The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the ADF, the Department of Defence or the Australian government.

What are the medium and long-range implications for Australia as a result of the US-China strategic competition, and what are our options?

Summary and recommendations

What are the medium and long-range implications for Australia as a result of the US-China strategic competition, and what are our options?

Autonomy and AI:

- Australia should decouple military strength from its relatively small population size by extensive incorporation of AI and autonomy into its fighting strength. This can be financed by significant reduction of personnel and further investment into autonomy as a Defence main effort.

Genetic augmentation:

- Competition in the 21st Century will necessitate genetic augmentation in order to remain competitive. This forms a combat multiplier that can enhance deterrence and response effects, particularly through enhancing human cognitive functions, in a faster and more complex future operating environment.

Childhood Education:

- Defence inject itself into the ‘educational eco-system transformation’ through the introduction of Defence Studies to the Australian Curriculum. This will support WoAG efforts to build domestic awareness of and resilience to malign activity in strategic competition, while also producing outstanding human-machine teams through HSI-HRI (eSports/simulation). This will effectively ‘crowd source’ R&D and inform future capability requirements, strategy, tactics and doctrine.

Regional partnerships:

- Defence should seek to revolutionise its regional engagement, moving towards ‘regional security’ in a multinational context to further enhance interoperability. This will shape the security environment in a way that increases Australia’s access and influence, deterrence and allows more flexibility in response options to a regional crisis.

- National service should be reconsidered, potentially in combination with regional security functions. This will form a mechanism whereby large portions of the general population will achieve greater cultural awareness across the region, language proficiencies, networking and overall increase social realm resilience to coercion.

Public & Private Sector:

- An urgent review and update of the public/private relationship is essential to ensure Australia has the competitive edge it needs to launch and prosecute successful campaigns in an era of increasing great power competition.

Introduction

The year is 2037. The ongoing competition between the US and China has been formally labelled as the second Cold War. Tensions have decreased slightly from their peak of 2030 and the South China Sea standoff which saw US and Chinese fleets posture against each other and come to their closest point of military action. Likened to the Cuban Missile crisis, both countries subsequently agreed to concessions and measures to prevent a recurrence, but tensions remain high. The crisis was a turning point for the Australian Defence Force. The force levels fielded by both countries and the apparent parity between China and the US forced the ADF to acknowledge that it no longer had the ability to meaningfully defend Australia against any Chinese threat and that the US would struggle to render adequate support if its own interests elsewhere where threatened. Chief of Defence Force and the Prime Minister took the decision to decouple military power from population size and personnel numbers and seek an innovative and controversial solution via the 2032 Defence White Paper. Hailed as the most significant change of policy since Federation, the paper resulted in a dramatic reduction in personnel numbers and wide scale adoption of autonomous systems and AI.

The legendary Greek hero, Odysseus, exemplified an agile and expedient form of practical intelligence; forward-looking, comfortable in uncertainty, and able to manipulate the environment as ‘a way by which the underdog could triumph over the notionally stronger.’[1] In the context of Great Power competition, Australia forms a middle power ‘underdog living with giants’ that is trying to find its place in a more complex strategic environment.[2] The ‘Odyssean approach’ must therefore underpin Australia’s strategic thinking and its approach to warfare, manipulating the environment as to remain competitive amongst the strong who vie for superior power and influence. This forms the core of what this paper seeks to address.

This paper will outline several medium-long term implications for Australia as a result of the US-China strategic competition, including options to reduce or mitigate their impact. First, this paper will briefly outline the primary implications surrounding regional Great Power competition for Australia concerning its ability to maintain regional influence; including its ability to shape, deter and respond to credible threats. These form the primary considerations that each respective option will seek to reduce or mitigate in order to enhance Australia’s relative competitive advantage. Second, as the focus of this paper, several ‘Odyssean options’ that the ADF may consider to enhance its overall competitiveness in an era of Great Power competition will be outlined. This includes genetic augmentation, creating new Defence career pathways through public education, investment in artificial intelligence and unmanned systems, innovating regional engagement the development of new partnerships between the public and private sector. Collectively, these options seek to leverage Australia’s relative strengths and opportunities while mitigating weaknesses and threats. The paper contends that superior execution of these options relative to other actors will result in Australia maintaining a regional competitive advantage, despite its middle power underdog status.

