The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the ADF, the Department of Defence or the Australian government.

What are the potential scenarios for a post-COVID global order and what effects may that have on Australian strategic policy?

Executive summary

Methodology. Alternative Futures Analysis was used to explore five scenarios with low probability but high impact upon Australia’s strategic environment and policy.

Common Themes. The scenarios identified two common threats; destabilisation of governments and degradation of the rules based international order. All scenarios identified changing values as the major source of threats and instability. This instability was amplified increasingly nationalistic governments and decreased international consensus.

Potential Opportunities. The scenarios identified a number of challenges which could present opportunities: resourcing, through gaining advantage from global fuel and trade instability; regional engagement, through influence and participation in global forums following great power instability; loss of global trade; and decline of international tourism.

Warnings and Indicators. Due to the immediacy of COVID-19, many of the indicators have already occurred. Potential warnings are evident for many medium-term implications including collapse of a super power and state isolationism.

Implications for Australian strategic policy.

Shape:

- Leader in the modernisation of international laws and conventions. Australia should take an active leadership role to obtain international consensus on critical issues such as the use of cyber, space and modified biological agents.

- Foster international balance and stability. In an increasingly unstable world, the essential role of international institutions remains and may in fact increase.

- Foster regional resilience and stability. Australia’s capacity for self-sufficiency means that it could become a net provider to regional nations.

Deter:

- Develop greater self-reliance in the absence of US support. Investment in military capability must continue to increase self-reliance.

- Develop international consensus on Antarctica. Australian strategic policy is weighted to the north and east. Militarisation of Antarctica by other nations could bring nations of the southern hemisphere under direct military threat.

Respond:

- Develop Australian energy supplies. Sustainable and self-sufficient methods of energy creation and fuel resources must be explored.

- Develop Australian industry, manufacturing and innovation. Self-sufficiency and sovereign production capability should exist for all critical resources.

- Identify novel threats and countermeasures. Australia should encourage experimentation in novel applications of existing or emerging technologies.

Introduction

The sudden emergence of the global viral pandemic known as ‘COVID-19’ has the potential to affect the global order in profound ways usually associated with the impacts of global warfare. The pandemic has directly affected the health of nations and international institutions and is likely to continue acting as an accelerator for pre-COVID-19 existing global trends whilst also providing opportunities for revisionist nations to reshape their domestic, regional or global environment. The unprecedented global disruption, complexity and uncertainty significantly broaden the possible range of outcomes.

This paper outlines a selection of scenarios in the post-COVID-19 world and their potential implications for Australian strategic policy. Those implications range from the immediate to the long-term and will require an integrated whole of government responses to ensure the sustained health and security of Australia as a nation among injured nations.

Methodology

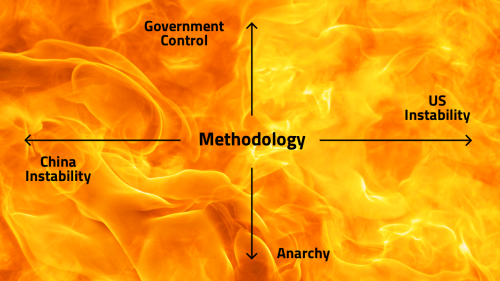

As a counterpoint to the thorough analysis of conventional scenarios already conducted by Defence, Team Sagan used Alternative Futures Analysis to explore a diverse range of scenarios with low probability but high impact upon Australia’s strategic environment domestically and internationally. Team Sagan structured the approach to the question of the shape and implications of the post-COVID-19 global order sought to manage the complexities implied by undertaking the following steps:

- Brainstorming. Individual and group brainstorming sessions on potential post-COVID-19 scenarios, to see if common assumptions or themes emerged.

- Assumptions. Alternative futures analysis generated the following assumptions about the likely effect of COVID-19 on individual nations and international norms. Those effects are anticipated to drive national behaviour in the post-COVID-19 global order:

- Financial weakness limiting investment in national power capabilities;

- Social fragility requiring increased domestic focus and driving a retreat from international systems that maintained the global order prior to COVID-19;

- Vulnerability of nations to opportunistic influence and coercion from external nations and organisations (including transnational crime, commercial predation);

- Diminished capacity to shape or respond to actions by other nations that threaten sovereignty of nations; and

- Susceptibility (reduced resilience) of individual citizens to destabilising misinformation (control and shape) campaigns mediated through social media. In Australia, this may affect trust in government and erode consensus for national strategic policy.

- Chart. Using common themes and trends that emerged, a two-axis chart to plot the broad sweep of the post-COVID-19 global order:

- On the horizontal axis: relative instability of China vs USA;

On the vertical axis: relative stability of institutional norms, government control vs anarchy.

- Scenarios. Informed by the assumptions and two-axis chart above, Team Sagan considered the pre-COVID-19 international context, including patterns of behaviours exhibited by specific nations, and refined five scenarios extrapolating pre-COVID-19 patterns into a future post-COVID-19 environment.

- Implications. While each scenario involves extreme geopolitical and socio-political developments in comparison with the pre-COVID-19 global order, Team Sagan analysed the set of scenarios to identify potential effects (and recommendations) for the future of Australian strategic policy.

Scenarios

Informed by the methodology above, Team Sagan developed the following scenarios through which to consider the shape of the post-COVID-19 global order and its potential effects on Australian strategic policy:

- Don’t leave Antarctica on ice. China will seek opportunities to influence amendments to the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) to permit unrestricted access to the abundant fishing and mineral resources of the region in order to meet domestic population growth pressures. China’s actions could evolve to include deployment of military capabilities intended to secure access to those resources. In this scenario, China’s Antarctic actions require Australian strategic policy to evolve, activating increased diplomatic efforts to shore up the ATS and expanding the traditional north-facing strategic defence focus to include a south-facing complement.

- Collapse of a super power. In an era of great power competition and contestation within the Indo-Pacific, what would the collapse of the globe’s largest power look like? This scenario will explore the impacts created by the effective breakdown of the United States of America in its ability to wield national power in an extrinsic fashion, as it has done since the end of the Second World War.

- Anarchy. Government collapses and the dissolution of social cohesion ensues following the rise of individualism and the creation of a Hobbesian mess. This scenario examines the disruption of social norms following the rise of the genetically immune who create an exclusive overclass within society, to the detriment of all others.

- COVID here to stay. Recurring bouts of COVID-19 have forced the rest of the world to accept the disease and accompanying mortality rate as a normal part of life. This scenario examines Australia’s role in the world as an island nation that has chosen to eliminate the disease. The greater weight on the value of human life comes at the cost of reduced global interaction.

- An ‘ethical’ option. This scenario explores the validity of the Biological Weapons Convention given scientific advances since the Convention came into force in 1975. Could a biological agent that is designed to incapacitate but not kill, and with negligible spread beyond the target population of combatants, be considered more ethical than kinetic warfare?

Common threats

The scenarios identified two primary threats as a result of COVID-19’s influence; destabilisation of governments and degradation of international norms. Both of these effects were driven by changing values and norms within societies.

Changing values

All of the scenarios identified changing values due to COVID-19 as being the major source of other threats and instabilities:

- Contrasting values. Although all major nations in the world are going to experience economic hardship as a result of COVID-19, contrasting values between nations will create greater relative decline in some nations over others dependent on where they place their economic priorities. Some nations, largely democratic, focus economic stimulus packages toward maintaining social structures and the humanitarian needs of their people, at the expense of national power. Other nations are likely to prioritise national power over the welfare of their people, resulting in a more efficient and targeted economic stimulus, assisting to maintain their relative economic might. This will result in stronger authoritarian states and weaker democratic states.

