'The importance of play has been recognised in all cultures; it has been widely studied and endorsed in the human sciences and demonstrated in practice in enlightened schools throughout the world. And yet the standards movement in many countries treats play as a trivial and expendable extra in schools – a distraction from the serious business of studying and passing tests. The exile of play is one of the great tragedies of standardised education.'

Sir Ken Robinson, Creative Schools1

'Why, while the clouds of war thickened above them, would a group of serious-minded, middle-aged men waste their time on a board game?'

Simon Parkin, A Game of Birds and Wolves2

The Intellectual Edge, play, and gaming

In An Australian Intellectual Edge for Conflict and Competition in the 21st Century Major-General Mick Ryan cites the work of Dima Adamsky, which highlights the need to focus on ‘military software’ or the intellectual preparation of military forces.3 Major-General Ryan identifies a military software gap that ‘can result in a failure of imagination, a failure to anticipate and a failure to learn and adapt’. He proposes that the Australian Defence Force (ADF) must not focus only on technological advantage, which are likely to be met or diminished by the rapid advances in technology. A small force, like the ADF, must focus on developing an advantage via the ‘intellectual edge’ through individual professional mastery and institutional practice.4

The development of an intellectual edge is founded on several educational initiatives such as a focus on continuous learning and guided self-development, and focused on technological initiatives such as accessibility, innovative engagement and delivery, and augmented cognition.5 Many of these initiatives can be enhanced and complemented by gaming and learning through play. As Sir Ken Robinson’s words demonstrate, there are myriad publications and studies that emphasise the importance of play in educating children. In the last two decades, there has also been emphasis on ‘serious games’ and ‘edutainment’ that are focused on using games to educate adults through play.6 Studies have highlighted the potential benefits of games to education, which include ‘improved self-monitoring, problem recognition and problem solving, decision-making, better short-term and long-term memory, and increased social skills such as collaboration, negotiation, and shared decision-making’.7

Games – both tabletop and electronic – can be considered as alternative pedagogical approaches to traditional avenues focused on lectures and seminars when games are incorporated lesson plans to achieve learning objectives. Games offer a means by which students can play with the content and concepts presented to them in lectures and seminars. This can be achieved through games that focus on war and military concepts- commonly called ‘war games’. These games can enhance learning through the development of tactical insight and planning, and to test military plans through simulation. Further, other non-military games may offer learning outcomes about leadership, strategy, and tactics through abstract game concepts and mechanics. Contrary to the rhetorical question posed by Parkin, time spent in gaming to enhance and complement other education methods is not wasted. In the ADF context, the key is to ensure that the game selected is appropriate for the learning objectives and outcomes at each level of the Australian Joint Professional Military Education Continuum, which is Australia’s system to develop mastery in the Profession of Arms and aims to cultivate an intellectual edge.8 More work is required in finding games that can enhance and complement the learning objectives in various ADF courses. This overview is intended as a short introduction to the history of games in military education and training.

Overview – from the Magdeburg War Gaming Society to ‘This War of Mine’ (2017)

‘In the hands of men with military experience the game Kriegsspiel is a means of acquiring a science which, in time of peace, cannot be easily acquired’.

The Graphic, 10 August 1901, p. 1869

The use of games as part of PME is not new but is no longer a regular part of PME.10 War games provide for education and training in tactics and operations, and also to simulate or test military plans. In the 19th century,war games became a central feature of military education. A civilian, Herr von Reisswitz, invented Kreigsspiel (figure 1). He provided a demonstration of a prototype of the game to Princes Wilhelm and Friedrich in 1811.11

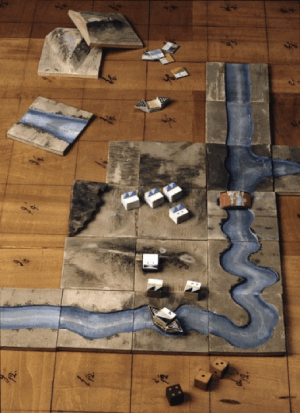

Figure 1 – The original Kreig Spiel (image from Board Game Geek).