By 2036, the ADF had reached its agreed steady state size of 1000 personnel acting predominantly as supervisors and decision makers monitoring the highly automated quick reaction defence capability (QRDC) and border patrol force (BPF). Navy, Army and Air Force had been abandoned in favour of a singular ADF organisation. At sea, on the ground and in the air, unmanned systems patrol continuously in a seemingly random pattern. In reality, the AI controlled paths are carefully designed to provide a robust mesh of presence such that any point within the continent can be visited within an agreed period of time. Currently this is 30 minutes for the littoral and 1 hour in land. Any contacts of interest are automatically intercepted and interrogated by the patrol systems wherein anomalies are relayed to the control centre for human guidance.

Implications for Australia - US-China strategic competition

The medium-long term implications of US-China competition are many and varying; however, the following are considered those that will remain enduring and become increasingly challenging and of most consequence when considering Australia’s options.

Strategic geography

Strategic geography in Great Power competition is important for states in clarifying the scope of their interests and their commitments to allies, neutral parties and adversaries.[3] Actors may also seek to turn common territory into ‘denied areas’ as to expand their influence or preserve the capacity to transition rapidly to armed conflict at a time of their choosing.[4] The ADF must seek to increase its levels of regional influence and access to strategic geography. This will require more military engagement, new capabilities and different force postures to maintain multinational interoperability and situational understanding.

Military modernisation

Military modernisation is impacting Australia’s security in three fundamental ways: first, reducing Australia’s relative capability edge; second, compressing the operating environment and degrading the protection once afforded by unique strategic geography; and third, decreasing the warning times and indicators for possible contingencies.[5] This will require the ADF to maintain regional force postures of higher readiness with various follow on sustainment implications.[6] It also compels the ADF to consider radical technologies that offer the greatest ‘leap ahead’ potential, to limit the scope for other actors to achieve technological parity.

Diminishing national power (population and economy)

Australia will increasingly experience relative diminishing national power in terms of its population and economy into the future. By 2050, Asia will hold 60% of the global population while China alone will account for 20% of world GDP as the world’s largest economy, followed closely by India and Indonesia.[7] In contrast, Australia’s economy will decrease significantly in overall GDP rankings.[8] These constraints will need to be offset by innovative security strategies that reduce or replace current human functions while simultaneously increasing the persistence of military effects across the operating environment. This includes supporting the ability to scale-up forces as threat levels increase. Put simply, this means doing more with less. Prioritising investment in capabilities that maximise strategic ambiguity as a means of deterrence should also be considered.

The social realm

Australians have typically viewed the social realm as distinct from strategic competition and conflict, reflected by security policy and practices that remain separated from domestic politics and society.[9] However, as information and communication technologies continue to advance, society will be increasingly targeted by malign interference and coercion.[10] This will require the ADF to critically consider the nature of its relationships and interactions with the domestic population, potentially as an instrument of counter-interference and building population resilience. Given that Australian public awareness of Chinese coercion has increased substantially in the last two years, (only 23% of Australians now trust China to act responsibly in the world),[11] Defence potentially holds more opportunity than ever to engage with and influence the domestic population.

Divergence of ethics and values

The divergence of ethics and values between China and the West will continue to be a source of tension and barrier to mutual understanding.[12] Over the medium-long term, this may become more pronounced as Great Power competition intensifies and more urgently seeks forms of advantage through their policies and actions. This particularly relates to aspects such as military operations and technological research and development. This will require the ADF, as a values-based organisation, to critically consider how it can undertake both while remaining competitive against other actors who may not be similarly constrained by ethical considerations.

Australia’s Odyssean Options

Genetic Augmentation in the Century of Great Power Conflict

An unknown seaborne vessel is detected approaching Jervis Bay by one of the high altitude solar powered pseudo satellites. The AI determines the best course of action and sends a signal to one of the high-speed armed interceptors currently hanging on an overhead power cable recharging its cells.[1] The interceptor de-latches from the high voltage cable and is airborne within seconds. On arrival, it determines the contact to be a pleasure craft deviating from its intend course, no further action is required and it returns to shore to find another power cable to continue its charge cycle.

The great power competition over the 21st Century will encompass genetically engineered humans in both a warfighting and support capacity. It will come from either a self-generated capability to provide an edge over the opponent and thus spur the other competing actors to follow suit, or as a requirement to manage the human-technology interface that current human biology and psychology cannot currently support.

As this level of understanding expands to the animal kingdom, the genes that allow for cheetahs to run over a hundred kilometres per hour, the owl to see a mouse from hundreds of metres away on a moonless night, or whales that sleep with just one half of their brain at a time, can be integrated into the human genome.