- Changing societal values. The COVID-19 pandemic has placed the social structure of many nations under pressure. Individuals are more likely to be focussed on their own needs over those of the society. States' priorities change as the social norms tend towards the rights of the individual to live a good life over the rights of others to live a long life. Nations may consider actions that were previously unacceptable in society to be required in order to maintain their position in the world. The role of stabilising international institutions decreases as nations look more inward to their own issues.

- Changing values impacting the alliance. The ‘collapse of the United States’ scenario specifically identified that the nature of the Australia and US alliance could change significantly. Cultural links to the United States created through Hollywood and the entertainment industry slowly decreased whilst the separation in foreign policy, health care and gun control policies increased exponentially. These opposing views between the nations relegated the alliance to one of convenience rather than one of shared values.

- Australian values. The ‘recurring COVID-19’ scenario identified that Australia’s international role is at risk of diminishing. If Australia’s values diverge from those of the rest of the globe in regards to preserving human life over preserving freedoms, it may increasingly set the nation apart and impact negatively on regional and global relationships.

Destabilised governments

The stability of governments in the scenarios was identified as a common threat which could have wider reaching impacts:

- Inward looking. Values turning towards the priority of the individual over the society impacts on domestic policies. This leads States to become more short term focussed and less stable in international politics due internal priorities and high turnover of governments.

- Social segregation. The impact (positive or negative) of COVID-19 on one population or ethnic group will drive resentment from and toward that group. Amplification of this resentment by state or non-state organisations may cause a potential social movement. Failure of government to adequately address the issue, may see that government ousted and a more radical system implemented.

- Domestic pressures. In the face of increasing population size and domestic resource pressures, along with increased isolationism, governments may turn to extreme measures to maintain power. Trust and cooperation between states may erode to the point that states may be emboldened to seize territory and resources if they cannot conduct normalised trade.

- Show of strength. Domestic dissatisfaction with the COVID-19 response may prompt some regimes to take action against long standing adversaries to bolster domestic cohesion and support.

- Anarchy. Breakdown of the social contract and cohesion may lead populations to reject official forms of government. Complete fragility would exist in all relationships be that political, military, economic, trade or any other sector. This would have flow on effects into all interstate relationships as well.

Degradation of international norms

The effect that changing values and destabilisation of governments would have on the international community would be devastating. The scenarios identified a number of common threats to the stability of international norms:

- Domestic pressures. With increased domestic financial and social pressure on governments around the world and a growing focus on internal issues, individual nations may elect to withdraw from existing agreements or refuse to ratify international conventions. This may be to maintain internal stability or to maximise benefits to their own nation in some cases. The trajectory of this process may be difficult to predict and could be subject to intense interstate pressures, both to conform and to undermine existing international norms.

- Globalisation. Reducing globalisation due to supply chain issues throughout COVID-19 takes the focus away from the importance of international norms for a time, this may allow states to shape these towards their own benefit. This becomes a greater issue decades down the track as the world tends back toward globalisation and realises the norms have changed.

- Competition for power. Reducing internal and international governance would naturally tend toward competition for power. The breakdown of the social contract and cohesion if extrapolated to Global levels would see a complete breakdown of recognised international systems. While current world organisations provide a framework from which deviation can be made to achieve common consensus, in a world void of a common framework, international relationships at all levels would fracture.

- Stagnation. International laws and norms have arguably already stagnated in comparison to the rapid development of science and technology. This stagnation may become increasingly pronounced due to COVID-19 impacts. States and non-state organisations are more likely to act outside existing conventions, potentially setting new precedents for international competition and conflict where international laws and norms do not meet contemporary needs.

- Decreasing international consensus. Decreasing international consensus on the militarised use of chemical weapons, biological agents and cyber may offer an attractive advantage that may not attract universal condemnation if used astutely. States may assess that unified international action is less likely due to decreasing globalisation and increasing nationalism, particularly if territorial gains are secured quickly and heavily defended.

Possible opportunities

The scenarios identified a number of challenges which could present opportunities if they are managed appropriately, particularly in the fields of resourcing and regional engagement.

Resourcing

Fuel instability. Instability in the world impacts negatively on fuel sources. Diminishing economies and internal resource management makes fuel exports less favourable and many governments seize control of fuel resources. Australia can enact the March 2020 agreement with the US to tap into emergency reserves, however, this was identified as only lasting for 12 months before the US was unwilling to continue its support for it. Putting emergency fuel reserves at risk. The Australian government were unable to financially support private citizens and industry due to the rising fuel costs. Defence fuel availability became unsustainable and prioritisation for capabilities became a debated topic. In response to the fuel crisis and as a way to increase available jobs and lower fuel prices, Australia invested in oil refineries and fuel reserves. Australia drove research and development into solar and nuclear energy production, reducing the impact of economic uncertainty to the average Australian.

Trade instability. Reduced globalisation and increasing restrictions on trade agreements as nations turn inwards to protect their own interests, will place pressure on Australia. Australia would need to head towards self-sufficiency. Raw materials and energy sources would be the greatest challenge. Greater investment into processing of raw materials in Australia and development of broader industry would serve the dual purpose of achieving material requirements as well as reducing unemployment. Leveraging the unemployed but technologically advanced youth of the nation could present useful national innovation and stabilise societal unrest. New forms of energy sources would need to be developed as technology improves. Reinvesting in international relationships that bolster availability to new technologies would work hand in hand with Australian sovereign innovation. International trade may need to be restricted to specific nations with high levels of supply chain security that are able to guarantee low risk goods. Australia can also leverage off its already high level of quarantine practices to assist other nations in supply chain sanitation.

Regional engagement

Great power instability. Global instability, and in particular US instability, leads to these nations withdrawing from the region and creating a power vacuum. Australia as a fairly stable nation with relatively less impact from COVID-19 begins investing more heavily in the region. Increased defence cooperation programs and multinational operations become the primary focus for defence-based diplomacy. Indonesia, with Australian medical and aid assistance, is able to recover quickly after COVID-19. Its acceleration in terms of economic growth is restarted, but its population growth overtakes its ability to resource the nation. Australia seizes this as an opportunity and provides humanitarian and defence force support in return for forward basing provisions in Indonesia.

Tourism. Lockdowns during the pandemic have a devastating effect on many tourism dependent nations in the local region. Tourism dependence on an Australian customer base for many of the Indo-Pacific nations is realised during the Pandemic, supporting more favourable diplomacy between Australia and the Archipelago island nations.

Energy. In order to support its own energy needs Australia invested in oil refineries, fuel reserves and alternate energies such as solar and nuclear energy. This reinforced Australian energy production capacity also allows energy support to neighbouring nations in the Archipelago, creating an energy provision dependence on Australia, stabilising jobs, fuel sources and society.

Industry and trade. Australia's investment into sovereign industry in order to overcome trade challenges and increase its self-reliance, provides a regional opportunity as well. Reduced globalisation and enhanced Australian local industry enables Australia to become a primary trading partner to its region. The ability to setup improved quarantining facilities may present an opportunity for Australia to provide a lower risk supply chain to the smaller nations in the immediate region.

Warning indicators

Immediate to near term

‘Ethical’ biological warfare. Arguably the permissive environment for this scenario already exists. International tolerance for the militarised use of chemical agents has gradually increased, with chemical agents designed to incapacitate rather than kill used in hostage situations (Dando 2009). The use of chemical weapons in the Syrian civil war was denounced by many nations, however, the lack of universal condemnation hindered effective deterrence or prevention (Notte 2020). Contention on the use of chemical weapons is indicative of the decreasing consensus on the use of nuclear energy, biological agents and cyber security. Unless the great powers display cooperative leadership in addressing these issues, states may take advantage of the uncertainty to exploit the ‘grey zone’ and establish precedents as to militarised use.