A mature version of the game was demonstrated to the King in 1812. Reisswitz’s son continued to develop the game while he served as a lieutenant in the Guard Artillery Brigade in Berlin. He continued to develop the rules and played the game regularly with a group of fellow officers. Popularity of the game ultimately spread throughout the army after it was demonstrated to the then chief of the general staff, General von Müffling, who said: ‘This is not a game! This is training for war! I must recommend it to the whole army.’12

Although the game had its own detractors that argued that it would mislead young officers by providing them with an unrealistic belief that they could lead large forces, the game was popular because it was perceived as a useful means to understand tactics via an engagement between two armies on a map. Moves were limited into 2-minute intervals in which a player could move, fire, or use melee attacks. It required a minimum of three players but could accommodate up to six. One of the players was the umpire and provides the players with limited situational awareness (a ‘general idea’ of the game and the objective of each side) and maintained a tally of losses. The umpire also provided each commander with a ‘special idea’ that was unique to them and provided information about their immediate objective and intelligence regarding disposition of the enemy.13 Dice were used to determine the results of an engagement and simulated the role of chance in war.14

The game continued to grow in popularity throughout Prussia and clubs were formed to play it. This included the Magdeburg Wargaming Club founded in 1828 by then Lt. Helmuth von Moltke. He remained an enthusiastic supporter and advocate for the game, even after he became a general.15 The British ultimately took interest in the game after the Prussian success in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.16 The explanation for this increased interest ‘may be, in some measure, due to the feeling that the great tactical skill displayed by Prussian Officers in the late war had been, at least partially, acquired by means of the instruction which the game affords’.17 Kreigsspiel and the rule variants made to it, was introduced to the US Army Service School at Fort Leavenworth by an instructor who translated previous rules and publications.

The development of Kreigsspiel in the 1800s demonstrated the utility of games in learning tactics through the effective command of fire and movement, and the management of time and tempo. While the original game was focused on land forces, the use of games for tactics was also important for naval warfare. Simon Parkin’s book, A Game of Birds and Wolves tells the story of one discrete example in the naval context of how war games can assist in understanding adversary tactics and the development of counter-tactics. The book focuses on the work of the Western Approaches Tactical Unit (WATU) to understand the tactics of German U-Boats and enable escort ships to protect the convoys traversing the Atlantic Ocean. WATU consisted of members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WREN) and led by Commander Gilbert Roberts, Royal Navy.

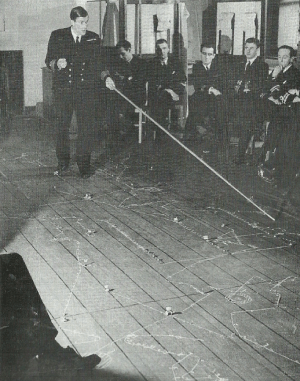

Figure 2 – Captain Roberts talking through actions in ‘The Game’. Image from General Staff.

WATU used the floor of their HQ in Portsmouth as a giant board for a game that simulated wolfpack attacks on Atlantic convoys (figure 2). The games were based on intelligence and battle reports to understand how convoy escort commanders behaved and if they could do anything different to avert any losses.18 Through the use of such games, WATU eventually discovered the U-boat wolfpack tactics and developed counter-attack measures they called ‘Raspberry’.19 The tactics developed by WATU were tested via war games and then implemented for convoy operations in the Atlantic via the Western Approaches Convoy Instruction.20 WATU also conducted ‘The Game’ (as it was simply called) for officers about to deploy to the Atlantic. According to Parkin, between February 1942 and July 1945, the WATU conducted 130 tactical courses that involved approximately 5000 naval officers playing ‘The Game’ they developed. Further, many of the course graduates highlight the importance of the games they played as being instrumental to how they fought their battles against the U-boats.21

The focus of both Kreigsspiel and ‘The Game’ are on tactics. Modern war games such as Flames of War (15 mm miniatures / company level) and Bolt Action (28mm miniatures / platoon level) use World War II armies and historical settings as the foundation for war gaming company or platoon level tactics in a table top war game. Warlord Games, which produces Bolt Action, has also produced aerial combat / strike and naval warfare themed war games, Blood Red Skies and Victory at Sea. These game systems are also focused on re-creating World War II major aerial and naval engagements respectively. These games assist in PME by providing insight into the tactics employed and challenges faced by commanders during some important battles, and also enhance an understanding of key battles of World War II. However, the scale of the games and focus on tactical engagements can limit the learning outcomes, particularly for PME courses that are intended to focus on operational and strategic level considerations.

A number of computer games such as Squad and Arma III are similarly focused and can also be used to enhance education in combined arms and tactics. ‘Squad’ is focused on developing collaborative approaches and communication via VOIP and dedicated command channels in a massive online combined arms warfare environment. ‘Arma III’ is a first person military simulation in a sandbox environment, which is not focused on particular game objectives but provides an environment for experimentation and free-play. The primary benefit of computer games such as these over the tabletop war games is that they offer access to a multiplayer collaborative environment involving a multitude of real players across the Internet.