Aside from the economic value in securing the technology that could influence everything from food production, medical tourism to the cure for cancer, the nation that develops 'super-soldiers' will hold a qualitative superiority over the opponent. It is not just more durable and faster troops on the ground, it is analysts with eidetic/photographic memory, systems operators able to integrate with quantum computing or the commander who copes without sleep for weeks at a time. This will become a requirement for using printed drones or rapid adaptation of emergent technologies during more competitive phases of great power competition.

As the genetic coding of the animal kingdom is mapped for scientific purposes, this knowledge is then co-opted by state and non-state actors who do not have the resources for a holistic approach, but do have the resources and will to pick the genes that will enhance the capabilities they are seeking to improve.[13] It advances the desires of the actor without investment.

Concurrent with the growth of biological understanding, the increasing speed of weaponry and computing will begin to exceed the ability of the human mind to comprehend and react. New weapons and capabilities will require the interface between system and operator to become more tightly integrated. The early identification of individuals with the biological markers necessary to integrate above competitors is critical. Both public/private partnerships and educational relationships are necessary to become a part of successful strategy in bio-competition.[14]

The aerial units comprise a mixed fleet of lightly armed patrol units capable of alighting on and recharging from designated charge points or high voltage electricity cables. The high-altitude pseudo satellite platforms provide airborne surveillance and early warning as well as communication relay.[1] These are solar powered and remain aloft for months at a time. Fast attack jets carry out shorter range patrol activity but must refuel at designated small installations, landing vertically and autonomously. Heavier strategic bomber capabilities exist but in much smaller numbers and are supplemented by an extensive long-range missile stockpile distributed in key locations around the country but focused in the north.

As China and the United States compete across economic, power and influence metrics throughout the globe, any advantage will be pursued. Commercial interests will drive the development in the latter as ethical norms, and legalities will directly impede the progress of engineered humans part of any government enterprise. Over time the normalisation of genetic adaptation will weaken the norms that constrain open development. Commercial interests will require the first evolved humans, controlling the fleets of drones, autonomous vehicles and information communication systems. A smaller conflict will test the early engineered humans. The competition between the two great powers will ensure that neither side can afford to be disadvantaged. Initially, this occurs through gene splicing on natural-born humans, until the most significant gains are to be found during embryonic development.

However, a system must be found in which mobilisation includes not just putting civilians in uniform, but also equipping them with the augments they need to operate in the conflict. Individuals will be screened upon entering the military force, looking for the areas in which the most significant enhancements can be developed in the most efficient time. An individual's biological adaptation is akin to cognitive aptitude; their role is decided by their biology and enhanced as such. The nature of the great power competition is stable; however, as the normative constraints are removed, gene editing will become more commonplace and adaptable. Before birth, humans in developed countries are genetically screened and pre-dispositions toward mental and physical disease treated. This technology becomes dual-use. Genetic markers ideal for augmentation flag the child as 'pre-mobilised'. Their augmentation is completed for state service however is rendered 'dormant', activated only upon joining the force either through volunteer service or conscription. These individuals are given certain societal benefits befitting their utility if a conflict occurs. Expensive treatments for significant injuries or diseases are paid for by the state to 'protect' those who can have their augments activated at short notice.

Much like many of the technological aspects of war in the 21st Century, those actors that do not embrace the means to compete will be at a qualitative disadvantage that the quantitative technological advantages, such as printed unmanned systems, cannot compete with. The cognitive and biological means to operate these systems will mandate augmentation. Ethical constraints will be subject to national security in a highly competitive environment. The economics will provide an opportunity that cannot be ignored.

The maritime fleet similarly comprises a range of capabilities. By far the largest in terms of numbers are the autonomous patrol craft. Powered by highly efficient flow cells,[1] these undertake patrols on designated tracks as dictated by the defence AI, then return to the nearest compatible berth where they autonomously dock and recharge.[1] They carry a complement of the same armed patrol aerial units as well as one attack jet. Their armaments include directed energy weapons,[1] and short-range missiles for self defence or small target engagement. Larger silo ships are conventionally powered and serve as a mobile silo for long range missiles but feature only limited self defence capability.[1] These do not carry out patrol tasks and remain secured at the naval bases until required. On deployment, they must be accompanied by protection vessels. Larger basing vessels have the ability to carry and refuel squadrons of attack jets or bombers. Again, these remain at port facilities until required. Underwater, long range submersible patrol craft surveil the coast and approaches for submarine activity. This is supplemented by an extensive hydrophone, EM detection and sonobouy network.