Medium term

Collapse of a super power. United States foreign policy immediately following the 2020 presidential election will provide an indicator to possible instability in the future. Potential warning signs include reduced troop and funding commitments to international organisations and withdrawal from existing international commitments in order to focus resources on managing domestic affairs. Additionally, the US may soften its interpretation of treaty obligations, requiring greater self-reliance from allies and reducing support expectations. US domestic policy and reporting may also indicate increasing instability through deepening polarisation of the population on political, racial and cultural grounds, rising social inequality, and the rapid growth of armed extremist and vigilante groups offering protection and a platform to promote self-interested policies. Key political leaders are likely to become either more authoritarian in an attempt to suppress rising anger and civil disobedience, or more permissive in an attempt to placate issue motivated groups. The descent into civil unrest may be accelerated by decreased funding and staffing of security agencies in response to the public losing faith in security institutions.

Anarchy. Likely warning signs include repeated failure to achieve a successful immunisation programme against COVID-19 (or mutations) combined with indicators of genetic immunity or genetic susceptibility amongst certain population groups. Additionally, extended and widespread implementation of lockdown situations, sufficiently protracted as to achieve significant behavioural change within the population. Inability to prevent transmission of pathogens via ‘non organic’ materials lead to stagnation of the global supply chain. These trends could exacerbate social inequality and grievances leading to civil unrest and conflict.

Isolationist Australia. Potential indicators include international forums like the UN not upholding current standards of Human Rights or modifying definitions of protecting populations from harm would indicate acceptance of lifted restrictions and thereby greater mortality rates. For example, Sweden’s approach of light restrictions initially received condemnation amongst other Western cultures, however, international opinion is already shifting towards alternate approaches to managing COVID-19 given community lockdowns have not succeeded in eliminating virus transmission.

Longer term

Militarisation of Antarctica. Likely indicators include increased attempts by China to influence other nations to weaken the Antarctic Treaty System and resistance to site inspections permitted by the Treaty System. Additionally, China (potentially supported by Russia) is likely to make a concerted effort to secure international consensus that Antarctic nations should be allowed the freedom to pursue their activities without interference. This could be complemented by increased activity to/from/within Chinese Antarctic facilities. Seismic activity within the vicinity of Chinese facilities may indicate subterranean construction of expanded facilities with the potential to host military hardware. The actions of other nations who are parties to the Antarctic Treaty System may indicate “alert” at Chinese (or other nations’) activities. The USA is a signatory party to the treaty; however, has not made any claim over any territory in Antarctica. Therefore, an increase in American interest in Antarctica could indicate a shift in the position of Antarctica within American strategic policy.

Implications for Australian strategic policy

The two main themes that are common among the scenarios are Australia being a regional leader and driver of international institutions and increasing national resilience. These themes can be communicated using the 2020 Defence Strategic Update strategic objectives of Shape, deter, and respond.

Shape

Leader in the modernisation of international laws and conventions. Decreased globalisation and increased nationalism means that states are less likely to participate in negotiations to review existing international laws and conventions. States will be unwilling to reveal capabilities under development or novel applications of existing capabilities, which would relinquish the element of surprise and enable countering tactics to be developed. States are likely to have less confidence in revised international laws and norms being enforced, particularly with the US no longer able to act as a global security guarantor. Instead, states may elect to form their own precedents if they perceive they have sufficient scope to argue that their approach is more appropriate than outdated conventions. Australia promotes a rules-based global order but must not assume that other states will adhere to its interpretation of international laws and norms. Instead, it must explore ways that scientific and technological advances could be used against it and identify potential countermeasures. Alternatively, Australia could choose to take an active leadership role to obtain international consensus on critical aspects of grey zone warfare, such as the use of modified biological agents.

Foster international balance and stability. Even if globalisation is in decline the essential role of international institutions remains and may in fact increase. In an increasingly unstable world with changing norms it is important for nations with strong commitment to international standards to ensure their voice is heard.

Foster regional resilience and stability. Australia’s reduced need for COVID-19 related medical supplies would provide an opportunity to assist vulnerable regional nations by manufacturing and supplying these items for them. Continuing to provide aid in the local region would be essential to ensuring these nearer nations do not fall prey to powerful nations trying to coerce them. The greater capacity Australia has for self-sufficiency may also mean it can become a provider to other local nations, reducing their reliance on the wider world and thereby assisting them to reduce infection rates. Australia could become a ‘regional trade hub’ by setting up a major import and export control hub in the North. Whilst unpopular the mines have already shown Australian’s are willing to live the fly in fly out life, this would assist unemployment and justify further national capacity build-up in terms of manufacturing. If globalisation is reducing, perhaps it is time for regionalisation to increase.

Deter

Develop greater self-reliance in the absence of US support. Military presence, capability (size and platforms) and logistics must continue to be invested in. Military diplomacy within the immediate region is key to increasing self-reliance and lessening the impact of a lack of support from ANZUS.

Develop international consensus on Antarctica and potential coalition force to protect against exploitation. Deployment by China of offensive (or potentially offensive) capabilities in Antarctica will require adjustments in Australian strategic policy. China’s military activities will increase the risks associated with any attempt by Australia to assert its claims in Antarctica. This will complicate Australia’s strategic policy options in the Antarctic region and will present wider concurrency issues. Currently, Australian strategic policy is weighted to the north and east – the region from which most threats to Australia are expected to emerge. Militarisation of Antarctica by China (or other nations, including Russia and to a lesser extent USA) will restrict freedom of activity in the Antarctic region, and could bring nations of the southern hemisphere under direct military threat. The militarisation of Antarctica would require a southward complement to Australia’s northern and eastern strategic focus.

Respond

Develop Australian generated energy supplies or alternate energy suppliers. More options for fuel resources must be explored. The March 2020 agreement with the US might not be viable, nor might it be sufficient for Australia’s requirements. Solar options as a sustainable and self-sufficient method of energy creation could also assist in ensuring critical infrastructure like hospitals remain certain.

Develop Australian industry, manufacturing and innovation. We are already seeing the early signs of this in defence procurement. However, self-sufficiency extends beyond the purchasing of military equipment and will also rely on food production internally to Australia as demonstrated during COVID-19 initial periods of restrictions.

Identify possible novel threats and potential countermeasures. Defence should encourage experimentation in novel uses of existing or emerging technologies through innovation seminars, wargaming or through existing science fiction writing competitions. Innovative thinking should be encouraged and rewarded, but clear guidelines should be provided to ensure ideas are explored in a safe and appropriate manner.

Conclusion

The future is uncertain. Of that we can be certain.

The shock and disruption of COVID-19 has been sharp and disorientating. The full effects of COVID-19 on the health of the global order will take many years to evolve. However, Australian strategic policy does not have the luxury of decades to determine a way forward that will ensure the health and security of Australia and its immediate region. Prior to COVID-19, regional population growth, economic growth and military modernisation were set to present significant challenges to Australian national power. Relatively, Australia had anticipated a decline. In the post-COVID-19 global order, Australia has an opportunity to exploit the weakness of other nations not exclusively for national gain but also to protect the values of international security and peace that have underpinned Australia’s prosperity.

