas Summers-Stay, and David Baran. "The future of human robot teams in the army: Factors affecting a model of human-system dialogue towards greater team collaboration." In Advances in Human Factors in Robots and Unmanned Systems, pp. 197-209. Springer, Cham, 2017.

[2]Doubleday, Justin. "Navy's expeditionary warfare office putting focus on offensive mining." Inside the Navy 29, no. 23 (2016): 1-5.

[3]https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/us-navy-quietly-starting-drone-revolution-naval-warfare-164683

[4]Fullard, JAMES H., JAMES A. Simmons, and PRESTOR A. Saillant. "Jamming bat echolocation: the dogbane tiger moth Cycnia tenera times its clicks to the terminal attack calls of the big brown bat Eptesicus fuscus." Journal of Experimental Biology 194, no. 1 (1994): 285-298.

Please let us know if you have discovered an issue with the content on this page.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.