Starship Troopers meets Enders Game - revolutionising Australia’s education system

Two government organisations; the Department of Defence and Innovation and Science Australia (ISA), each possess science, technology and innovation strategies for 2030.[15] The former is premised on Defence Science and Technology (DST) better coordinating the national S&T enterprise to support Defence, including publicly funded research agencies (PFRAs), universities, private industry and entrepreneurs.[16] The latter outlines the evolution of the Australian Curriculum for STEM-subjects that will become completely informed by industry as a means for equipping Australians with relevant 21st century skills and maintaining Australia’s competitiveness in the global innovation race.[17] This provides opportunities for Defence.

By 2050, the above strategies can be completely aligned, with two potential outcomes for Defence: first, Defence can act as a primary informing agency for the Australian STEM Curriculum; and two, more radically, ‘Defence Studies’ could form part of the Australian Curriculum.[18] Overall, these two outcomes would result in the early identification, development and attraction of talent to provide Defence a significant competitive advantage.

Defence as an informing agency

Defence as an informing agency for the Australian STEM Curriculum could shape childhood learning to better suit prospective careers across the entire Defence enterprise; for example, military or civilian roles within the ADF, DSTO or Defence Industry. Additionally, to even further leverage this opportunity, Defence could fund scholarships to promising students in STEM fields as a means of developing and attracting talent. Overall, regardless of whether students ultimately pursue careers in Defence, this would form a strong means of community engagement that enhances Defence reputation, promotes greater understanding of Defence amongst the general population, and builds latent potential in the Australian workforce to pursue careers later if they desire.

Defence Studies

The latest update to the popular free to download game series Call of duty - Future War is a success with over 10 million downloads internationally. The Melbourne Thrashers compete with the London Bandits and the Seoul Soldiers in the final of the e-sports championship to determine who will be crowned Future War champions. After a superlative performance which included an ingenious flanking manoeuvre followed by interspersed waves of maritime and airforce air attacks and an unexpected alliance with the Seoul Soldiers, the Thrasher’s forces clinched the victory over the Bandits defences in the Indonesian archipelago. CDF presents the winners medals before retiring to his staff car where an urgent briefing notifies him of the latest Chinese escalation against the US fleet in the South China sea.

In transforming the Australian education system to be ‘future ready’, the introduction of Defence Studies could form a technical and vocational education and training (TVET) or high-school elective subject.[19] This would be supplemented by a standard STEM based curriculum as a pre-requisite for those undertaking a Defence scholarship. Underpinned by a strong understanding of the ADF role, ethics and values, military history and the Australian strategic environment, the core focus of Defence Studies is practical based: the application of strategy and tactics through Human-System/Human-Robot interaction (HSI-HRI) utilising ADF capability within a simulated environment.[20]

The pace of modern conflict requires a mission-command construct for executing multi-domain battle.[21] For future conflict, occurring at machine speed and mutually inclusive of HSI-HRI, this will become even more critical as decision-making and reaction times gradually diminish to challenge human capability.[22] Accordingly, the ADF will require command structures and systems comprising over ever smarter humans and effective human-machine teaming. If implemented to a superior standard than our competitors, this will yield an unparalleled decision advantage within the operating environment.[23] Therefore, shaping the national education system to produce students who excel in human-machine teaming and attracting them to Defence will provide the ADF with the greatest chance of achieving this competitive edge. Practically, the above would be produced through an ADF system generating a multi-domain simulated environment akin to e-Sports or competitive gaming.[24] This not only appeals to the targeted demographic, but provides the necessary tools and environment to develop and assess strategy, tactics and decision-making to improve human talent and human-machine teaming, while simultaneously enabling the contestation of ideas.

Specifically, Actions Per Minute (APM) is a video game metric that measures how many actions a player performs per minute, most applicable to real-time strategy (RTS) games where players are required to live multi-task.[25] An ‘action’ involves a single mouse or key stroke, with professional RTS players exceeding 800 APM at peak moments of gameplay. This represents both intuitive (through extensive experience and habit) and deliberate micro-decision-making being executed via HSI; or otherwise put, 800 decisions or HSI interactions per minute (DPM/HSIPM). In strategic competition, the military actor that first develops such HSI to produce its battlespace effects, coupled with human-machine teaming excellence, will dominate the operating environment. Accordingly, not only should this be a major focus for Defence R&D, but it should form part of the national education system to produce the most outstanding human-machine teaming possible, while enhancing Defence reputation and educating the social realm as a means of building national resilience to coercion and malign actors.