Effective strategic policy can assist Australia to envisage and articulate how it will engage with the world for a more positive future. The future is uncertain; yes. [Perry-lous even… - excuse the Dad joke!] But a future in which Australia does not toil for a clear view of potential complexities and pathways forward is certain to be a future commanded by nations who may not have Australia’s best interests in mind.

Carl Sagan once remarked, “Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.” Australian strategic policy must strive to know, and through knowing open the door to bringing the future into being on Australian terms.

Annexes

A. Scenario: Don’t leave Antarctica on ice

B. Scenario: Collapse of a super power

D. Scenario: COVID here to stay – what if there’s no vaccine for COVID-19

E. Scenario: Means other than war: could biological weapons be an acceptable tool of war?

SCENARIO: DON’T LEAVE ANTARCTICA ON ICE

Post-COVID-19 context

Pre-COVID-19 behaviour: Continuing a pattern established prior to COVID-19, China will accelerate attempts to revise international systems where the trade-off between risks and rewards generates a net benefit for China’s long term national interests.

Drivers of future behaviour: China’s future national interests are likely to include increased domestic demand for resources to support the standard of living of a growing population. The domestic tensions associated with higher resource demands and expectations of improving living standards may push the Chinese government toward internationally competitive attempts to control and extract resources from Antarctica. Accordingly, the restrictions imposed by the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) will become increasingly onerous for the Chinese and will drive attempts to adjust the ATS.

Scenario: Chinese attempts to weaken the Antarctic Treaty System and/or Militarise Antarctica

Specific Arena of Contest, Antarctica: The various documents that comprise the ATS place stringent restrictions on military activity[1] and resource exploitation.[2] The year 2048 offers an opportunity for signatory parties to the ATS to review the operation of the ATS. This date is adjacent to the 2049 centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, which marks the date by which the Chinese Communist Party intends to have completed its program of modernisation and national rejuvenation. At that future date, China will expect to operate with sovereign independence in the Indo-Pacific region. The confluence of dates may encourage China to seek opportunities to facilitate adjustment of the ATS across the 20-30 year period preceding the Chinese centenary.

As domestic resourcing pressures grow, China may seek to secure Antarctic resources and deter/deny other nations’ attempts to access those resources. Cultivation of revisionist opportunities may be pursued through coercion and other influence operations targeting nations who are signatories to the ATS. Coercive actions will be intended to build support for, or discourage resistance to, China’s expanding presence[3] and future assertion of Antarctic territorial and resource claims.

Attempts to improve China’s position within the rules-based system protecting Antarctica would be strengthened through military activity. China may attempt overt or covert militarisation of its presence in Antarctica either after adjustments are made to the ATS to permit such actions, and/or in direct contravention of the ATS:

- Overt attempts to militarise Antarctica: the process of militarisation could be incremental, with each step falling below the threshold that would trigger a strong international response (Grey Zone increments). This process could lead to the evolution of habitations unambiguously declared as military establishments, including SIGINT facilities perhaps presented as part of a global network of bases ‘supporting’ the space-based BeiDou navigation satellite system.

- Covert attempts to militarise Antarctica: (#scifi warning) this might include construction of subterranean long-range ballistic missile batteries, positioned under the ice cap for thermal shielding. These installations could be constructed piece by piece, ensuring no large components are observable during transit to the construction site. Construction would require excavation, which may in turn require use of explosives. Such noisy terraforming activity would draw attention. China could employ seismic masking to conceal construction activities. Controlled explosives and other sonic means could create the seismographic illusion of earthquakes/icequakes to shield simultaneous explosions (or other physical activities) used in the process of excavating subterranean bases.

Implications for Australia’s strategic policy

The challenges of mounting an effective defence effort in support of Australia’s Antarctic claims has long been considered insurmountable.[4] Australia’s consistent policy has been to pursue maintenance of the existing ATS under which the Antarctic is not militarised and territorial claims are suspended.[5] Deployment by China of offensive (or potentially-offensive) capabilities in Antarctica would require adjustments in Australian strategic policy. China’s military activities will increase the risks associated with any attempt by Australia to maintain or assert its claims in Antarctica.[6] This will complicate Australia’s strategic policy options in the Antarctic region and will present wider concurrency issues.

Currently, Australian strategic policy is weighted to the north and east – the region from which most threats to Australia are expected to emerge. Militarisation of Antarctica by China (or other nations, including Russia and to a lesser extent USA) would restrict freedom of activity in the Antarctic region, and could bring nations of the southern hemisphere under direct military threat. The militarisation of Antarctica would require a southward complement to Australia’s northern and eastern strategic focus. These implications would call for expansion and refinement of activities across the Australian strategic policy community, including long-term planning in diplomatic activities, and enhancements generated by the integration and harmonisation of related policy programs across government.

Recommendations

The following recommendations may improve Australia’s ability to (1) develop effective strategic policy options to address Chinese activities in the Antarctic region, and (2) implement strategic policy in an efficient and effective manner communicable to the Australian audiences.

| Department | Strategic Policy | Activities |

| Whole of Government | Explicit policy harmonisation across departments. | Analysis of policies and programs external to Defence to understand the degree to which they have the potential to thwart achievement of Defence outcomes. Greater policy harmonisation may assist in reducing wastage and other negative impacts on the public (and could lead to improved public trust in government). |

| Department of Foreign affairs and Trade | Increased diplomatic engagement to strengthen international consensus for ATS status quo across the next 20-30 years. |

|

| Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment[7] (Australian Antarctic Division) | Increased scientific monitoring and treaty inspections in Antarctica. |

|

| Department of Defence | Increased investment in capabilities to shape, deter and respond in the Antarctic region and in Australia’s southern approaches. |

|

SCENARIO: THE COLLAPSE OF A SUPER POWER

“That was when they suspended the Constitution. They said it would be temporary. There wasn't even any rioting in the streets. People stayed home at night, watching television, looking for some direction. There wasn't even an enemy you could put your finger on.”[9]

– The Handmaid’s Tale.

Time now: 10 Jan 2030

Situation now

The United States is, according to definition, returning from being a failed state. It has published the Final Constitution, which, after 5 years of debating has not been accepted by the whole population. ‘True Americans’ believe the newly published document to be false and “un-American” in its messaging. Political science academics general assessment appears to agree that this new constitution is written with the same intent as the previous document, but has been brought into the modern era and uses more modern and specific language, interpreted as a threat to the “American Way of Life” by the ‘True American’ ideology. The concept of a ‘silent majority’ has well and truly gone.[10] Social and mainstream media coverage has led to subtle divides in American society, whereby it is expected for you to have picked a side, you are either a ‘True American’ or you are a ‘New American’ – there is no societal acceptance of indifference or abstaining. Current assessments of the political geography is that ‘New Americans’ make up 60% of the population, but there is no single geographical border or divide between the two groups.[11] Depending on the city or state the laydown of political sympathy can be split into sectors of cities with suburbs divided by ideological beliefs or groups can co-exist within the same localities with only minor disturbances of the peace. Police forces are almost completely aligned to one particular ideology as an organisation.[12] The former Department of Defence is in the process of being re-raised under the organisational title of ‘The United States Defence Force’. Functionally the goal is to rebuild a force similar to that of pre-COVID-19.