More complex operational level games with historical themes are also available but are complex and long. The educational benefits of such games may be diluted by the time that needs to be invested in learning the rules for a particular campaign in history. As noted by Lt. H. Chamberlain, who invented a game called Naval Blockade in the late 1800s, a rule of thumb is that the number of people who can be persuaded to play a game will vary inversely as the square of its difficulty!22 However, complex games that can be tied in to courses on grand strategy, for example, should be incorporated into PME where possible. The recent RAND table top game, Hedgemony, is focused on assisting Defence professionals with how to use different strategic approaches that arise from the need to make choices about the prioritisation of finite resources within time constraints. The educational value of games such as ‘Hedgemony’ are to teach Defence planners how the selection of different strategic approaches impact on force posture, force design, resource management, and options for use of military forces. These are all valuable lessons for Defence personnel at the higher levels of JPME.

War games have also been used as a means of testing concepts and plans and have a central role in education and training related to military planning processes. Conducting a war game as a means of assessing a course of action developed in the Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) is central to the Course of Action Analysis step in the process. One historical example is the use of wargaming by the Imperial Japanese Navy Combined Fleet HQ conducted war games over four days to test the operational plans for operations at Midway in 1942. The majority of commanders and staff officers attended the tabletop wargame, which revealed the vulnerability of Japanese carriers to land based aircraft. Unfortunately, in this case, the Fleet Chief of Staff – Rear Admiral Ugaki – intervened with the umpire ruling to reduce the number of Japanese carriers struck and invalidated the wargame. The detrimental effect for the IJN is that the original results of the war game had accurately predicted the Japanese defeat at Midway through the destruction of significant parts of its carrier force.23

The IJN example highlights the need for war games conducted for testing and simulation to be executed with an open mindset that is focused on the lessons that can be revealed by the war gaming process. The inculcation of this open mindset, confidence in the war game process, and willingness to learn lessons can be shaped by regular exposure games and play as a learning and development opportunity as part of the PME. A paper by Yuna Huh Wong from RAND also provides some guidelines, including highlighting key limitations, of using war games for testing plans and theories.24 She makes the following key points to guide the use of war games for testing concepts:

- A game is a model, and all models are abstractions from reality.

- There can be considerable conscious and subconscious pressure to give wargame sponsors the outcomes that they want or largely expect.

- Games can also help by disproving your theory.

- A game can also help test your theory by bringing attention to things that previously did not come to mind.

- Wargames also provide a chance to consider alternate conceptualizations of the problem.

War games have naturally focused on the actions of belligerents in a conflict. Game developer – Awaken Realms – have taken a different perspective on the ‘war game’ and created This War of Mine in 2017. The game is centred on the civilian experience of war. It is a collaborative boardgame for 1-6 players with a focus on the survival of the civilians in a fictitious war torn and besieged city. Players have to scavenge for food, find shelter, avoid snipers, and fight against other hostile survivors. Players often have to make significant life or death decisions that have moral consequences in a bid to survive.

The developers designed the game based on their ‘belief that a board game can be as effective a medium as movies or books to allow others to experience something important’. Their aim was to use the game to highlight the human experience of war from a civilian perspective, and as a reminder that real war is not entertainment or a ‘fun’ game but has significant and tangible human costs.25 This War of Mine has also been released as a video game, with a number of expansions including one called This War of Mine: The Little Ones which is focused on the experience of survival in a war zone from a child’s perspective. Civilians are largely ignored in war games, but their presence in the battlespace is a major strategic issue that impacts directly on the planning and conduct of military operations. This game’s contribution to PME is to provide a different perspective to conflict, and to provide insight into the significant challenges faced by the civilian population in a war zone. While a game such provides only limited insight into the civilian experience of survival, it provides military personnel with a unique perspective that they are not likely to have considered at all.

Conflict and competition through abstraction

While war games have a direct relationship with military PME, there are several other games that can enhance PME through the abstract themes and concepts that they present by focusing on conflict and competition from a non-military lens. These themes and concepts include grand strategy, resource management, and force design.