With tensions crossing thresholds, CDF calls the PM who authorises an operational scale up. Coverage of patrol response times is reduced. Triggered by the notice reduction, across Australia, storage facilities blink into life, charging circuits activate for the reserve squadrons taking them from a storage to active loads. The QRDC is at maximum readiness but it is not sufficient for full scale hostilities with an adversary like China. The national cabinet authorises an increase in force levels to match the threat profile. Under the Government-Critical Industry Strategic partnership, production lines and factories engaged in normal commercial activity are repurposed into their military role. The last test of these part-government funded production lines in 2030 showed that a full re-role can be achieved within 36 hours. Materials and components not normally used in the commercial activity but required for military production are called forward from the adjacent warehouses. Reservists are called up, but these are not military, they are factory workers there to oversee the highly automated lines that nevertheless still require some human actions and occasional intervention. Production of maritime, air and land assets ramp up to maximum capacity and consideration is given to operation SURGE which looks to repurpose non-partnered civilian facilities, but this is deemed not yet necessary.

Diplomacy through regional multilateral service

Recent events like ISIS cells occupying and operating in portions of the Philippines, and the Covid-19 Pandemic influence on the economy has sent clear messages to the people about the fragility of Australia’s security. Moreover, the Covid-19 Pandemic has reminded Australians that we are heavily influenced by the actions of the US and China. For Australia to build resilience against this it needs to develop its own strength.

Patriotism and partnerships can foster beneficial power. To increase the population's awareness of regional security and build national pride the concept of compulsory school leavers regional security National Service could be introduced. Many international models have shown that two years of service following high school studies improves population confidence, and sense of belonging. The concept offered in this document is national service, conducted at regional security posts, shared with partner nations. For example, ASEAN nations could contribute personnel to this effort. The benefits would include increased cross communication, cultural understanding, and relationship building. If each contributing Nation developed a regional outpost each nation could contribute to the security workforce.

The top 1000 players in Future War across all allied nations are notified to report to their nearest HQ where they will be given a classified briefing. There they will be notified that the interface for Future War, which they have mastered, is the same as that required to operate the real allied forces.[1] The game had been designed to be as realistic as possible with built in ROE and legal considerations. The briefing is therefore mainly to inform the players that this is now real and to in brief them on intelligence elements that were not featured in the game and to revise the weapon capabilities to reflect real life. A few players decline the invitation to fight for their country, but the majority see this as just another level in the game and gladly accept the responsibility. The pre-existing ADF hierarchy will retain oversight, the new players will take closer control of specific squadrons and mission sets.

A New Type of Partnership: Public-Private Sector Cooperation

The ideas throughout this paper will require many changes in the contemporary environment to ensure they reach their full potential. Among the most pressing is the relationship between the public and private sector in Australia.

The private sector is a key element of national power. Without it, Australia could not sustain its population, let alone progress futuristic initiatives in areas such as human augmentation and video game integration. Some enterprises are so critical that it is in the national interest to ensure their survival at all costs.[26] This will become increasingly vital as our region becomes more competitive and Australia needs to become more self-reliant.[27]

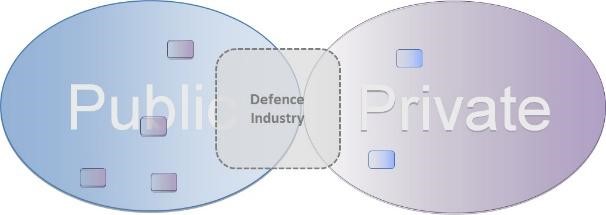

Australia has limited capacity to sustain itself in times of strategic competition.[28] The current public-private relationship is strong but not sufficient to meet future challenges. Figure 1 illustrates the current relationship, which features a strong Defence industry at the public/private nexus, skewed towards the private sector working in the public sector. There are a number of ‘satellite’ initiatives beyond the core Defence industry, such as research & development. Defence has some inroads into the private sector (e.g. industry placements) but these are minimal.

The major problem with the current relationship is that it is viewed as a commercial contract in many ways; where goods and services are exchanged for money and the onus is on the public sector to know what to ask for. In an era of strategic competition, the public sector may not know what it needs until it is too late.

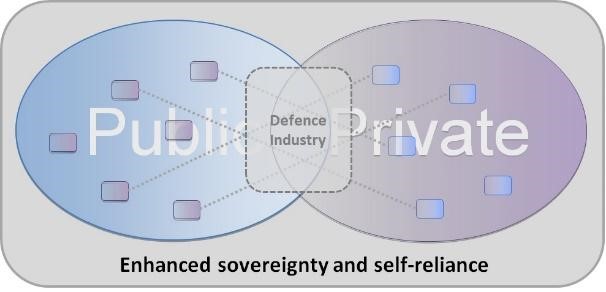

Figure 2 illustrates the public-private relationship that is necessary to meet future challenges. Defence industry remains the central hub; however, it is supported by more satellite collaborations. These collaborations, when orchestrated in a networked fashion, strengthen the bond between sectors and draws them together, forming an impenetrable relationship that enhances national sovereignty.