What happened

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States of America harder than other nations of its size. It will later be assessed that the biggest problem faced by states attempting to implement control measures was a prevailing perception, in some parts of society, that personal liberty was being impeded. Common understanding now is that the long-standing debate over gun control and reform created an already heightened tension with those who believed they were at risk of oppression.[13] Disease control measures such as the wearing of masks and social distancing were seen by some to be the final straw of government control.[14] That alone was one factor combined with the political turbulence surrounding the 2020 election and the distrust in the political legitimacy of elected leaders, through inflammatory use of social media. Social media created a platform for extremist views which became more accepted as parts of society became disillusioned with the state and federal governments.[15] The generally agreed flashpoint came in late 2020, when the incumbent President refused to accept the election results. This created an initial reaction of civil unrest in most major cities in the country.[16] That civil unrest did not remain peaceful and the police forces reacted. In some cases, the National Guard was deployed to conduct public order actions. The Joint Chiefs of Staff refused direction to intervene with military forces on the streets until a ratified government was established.[17] For the most part the civil unrest was short lived and the government began the process of establishing a new administration. The infection rate of COVID-19 cases accelerated to unmanageable levels. The already politically divided nation, began to sperate itself in more significant levels as the government struggled to manage the COVID-19 response.

Between 2021 and 2024 the United States went into decline as its global influence fell and its economy crashed. The economic situation in the United States was described as being worse that the Wall Street Crash. Extreme poverty, crime and homelessness rose to unprecedented levels. Deployed troops around the world were reduced to the lowest levels since before the Second World War. Presence in Japan was reduced significantly and became a rotational force and Marine Rotational Force – Darwin was collapsed all together.

In 2024 The leader of the New America Political Party led a successful bid for President, on a campaign of rebuilding the Nation from the ashes of a previously great nation. Constitutional reform was the major element of the campaign. Upon being sworn into office, the President relinquished their leadership role of the New America Party, but supported successful campaigns in the House of Representatives and the Senate. The New America Party gained a majority of both houses the same year.

As the New America Party began implementing its policies and bills, those loyal to the original constitution and those feeling marginalised by the severe political change began to rally in groups, growing in extremist views.

Some states began declaring themselves seceded from the Union.[18] Rural areas of Washington and Oregon claim to be established as stand-alone states. All states eventually return to majority acceptance of the Union.

2024 the COVID-19 vaccine was distributed world wide.

A short insurgency conflict took place between 2025-2026. The insurgency agreed to a ceasefire if provided with political legitimacy for its political representatives. Agreeing to this meant reform of the electoral college system, which was already an agenda item for the New America Party.

By 2030 the United States is rebuilding itself and has made significant progress in growing its economy and the standard of living for its population.

Impact to Australia

Defence policy. The 2020 Defence Update set the conditions for a first step in independence in terms of defence of Australia and national security. A re-emergence of the Defence of Australia strategic concept occurred. Defence development of early warning radar, forward intelligence assets and long-range strike capability became rushed and were underfunded.

Culture and values. Cultural links to the United States created through Hollywood and the entertainment industry continued to influence popular culture and views in Australia, but the saturation and levels of influence decreased significantly. However, values started to separate as the United States became less secure. Views on foreign policy, health care and gun control became so opposing to Australian views, that public opinion towards an American alliance was seen as one of convenience rather than one of shared values.

Economy. Trade with the United States becomes less lucrative, but does continue. Trade options with other nations becomes Australia’s focus for foreign affairs and trade. Australian investment in solar and nuclear energy production allows support

Fuel reserves. Diminishing economies and internal resource management made fuel exports less favourable and many governments seized control of fuel resources. Australia was able to enact on the March 2020 agreement with the US to tap into emergency reserves, however, this only lasted for 12 months before the US was unwilling to continue its support for it.[19] The government were unable to financially support private citizens and industry in support to the rising fuel costs. Defence fuel availability became unsustainable and prioritisation for capabilities became a debated topic. As a way to increase available jobs and lower fuel prices, Australia invested in oil refineries and fuel reserves. Australian investment in solar and nuclear energy production reduces the impact of economic uncertainty to the average Australian, but also allows energy support to neighbouring nations in the Archipelago, creating an energy provision dependence in Australia.

Military presence. A markedly reduced presence of United States military assets, namely US Navy freedom of navigation operations, gave more freedom for other competing powers like China. This was not exploited initially, but after 2 years of reduced US presence in the south west pacific, the People Liberation Army Navy began demonstrating uncontested movement in and around the Indo-Pacific archipelago. A requirement for a standing amphibious battle group emerged and was created through an increase to the Amphibious Task Group force assigned elements. The creation of the rotational ground combat element concept in 2018 made this manageable from a manpower and resources perspective, but became a standing readiness requirement set aside form the traditional Ready Battle Group concept. A more insular defence strategy and shortage of fuel resources made it more economic and effective to re-roll combat brigades into a light air mobile brigade based in Darwin, a heavy armoured brigade based in Townsville, and a medium motorised amphibious brigade based out of Brisbane. Deployable Joint Force Headquarters maintained its standing area of operations in the archipelago with regional partners. A forward deployable port and Amphibious Task Group Headquarters was created in Brisbane to support forward staging of naval assets on short notice to deploy to sea.

Nuclear weapon stability. Concern over nuclear proliferation grows in the media, but it is short-lived. Whilst the United States is no longer a global super power, it still has its own nuclear weapons and the nuclear armed nations all seek to maintain the status quo and prevent nuclear proliferation.

Diplomatic focus. Australia invests more heavily in the region. Increased defence cooperation programs and multinational operations become the primary focus for defence-based diplomacy. Indonesia is able to recover quickly after COVID-19 and its acceleration in terms of economic growth, but its population growth overtakes its ability to resource the nation. Australia seizes this as an opportunity and provides humanitarian and defence force support in return for forward basing provisions in Indonesia. Tourism dependence on an Australian customer base for many of the Indo-Pacific nations is realised during the Pandemic, supporting more favourable diplomacy between Australia and the Archipelago island nations.

SCENARIO: ANARCHY

Anarchy – a state of disorder due to absence or non-recognition of authority or other controlling systems.

The years following the initial Coronavirus outbreak in 2019 saw widespread rapid transmission and mutation of the virus. Failure by the general public to follow government guidance and the public’s perception that the government was not adequately addressing the problem led to anti-government protests which exacerbated the issues. With no transnational beacon shining a common path to eradication, each government attempted their own solution. All failed.

Only those who had a natural immunity or were able to survive the infection lived. Millions died, those who survived shared key genetic material or were exemplar physical specimens. Some ethnic groups were completely erased. Universally the ignorance of the government advice aimed to protect the nations had been ignored by the individuals, ever increasing restrictions heighted the resentment of the loss of individual rights. The Government’s inability to save their people undermine their position and a Hobbesian mess ensued.

The worldwide lockdowns turned societies into individuals, social cohesion was lost as individuals prioritised their desire over the needs of the many. Localised violence to obtain desirable items was widespread.

The global economy shuddered as government’s paid salaries but recouped no revenue, funded multiple failed solutions and bankrolled ever expanding health and defence budgets to deal with the increased medical and public order needs. The global financial system collapsed, with national banks being the only institutions remaining.

The demise of traditional institutions, the loss of material globalisation in exchange for virtual globalisation and the development of isolationist rhetoric led to nations purely focused on geographical preservation. Worldwide individuals were virtually connected but physically and spiritually isolated. Dating and sex became virtual experiences, relationships became online encounters, birth rates plummeted. The old, the weak and the disabled had been naturally euthanised by the pandemic. Those who had developed natural immunity, the (Genetically Superior Individuals) GSIs considered themselves elite, and quickly assumed control of all vital resources, if the World were to survive it could only be from their genetic harvest. They held all the aces and used it to their advantage.