Grand strategy and resource management. Sid Meier’s Civilization VI involves players building ‘civilizations’ from the Stone Age through to the Information Age, with set victory conditions that can be seen through the lens of different aspects of national power. One example of a victory condition is ‘Science Victory’ which involves being the first civilization to launch a satellite, land on the moon, and establish a Martian colony. The challenge is to manage the grand strategy of your empire – resources, scientific research, military forces, and diplomatic and trade relationships – as a means to achieving one of the set victory conditions. The game requires players to make decisions and trade offs regarding their investment in certain sectors of their civilization, depending on their planned victory condition. Degradation in trade relationships through bad negotiations, or the commencement of hostilities against other civilizations can result in the re-direction of time and national resources to the restoration of important diplomatic relationships or the conduct of war. The game is a useful simulation that highlights the challenges of pursuing a grand strategy.

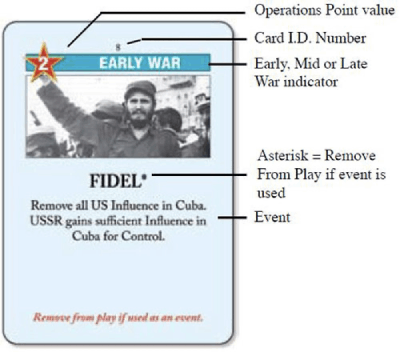

Twilight Struggle by GMT Games is 2-player (USSR vs US) Cold War themed strategy game that highlights the pitfall of pursuing global domination without access to enough resources. The game is designed to create the tension between the Cold War hegemons and highlights the necessary trade off in resources that is required when deciding between a number of strategic options towards the victory points necessary for success within a limited number of rounds. Each card played has a cost and an event. As part of playing a card during a turn, the player must choose between using the points resources provided by that card (card value) or the event on the card – which may benefit you or your opponent. As an example, the card in figure 3 may be required by the US player for its points value to increase the US influence in Europe, at the cost of activating the event on the card in favour of the Soviet player in another theatre (South America).

Figure 3- Example of Twilight Struggle Card (from UltraBoardGames.com)

The value of Twilight Struggle to PME are the lessons it provides in the challenges of apportioning resources and effort in pursuit of a strategy that is likely to change over the course of the game as part of managing both the consequences of prior strategic decisions and the inevitable responses of the adversary.

Force design. Released in 1993, the collectible card game, Magic: The Gathering (MTG) involves two or more players who play as wizards – using artefacts, casting spells, and summoning creatures in battle. Players must create a deck of 60 cards from a possible pool of 20,000 cards, with hundreds of cards added annually.26 The card mechanics involve colours, the mana system, and card type. The colours are associated with particular strategies, mechanics and philosophies, and have been placed on a colour wheel to show their meaning and association (see figure 4). Mana is the resource for playing spells, with different spells having varying mana costs. This forces players to make important choices about how they manage the mana cards in their limited deck, to ensure they have enough resources to cast spells. The card types – artefact, creature, enchantment, instant, land, etc – determine how they are played.27

Figure 4 – Magic: The Gathering Colour Wheel (© Wizards of the Coast)

Players must build their deck of 60 cards with no knowledge of the cards in their opponent’s deck. Players must determine a strategy that considers the power and synergy between their cards, and being able to counter the cards that their opponent may have. Generally, players focus on a set of colours to include in the deck, which increases the probability of drawing those cards during play, but at the expense of limiting the number of tactical options available.28 MTG is about designing your force in a manner that maximises its fighting power through card combinations, within your limited resource pool, but yet remain flexible enough to face an unknown opponent. At its simplest, and armed with some knowledge of the lore of MTG and the universe around it, this card game can provide elementary insights into the problem of force design.

Conclusion

This post was intended to provide an overview of how games can enhance PME. War games have a long history in achieving this – using games for teaching tactics and operational planning, and the testing of operational concepts. Recently, games have also been used to provide insight to different experiences of war, such as the civilian experience that the gameplay of This War of Mine provides. Outside of military or war games, a broader range physical and online games can also provide lessons in abstract.

The challenge is in ensuring that the right games are matched with the learning outcomes of PME, and this will vary by course and learning level under the Australian JPME continuum. Games can contribute to the education and training by introducing and developing different ways of thinking about problems, developing judgement and decision-making in an environment of resource scarcity, enhancing an empathetic approach to conflict by providing an alternative view of war, and by providing a safe environment to test plans and concepts. Military and civilian educational institutions – such as the Georgetown Wargaming Society, the Naval War College Wargaming Department, and McGill University – have incorporated (war)games into their programs or have dedicated departments and groups focused on using games for education. The value of games to PME is the development of skills and attitude necessary to succeed in the perpetual environment of conflict and competition. This is perhaps best summarised by Christopher Lewin in War Games and Their History29

The qualities needed to play all strategic war games well include forethought, the ability to make a plan and execute it, avoidance of the temptation to over-reach oneself when experiencing an advantage, and the courage to face unexpected adverse developments calmly and with resolution. These are some of the same qualities which are required of real-life leaders, not just in military jobs but as statesmen and as the managers of large companies.