The greatest change will be to deepen public sector links into the private sector. Target areas for this proposal are industries that are critical to national sovereignty in times of crisis (such as energy, manufacturing, logistics, medical and security). Options to achieve this are many and may include: secondments of public officials in private companies (similar to industry placements but deeper and focussing on the companies’ role in national sovereignty); a targeted national service program where positions in companies are bestowed a public sector role in a crisis (e.g. CEOs of select companies could be granted Senior Executive Service status in emergencies);[29] tax and/or other financial concessions for participating companies accompanied by long-term, deeper contractual relationships to incentivise private sector buy-in.

The first shots are fired by the Chinese forces in the South China sea against US vessels. Unmanned vessels take the brunt of the damage, but some manned vessels are also hit. The loss of life triggers a declaration of war. ANZUS Plus and NATO Article 5 are invoked; the allied network forms immediately as AI systems across all the participating nations commence handshake and authentication procedures. The allied response will be overwhelming.

These options are a small sample of what could be possible. This initiative would enhance sovereignty and self-reliance through increased collaboration in critical industries. Australia would have greater national unity of effort and quicker response times when executing campaigns in strategic competition, which would enhance national resilience at a time where it has never been more important.[30]

Ainscough, Michael J. “Next Generation Bioweapons.” Counterproliferation Paper Series, no. 14 (2002): 1–38. http://farmwars.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/nextgen.pdf.

Almeida, Maria Eneida de. “A Permanente Relação Entre Biologia, Poder e Guerra: O Uso Dual Do Desenvolvimento Biotecnológico.” Ciencia e Saude Coletiva 20, no. 7 (2015): 2255–66. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015207.13312014.

"APM Definition." TechTerms: The Computer Dictionary, 2020, accessed 18 August 2020, https://techterms.com/definition/apm.

Barrie, Chris. "AUSS+IE – Why Australia Needs a Universal Service Scheme." In Centre of Gravity Series, edited by Andrew Carr, 33-41.

Strategic & Defence Studies Centre: Australian National University, 2020.

Bell, Coral. Living with Giants: Finding Australia's Place in a More Complex World. Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2005.

Bisley, Nick, and Andrew Phillips. "Rebalance to Where? Us Strategic Geography in Asia." Survival 55, no. 5 (2013): 95-114.

Blaxland, John. "A Geostrategic Swot Analysis for Australia." (2019).

Brabin-Smith, Richard. Future Challenges and a New Defence Policy. The Centre for Gravity Series: Why Australia Needs a Radically New Defence Policy. Strategic & Defence Studies Centre, ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, October 2018, 2018.

Cooper, Alastair. Closer, Faster, Harder - Australia’s Strategic Geography. Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 9 April 2018, 2018.

Department of Defence. 2016 Defence White Paper. Canberra: Department of Defence, 2016.

Department of Defence. Defence Strategic Update. Canberra: Defence Publishing Service, 2020.

Department of Defence. Addp 3.0 Campaigns and Operations. Operations Series. Canberra ACT 2600: Defence Publishing Service, 2012.

Department of Defence. More Together: Defence Science and Technology Strategy 2030. Canberra: Department of Defence, 2020.

Dibb, Paul. "Is Strategic Geography Relevant to Australia's Current Defence Policy?". Australian Journal of International Affairs 60, no. 2 (2006): 247-64.

Dibb, Paul, and Richard Brabin-Smith. Australia's Management of Strategic Risk in the New Era. Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2017.

Freedman, Lawrence. Strategy : A History. Oxford, UNITED STATES: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2013.

Grattan, Michelle. "Morrison Aligns Defence Policy with New Reality as Australia Muscles up to China." The Strategist, 08 July 2020. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/morrison-aligns-defence-policy-with-new-reality-as-australia-muscles-up-to-china/.

Hamari, Juho, and Max Sjöblom. "What Is Esports and Why Do People Watch It?". Internet Research 27, no. 2 (2017): 211-32. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-04-2016-0085. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-04-2016-0085.

Harris, Stuart. China's Foreign Policy. Oxford, UNITED KINGDOM: Polity Press, 2014. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/anu/detail.action?docID=1729548.

Hawksworth, John, Hannah Audino, and Rob Clarry. "The Long View: How Will the Global Economic Order Change by 2050." (2017).