The pre-2020 chain reaction of climate change could not be reversed; it was catalysed by the increased expenditure of single use items in the battle against infection. The habitable landscape reduced, despite populations having been reduced by the pandemic, overcrowding increased. As archipelagos disappeared under water, and some areas became too hot to inhabit internal and external migration became common place.

Those geographical countries which survived had lost all their previous identity, their institutions and governments were unrecognisable. Their populations were divided, the GSIs, the survivors, and the migrants. Their social standing followed the same ranking. The GSIs wanted for nothing, they drained the big pharma in exchange for their genetic information to create the genetic download to protect against future mutations. They had infiltrated all the new institutions and become the controlling class but only for self-fulfilment. Government as it had previously existed was gone. Rules were made to preserve the existent of the GSIs as an elite and prevent the expansion of the survivors.

The survivors hated the elite and their debauchery, they hated the migrants who had moved into their area, taken resources, caused overcrowding, and transmitted disease. They actively rebuked the system and violently clashed with migrants and each other. There was no common bond. Everyone fought for themselves. Sufficiently successful survivors who were favoured by the GSIs could seek to have the genetic download and were knowns as the Downers.

The migrants turned to violence and crime to fulfil their basic needs. The state could no longer afford to provide any welfare support, health care or education. The GSIs had made external migrants outlaws, internal migrants were an uncomfortable inconvenience. They both drained vital resources. As new strains of the disease arrived with migrants, Downers were exposed to see if the community had immunity to the strain. If they didn’t the local community was subjected to thermobaric weapons to destroy everything in that area. The morality of the importance of the GSIs life above the many migrants was never consider.

The military had become the only viable tool of the state, focused on internal public order, border control and protection against aggressors seeking resources. They had become a mercenary of the GSI, their morality replaced with promise of conversion to Downers at the end of service and high salaries. All medical and education provision had become private and were the privilege of the GSIs and survivors only. Food was grown in protected environments controlled by the GSI’s institutions using migrant slave labour. Water had become the scarcest of resources, desalination plants were the most treasured facilities and were often subject to aggression by survivor activists and migrants.

SCENARIO: COVID HERE TO STAY – WHAT IF THERE’S NO VACCINE FOR COVID-19?

As my mother blew out the candles on her 85th birthday cake, surrounded by all her grandchildren, I thanked our lucky stars that we were Australian. My mother now ranks amongst the eldest people in the world, most of which are also Australian. We are lucky to be able to have three, four and sometimes even five generations together in Australia, something that never happens anymore in the rest of the world. It is the year 2060, the median age of the Australian population is now 36 years, only one year younger than it was 40years ago. The median age in the rest of the world now stands at about 20 years old, about a decade less than it used to be before the COVID-19 pandemic. Whilst this may not seem like a significant difference, it means life expectancy in Australia is 80 years, whilst the rest of the world it’s about 62years, the same as in Africa in 2019.

Whilst most countries tried to do the right thing at the start in 2020, as the years wore on and people entered their fifth, sixth or seventh time in lockdown, populations had begun to crack. Riots broke out amongst the youth populations in Europe in 2022, they were sick of being locked up…. the resulting spike in infections saw the death toll rise three times higher than in 2020. The Italian government was worst hit, it was overthrown in 2023 and the country soon collapsed. Governments across Europe and the world eased restrictions in response, knowing that it would likely result in the loss of their elderly populations, but the alternative of mass chaos was worse.

We were lucky in Australia. It certainly wasn’t because our population was any more impressed with lockdowns, they certainly weren’t, but our government took drastic steps before we got close to the point of riots. Australia was cut off from the rest of the world (well except from New Zealand, but they don’t really count since they’re now one of our states anyway), no international flights, limited cargo ships and definitely no cruise ships, are allowed to enter Australian airspace or come within 200nm of the Australian coastline. Unfortunately, it also means Australian’s can only leave Australia with significant planning (and money) as returning to Australia requires a self paid, month long stay on Christmas Island in COVID cleansing camp; they only take new people on the first of each month so be sure to time it right.

While Australia made the right decision for our families in eradicating the disease from our shores, it required sacrifices and created significant pressure on our economy in the early days. For starters there was the huge unemployment issue, lack of incoming resources, drop in outgoing trade (as many countries refused to deal with us if we weren’t going to take their imports) and the requirement to now more closely patrol our borders.

Exemptions were made in the early years as people arrived from overseas on our shores in private yachts and chartered planes, often creating new outbreaks as they arrived, but once the Navy’s new ships were completed and we were able to patrol our waters appropriately the restrictions came firmly into place. The new patrol vessels gave purpose and work to the SA ship building program for many years following the outbreak, using local resources to construct the ships and lowering the unemployment rate significantly. The RAAF still got their aircraft from America, but they arrived surprisingly quick as so many US companies were in decline and they needed the work to prop up their failing aviation industry, pretty sure we still owe the US for them though.

The lack of incoming trade was our biggest issue though, we’d let so many industries disappear from our shores during globalisation that we had severe shortages of many things (funnily enough toilet paper wasn’t one of them). Fortunately, we have some pretty smart people in Australia, especially our creative youth. The government realised that rather than continually extending COVID welfare payments, creating an entitled generation and further alienating the unemployed sector, they should instead put their combined brainpower to use. The funding was instead funnelled into competitions, the ideas and outcomes of which could benefit society. Bored year 12 graduates discovered ways to locally refine resources. Ex-uni students created a medical assessment device which can determine levels of virus and bacteria in a user’s body. Even multigenerational welfare recipients created an education program targeting underprivileged youth from government grant money which alleviated 3 times as much from the following years welfare programs.

Our aging population in comparison to the rest of the world will make it challenging to reincorporate back into the global economy. Statistics however are noting shifts in lifestyle outside of Australia like having children younger and early retirement throughout the world as a result of the shortened life expectancy. Maybe Australia’s thriving elderly population aren’t doing so bad.

Thanks to the internet, Australia is still part of the innovative global existence, other countries carry on with their younger populations and have accepted early death as part of existence. Here in Australia we’ve protected life as well as reinvigorated innovation for our nation. While we hope to re-join the rest of the world as soon as it is safe for all of our population, in the meantime we are happy to forge our own way ahead creating new and unique concepts of our own.

Sure, we might be missing some of the cultural experiences and global economy the rest of the world presents, but Australia is now more productive, independent and proud of itself than it has ever been.

SCENARIO: MEANS OTHER THAN WAR – COULD BIOLOGICAL WEAPONS BE AN ACCEPTABLE TOOL OF WAR?

The Chairman looked around at the ministers and officials who comprised the Committee. All had earnt their place through hard work and talent, but also through a ruthlessness that ensured their survival whilst eliminating their rivals. They were adept at all forms of soft power but had the fortitude to apply hard power when required. That time had come and he knew he could count on their support.

The Chairman stood to address the Committee. ‘As you are aware, a significant milestone is approaching. It is fitting that we mark this occasion by ending the confusion as to our rightful sovereign territory and demonstrating our strength to our people and those nations who contend against us.’

Turning to the map, the Chairman continued. ‘You are all familiar with the situation here’ he said, pointing to an area that his state had long claimed as an integral part of their nation. ‘We have the military capabilities to gain an initial foothold but are likely to be repulsed at great cost by a coalition led by our major rival. In fact, they would delight in using our manoeuvring as an excuse to conduct attacks on our homeland. Heavy losses would be experienced on both sides, but the damage to our industry and the morale of our people would be unacceptable.’