The Australian Defence College must examine how to incorporate games into courses at various levels of the Australian JPME continuum to enhance the development of these essential traits in the military and national security leaders that the college educates.

Group Captain Jo Brick is a Legal Officer in the Royal Australian Air Force and she is currently the Chief of Staff at the Australian Defence College. She has served on several operational and joint staff appointments throughout the Australian Defence Force. Group Captain Brick is a graduate of the Australian Command and Staff Course. She holds a Master of International Security Studies (Deakin University), a Master of Laws (Australian National University) and a Master (Advanced) of Military and Defence Studies (Honours) (Australian National University). She is a Member of the Military Writers Guild, an Associate Editor for The Strategy Bridge, and an Editor for The Central Blue.

1 Ken Robinson (with Lou Aronica). Creative Schools (Great Britain: Penguin UK, 2015), 94.

2 Simon Parkin. A Game of Birds and Wolves – The Secret Game that Won the War (Great Britain: Sceptre, 2019), 41.

3 Major-General Mick Ryan. An Australian Intellectual Edge for Conflict and Competition in the 21st Century. The Centre of Gravity Series – Strategic & Defence Studies Centre ANU College of Asia and the Pacific – March 2019, 3

4 Ryan, Australian Intellectual Edge, 3.

5 Ryan, Australian Intellectual Edge, 5-9.

6 See also William H. Starbuck and Jane Webster. ‘When Is Play Productive?’ (1991). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2708169 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2708169. A comprehensive discussion of the taxonomy of serious games and edutainment can be found in Johannes Breuer and Gary Bente. Why so serious? On the relation of serious games and learning. Journal for Computer Game Culture, 2010, 4 (1), pp.7-24. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal- 00692052.

7 Sara de Freitas and Fotis Liarokapis ‘Serious Games: A New Paradigm for Education?’ in Ma M., Oikonomou A., Jain L. (eds) Serious Games and Edutainment Applications (London: Springer, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-2161-9_2

8 The Australian JPME levels are: Learning Level 1 – Professional foundation (ab initio to first appointment course O2 / APS 2-4; Learning Level 2 – Tactical Mastery (O2 – junior O4 / APS 4-6); Learning Level 3 – Operational Art (mid O4 – mid O5 / APS 6-EL1); Learning Level 4 – Nascent Strategist (senior O5-O6 / EL1-EL2); Learning Level 5 – National Security Leadership (O7+ / SES 1+).

9 Cited by Lewin, War Games, 2012; 40.

10 A detailed study of the history of wargames can be found in Matthew B. Caffrey, Jr., "On Wargaming" (2019). The Newport Papers. 43 https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/newport-papers/43

11 Lewin, War Games; 41-42.

12 Lewin, War Games, 43.

13 Lewin, War Games, 45.

14 Lewin, War Games, 43-44.

15 Lewin, War Games, 44.

16 Lewin, War Games, 44.

17 Lewin, War Games, 45.

18 Parkin. A Game of Birds and Wolves, 143.

19 Parkin. A Game of Birds and Wolves, 161.

20 Parkin. A Game of Birds and Wolves, 168.

21 Parkin. A Game of Birds and Wolves, 264.

22 Lewin, War Games, 57.

23 Brigadier P. Young and Lieutenant-Colonel JP Lawford. Charge! Or How to Play War Games (London: Morgan-Grampian, 1967) 7.

24 Yuna Huh Wong, ‘How Can Gaming Help Test your Theory?’ The RAND Blog, 18 May 2016.

25 Michal Oracz, Jakub Wisniewski (authors) and Marcin Swierkot (Awaken Realms) letter to Kickstarter backers of This War of Mine board game (2017).

26 Magic: The Gathering Wiki (accessed 24 October 2020).

27 Magic: The Gathering Wiki (accessed 24 October 2020). For more information on the basic aspects of MTG, see Darren Orf, ‘How to Play “Magic: The Gathering”: Everything You Need to Know’, Popular Mechanics online, 11 August 2020 (accessed 20 October 2020).

28 Magic: The Gathering Wiki (accessed 24 October 2020).

29 Lewin, War Games, 9.

Comments

Start the conversation by sharing your thoughts! Please login to comment. If you don't yet have an account registration is quick and easy.