Hechavarría, Rodney; López, Gonzalo. “Introduction to Strategic Foresight.” Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 53, no. 9 (2013): 1689–99. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Innovation and Science Australia. "Australia 2030: Prosperity through Innovation. A Plan for Australia to Thrive in the Global Innovation Race." Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, Australian Government, 2017.

Kassam, Natasha. "Great Expectations: The Unraveling of the Australia-China Relationship." (20 July 2020 2020). Accessed 22 August 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/great-expectations-the-unraveling-of-the-australia-china-relationship/.

Kuper, Stephen. "Falling Well Behind the Curve: Australia Ranks Last in Global Self-Sufficiency Ranking." Defence Connect, 31 July 2020. https://www.defenceconnect.com.au/key-enablers/6557-falling-well-behind-the-curve-australia-ranks-last-in-global-self-sufficiency-ranking.

Mansted, Katherine. Activating People Power to Counter Foreign Interference and Coercion. Policy Options Paper. Vol. 13, Canberra: National Security College, Australian National University, December 2019, 2019.

Murphy, Robin, and James Shields. "The Role of Autonomy in Dod Systems." Defense Science Board Task Force Report (2012): p13.

United Nations. World Population Prospects 2017 – Data Booklet. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017 2017).

Osinga, Frans. Science, Strategy and War - the Strategic Theory of John Boyd. CW Delft, Netherlands: Eburon Academic Publishers, 2005.

Pison, Gilles. "The Population of the World - 2019." Population & Societies 569, no. 8 (2019): 1-8.

Roberts, Anthea, Henrique Choer Moraes, and Victor Ferguson. "Geoeconomics: The Variable Relationship between Economics and Security." Lawfare, 27 November 2018. https://www.lawfareblog.com/geoeconomics-variable-relationship-between-economics-and-security.

Taylor, Jacob. "What Resilience Really Means as a Guide for Australian Policymaking." The Interpreter, 09 July 2020. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/what-resilience-really-means-guide-australian-policymaking.

US Army, Training and Doctrine Command. "Multi-Domain Battle: Evolution of Combined Arms for the 21st Century, 2025-2040." Washington, DC: US Department of Defense, Version, 2017.

Waxman, Matthew, and Kenneth Anderson. "Law and Ethics for Autonomous Weapon Systems: Why a Ban Won’t Work and How the Laws of War Can." Hoover Institution Task Force on National Security and Law 9 (2013): 4-5.

World Economic Forum. "Realizing Human Potential in the Fourth Industrial Revolution: An Agenda for Leaders to Shape the Future of Education, Gender and Work." 2017.

[1]Lawrence Freedman, Strategy : A History (Oxford, UNITED STATES: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2013), 24-29.

[2]Coral Bell, Living with giants: Finding Australia's place in a more complex world (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2005).

[3]Nick Bisley and Andrew Phillips, "Rebalance To Where? US Strategic Geography in Asia," Survival 55, no. 5 (2013): 98.

[4]US Army Training and Doctrine Command, "Multi-domain battle: Evolution of combined arms for the 21st century, 2025-2040," (Washington, DC: US Department of Defense, Version, 2017), 7.

[5]Alastair Cooper, Closer, faster, harder - Australia’s strategic geography (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 9 April 2018, 2018); Paul Dibb, "Is strategic geography relevant to Australia's current defence policy?," Australian Journal of International Affairs 60, no. 2 (2006): 253; Department of Defence, 2016 Defence White Paper (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2016), 49-50; Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith, Australia's Management of Strategic Risk in the New Era (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2017), 2.

[6]Richard Brabin-Smith, Future Challenges and a New Defence Policy, The Centre for Gravity Series: Why Australia Needs a Radically New Defence Policy, (Strategic & Defence Studies Centre, ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, October 2018, 2018), 9-10.

[7]United Nations, World Population Prospects 2017 – Data Booklet, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017 2017), 3; Gilles Pison, "The Population of the World - 2019," Population & Societies 569, no. 8 (2019): 6; John Hawksworth, Hannah Audino, and Rob Clarry, "The long view: how will the global economic order change by 2050," (2017): 5-7.

[8]Hawksworth, Audino, and Clarry, "The long view: how will the global economic order change by 2050," 7.

[9]Katherine Mansted, Activating People Power to Counter Foreign Interference and Coercion, vol. 13, Policy Options Paper, (Canberra: National Security College, Australian National University, December 2019, 2019), 2.

[10]Mansted, Activating People Power to Counter Foreign Interference and Coercion, 13, 2.

[11]Natasha Kassam, "Great expectations: The unraveling of the Australia-China relationship," (20 July 2020 2020). https://www.brookings.edu/articles/great-expectations-the-unraveling-of-the-australia-china-relationship/.