‘We have long known that a purely military approach would be inadequate and have sought alternate approaches –fragmenting the alliances of those around us, influencing the inhabitants such that they willingly recognise our sovereignty and manipulating social media. But we know have a new tool that can be combined with military force to gain decisive control before a coalition can effectively contest our action’.

‘The idea was derived from the COVID-19 outbreak, when we realised the impact that a low-lethality virus could have across the globe. Previously biological and chemical weapons had been developed for lethal force and banned as tools of mass destruction. But could we design a virus to be incapacitating but have limited lethality and spread? Doctor, please provide the Committee with an update on your progress.’

The doctor rose and addressed the group. ‘I am proud to say that my team has developed a virus that will advance our nation. We have modified a form of corona virus such that it produces severe gastrointestinal distress as well as severe hallucinations. Sufferers will be incapable of operating a computer, let alone aircraft, ships or missile batteries. The expected mortality is less than 2%, in the general population well below that of the influenza virus, with mortality likely to be lower in a predominantly young and healthy population such as the military.’

‘The key aspects of this virus, however, are its initial transmission and subsequent limited spread. The virus has been designed to be carried in either an aerosol or a medium that replicates hand wash or hand sanitiser. This will ensure rapid and near complete transmission throughout the target population given the modern requirement for good hand hygiene. Symptoms will take two weeks to become apparent, thereby masking the source of the contagion and preventing detection and mitigation. But the aspect my team is most proud of, is the fact that human to human transmission is severely limited – a reproduction rate of less than 0.1. This means that infection will be limited to the target population with minimal risk to non-combatants.’

The Chairman thanked the doctor and asked the senior legal adviser to brief the Committee. ‘This is an interesting application, which is not clearly addressed in international law and has a number of precedents to support its use. Of course, our competitors will claim the use of any biological agent contravenes the Biological Weapons Convention, but arguably this is an outdated policy that requires modernisation. Given the doctor’s briefing, it is clear that the virus would not only be discriminate but also proportionate use of force. Only the target population would be affected, and the effects would be unpleasant but not lethal. In fact, their combatants would be prevented from opposing our military forces, arguably ensuring minimal casualties on both sides.’

The Chairman interjected – ‘But first they would need to establish a link between us and their unfortunate outbreak of illness. Who knows what they could have been exposed to? It would be just another unsubstantiated accusation.’

The Chairman rose and returned to the map. ‘The optimal time would be when there was a concentration of military capabilities from the informal alliance that opposes us. In six months’ time there will be a major multinational exercise intended to demonstrate their ability to contest our force projection. All key assets in the region are likely to be involved. We will need to ensure a simultaneous release of the virus medium and therefore will need to be able to manipulate their supply systems, but our network is confident that it can achieve appropriate and timely distribution to all key facilities and ships. Supply will be timed such that the virus does not manifest until after units have commenced deployment; this will complicate rescue efforts and tie up any remaining assets in the region. By the time reinforcements can be deployed from other regions, we will have established firm control of our sovereign territory and be ready to defend it against invaders. Any questions before we move to the finer details?’

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid's Tale. Vol. 301: Everymans Library, 2006.

Badger, Emily. "As American as Apple Pie? The Rural Vote’s Disproportionate Slice of Power." New York Times (2016): A11.

"The Base - Neo Nazi Extremist Hate Group." 2020, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/groups.

Beard, Jack. "The Shortcomings of Indeterminacy in Arms Control Regimes: The Case of the Biological Weapons Convention." American Journal of International Law 101, no. 2 (2007): 271-321.

Bergin, Anthony and Tony Press. “Eyes wide open: Managing the Australia-China Antarctic relationship.” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 27 April 2020. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/eyes-wide-open-managing-australia-china-antarctic-relationship

Bevan Shields, Matthew Knott. "Australia Reaches Breakthrough Deal to Buy Us Emergency Oil Supplies." Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney), 2020.

Bray, Daniel. “The geopolitics of Antarctic governance: sovereignty and strategic denial in Australia’s Antarctic policy.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 70, no.3, 2016: 256-274.

Buchanan, Elizabeth. “Antarctica: a cold, hard reality check,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 17 Sep 2019 (accessed 20 June 2020): https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/antarctica-a-cold-hard-reality-check/

Dando, Malcolm. "Biologists Napping While Work Militarized." Nature 460, no. 7258 (2009): 950-1.

Davies, Stephen, "Covid-19 and the Collapse of Complex Societies," Reason.com, 2020, https://reason.com/2020/04/16/covid-19-and-the-collapse-of-complex-societies/.

Defence Committee, “Strategic Basis of Australian Defence Policy” (12 January 1959) presented in Stephan Frühling, Australian Strategic Guidance since the Second World War: a History of Australian Strategic Policy since 1945 (Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia, 2009), 270.

Dettmer, Otto. "Covid-19 Presents Economic Policymakers with a New Sort of Threat." The Economist. (22 Feb 2020 2020). Accessed 22 Feb 2020. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2020/02/22/covid-19-presents-economic-policymakers-with-a-new-sort-of-threat.

———. "Commodity Economies Face Their Own Reckoning Due to Covid-19." The Economist. (5 Mar 2020 2020). Accessed 5 Mar 2020. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2020/03/05/commodity-economies-face-their-own-reckoning-due-to-covid-19.

Dibb, Paul and Australia. Department of Defence. Review of Australia's Defence Capabilities: Report to the Minister of Defence. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1986.

Fedunik-Hofman, Larissa. "What Impact Will Covid-19 Have on the Environment?" [In en]. Australian Academy of Science (2020/05/04/T00:14:20+10:00 2020). https://www.science.org.au/curious/earth-environment/what-impact-will-covid-19-have-environment.

Ghosh, Iman. "Covid-19: What Are the Biggest Risks to Society in the Next 18 Months?" [In en]. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/07/covid19-future-economic-societal-geopolitical-risks/.

Godfrey, Mark. “China's ‘most modern’ processing ship makes maiden voyage.” 25 May 2020, https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/chinas-most-modern-processing-ship-makes-maiden-voyage

Gothe-Snape, Jackson. “China unchecked in Antarctica.” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 12 April 2019. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-03-30/china-in-antarctica-inspection-regime/10858486

Goel, A. K. . "Looming Threat of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents." Defence Science Journal 66, no. 5 (2016): 443-44.

Groch, Sherryn. "Could Australia Eliminate Covid-19 Like Nz and How Would It Work?" [In en]. The Sydney Morning Herald (2020/07/22/T04:10:04+00:00 2020). https://www.smh.com.au/national/could-we-eliminate-covid-19-in-australia-and-how-would-it-work-20200721-p55e0k.html.

Gross, Anna. "China and Huawei Propose Reinvention of the Internet." Financial Times (London), 28 March 2020 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/c78be2cf-a1a1-40b1-8ab7-904d7095e0f2.

Gurney, Izaak. Commander’s Paper, Cold fleet: The Southern Ocean, Antarctica and the ADF. Australian Defence College, Centre for Defence and Strategic Studies, November 2016.

Halsall, Jamie, and Ian Cook. "Globalization Impacts on Chinese Politics and Urbanization." Chinese Studies 02 (01/01 2013): 84-88. https://doi.org/10.4236/chnstd.2013.22012.

Hobbes, Thomas, and E. M. Curley. Leviathan: With Selected Variants from the Latin Edition of 1668. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co, 1994.

Holdstock, Douglas. "Chemical and Biological Warfare: Some Ethical Dilemmas." Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 15, no. 4 (2006): 356-65.

Kamboj, Dev Vrat, Ajay Kumar Goel, and Lokendra Singh. "Biological Warfare Agents." Defence Science Journal 56, no. 4 (2006): 495-506.