[12]Stuart Harris, China's Foreign Policy (Oxford, UNITED KINGDOM: Polity Press, 2014), 14. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/anu/detail.action?docID=1729548.

[13]This is of great use to smaller and weaker states. For example, North Korea could render their agents immune to the biological weapons they carry in targeted assassinations. Criminals could render their courier’s memory ‘blank’ upon a certain trigger, from which they cannot provide evidence in prosecution.

[14]For example, the manner in which those most capable of integrating across advanced systems will be self-evident through competition. Online gaming already identifies who has the necessary reactions and a tactical edge against adversaries in high speed competitions. Integrating this into schooling is a strategic level initiative, undertaken in concert with corporate sponsors and the education system.

[15]Department of Defence, More Together: Defence Science and Technology Strategy 2030 (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2020); Innovation and Science Australia, "Australia 2030: Prosperity through innovation. A plan for Australia to thrive in the global innovation race," (Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, Australian Government, 2017).

[16]Defence, More Together: Defence Science and Technology Strategy 2030, 2.

[17]Innovation and Australia, "Australia 2030: Prosperity through innovation. A plan for Australia to thrive in the global innovation race."

[18]This is almost a reality. In 2019, Playford International College in South Australia achieved approval in principle from the education department to implement ‘Defence Studies’ as an elective subject for their students. Unfortunately, COVID has halted this progression through lack of Defence-community engagement in 2020.

[19]For detailed discussion on transforming educational eco-systems to be ‘future ready’, from early education through to revolutionising TVET, see World Economic Forum, "Realizing human potential in the Fourth Industrial Revolution: An agenda for leaders to shape the future of education, gender and work" (2017).

[20]Human-robot interaction (HRI) is a field focussed on examining how people work or play with robots, including cognitive interactions whereby the robot operates at a distance from the user. Scope includes unmanned systems, psychology (critical-thinking and decision-making), human-robot teamwork and communication, human computer interaction and sociology. This is a subset of the larger field of human-system interaction (HSI), that addresses computers and tools more broadly. See Robin Murphy and James Shields, "The role of autonomy in DoD systems," Defense Science Board Task Force Report (2012): 44.

[21]US Army Training and Doctrine Command, "Multi-domain battle: Evolution of combined arms for the 21st century, 2025-2040," (Washington, DC: US Department of Defense, Version, 2017), i.

[22]See generally Matthew Waxman and Kenneth Anderson, "Law and ethics for autonomous weapon systems: Why a ban won’t work and how the laws of war can," Hoover Institution Task Force on National Security and Law 9 (2013).

[23]This is the concept would essentially be the evolution of Boyd’s OODA Loop, see Frans Osinga, Science, Strategy and War - The Strategic Theory of John Boyd (CW Delft, Netherlands: Eburon Academic Publishers, 2005).

[24]eSports is as ‘a form of sports where the primary aspects of the sport are facilitated by electronic systems; the input of players and teams as well as the output of the eSports system are mediated by human-computer interfaces.’ See Juho Hamari and Max Sjöblom, "What is eSports and why do people watch it?," Internet Research 27, no. 2 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-04-2016-0085, https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-04-2016-0085.

[25]"APM Definition," TechTerms: The Computer Dictionary, 2020, accessed 18 August 2020, 2020, https://techterms.com/definition/apm.

[26]Anthea Roberts, Henrique Choer Moraes, and Victor Ferguson, "Geoeconomics: The variable relationship between economics and security," Lawfare, 27 November 2018, https://www.lawfareblog.com/geoeconomics-variable-relationship-between-economics-and-security.

[27]Michelle Grattan, "Morrison aligns defence policy with new reality as Australia muscles up to China," The Strategist, 08 July 2020, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/morrison-aligns-defence-policy-with-new-reality-as-australia-muscles-up-to-china/; Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Update (Canberra: Defence Publishing Service, 2020), 26.

[28]Stephen Kuper, "Falling well behind the curve: Australia ranks last in global self-sufficiency ranking," Defence Connect, 31 July 2020, https://www.defenceconnect.com.au/key-enablers/6557-falling-well-behind-the-curve-australia-ranks-last-in-global-self-sufficiency-ranking.

[29]Chris Barrie, "AUSS+IE – Why Australia needs a universal service scheme," in Centre of Gravity Series, ed. Andrew Carr (Strategic & Defence Studies Centre: Australian National University, 2020), 33.

[30]Jacob Taylor, "What resilience really means as a guide for Australian policymaking," The Interpreter, 09 July 2020, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/what-resilience-really-means-guide-australian-policymaking.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.