Kellogg, Thomas E. “The South China Sea Ruling: China’s International Law Dilemma.” The Diplomat, 14 July 2016. https://thediplomat.com/2016/07/the-south-china-sea-ruling-chinas-international-law-dile mma/

Koblentz, Gregory. "Pathogens as Weapons: The International Security Implications of Biological Warfare." International Security 28, no. 3 (2003): 84-122.

———. "From Biodefence to Biosecurity: The Obama Administration's Strategy for Countering Biological Threats." International Affairs 88, no. 1 (2012): 131-48.

Koper, Keith D. "The Importance of Regional Seismic Networks in Monitoring Nuclear Test-Ban Treaties." Seismological Research Letters 91, no. 2A (2020): 573-580.

Kuper, Stephen. “Understanding Australia’s strategic moat in the ‘sea-air gap’.” Defence Connect, 18 June 2019. Accessed 12 April 2020. https://www.defenceconnect.com.au/key-enablers/4249-understanding-australia-s-strategic-moat-in-the-sea-air-gap

"Liberty State." 2017, https://libertystate.org.

McDowell, Jade. "The New State of Idaho." East Oregonian, 2015.

Moses, Asher. "‘Collapse of Civilisation Is the Most Likely Outcome’: Top Climate Scientists." [In en-US]. Resilience (2020/06/08/T13:50:19+00:00 2020). https://www.resilience.org/stories/2020-06-08/collapse-of-civilisation-is-the-most-likely-outcome-top-climate-scientists/.

Nozick, Robert. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. 1974.

Olsom, Emily. "Virginia Rally Shows What Happens When the Us Tries to Pass Gun Control Laws." Australian Broadcasting Corporation (Sydney), 2020. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-01-21/virginia-gun-rally-shows-what-happens-when-us-tries-to-pass-laws/11879410.

Orwell, George. Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984). London, England: Secker and Warburg, 1949.

Paikin, Zachary. "Greater Europe and the Future of the Global Order." Commentary, RUSI. (18 Feb 2020 2020). Accessed 02 Apr 2020. https://rusi.org/commentary/greater-europe-and-future-global-order.

Pagani, Josie. "Why We Aren’t Isolated from the Global Turmoil." Wanganui Chronicle (Wanganui, NZ), 2020/08/07/ 2020, Opinion, A10-11. https://login.virtual.anu.edu.au/login?qurl=https://search.proquest.com%2fdocview%2f2430683091%3fpq-origsite%3dsummon.

People’s Republic of China. Report of the Informal Discussion for the intersessional period of 2018/19 on the revised draft Code of Conduct for Protection of Dome A area in Antarctica. Working paper submitted for the XLII Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting, Prague, Czech Republic 2019. https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings/DocDatabase?lang=e

Ponting, Herbert George and Scott. The Great White South. Robert M. McBride and Company, 1922.

Pullinger, Stephen. "Fighting Biological Warfare." British Medical Journal 320, no. 7242 (2000): 1089-90.

Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. "Our World in Data : Age Structure." Our World in Data (2019/09// 2019). ourworldindata.org.

Robinson, Edwin S. “Seismic Wave Propagation on a Heterogeneous Polar Ice Sheet.” Journal of Geophysical Research 73, no. 2 (1968): 739-753.

Rudd, Kevin. "Time for an M7 Group of Countries to Rescue Global Institutions." The Economist. (15 Apr 2020 2020). Accessed 16 Apr 2020. https://www.economist.com/open-future/2020/04/15/by-invitation-kevin-rudd-on-america-china-and-saving-the-who.

———. "The Coming Post-Covid Anarchy: The Pandemic Bodes Ill for Both American and Chinese Power—and for the Global Order." Foreign Affairs (06 May 2020 2020).

Russian Federation. The Antarctic Treaty in the Changing World. Working paper submitted for the XLII Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting, Prague, Czech Republic 2019. https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings/DocDatabase?lang=e

Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty. “Key documents of the Antarctic Treaty System” (accessed 20 June 2020): https://www.ats.aq/e/key-documents.html

Steger, Manfred B. Globalization : A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. Book. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=264792&site=eds-live.

"Southern Povery Law Center." 2020, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/groups.

United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. "Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction." 26 March 1975 1975. http://disarmament.un.org/treaties/t/bwc/text.

Woetzel et al. China's Role in the Next Phase of Globalization. McKinsey Global Institute (Shanghai: McKinsey, 2017). https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/china/chinas-role-in-the-next-phase-of-globalization.

Xinbo, Wu. "China in Search of a Liberal Partnership International Order." International Affairs 94, no. 5 (2018): 995-1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiy141. https://academic-oup-com.virtual.anu.edu.au/ia/article/94/5/995/5092100.

Zanders, Jean Pascal. "International Norms against Chemical and Biological Warfare: An Ambigious Legacy." Journal of Conflict and Security Law 8, no. 2 (2003): 391-410.

[1]ARTICLE 1 of the Antarctic Treaty prohibits “any measures of a military nature, such as the establishment of military bases and fortifications, the carrying out of military manoeuvres, as well as the testing of any type of weapons.” However, the treaty does not prevent the use of military personnel or equipment for scientific research or for “any other peaceful purpose.”

[2]The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (the ‘Madrid Protocol’) allows changes to be considered from the 50th anniversary of ratification of the Protocol. The anniversary arises in 2048.

[3]People’s Republic of China. Report of the Informal Discussion for the intersessional period of 2018/19 on the revised draft Code of Conduct for Protection of Dome A area in Antarctica. Working paper submitted for the XLII Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting, Prague, Czech Republic 2019.

[4]Defence Committee, “Strategic Basis of Australian Defence Policy” (12 January 1959) presented in Stephan Frühling, Australian Strategic Guidance since the Second World War: a History of Australian Strategic Policy since 1945 (Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia, 2009), 270.

[5]Dibb, Paul and Australia. Department of Defence. Review of Australia's Defence Capabilities: Report to the Minister of Defence (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1986), 37.

[6]Australia’s ‘claim’ represents 42% of the Antarctic landmass.

[7]Some commentators have called for the Australian Antarctic Division to come under direct aegis of Defence, e.g. Elizabeth Buchanan, “Antarctica: a cold, hard reality check,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 17 Sep 2019 (accessed 20 June 2020): https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/antarctica-a-cold-hard-reality-check/

[9]Margaret Atwood, The handmaid's tale, vol. 301 (Everymans Library, 2006).174

[10]https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/the-sunni-arab-insurgency-a-spent-or-rising-force

[11]https://www.governing.com/topics/politics/gov-rural-voters-governors-races.html

[12]https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/09/13/partisans-differ-widely-in-views-of-police-officers-college-professors/

[13]Emily Olsom, "Virginia rally shows what happens when the US tries to pass gun control laws," Australian Broadcasting Corporation (Sydney) 2020, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-01-21/virginia-gun-rally-shows-what-happens-when-us-tries-to-pass-laws/11879410

[14]Liberty State, 2017, https://libertystate.org

[15]Southern Poverty Law Center, 2020, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/groups

[16]The Base - Neo Nazi Extremist Hate Group, 2020, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/groups

[17]Emily Badger, "As American as apple pie? The rural vote’s disproportionate slice of power," New York Times (2016).

[18]Jade McDowell, "The New State of Idaho," East Oregonian, 2015

[19]Matthew Knott Bevan Shields, "Australia reaches breakthrough deal to buy US emergency oil supplies," Syndey Morning Herald (Sydney) 2020.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.